1. Introduction

Polymyxin B (colistin) has been used in agriculture and veterinary medicine since the 1960s. The recent discovery of the plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance gene mcr-1 in China (1) has grabbed the attention of medical science. Colistin is the last available drug to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria, particularly carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (2). Since 2015, more than 10 distinct alleles of mcr-1 have been reported in Escherichia coli (E. coli), Klebsiella, and Salmonella globally (3). The incidence and spread of the plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance gene mcr-1 in E. coli pose a global concern to the community. Of our particular concern is the dissemination of mcr-1 into carbapenemase-producing or extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs)-producing E. coli, which results in highly resistant strains, e.g., pandrug-resistant strains that are potentially untreatable (4). Reports are still infrequent on E. coli isolates co-harboring mcr-1 and blaNDM-1 from clinical cases. We report the first case of E. coli pandemic clone sequence type 648 co-harboring colistin-resistance-encoding mcr-1, carbapenemase-encoding blaNDM-1, and ESBLs-encoding blaCTX-M-15 from a clinical case in Shenzhen, China.

2. Method

An 83-year-old male presented to the Medicine Department of Shenzhen hospital with the main complaint of diarrhea in 2015. Initially, Enterobacter species from fecal samples were cultivated on a Columbia blood agar plate. The acquired bacteria were routinely subjected to biochemical tests as well as API 20 system (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) with and further confirmed by using 16S rDNA PCR and sequences. Extended-spectrum -lactamases production was confirmed using the combination disc diffusion method and carbapenemase production was confirmed using a carbapenem inactivation method (CIM), followed by antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed with 22 routinely used antimicrobial agents using the VITEK2 compact system (Ref. No. 27530/275660) according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute guidelines (CLSI guidelines, 2010).

The standard PCR method was performed to detect the presence of ESBLs-producing genes; blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaGES, and blaVEB using specific primers as previously described. Additionally, carbapenemase genes (blaKPC and blaNDM-1) and colistin-resistance mcr-1 were determined in ESBL-producing E. coli by the PCR assay and sequencing. The specific primers were used as described in our previous study (Table 1). The purified PCR products were sequenced commercially (Sangon Biotech-Shanghai, China). DNA sequences were analyzed by the NCBI-BLAST program. Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) was determined by amplifying the internal portions of seven housekeeping genes of E. coli (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA) with specific primers as described in the E. coli MLST database (http://mlst.ucc.ie/mlst/dbs/Ecoli). The phylogenetic group was determined by multiplex PCR assays, using a combination of three DNA marker genes (chuA, yjaA, and TspE4.C2) as described by Clermont et al. (2000).

| Resistance Genes | Primer Pair Sequences | Amplicon Size, bp | Annealing Temperature, ºC |

|---|---|---|---|

| mcr-1 | ATGATGCAGCATACTTCTGTG | 1626 | 56 |

| TCAGCGGATGAATGCGGTG | |||

| blaNDM | TGCGGGGTTTTTAATGCTG | 785 | 53 |

| TGGCTCATCACGATCATGC | |||

| blaKPC | ATGTCACTGTATCGCCGTC | 883 | 54 |

| TTACTGCCCGTTAACGCC | |||

| blaTEM | AGGAAGAGTATGATTCAACA | 531 | 57 |

| CTCGTCGTTTGGTATGGC | |||

| blaSHV | GGTTATGCGTTATATTCGCC | 866 | 57 |

| TTAGCTTTGCCAGTGCTC | |||

| blaOXA48 | TTGGTGGCATCGATTATCGG | 745 | 55 |

| GAGCACTTCTTTTGTGATGGC | |||

| blaSME | AACGGCTTCATTTTTGTTTAG | 831 | 55 |

| GCTTCCGCAATAGTTTTATCA | |||

| blaCMY | CTGACAGCCTCTTTCTCCA | 504 | 56 |

| GCCAAACAGACCAATGCT | |||

| blaVIM | GTTAAAAGTTATTAGTAGTTTATTG | 799 | 60 |

| CTACTCGGCGACTGAGC | |||

| blaIMP | ATGAGCAAGTTATCTGTATTC | 741 | 60 |

| TTAGTTGCTTGGTTTTGATGG | |||

| blaGES | ATGCGCTTCATTCACGCAC | 864 | 57 |

| CTATTTGTCCGTGCTCAGG | |||

| blaCARB | AAAGCAGATCTTGTGACCTATTC | 588 | 56 |

| TCAGCGCGACTGTGATGTATAAAC | |||

| blaPER | AGTCAGCGGCTTAGATA | 978 | 56 |

| CGTATGAAAAGGACAATC | |||

| blaVEB | GCGGTAATTTAACCAGA | 961 | 57 |

| GCCTATGAGCCAGTGTT | |||

| blaCTX-M | TTTGCGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA | 544 | 57 |

| CGATATCGTTGGTGGTGCCATA |

Primers Used in This Study

Conjugation experiments were performed to analyze the horizontal gene transfer of blaCTX-M, blaNDM-1, and mcr-1 using streptomycin-resistant E. coli C600 as the recipient strain. We used the liquid mating assay as described in our earlier study. Transconjugants were selected on Luria Bertani agar containing streptomycin 2000 (μg/mL) and cefotaxime (32 μg/mL). The transconjugants were further tested by the PCR assay, followed by sequencing. PCR-based replicon typing was performed to detect the plasmid type using 18 pairs of primers that are recognized as Inc (incompatibility) replicon types: FIA, FIB, FIC, HI1, HI2, I1-Ic, L/M, N, P, W, T, A/C, K, B/O, X, Y, F, and FIIA. Moreover, IncX typing was determined as reported by Timothy J. et al. (2007).

3. Results and Discussion

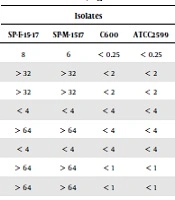

We confirmed the E. coli SP-17 isolate in the stool sample of a diarrhea patient by biochemical tests. The API 20 system (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) further confirmed 16S rDNA sequences. The antibiotic susceptibility test results showed that the E. coli SP-17 isolate was most resistant to colistin [minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) = 8 mg/mL)], followed by ampicillin, ceftazidime, cefepime, aztreonam, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, doxycycline, minocycline, ceftriaxone, gentamicin, nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim, and ertapenem but sensitive to piperacillin, cefotetan, imipenem, amikacin, and tigecycline (Table 2). Escherichia coli SP17 showed a pandrug-resistant phenotype known as “superbug”. Based on the PCR assay and sequencing, we confirmed E. coli SP 17 co-harboring mcr-1, blaNDM-1, and blaCTX-M-15. In addition, blaSHV, blaTEM, blaaac, mphA, strA, and dfrA were detected in the same isolate. We did not find other β-lactamase genes including blaGES and blaVEB. The housekeeping gene sequences and phylogenetic group analysis showed that the E. coli SP17 isolate belonged to the ST648 type group A (Table 3).

| Antibiotics | Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations, mg/L | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolates | ||||

| SP-E-15-17 | SP-M-1517 | C600 | ATCC2599 | |

| Colistin | 8 | 6 | < 0.25 | < 0.25 |

| Ampicillin | > 32 | > 32 | < 2 | < 2 |

| Ampicillin Sulbactam | > 32 | > 32 | < 2 | < 2 |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | < 4 | < 4 | < 4 | < 4 |

| Cefazolin | > 64 | > 64 | < 4 | < 4 |

| Cefotetan | < 4 | < 4 | < 4 | < 4 |

| Ceftazidime | > 64 | > 64 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Ceftriaxone | > 64 | > 64 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Cefepime | 16 | 8 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Aztreonam | > 64 | > 64 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Ertapenem | < 0.5 | < 0.5 | < 0.5 | < 0.5 |

| Imipenem | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Tobramycin | 8 | < 4 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Amikacin | < 2 | < 2 | < 2 | < 2 |

| Gentamicin | > 16 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | > 4 | < 0.5 | < 0.25 | < 0.25 |

| Levofloxacin | > 8 | < .05 | < 0.25 | < 0.25 |

| Nitrofurantoin | < 16 | < 16 | < 16 | < 16 |

| Trimethoprim | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 |

| Doxycycline | > 16 | < 4 | < 4 | < 4 |

| Minocycline | > 16 | < 4 | < 4 | < 4 |

| Tigecycline | < 0.5 | < 0.5 | < 0.5 | < 0.05 |

Antibiotic Susceptibility of Escherichia coli Strain SP-15-17 and Its Transconjugants

| Isolate | Housekeeping Genes | ST | STCLPX | Phylogenic Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adk | fumc | gyrb | icd | mdh | purA | recA | ||||

| SP-E-15-17 | 92 | 4 | 87 | 96 | 70 | 58 | 2 | ST648 | ST648 | A |

Details of MLST and Phylogenetic Analysis

Carbapenem and colistin-resistant C600 transconjugants were successfully obtained from this isolate. The PCR-based replicon type assay showed that plasmids carrying mcr-1 and blaNDM-1 belonged to IncX3, the size of which was confirmed in 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis. The co-existence of blaNDM-1 and mcr-1 has been reported in the specimen of cases with bloodstream infection and urinary tract infection (5). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study from Shenzen, China, that reports such an occurrence in the fecal specimen of a colonized individual. The MLST and phylogenic group results showed that the E. coli SP17 isolate belonged to ST648 type group A, which is the most pandemic clone combining multidrug resistance and virulence (6). The E. coli ST648 clone has been observed globally in humans, companion animals, livestock, and wild birds and is commonly allied with various β-lactamases, including ESBLs, NDM, and KPC (7, 8).

Conjugation experiments showed that the plasmids harboring the mcr-1 and blaNDM-1 genes were successfully transferred to E. coli EC600, indicating that mcr-1 and blaNDM-1 were located on conjugative plasmids but blaCTX-M-15 was located on another plasmid. Similar results have been reported globally. The PCR-based replicon typing indicated that the resistance determinants were located on the commonly reported IncX3 plasmid. One limitation of this study is the lack of performing S1-PFGE, followed by Southern blotting to determine the location of the gene or even the whole genome sequencing.

4. Conclusions

Overall, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of co-harboring mcr-1 and blaNDM-1, and blaCTX-M-15 in E. coli ST648 isolated from a diarrhea patient in Shenzhen, China. The occurrence of the multidrug-resistance enzyme-encoding genes in E. coli ST648 (group A) pandemic clone is quite alarming to society. The constant surveillance of the field strains is essentially required.