1. Background

Listeria monocytogenes is an intracellular parasitic zoonotic pathogen causing listeriosis in animals and humans (namely neonates, pregnant women, and immune-compromised individuals) (1, 2). Listeria monocytogenes has a strong environmental adaptability and can survive at high temperatures and in acidic high-salt (3, 4) and other unfavorable stressful environments and consequently form a biofilm. Recently, many studies have shown that the adaptability of L. monocytogenes to the stressful environment is closely related to its complex regulatory network, in which PrfA (5) and SigmaB (6-8) play an important role in regulating the stress adaptability and virulence of L. monocytogenes.

As an important food-borne pathogen, L. monocytogenes can infect host cells under the mediation of various pathogenic factors. Until now, many pathogenic factors, including InlA, InlB, ActA, InlC, LLO and phospholipase (PlcA, PlcB) (9-13), have been extensively studied. It is proved that the expression of these virulence factors was regulated by PrfA, sigmaB, and other transcription regulatory factors, resulting in the long-term intracellular survival and proliferation of L. monocytogenes (1, 14). Listeria monocytogenes can cross the hosts’ blood-brain, blood-fetal, and gastrointestinal barrier (15), thereby posing significant problems in the food industry.

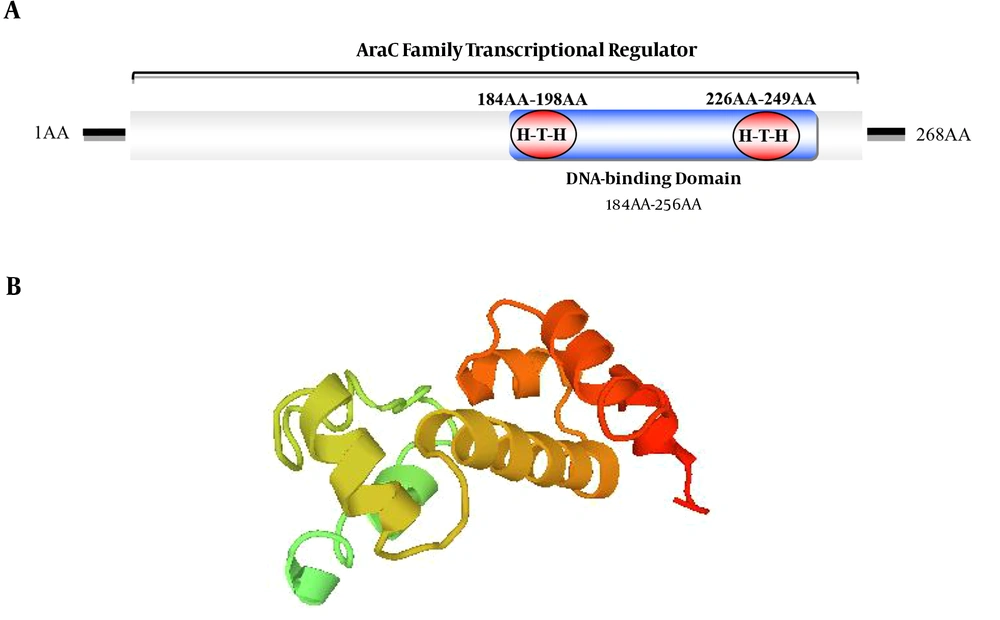

Many studies have confirmed the significance of transcriptional regulation for L. monocytogenes in adapting to different environments (5, 16), including the AraC family, which could exert its functions in both Gram-positive and negative bacteria (17-21). Structurally, the AraC family members contain a conserved helical-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain (22), which can activate gene transcription and play regulatory roles in adapting to environmental stresses and virulence (18, 19, 21, 23). lmo2672, a novel AraC family regulator, is encoded by the differential gene lmo2672 between virulent and avirulent strains of L. monocytogenes (24). However, the biological function of lmo2672 is still unclear.

2. Objectives

The main purpose of this study was to explore the potential roles of lmo2672 in adverse environment adaptation, biofilm formation, and motility of L. monocytogenes. To this end, we constructed a lmo2672 deletion L. monocytogenes strain (LM-Δlmo2672) and compared its adaptability to adverse environmental stresses, biofilm formation, and motility with its parental strain L. monocytogenes EGD-e to provide insights into the lmo2672 mechanism in transcriptional regulation of L. monocytogenes.

3. Methods

3.1. Strains and Plasmids

The L. monocytogenes EGD-e strain was a gift from Professor W. Goebel at the University of Wurzburg, Germany. The strain was cultured in brain heart infusion broth (BHI) (Sangon, China). Escherichia coli DH5α was preserved by the College of Animal Science and Technology at Shihezi University (Shihezi, China) and cultured in LB media (Difco, USA). The temperature-sensitive plasmid pKSV7 was provided by Professor Zhu Guoqiang from Yangzhou University (Yangzhou, China).

3.2. Primers

The primers used for constructing L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 and primers for qRT-PCR analysis of genes associated with environmental adaptation and flagellar movement were designed based on the genome sequence of L. monocytogenes EGD-e in GenBank (accession number: AL591824.1) using Primer software version 5.0 (Premier Biosoft International, USA). The 5’ ends of F1 and R2 primers were flanked with Kpn I and Pst I (Takara, Japan) sites and protective bases, respectively (Table 1).

| Primer Names | Nucleotide Sequence (5’ → 3’) | Size of Amplicons, bp |

|---|---|---|

| lmo2672F | ATGGCTAAGCTAGAAACGTT | 807 |

| lmo2672R | TCATTGTATATTTGCGACATTT | |

| F1 | GGGGTACC CTGTCATTTTTTCTCCTCCT | 638 |

| R1 | CAAAGCATTTACGTTTTAAAGAGACCCCCTTTTC | |

| F2 | GAAAAGGGGGTCTCTTTAAAACGTAAATGCTTTG | 698 |

| R2 | AACTGCAG GCGAATCAAGTCTTTATCTC | |

| F3 | ATAACGTCGCAAGGTGCATG | 2309/1502 |

| R3 | GGTCCATACAGAAAACCACGA | |

| F4 | ATGATTAATGAATTTGTTTGTA | 840 |

| R4 | TTAGAGTTTTTCGACAGTCT | |

| prfA-F | TTAGCGAGAACGGGACCAT | 392 |

| prfA-R | TGCGATACCGCTTGAATAG | |

| sigB-F | TCATCGGTGTCACGGAAGAA | 310 |

| sigB-R | TGACGTTGGATTCTAGACAC | |

| motA-F | TGGAAGAACGTCATGCTGCT | 129 |

| motA-R | GTTCGACATTTCGCCCATCG | |

| motB-F | AATCGCCAAAGAAATCGGCG | 130 |

| motB-R | GGCGACACTTAGTTCCCAGT | |

| fliP-F | TGAATGTGCATGCCGAGAGT | 82 |

| fliP-R | ACAAACAGCGCCACACTAGA | |

| fliE-F | ACCGCGAAAACAGACAATGC | 96 |

| fliE-R | TACGGAAGTTTGCGCGTTTG | |

| flhA-F | ATGAACTCCTGATGCGCCAA | 129 |

| flhA-R | GTTGTCGTAGCACCCCTTGA | |

| 16S rRNA-F | GATGCATAGCCGACCTGAGA | 116 |

| 16S rRNA-R | TGCTCCGTCAGACTTTCGTC | |

| rpoB-F | TGCCATTTATGCCAGAC | 188 |

| rpoB-R | TTCTTCCACTGTGCTCC |

3.3. Cloning and Molecular Characterization of lmo2672 Gene

In brief, lmo2672 gene was amplified using L. monocytogenes EGD-e genomic DNA as a template and the lmo2672F-lmo2672R primers. After gel purification, the product was ligated with pMD19-T simple vector (TaKaRa, Japan) overnight and transformed into E. coli DH5α strain. The positive clones were selected by sequencing. Its encoded protein was analyzed using Expasy software (http://www.expasy.org/tools/) for it’s functional domains.

3.4. Construction and Identification of Listeria monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 Strain

The temperature sensitive plasmid pKSV7 was used to generate mutations, and LM-Δlmo2672 strain was then constructed by overlap extension (SOE) PCR and homologous recombination techniques. In brief, the upstream and downstream homologous arms of the lmo2672 were amplified using primer pair F1-R1 as well as primer pair F2-R2, respectively. The PCR products were then gel purified and subjected to the overlap extension PCR using primer pair F1-R2 to generate the lmo2672 deletion fragment (Δlmo2672). The fragment was then ligated with pMD19-T simple vector (TaKaRa, Japan) to obtain pMD19-T-Δlmo2672 and subcloned into pKSV7 after Kpn I and Pst I digestion. The obtained pKSV7-Δlmo2672 was then transformed into L. monocytogenes competent cells via electroporation to generate recombinant LM-Δlmo2672 strain. The LM-Δlmo2672 was then screened and serially passaged at 42°C in a chloramphenicol-containing BHI agar medium (Sangon, China). The selected LM-Δlmo2672 strain was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing and further cultured at 37°C in a chloramphenicol-free BHI medium.

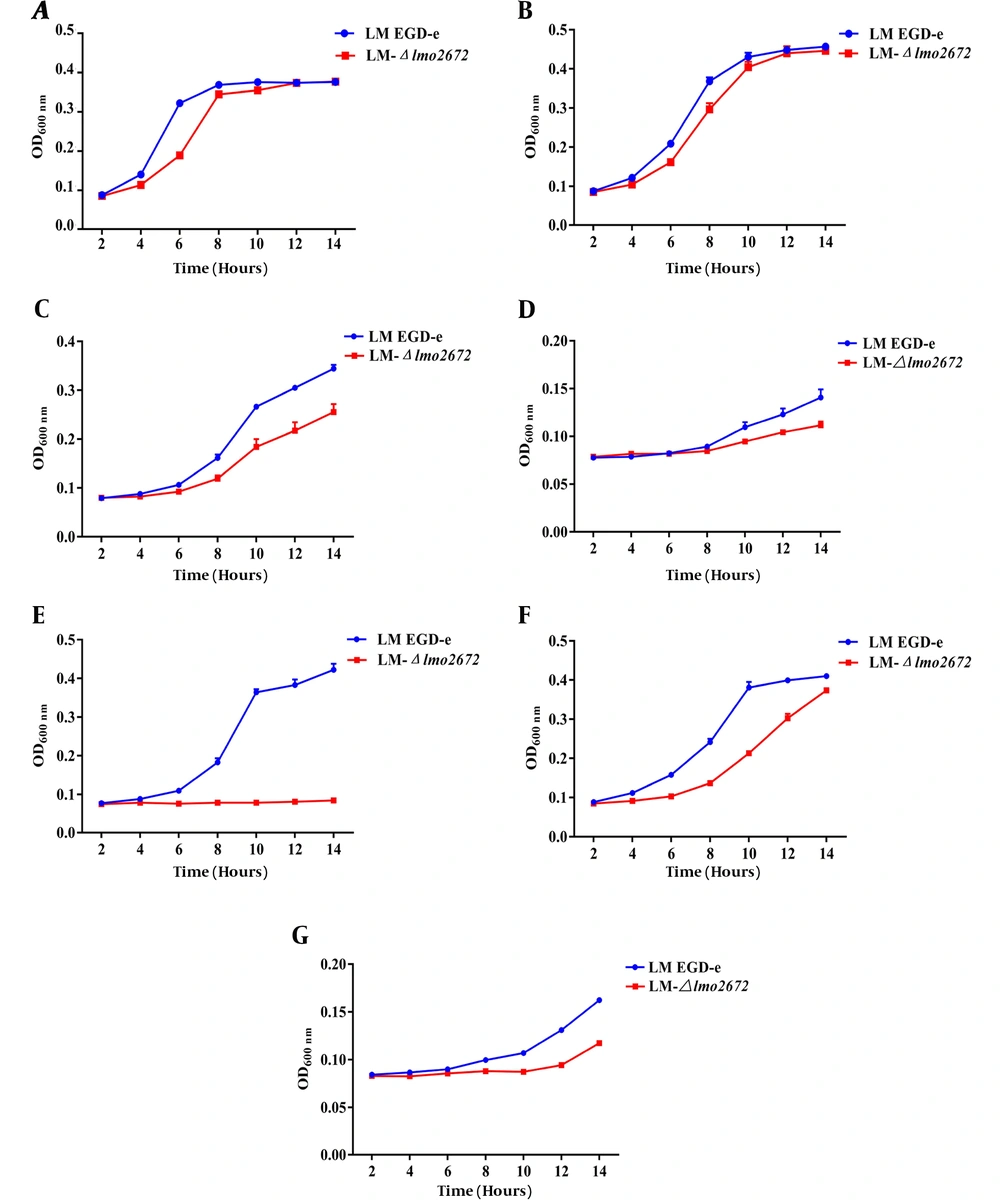

3.5. Effect of lmo2672 Gene Deletion on the Adaptability of Listeria monocytogenes to Environmental Stresses

Briefly, L. monocytogenes EGD-e and LM-Δlmo2672 single colonies were picked and cultured overnight at 37°C. After adjusting OD600 nm to 0.5, 50 µL of the cultures were inoculated into 5 mL of the fresh BHI medium and incubated at different temperatures (37°C and 42°C) or in BHI media containing different osmotic pressures (5% NaCl, 8% NaCl), 0.3% bile salts, 5 mM H2O2, 1% Triton X-100, respectively. The growth curve of these stains was plotted after measuring OD600 values every 2 h. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the adaptability of L. monocytogenes EGD-e and LM-Δlmo2672 to stressful environments was then analyzed, as previously reported (25).

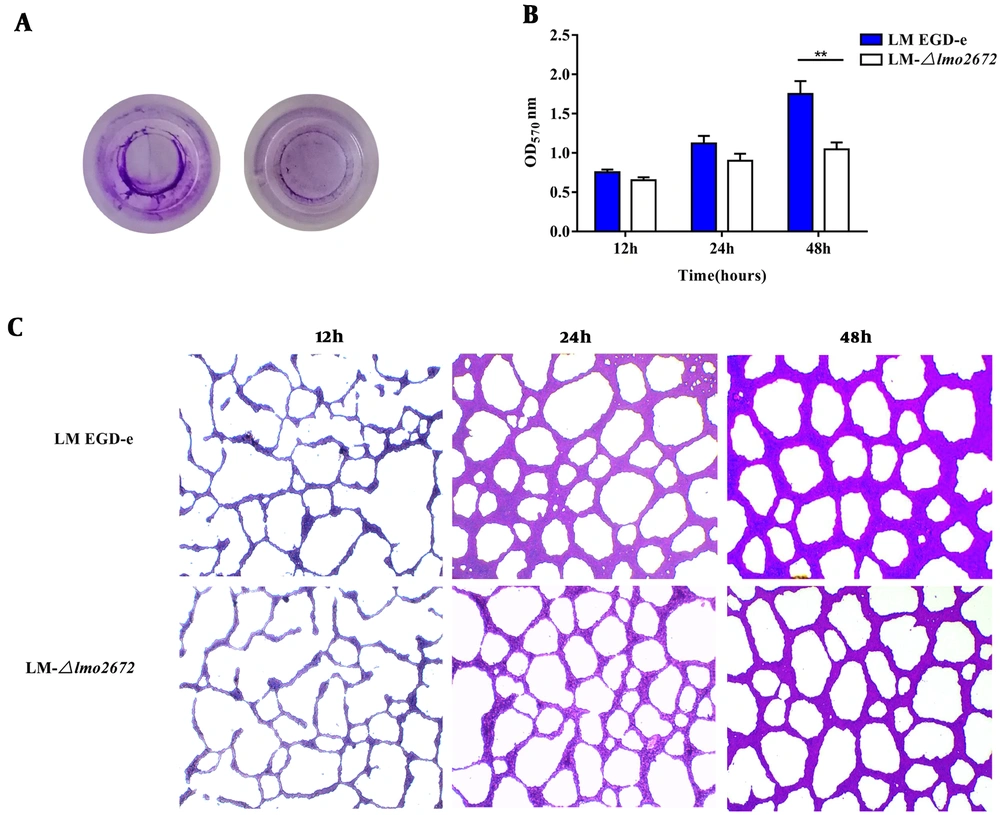

3.6. Effects of lmo2672 Gene Deletion on Biofilm Formation Ability of Listeria monocytogenes

The biofilm formation ability of L. monocytogenes was determined using the microplate method. In brief, the overnight cultures of L. monocytogenes EGD-e and LM-Δlmo2672 were diluted using the fresh BHI medium (Sangon, China) to OD600 nm = 0.2, and 200 μL of the diluted culture was inoculated into each well of a 96-well plate. After incubation at 37°C for 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h, respectively, the plate was washed with sterile water to remove the floating bacteria and dried for 45 min. Afterward, 150 µL of 1% crystal violet solution was added into each well and incubated the plate for 30 min. The Biofilm formation was observed under an inverted microscope (LEICA, Germany) and determined, as described by Peng (26). Each experiment was performed three times, with five replicates. The data were expressed as mean ± standard error.

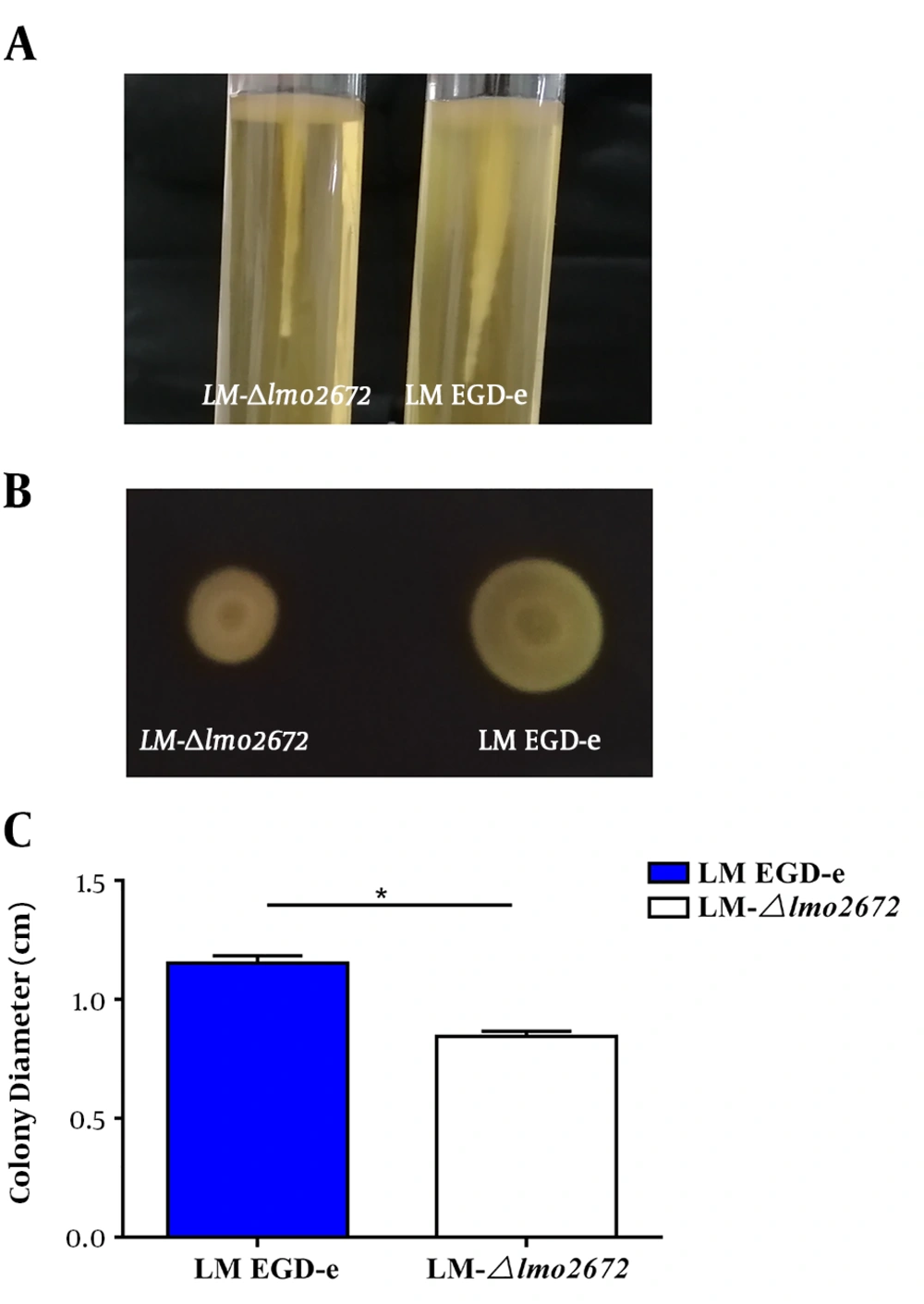

3.7. Effect of lmo2672 Gene Deletion on the Motility of Listeria monocytogenes

In brief, the single colonies of L. monocytogenes EGD-e and LM-Δlmo2672 were cultured overnight in the BHI medium at 28°C. After being adjusted to the same OD600 nm, 1 µL of the cultures were inoculated on the soft BHI agar plate (0.3%). Moreover, a small portion of the cultures were inoculated onto the 0.3% soft agar tube using an inoculation needle and cultured at 28°C for 48 h. The spots formed by the migration of the bacteria on the plate were photographed, and their diameters were measured. Each experiment was repeated three times. The data were expressed as mean ± standard error.

3.8. Determining Transcriptional Levels of Genes Associated with Stressful Environment Adaptability and Flagellar Formation of Listeria monocytogenes

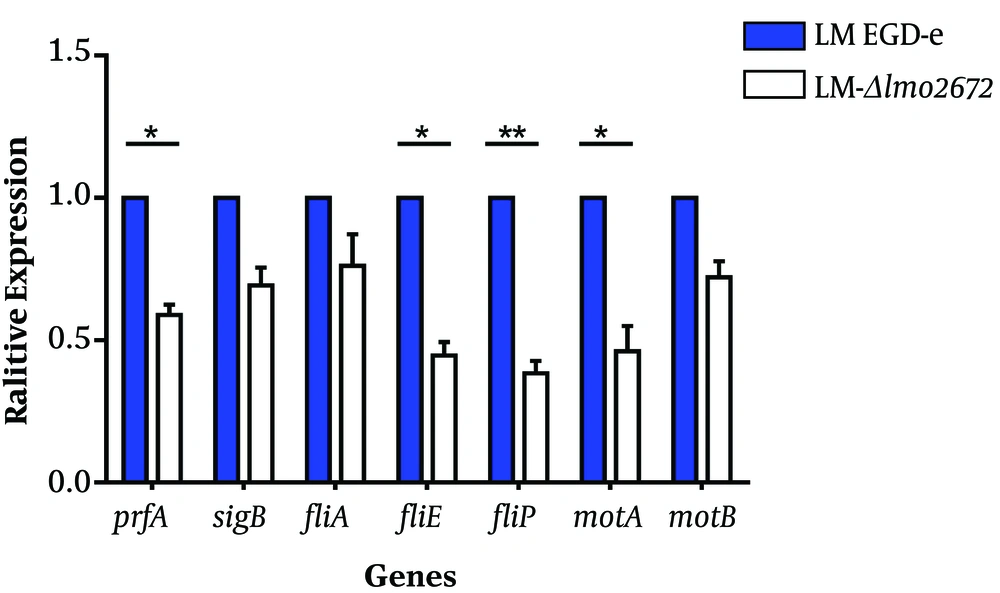

After being cultured at 28°C to OD600 nm ≈ 0.6, the cell pellets of L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 and L. monocytogenes EGD-e strains were collected by centrifugation and used to extract total RNA using Trizol (Invitrogen, USA) following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The cDNA was synthesized using an AMV reverse transcription kit (TaKaRa, Japan) following the procedure provided by the manufacturer. The synthesized cDNA was included as a template for qRT-PCR on the LightCycler 480 (Roche, Switzerland) instrument using the SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM kit (TaKaRa, Japan) to detect the transcriptional levels of two genes associated with environmental stress regulation (namely prfA and sigmaB) and five genes associated with flagellate (namely motA, motB, flhA, flip, and fliE). The relative transcriptional levels of the above genes were calculated according to the 2-ΔΔCT method using two housekeeping genes rpoB as the internal controls. Each experiment was repeated three times. The data were expressed as mean ± standard error.

3.9. Data Analysis

The differences between the L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 and L. monocytogenes EGD-e strains were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

The lmo2672 gene is 807 bp in length and encodes 268 amino acid residues (Appendix 1A in Supplementary File). Domain analysis revealed that the C-terminus of the lmo2672 had a typical helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain (Figure 1A). Tertiary structures predication revealed that the lmo2672 protein consisted of five α-helices, six β-sheets, four β-turns, and random coils (Figure 1B). The amplification performed by the primers F3-R3 showed a 1502 bp in L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 strain (Appendix 1B in Supplementary File). Further amplification by the primers F4-R4 and sequencing the amplified product indicated that the L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 strain was successfully constructed (Appendix S2 in Supplementary File).

The growth of L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 strain at 37°C and 42°C was significantly slower than that of the L. monocytogenes EGD-e strain (P < 0.05) (Figure 2A and B), indicating that the adaptability of L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 to temperature significantly decreased. Compared with the L. monocytogenes EGD-e strain, the L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 strain grew significantly slower in the medium with 5% NaCl (P < 0.05) and in the medium with 8% NaCl after 10 h (P < 0.05) (Figure 2C and D). The L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 strain did not grow in the BHI medium with 5 mM H2O2, showing significantly slower growth when compared with L. monocytogenes EGD-e strain (P < 0.01) (Figure 2E). Furthermore, compared with the L. monocytogenes EGD-e strain, the L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 strain also grew slower in the BHI medium with 1% Triton X-100 during 6 - 12 h (P < 0.05) and with 0.3% bile salts during 8 h (P < 0.01) (Figure 2F and G).

All the results indicated that the lmo2672 plays an important role in the adaptation of L. monocytogenes to environment stress The biofilm formation ability of the LM-Δlmo2672 strain at 12 h and 24 h culturing in BHI medium was not significantly different from that of L. monocytogenes EGD-e (P > 0.05); however, it was significantly weaker to form biofilm at 48 h than that of L. monocytogenes EGD-e (P < 0.01) (Figure 3). Testing the soft agar tube showed that the LM-Δlmo2672 significantly reduced motility, in comparison to the L. monocytogenes EGD-e (Figure 4A), and testing the soft agar plate also showed that spots formed by the LM-Δlmo2672 were significantly smaller than those formed by the L. monocytogenes EGD-e (P < 0.05) (Figure 4B), suggesting that the motility of LM-Δlmo2672 was remarkably reduced.

The qRT-PCR analysis showed that, compared to the L. monocytogenes EGD-e, the transcriptional levels of two genes associated with the environmental stress regulation and five genes associated with flagellar formation decreased to some extents in the LM-Δlmo2672, among which the transcriptional levels of prfA, motA, fliP and fliE decreased more significantly (P < 0.05) (Figure 5).

Effects of lmo2672 gene deletion on biofilm formation of LM. A, Biofilm on plates stained with crystal violet of LM at 48 h; B, biofilm of LM EGD-e and LM-Δlmo2672 biofilm determined by OD570 at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h, respectively; C, formation of biofilm by LM EGD-e and LM-Δlmo2672 at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h, respectively. Bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SE). **, indicates P values < 0.01.

5. Discussion

In this study, we successfully constructed the lmo2672 gene deletion strain L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 using the homologous recombination technology and compared its growth with its parental strain L. monocytogenes EGD-e in different stress environments. The results showed that the L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 grew significantly slower than the L. monocytogenes EGD-e at different temperatures and under osmotic pressures in the media containing 0.3% bile salts, 5 mM H2O2, or 1% Triton X-100. These results suggest that the lmo2672, a member of AraC transcriptional regulator family, plays an important role in the adaptation of the L. monocytogenes to adverse stressful environments.

Many studies have revealed that the AraC family is an important class of regulators in bacteria and encompasses more than 800 members, most of which are transcriptional activators involved in bacterial growth (20, 22, 27). In E. coli, SoxS expression is upregulated in response to oxidative stress (28), while OpiA and Robcould enhance the bile acid tolerance (29, 30). However, the lack of axyR, an AraC family regulator, does not affect the adaptation of L. monocytogenes to temperature and acid or osmotic stress conditions (31).

Due to strong environmental adaptability, the L. monocytogenes could survive under stressful conditions such as food processing, storage, and transportation (14, 32). However, the regulation mechanism of the L. monocytogenes in response to stressful environments is not fully understood yet. The existing studies have confirmed that the environmental adaptability of L. monocytogenes is regulated by multiple factors such as PrfA and sigmaB (5, 7, 16, 33). In this study, the transcriptional levels of PrfA and sigmaB in the L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 strain decreased, suggesting that the lmo2672 may exert its regulatory role in stressful environments by regulating the expression of PrfA and sigmaB. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism of the lmo2672 regulating PrfA and sigmaB genes needs to be further studied.

It is reported that the AraC family members mediate the transcriptional regulation of the genes associated with the biofilm formation in bacteria. Top et al. (34) showed that the deletion of EbrB, an AraC family regulator, decreased the biofilm formation ability of Enterococcus faecalis. Rowe et al. (19) showed that Rbf promoted the biofilm formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis by regulating the expression of icaADBC. Moreover, Camargo et al. (35) confirmed that SptRSSs, the other AraC family regulator, was involved in the biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans. Our results showed that the biofilm formation ability of the LM-Δlmo2672 was significantly lower than that of the L. monocytogenes EGD-e, indicating that the lmo2672 contributes to the formation of the L. monocytogenes biofilm.

Flagellum is not only a movement organ of bacteria, mediating the propagation of bacteria in the hosts, but also plays an important role in adhesion to the cell surface (36). Studies have revealed that the loss of AraC family member significantly reduced the survival of bacteria and its pathogenicity (17). Gode-Potratz et al. (37) concluded that ExsA, an AraC family transcriptional regulator, could affect the expression of the flagellin gene flgBL in Parasporal vibrio. Our findings confirmed that the L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672 strain significantly decreased motility. Moreover, the expressions of the motA, flip, and fliE significantly decreased in the LM-Δlmo2672, in comparison to L. monocytogenes EGD-e, suggesting that lmo2672 played a regulatory role in the transcription of these three genes.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, we successfully established a lmo2672 deletion L. monocytogenes strain, L. monocytogenes-Δlmo2672, and confirmed that lmo2672, a member of AraC family, plays important regulatory roles in environmental stress adaptability, biofilm formation and motility of L. monocytogenes. These findings in the present study provided new insights into the regulatory mechanism of lmo2672 in L. monocytogenes.