1. Background

Staphylococci are common Gram-positive bacteria that inhabit community and hospital settings. Among all staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus is the most notorious coagulase-positive Staphylococcus sp. and causes severe clinical infections and food poisoning (1, 2). In addition, the heterogeneous group of coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) has become increasingly prevalent, and CoNS are listed as major nosocomial opportunistic pathogens (3). Antimicrobial resistance is a global issue. Due to increasing resistance, community-isolated staphylococci may become a severe threat to public health, with delayed treatment opportunities and higher costs. Oxacillin and cefoxitin are commonly used to treat staphylococcal infections. Expression of the mecA gene, which encodes the low-affinity penicillin-binding protein, PBP-2a (4), was reported to be the main reason that staphylococci show resistance to oxacillin and cefoxitin. Thus, mecA gene expression inhibits treatment of clinical infections (5). Typing the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec), the mobile genetic element carrying mecA, can provide a detailed genetic linkage of mecA (6).

Reports on staphylococcal virulence have mainly concentrated on staphylococci in food, but few reports have concentrated on staphylococci in community settings. Staphylococci can produce multiple toxins, including staphylococcal enterotoxin (SE), hemolysin (HL), and Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL). SEs damage the host immune system by targeting the innate and adaptive responses (7), and HL and PVL can damage cell membranes, causing severe diseases (8, 9). Increasing numbers of staphylococcal surveillance systems are being reported in community settings, such as metro systems (10), hotels (11), washrooms (12), and other non-healthcare settings (13), but few staphylococcal surveillance systems have been reported on densely populated campuses. Chenggong University Town in Kunming city in Southwestern China was built in 2010.

Ten universities and colleges have entered this university town and accommodate more than one hundred thousand students. The high population density provides ideal conditions for staphylococcal transmission via hand-touching surfaces. If the staphylococci on these surfaces contain virulence and drug-resistance genes, these bacteria could threaten community public health. Therefore, understanding the molecular characteristics, microbiology and epidemiology of the staphylococci isolated from hand-touching surfaces in this university town is crucial.

2. Objectives

In this study, we surveyed the epidemiology, antimicrobial resistance and virulence of staphylococci isolated from hand-touching surfaces in Chenggong University Town in Southwestern China.

3. Methods

3.1. Strain Collection and Identification

Samples were collected from hand-touching surfaces from six universities in Chenggong University Town from March 2016 to May 2016. The high-frequency hand-touching surfaces were predetermined to include stair rails, elevator buttons, campus card transfer machines, automated teller machines, door handles, classroom desks, library entrance machines, and refrigerator handles in convenience stores. The swab sampling method was followed as previously described (10). Each swab was placed in a sterile tube with 5 mL saline to dilute the bacterial concentration, then transferred to Luria-Bertani agar plates and incubated for 18 - 24 hours. Single clones were selected and incubated with Luria-Bertani broth for another 24 hours. Genomic DNA was obtained using a TIANamp Bacterial DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Genealogical classifications of the 16S rRNA were determined for each strain via PCR amplification and 27F/1492R primer sequencing (27F: 5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’, 1492R: 5’-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’). The sequences were blasted in the NCBI database for species identification. Nonduplicated colonies identified as Staphylococcus were selected.

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed on all collected staphylococci using the VITEK-2 compact (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). The antimicrobial tests included the primary test, which reported resistance to erythromycin, clindamycin, oxacillin, benzylpenicillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and tests for resistance to other routinely reported antimicrobials, including gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, quinupristin-dalfopristin, linezolid, vancomycin, tetracycline, tetracycline, nitrofurantoin, and rifampicin. In addition, the VITEK-2 compact provided the cefoxitin screening test for detecting methicillin-resistant strains mediated by mecA. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing interpretive standard followed the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute, M100S 27th.

3.3. Resistance Gene Detection and mecA Typing

The mecA gene was detected and identified in all staphylococcal strains via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. For the mecA-harboring strains, multiplex PCR was used to type the SCCmec, and mecA was classified as types I - V or nontypeable as previous report (6). Table 1 lists the primers used for the PCR. We further surveyed the multilocus sequence typing of S. aureus by amplifying and sequencing seven housekeeping genes (https://pubmlst.org/saureus/). The anti-disinfectant-related gene, qac, was also detected.

| Primers | Primer Sequences(5’-3’) | Base Pairs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| mecA gene | |||

| mecA-F | GTTGTAGTTGTCGGGTTT | 437 | (14) |

| mecA-R | CCACATTGTTTCGGTCTA | ||

| Anti-disinfectant | |||

| qac-F | CAGTTTGTAATTGGAGGC | 429 | (14) |

| qac-R | TTTCTTTGATAGCTGCTTG | ||

| Exotoxins | |||

| seA-F | TTGGAAACGGTTAAAACGAA | 120 | (15) |

| seA-R | GAACCTTCCCATCAAAAACA | ||

| seB-F | TCGCATCAAACTGACAAACG | 478 | (15) |

| seB-R | GCGGTACTCTATAAGTGCC | ||

| seE-F | AGGTTTTTTCACAGGTCATCC | 209 | (15) |

| seE-R | CTTTTTTTTCTTCGGTCAATC | ||

| seG-F | AAGTAGACATTTTTGGCGTTCC | 287 | (15) |

| seG-R | AGAACCATCAAACTCGTATAGC | ||

| seH-F | GTCTATATGGAGGTACAACACT | 213 | (15) |

| seH-R | GACCTTTACTTATTTCGCTGTC | ||

| seI-F | GGTGATATTGGTGTAGGTAAC | 454 | (15) |

| seI-R | ATCCATATTCTTTGCCTTTACCAG | ||

| seU-F | AAACATTAAAGCCCAAGAG | 241 | This study |

| seU-R | ACCGCCATACATACACG | ||

| Hemolysin | |||

| hlA-F | ATGGTGAATCAAAATTGGGG | 205 | (16) |

| hlA-R | GTTGTTTGGATGCTTTTC | ||

| hlB-F | GCCAAAGCCGAATCTAAG | 241 | (16) |

| hlB-R | CGAGTACAGGTGTTTGGT | ||

| hlG-F | CTCTTGCCAATCCGTTATTA | 253 | (16) |

| hlG-R | GCTTTAACATGATTAGTTTT | ||

| hlD-F | TGACAGTGAGGAGAGTGGTGT | 254 | This study |

| hlD-R | GTGCACCATGTGCATGTCTT | ||

| Panton-Valentine leukocidin | |||

| pvl-F | ACACACTATGGCAATAGTTA TTT | 176 | (17) |

| pvl-R | AAAGCAATGCAATTGATGTA | ||

| Coagulase | |||

| cal-F | GAGATACAGACAATCCACATAA | 601 | (18) |

| cal-R | CTACCTTCAAGACCTTCTAAAA |

The Primer Used for Detection of Resistance and Virulence Genes

3.4. Virulence Gene Checking

The CoNS isolates were confirmed by verifying the coagulase gene, cal. Common toxin-producing genes were also detected in all staphylococcal strains, including staphylococcal enterotoxin genes (seA, seB, seE, seG, seH, seI, and seU), staphylococcal hemolysin genes (HLa, HLb, HLd, and HLg), and the Panton-Valentine leukocidin gene (pvl). Table 1 lists the primers used to verify the virulence genes.

4. Results

4.1. Isolation of Staphylococci

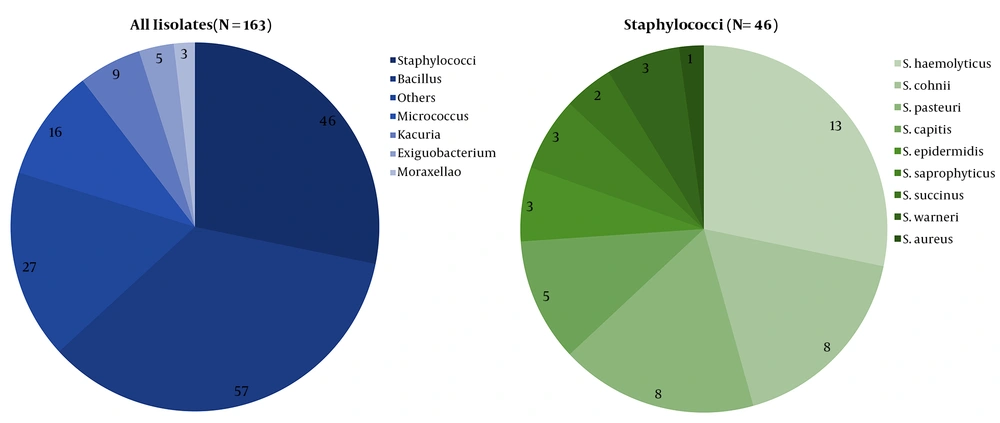

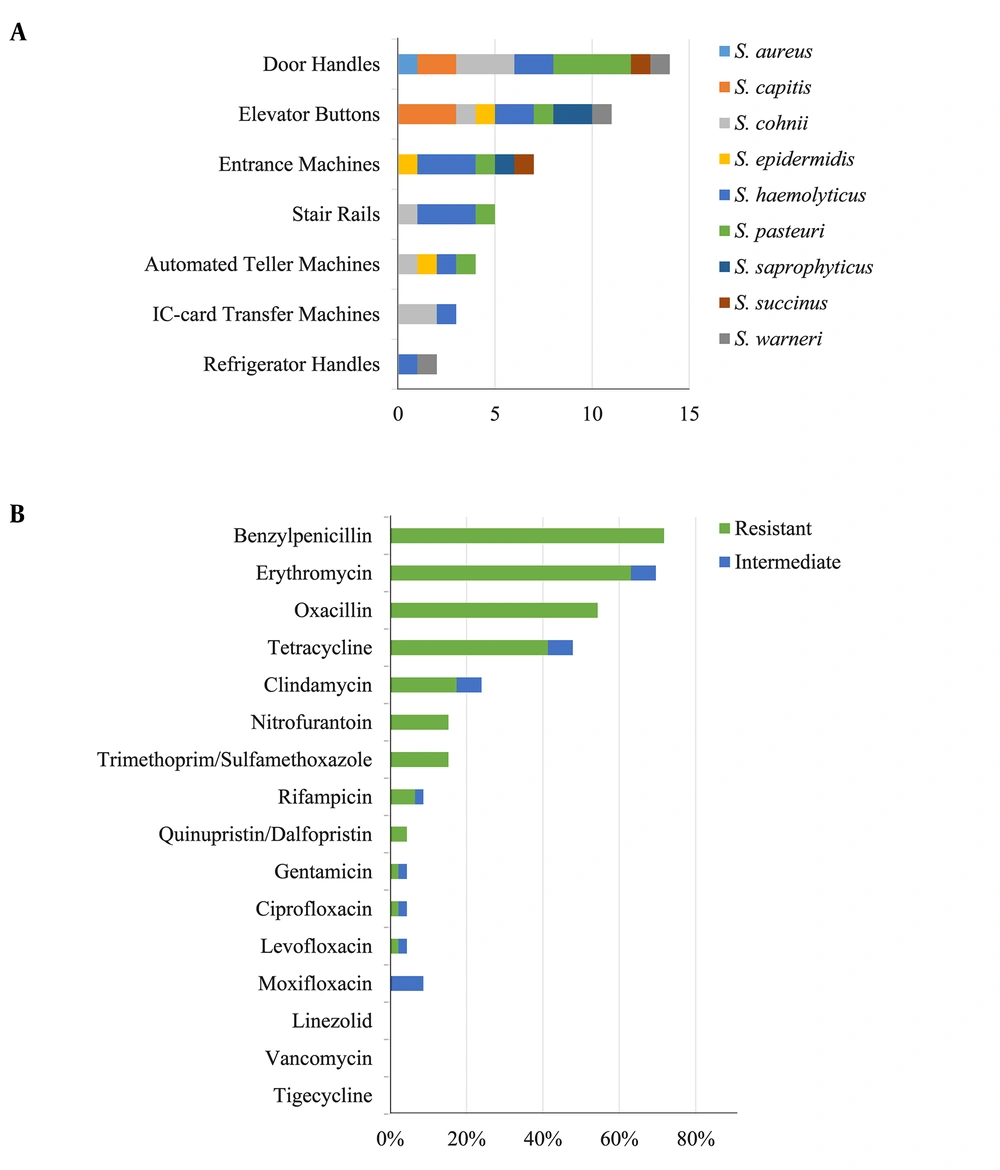

From March 2016 to May 2016, 163 strains belonging to diverse genera, including Bacillus, Micrococci, and Kocuria, were collected and identified. Among them, 46 strains (28.22%) were identified as staphylococci, and nine distinct species were detected according to the genealogical classification results of the 16S rRNA sequencing: S. aureus (1/46, 2.17%), S. capitis (5/46, 10.87%), S. cohnii (8/46, 17.39%), S. epidermidis (3/46, 6.52%), S. haemolyticus (13/46, 28.26%), S. pasteuri (8/46,17.39%), S. saprophyticus (3/46, 6.52%), S. succinus (2/46, 4.35%), and S. warneri (3/46, 6.52%) (Figure 1). All staphylococcal species were CoNS, except S. aureus. Figure 2A shows the predetermined seven locations from which the staphylococci were obtained.

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Sixteen antibiotics were used to test the antimicrobial susceptibility of the 46 collected staphylococcal strains. The 46 staphylococcal strains showed high resistance rates of over 40% to four commonly used antimicrobials (benzyl-penicillin, erythromycin, oxacillin and tetracycline) and resistance rates of less than 20% to clindamycin, nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, rifampicin, quinupristin-dalfopristin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin (Figure 2B). None of the strains showed resistance to linezolid, vancomycin or tigecycline. Strains that displayed resistance to at least three antimicrobial classes were categorized as multidrug-resistant (MDR). Of the 46 staphylococci, 41.30% (19/46) were MDR. The S. aureus strain was identified as MDR and showed resistance to benzyl-penicillin, oxacillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, and tetracycline.

4.3. Molecular Epidemiological Characteristics of Resistance Genes

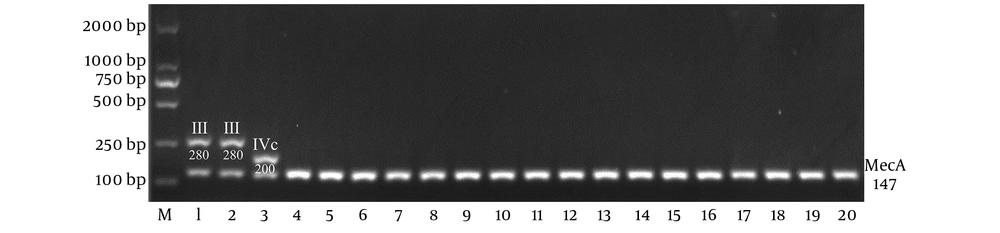

Table 2 shows the mecA and qac detection rates. Of the 25 oxacillin-resistant staphylococci, 20 isolates carried mecA and tested positive for cefoxitin resistance, but the other 5 isolated oxacillin-resistant staphylococci did not. Among the mecA carriers, 60.00% (12/20) were categorized as MDR. SCCmec typing showed that two mecA carriers were SCCmec type III, one was SCCmec type IVc, and the remaining seventeen were nontypeable (Figure 3). The nontypeable SCCmec staphylococci showed a wide species distribution and varying minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs; 0.125 to ≥ 4 μg/mL) to beta-lactams (Table 3). In addition, 22 strains carried the anti-disinfectant-related gene, qac. The oxacillin-resistant S. aureus strain carrying the qac and mecA (type IVc) genes was considered methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), and further multilocus sequence typing showed that this strain was ST59.

| Class | Gene | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance | mecA | 20 | 43.48 |

| qac | 23 | 50.00 | |

| Virulence | seA | 5 | 10.87 |

| seB | 3 | 6.52 | |

| seE | 0 | 0.00 | |

| seG | 0 | 0.00 | |

| seI | 3 | 6.52 | |

| seH | 1 | 2.17 | |

| seU | 0 | 0.00 | |

| hlA | 12 | 26.09 | |

| hlB | 6 | 13.04 | |

| hlD | 8 | 17.39 | |

| hlG | 16 | 34.78 | |

| pvl | 3 | 6.52 | |

| cal | 1 | 2.17 |

The Carry Rates of Resistance and Virulence Genes

| Species | SCCmec | No. of Isolates | MIC Range (μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzylpenicillin | Oxacillin | |||

| S. aureus | IVc | 1 | ≥ 0.5 | 0.5 |

| S. capitis | Nontypeable | 3 | ≥ 0.5 | 0.5 ~ ≥ 4 |

| S. cohnii | Nontypeable | 4 | 0.125 ~ ≥ 0.5 | 0.5 ~ 1 |

| S. epidermidis | III | 1 | ≥ 0.5 | 0.5 |

| S. haemolyticus | Nontypeable | 3 | 0.25 ~ ≥ 0.5 | 0.25 ~ 0.5 |

| S. haemolyticus | III | 1 | ≥ 0.5 | 0.5 |

| S. pasteuri | Nontypeable | 3 | ≥ 0.5 | 0.5 ~ ≥ 4 |

| S. saprophyticus | Nontypeable | 2 | 0.125 ~ 0.25 | 0.5 ~ 2 |

| S. succinus | Nontypeable | 1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. warneri | Nontypeable | 1 | ≥ 0.5 | ≥ 4 |

SCCmec Types and MIC Ranges Among mecA Carrying Staphylococci

4.4. Molecular Epidemiology of the Virulence Genes

Virulence gene detection revealed that 28 strains (28/46) harbored at least one virulence gene. Seven strains carried only staphylococcal enterotoxin genes, 15 strains carried only hemolysin genes, and one strain carried only pvl. Moreover, three strains carried both se and hl but not pvl, and one strain carried pvl and se but not hl. The S. aureus strain carried seB, hlA, hlB, hlD, hlG and pvl in addition to cal, but no CoNS strains carried cal. Table 2 shows that hlG (16/46) was the most frequently detected virulence gene, followed by hlA (12/46), hlD (8/46), hlB (6/46), seA (5/46), seB (3/46), seI (3/46), pvl (3/46) and she (1/46), while seE, seG and seU were undetected.

5. Discussion

Staphylococci are common widespread Gram-positive bacteria that are reported to be a significant threat for nosocomial infections because of their drug resistance and an important food-safety threat because of their virulence. In the current study, we surveyed the prevalence of staphylococci isolated from hand-touching surfaces in the new Chennggong University Town and further characterized the epidemiology of staphylococcal resistance and virulence.

The selected sampling sites were in public locations and could be touched by random people. We cultivated the samples using Luria-Bertani (L-B) agar plates, which can be used to incubate and culture most bacteria, including common opportunistic pathogens. The samples were diluted and transferred to L-B agar plates, which enabled determining the staphylococcal proportions in the L-B-culturable environmental samples. We acquired more than twenty bacterial species that were common in the environment, and, other than the staphylococci, most isolates showed no or few harmful effects to humans. Forty-six staphylococcal isolates, followed by the most easily-isolated Bacillus spp. (57/163, 34.97%), accounted for more than a quarter of all isolates (46/163, 28.22%), implying that staphylococci commonly adhere to hand-touching surfaces around the university.

Door handles, elevator buttons and entrance machines were the top 3 locations from which staphylococci were collected (Figure 2A). These locations all had metal surfaces, suggesting that staphylococci adhere more easily to metal surfaces than do other bacterial species. In addition, few S. aureus isolates were obtained in this study; however, as previous studies reported, S. aureus is more easily isolated from food (isolated rates of 17.7%) (19), and food (especially meat) may provide better growth conditions for S. aureus (20, 21). In addition, insects such as cockroaches may serve as media for bacterial transmission (22). However, in this study, the hand-touching surfaces lacked sufficient nutritional conditions, which might be more suitable for community-related staphylococcal adherence.

Drug-resistant bacteria are receiving increasing attention in clinical infection control because of their adverse effects, including delayed healing and higher treatment costs (23). In this study, 33 isolates (71.74%) were resistant to benzyl-penicillin, 29 (63.04%) to erythromycin, 25 (54.35%) to oxacillin, and 19 (41.30%) to tetracycline. These were the four highest resistance rates, and all were over 40%. A previous study (14) also found that community-acquired Staphylococcus had higher resistance rates to oxacillin (27.90%), G-penicillin (26.74%), and erythromycin (22.09%) than to other antibiotics, but these rates were lower than those found in the present study. Additionally, 19 strains (41.30%) showed characteristics of multidrug resistance, which was similar to the results of a previous report (49.6%) (24), but was higher than that found for food-source strains (20.73%) (25).

The high resistance rates to commonly used antibiotics and the existence of MDR strains suggest an increasing threat to public health due to community-acquired Staphylococcus in this university town. Nevertheless, the resistance rates of these community-acquired strains to commonly used drugs were lower than those of clinical strains (26). Furthermore, no strains showed resistance to linezolid, vancomycin or tigecycline, which are considered the final effective agents for controlling staphylococcal infections. Therefore, although resistance to community-acquired staphylococci threatens public health, strategies against staphylococcal infections are available.

The mecA gene is important for conferring staphylococcal resistance to beta-lactam antimicrobials. Eleven SCCmec types have been reported for S. aureus, but some reports have shown that CoNS harbor a greater variety of SCCmec genes, enabling various mecA genes to be exchanged between S. aureus and CoNS strains (27). Among the mecA-harboring CoNS strains, except for one SCCmec type III strain and one SCCmec type IVc strain, 17 mecA genes could not be classified via current approaches, suggesting that environmental staphylococci may have greater SCCmec diversity than that of clinical isolates. In addition to carrying mecA, multiple other mechanisms can lead to oxacillin resistance, and 5 non-mecA-harboring strains have shown oxacillin resistance due to other mechanisms, such as biofilm formation, which has been previously described (28).

More than half the staphylococcal strains (28/46) carried at least one virulence gene, and hemolysin genes were the most prevalent (20/28), suggesting that these community-acquired staphylococci can easily cause infections. Of these strains, 26.09% (12/46) carried staphylococcal enterotoxin genes, whereas a larger number of food-source strains (20/24) carried these genes (15). Nearly half the toxin-producing staphylococcal strains (13/28) harbored mecA, suggesting that these antibiotic-resistant strains, together with toxic strains, are potential burdens to public health, and the hand-touching surfaces from which they were isolated should be sterilized. However, the qac gene was prevalent in more than half (7/13) of the mecA and virulence gene-harboring strains, and another 16 strains carried the qac gene; thus, various disinfection methods should be considered.

In this study, CoNS were the most easily isolated pathogenic bacteria. Other than the CoNS, pathogenic bacteria were detected at low rates in this university town. Only one Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain and one S. aureus strain were detected among the 163 collected strains, and these two species are considered opportunistic pathogens commonly detected in clinical settings. Although only one S. aureus strain was isolated, further analysis revealed that this strain was a threat to public health. Multilocus sequence typing showed that this classroom-isolated strain was ST59, which is mostly isolated from clinical settings but less often from environmental settings as described in the database, and it once caused severe pneumonia in China (29).

In the current study, strain ST59 was identified as MRSA via antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and this strain was carrying type IVc mecA. As previously described (30), ST59 can harbor multiple SCCmec types such as IV, V, VII and VIII. CoNS strains isolated from the same place may carry many SCCmec types, which may enable exchanging mecA with S. aureus ST59. Furthermore, the seB, hlA, hlB, hlD, hlG and pvl virulence genes were detected, which conferred infection and food-poisoning abilities to this MRSA strain. Multiple virulence factors and multidrug resistance, together with harboring the qac gene, enable ST59 to easily invade the human body and be difficult to disinfect.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus is commonly scattered across hand-touching surfaces in Chenggong University Town. Virulence, antibiotic resistance and disinfectant resistance are prevalent among these staphylococci and can potentially threaten food safety, infection treatments and public health. To reduce the risk of infection by staphylococci, which adhere to and are transmitted on hand-touching surfaces, more effective disinfectant strategies are urgently needed, and feasible surveillance measures should be adopted.