1. Background

Pathotypes of Escherichia coli cause diseases in particular groups of patients with various complications. Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) is one of these pathotypes that has the ability to produce one or two Shiga toxins (1, 2). There are different serotypes of STEC, among them, enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) has received special attention because the resulted disease causes hemorrhagic colitis (HC), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), which are life-threatening (3). In general, people with immune deficiency, such as children and the elderly, are more sensitive to severe illness or death due to STEC infection. Although food is a major source of the infection, close contact with infected animals and humans could cause infection in sensitive individuals. Secretion of Shiga-like toxins (stx) after colonization of the bacterium in the intestine promotes intestinal and extra-intestinal damages (kidneys and central nervous system) (4, 5). Each type of Shiga toxin (Stx1 and Stx2), is composed of several variants on the basis of its sequence diversity (5, 6). These genes are located on lambdoid bacteriophages and their cooperation with other virulence factors, such as aggregative adhesin and intimin (eae), and enterohemolysin (ehxA), could induce more severe disease in infected patients (4).

Annually, it is estimated that STEC can cause 2,801,000 acute cases, 3890 HUS, 270 permanent end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and 230 deaths in the world. STEC, in spite of its low mortality rate, could cause severe complications mainly in the pediatric age group in both developed and less developed countries, which shows its prioritization for control programs among foodborne pathogens (7). Pathogenicity of STEC is cooperatively assisted by some virulence factors. Intimin, which is an adhesin encoded by eaeA gene located on a pathogenicity island called LEE (locus of enterocyte effacement), is produced by a lot of STEC. Intimin adheres STEC to the intestinal epithelial cells and causes attaching and effacing lesions in the intestinal mucosa. Another factor that may increase the effect of Shiga toxins and pathogenicity of STEC strains is enterohemolysin, which is encoded by the Exhly gene (8).

Owing to an incubation period of 3 - 4 days and the severity of symptoms, it is necessary to use rapid and reliable diagnostic methods for the detection of the responsible agent in stool samples of the patients. One of the diagnostic methods is cultivation and isolation, which is mainly designed for EHEC strains, but not all STEC serotypes. There is a need to characterize the suspected colonies using biochemical and serological tests due to diversity in biochemical reactions of EHEC variants (4). Confirmation of these tests must then be done serologically, which is a time consuming and expensive method (3). This limitation also exists for other tests, such as immunomagnetic separation of STEC from the enrichment culture using monoclonal antibodies against common STEC serotypes (that is costly and needs equipment), and latex agglutination test (that is costly and needs further analysis to detect the presence of factors such as eae) (4).

Nowadays, PCR-based methods were offered to reduce the cost of diagnosis, and decease of turnaround time for report of positive and negative samples (2). Although high specificity and shorter turnaround time of PCR have some benefits for the detection of STEC, it has some challenges, such as the existence of PCR inhibitors and common microbial flora in the stool samples. In cases with a low count of STEC (≤ 10 - 200 organisms/gram stool), due to the limitation in usage of small volumes of DNA extracts (1 - 10 µL) for PCR, there is a need to determine limit of its detection level for each reaction. Quality of DNA extracts can confer a significant effect on the sensitivity of the method (4). Accordingly, the application of molecular methods for detection of STEC in medical laboratories needs standards warranting the validity of the performance of tests.

Considering the costliness of molecular diagnostic methods and the necessity for their adaptation based on diversity in strains and the reagents, validation of laboratory results is one of the most important indicators for clinical application. In order to achieve this goal, it is necessary to evaluate designed assays and their results in a population of samples. To prevent false negative and positive results, providing positive and negative controls (internal or external) in these reactions is a need.

2. Objectives

In this study, to optimize PCR and real-time PCR methods for detection of STEC in stool samples, application of a chimeric vector containing characteristic genes of STEC (stx1, stx2, eae, EhxA) was assessed for usage as positive control in PCR and real-time PCR assays. Moreover, effect of stool inhibitors on the reactivity of PCR and real-time PCR assays, and repeatability, limit of detection (LOD), and the sensitivity of these tests were studied on the spiked samples with different concentration of STEC strains.

3. Methods

3.1. Bioinformatics-Based Study for Selection of Target Sequences for Constructing Plasmid Vector

Nucleotide sequences of the target genes stx1, stx2, eae, EhxA were obtained from GeneBank database and their diversity was determined by CLC sequence viewer software. Prediction of formation of hairpin loop and other structures interfering with PCR in the selected regions was determined by KineFold and RNA structure software, version 6.0. A chimeric sequence with optimum structural property related to stx1, stx2, eae, EhxA genes was designed. The sequence was ordered for synthesis and insertion in a commercial DNA cloning vector (GENEray Biotechnology Company).

3.2. Design and Construction of Primers for Gene Targets

Suitability of primer sequences for amplification of target genes was checked using primer blast server according to nucleotide sequences presented in GenBank database. Moreover, sequences of forward and reverse primers were analyzed for the optimum reaction properties, such as 3’ delta G, primer dimer, and melting temperatures.

3.3. Preparation and Cloning of the Chimeric Plasmid

To prepare the vector for cloning and application, TE buffer (Tris-EDTA buffer, pH = 8) was added to the vector lyophilized vial based on the manufacturer’s brochure to obtain 50 ng/µL plasmid concentration. This stock was maintained at -20°C and 1:100 working dilutions in TE buffer were used during the studies. E. coli DH5-α was used for cloning. For transformation, the competent cells were prepared in CaCl2 according to the protocols described by Seidman et al. (9), and Sambrook and Russell (10). In brief, a single colony of the standard strain of E. coli DH5-α on LB Agar (Luria-Bertani agar) was inoculated into 50 mL of LB broth (Luria-Bertani broth) and incubated at 37°C (18 hours) with an average shaking (250 rpm) in an orbital incubator overnight (18 h). Then, 4 mL of this culture was inoculated into 400 mL of Luria-Bertani broth and incubated at 37°C with an average shaking (250 rpm) until the OD590 reached to 0.375 (about 3.5 h). Finally, OD at 590 nm wavelength was measured by the UV/VIS spectrometer lambda 25 device. The competent cells were subjected to transformation by the amount of 1 µL of the chimeric plasmid stock (10 ng/µL of plasmid). Plasmid was then purified from transformed cells grown on a LB agar plate containing ampicillin by using the BIO BASIC kit (Canada). Concentration and quality of the extract were determined by NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo ScientificTM, USA).

3.4. Amplification of Target Genes in Plasmid Vector by PCR and Real-Time PCR Assays

To check the carriage of gene loci on the synthesized chimeric vector, the plasmid extract was subjected to PCR using the primers targeting the virulence genes. For this purpose, proper dilutions of the plasmid vector were analyzed by PCR. Amplification of stx1 and stx2 genes was done by both singleplex and multiplex assays. For real-time PCR, proper dilutions of the plasmid vector were tested by specific primers for stx1, stx2, eae, and EhxA. Melt curve analysis was performed to show the formation of nonspecific products. Different conditions were tested to find optimum programs of the amplifications. In order to evaluate the primers efficiencies, serial dilutions of plasmid stock (from 10-1 to 10-6 dilutions) were prepared and real-time PCR assays were performed. Concentration of each dilution was estimated and copy number of the plasmid was calculated according to the following formula:

Finally, the efficiency of the primers was evaluated by plotting the standard and linear curves using Rotor-Gene Q software.

3.5. Measurement of Limit of Detection (LOD) for Detection of Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli in Human Stool Samples by PCR and Real-Time PCR Assays

Limit of detection (LOD) was measured to determine the inhibitory effect of DNA extracts from human stool samples on the efficiency of the primers. The smallest copy number of the bacterium that the assay can detect was calculated based on the initial count of the inoculation after spiking the samples at a defined concentration (106 CFU). The dilutions provided 12 distinct concentrations of transformed E. coli DH5-α cells. DNA extract of E. coli O157:H7 (A positive control strain gifted by Reference E. coli Laboratory, Pasteur Institute of Iran) was used in all the experiments. Calculation of copy number of chromosomal DNA was performed after measurement of optical density (OD) of cultures using the following formula:

In this calculation, length of the chromosomal DNA was considered 47 × 105 bp. SinaClon’s DNA purification kit was used for preparation of DNA extracts from the spiked stool samples. All the experiments were done in two replicates.

3.6. Detection of the Sensitivity, True Positive, True Negative, and False Positive Results

Sensitivity of PCR method, i.e. its ability to detect true positive (TP) and true negative (TN) cases, based on the presence of different amounts of an analyte in a sample in comparison with the real-time PCR method, was determined in this study as described before (11). The formula for measurement of the sensitivity and efficiency are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively (12).

| Positive | Negative |

|---|---|

| A | B |

| C | D |

aTest positive; result negative.

bSensitivity: A/(A + C); false negative %: C/(A + C); false positive %: B/(B + D); positive predictive value: A/(A + B); negative predictive value: D/(C + D); % total agreement: (A + D)/(A + B + C + D).

3.7. Detection of the Repeatability of PCR and Real-Time PCR Assays

Repeatability that measures the lowest degree of variation is evaluated by conducting similar experiments on a number of repetitions under the same conditions. This measurement was done as described by Tawe (13) and Burd (14). In this calculation, STDAV, refers to standard deviation, cq refers to quantification cycle, and CV refers to coefficient of variation. The experiments were done in distinct time points. Each experiment was done in duplicate.

3.8. Evaluation of Chimeric Plasmid Vector for Usage as an Internal or External Control

To determine applicability of the chimeric vector for use as internal or external control in PCR and real-time PCR assays, 1:10th serial dilutions of DNA extracts from the standard strain (E. coli O157:H7, 10-1 to 10-6 dilutions) was prepared and used in combination with the chimeric plasmid at a copy number according to the measured LOD value in each reaction. PCR and real-time PCR assays were done and tested for stx1 and stx2 genes.

4. Results

4.1. Selection of Target Regions for Genes and Design of the Chimeric Sequence

Bioinformatic analysis showed the highest identity (100%) and coverage rates (100%) for the target sequences as compared with GenBank database. The chimeric sequence showed a 50% GC content. Analysis of secondary structure showed the least possibility for formation of secondary structures at intra-genic, inter-genic, and in the terminal sites (ΔG > -2). The desired fragment was inserted at HindIII site by GENEray Biotechnology Company. The chimeric plasmid presented the final length of 3881 bp.

4.2. Design and Construction of Primers for Gene Targets

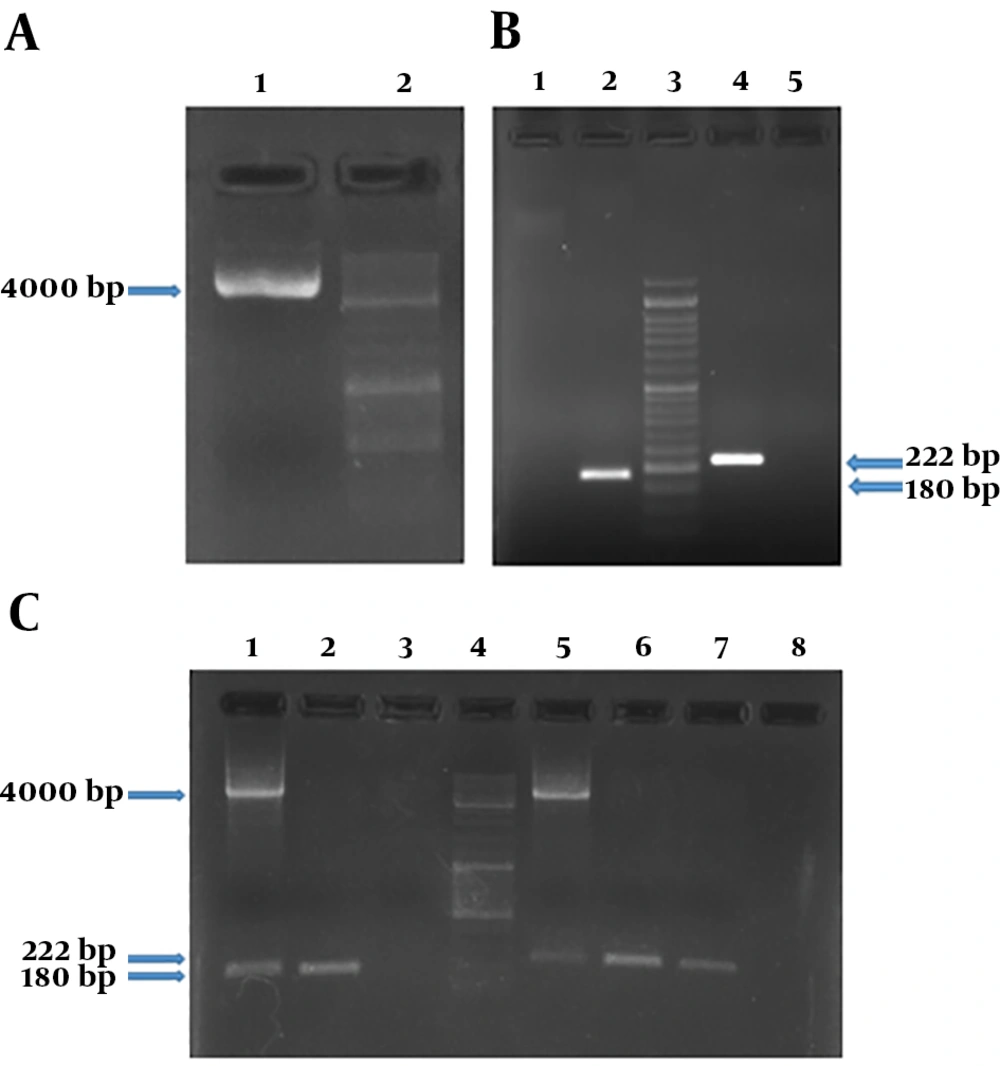

Based on the primer blast results, primers listed in Table 3 were approved based on characteristics, such as 3’ delta G, primer dimer, and Tm. Two sets of primers for Stx2 were used in a way to differentiate the chimeric variants from wild type ones in multiplex PCR reactions. PCR results confirmed the presence of chimeric plasmid and target genes in the plasmid extract of the transformants. PCR conditions are shown in supplementary file Appendix 1-6 in Supplementary File of the and results of amplification of the genes are shown in Figure 1.

| Name | Seq (5’ - 3’) | Tm | Product Size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| stx1F | ATAAATCGCCATTCGTTGACTAC | 57.08 | 180 |

| stx1R | AGAACGCCCACTGAGATCATC | 59.82 | |

| stx2F | GGCACTGTCTGAAACTGCTCC | 61.78 | 222 |

| stx2R | TCGCCAGTTATCTGACATTCTG | 58.39 | |

| eaeAF | GACCCGGCACAAGCATAAGC | 61.40 | 249 |

| eaeAR | CCACCTGCAGCAACAAGAGG | 61.40 | |

| hlyAF | GCATCATCAAGCGTACGTTCC | 59.82 | 278 |

| hlyAR | AATGAGCCAAGCTGGTTAAGCT | 58.39 |

The chimeric plasmid and related PCR products for stx1 and stx2 genes. A, The presence of purified plasmid was confirmed by bonding in 4 kb. Columns 1 and 2 show purified plasmid and the molecular weight marker DNA Ladder 100 bp, respectively; B, presence of stx1 (180 bp) and stx2 (222 bp) gene regions in the chimeric plasmid vector was confirmed. Columns 1 and 5 show negative controls (NTC) for stx1 and stx2, respectively; C, columns 1 to 8 show PCR products on positive control stx1 specimen (purified recombinant plasmid); PCR product on positive control stx1 specimen (chimeric plasmid); NTC of the stx1 gene region; the molecular weight marker DNA ladder 100 bp; PCR product on positive control stx2 specimen (purified recombinant plasmid); PCR product on positive control stx2 specimen (chimeric plasmid); PCR product on positive control stx2 specimen (chimeric plasmid); NTC of the stx2 gene region respectively.

4.3. Real-Time PCR Assay for Detection of Target Genes on the Vector

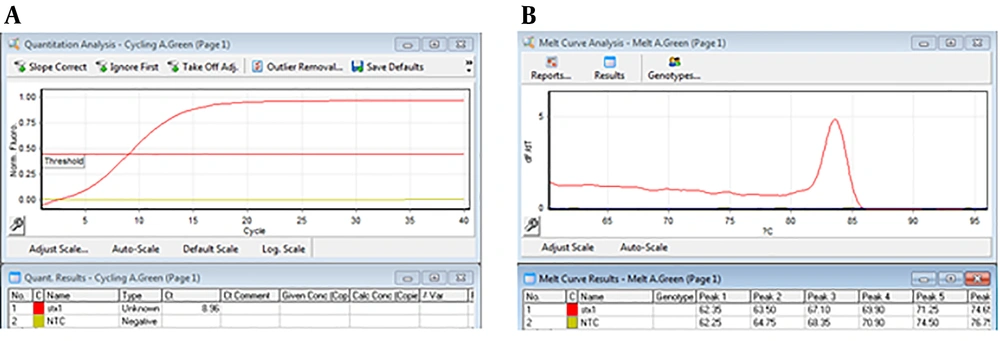

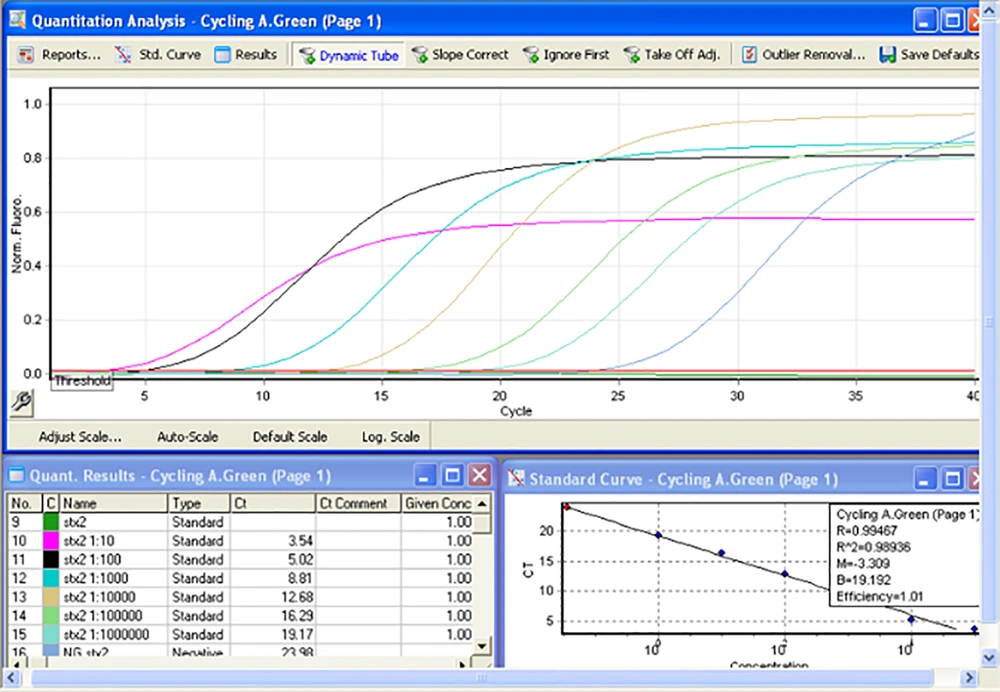

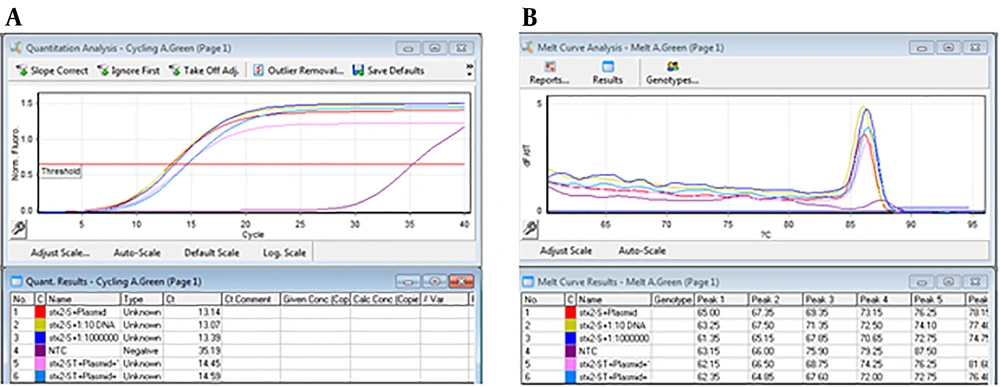

For performing real-time PCR assay, proper dilutions of the plasmid equivalent to defined copy number of target genes were prepared and analyzed using stx1 and stx2 specific primers. The optimal amplification conditions were achieved after comparing different temperatures and times, ramp of the machine, and melt curve analysis using Rotor-Gene Q software (Appendix 7-13 in Supplementary File). Amplification and melt curves of stx1 and stx2 genes are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

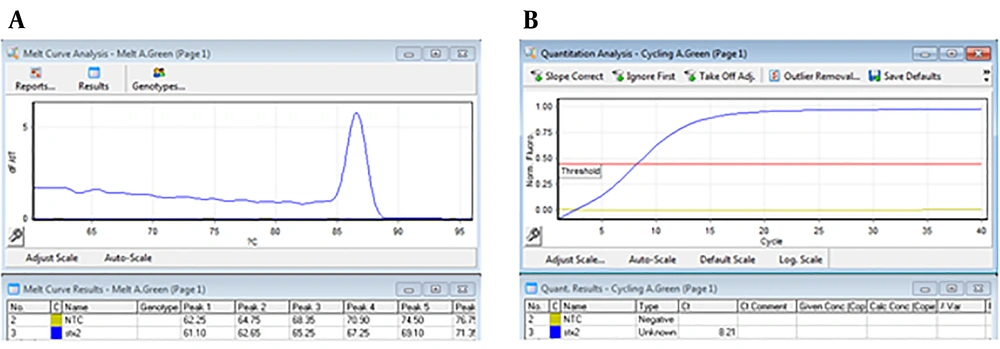

4.4. Evaluating the Primers’ Efficiencies and LOD

In order to determine the ability of target genes to be detected by primers using real-time PCR assay, concentration of the chimeric plasmid was determined by nanodrop machine, which its copy number per microliter was calculated as ~ 2.4 × 1010 copy/µL by the following formula:

That 10-6 to 10-1 dilutions of the plasmid (equivalent to 2.4 × 104 to 2.4 × 109 copies of plasmid) were used to evaluate the efficiency of primers and LOD. These dilutions were tested by stx1 and stx2 specific primers (Appendix 7-9 in Supplementary File). Desired results were obtained for tested primers (Slope -3 to -3.2, and efficiency of 100%) (Figures 4 and 5).

4.5. Measurement of LOD for Detection of STEC in the Spiked Human Stool

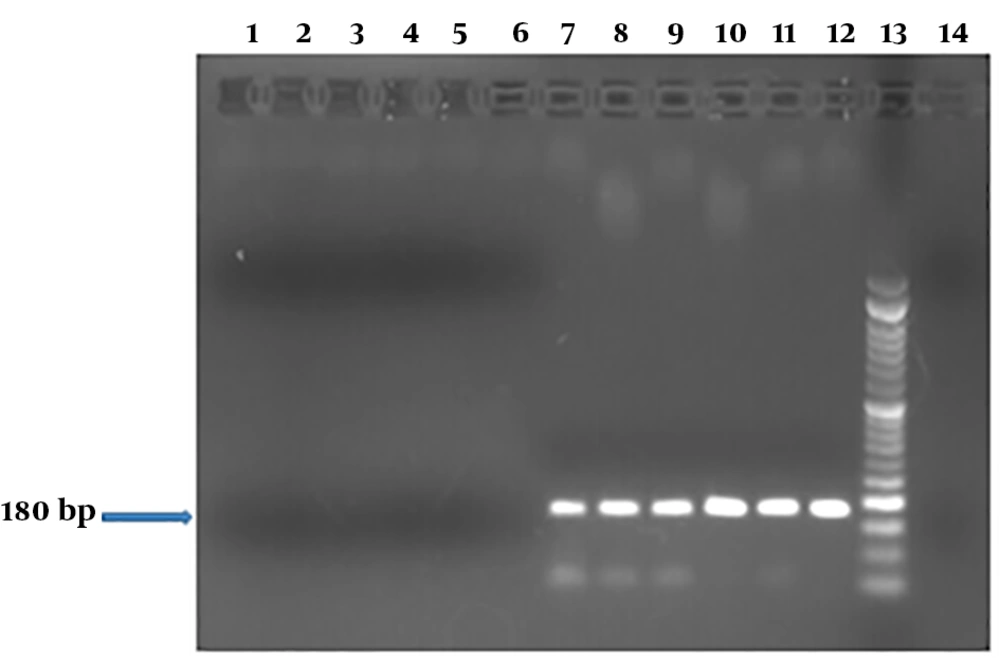

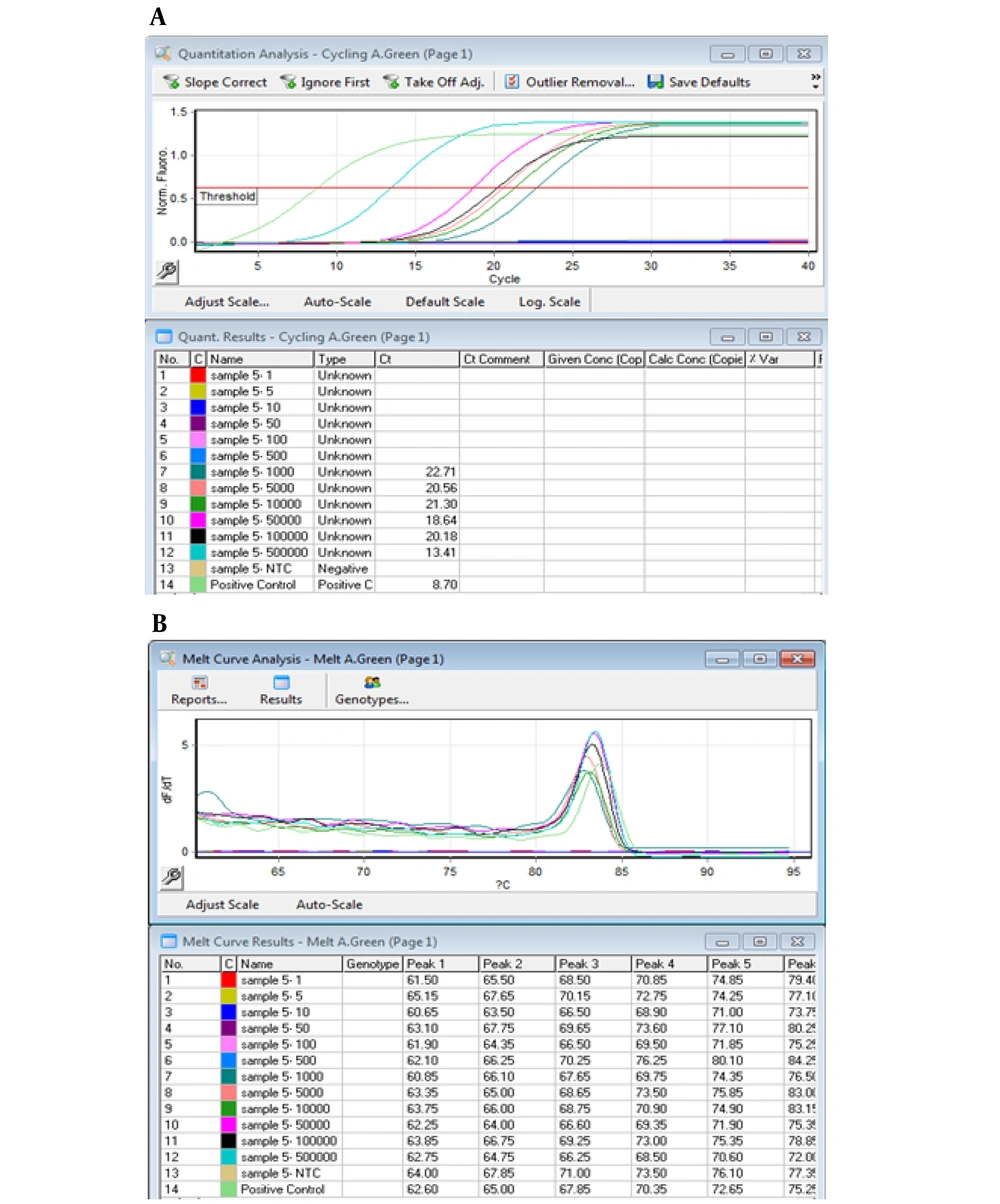

Analysis of the spiked stool samples with serial dilutions of recombinant E. coli DH5-α carrying the chimeric plasmid was showed performance of PCR method for detection of stx1 in the fecal specimens containing 5 × 105 CFU to 103 CFU bacteria; however, the method was unable to detect less than 103 CFU (LOD = 1000 CFU) (Figure 6). In real-time PCR, amplification of stx1 was shown for stool samples containing 5 × 105 CFU to 103 CFU of the inoculated bacterium (LOD = 103 CFU; Figure 7).

PCR products of stx1 in DNA extracts of the spiked stool specimens containing transformed E. coli DH5-α carrying chimeric plasmid at different cell numbers. Columns 1 to 14 show PCR products of the spiked stool samples with defined copy numbers of stx-encoding transformed E. coli strain (1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500, 103, 5 × 103, 104, 5 × 104, 105, and 5 × 105 CFU); lane 13, the molecular weight marker DNA Ladder 50 bp; lane 14, negative control. A LOD of 1000 was determined.

Amplification curve and melt curve analysis of products for stx1 gene in the spiked stool samples. Panel A shows amplification curve of stx1 gene in DNA extracts of the stool samples in the range of 5 × 105 to 103 CFU; panel B, melt curve analysis of the DNA extracts at defined concentrations.

4.6. Evaluation of the Repeatability and Sensitivity of the Assays

To calculate the repeatability of real-time PCR assay at 103 CFU to 5 × 105 CFU dilutions, the percentage of coefficient of variation was measured in a range of 3.3% to 16.1% (Table 4). TP, TN, FP, and FN values were determined after comparison of the results of PCR and real-time PCR assays (Tables 5 and 6). Similarly, to evaluate efficiency of the assay, the sensitivity, false negative, false positive, PPV, NPV, and total agreement of PCR assay were measured at different dilutions (Table 7). These results showed a 100% sensitivity for quantities of 5 × 105, 105, 5 × 104, 104, 5 × 103, 103, and 102 CFU per gram of stool, while this sensitivity decreased considerably in higher dilutions (1, 5, and 10 bacteria per gram of stool) (Table 7).

| CT1 | CT2 | STDEV. Pb | STDEV.P/Mean of Cq | CV, %c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 × 105 CFU | |||||

| 23.13 | 21.11 | 22.12 | 1.554852 | 0.074763303 | 7.4 |

| 18.96 | 20.99 | 19.975 | |||

| 26.59 | 19.7 | 23.145 | |||

| 20.94 | 17.38 | 19.16 | |||

| 20.34 | 18.83 | 19.585 | |||

| Mean of | 20.797 | ||||

| 105 CFU | |||||

| 25.11 | 26.9 | 26.005 | 4.413368 | 0.161721082 | 16.1 |

| 25 | 25.01 | 25.005 | |||

| 26.09 | 26.21 | 26.15 | |||

| 32.12 | 39.67 | 35.895 | |||

| 23.19 | 23.6 | 23.395 | |||

| Mean of | 27.29 | ||||

| 5 × 104 CFU | |||||

| 24.31 | 26.17 | 25.24 | 1.60557 | 0.068377398 | 6.8 |

| 22.94 | 23.25 | 23.095 | |||

| 22.84 | 22.71 | 22.775 | |||

| 21.94 | 20.13 | 21.035 | |||

| 25.17 | 25.35 | 25.26 | |||

| Mean of | 23.481 | ||||

| 104 CFU | |||||

| 26.64 | 28.28 | 27.46 | 1.956079 | 0.068583806 | 6.8 |

| 27.31 | 27.13 | 27.22 | |||

| 26.96 | 26.9 | 26.93 | |||

| 30.1 | 27.44 | 28.77 | |||

| 30.86 | 33.59 | 32.225 | |||

| Mean of | 28.521 | ||||

| 5 × 103 CFU | |||||

| 25.78 | 27.57 | 26.675 | 0.896976 | 0.032876738 | 3.3 |

| 27.94 | 29.61 | 28.775 | |||

| 26.59 | 26.54 | 26.565 | |||

| 27.07 | 25.99 | 26.53 | |||

| 27.78 | 27.96 | 27.87 | |||

| Mean of | 27.283 | ||||

| 103 CFU | |||||

| 30.31 | 33.72 | 32.015 | 2.117287 | 0.066621156 | 6.6 |

| 32.18 | 36.47 | 34.325 | |||

| 30.77 | 31.32 | 31.045 | |||

| 29.17 | 27.2 | 28.185 | |||

| 31.48 | 35.19 | 33.335 | |||

| Mean of | 31.781 | ||||

aThe Cq (Quantification cycle) mean value of the of the performed assays in five different specimens, each with two repetitions.

bThe standard deviation of the assay in different repetitions.

cCoefficient of variation: variation Percentage coefficient.

dMean

| E. coli DH5α-pGH-STEC CFU/g | PCR (+) | Real-Time PCR (+) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |

| 5 × 105 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 105 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 5 × 104 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 104 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 5 × 103 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 103 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 5 × 102 | -+ | -+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | -+ |

| 102 | -- | ++ | -- | ++ | -+ | -- | +- | ++ | -+ | -+ |

| 5 × 101 | -- | -- | -- | ++ | -- | -- | -- | ++ | -+ | -- |

| 101 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -+ | -- |

| 5 × 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -+ | -- |

| 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -+ | -- |

| E. coli DH5α-pGH-STEC, CFU/g | PCR (+) | TP | TN | FP | FN | Real-Time PCR (+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 × 105 | 10/10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10/10 |

| 105 | 10/10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10/10 |

| 5 × 104 | 10/10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10/10 |

| 104 | 10/10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10/10 |

| 5 × 103 | 10/10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10/10 |

| 103 | 10/10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10/10 |

| 5 × 102 | 8/10 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9/10 |

| 102 | 5/10 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5/10 |

| 5 × 101 | 2/10 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 3/10 |

| 101 | 0/10 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 1/10 |

| 5 × 100 | 0/10 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 1/10 |

| 100 | 0/10 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 1/10 |

Abbreviations: FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

| Different Dilution | |

|---|---|

| 5 × 105 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 0/10 + 0 = 0 |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 10 + 0/10 + 0 + 0 + 0 = 100% |

| 105 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 0/10 + 0 = 0 |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 10 + 0/10 + 0 + 0 + 0 = 100% |

| 5 × 104 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 0/10 + 0 = 0 |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 10 + 0/10 + 0 + 0 + 0 = 100% |

| 104 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 0/10 + 0 = 0 |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 10 + 0/10 + 0 + 0 + 0 = 100% |

| 5 × 103 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 0/10 + 0 = 0 |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 10 + 0/10 + 0 + 0 + 0 = 100% |

| 103 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 0/10 + 0 = 0 |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 10/10 + 0 = 100% |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 10 + 0/10 + 0 + 0 + 0 = 100% |

| 5 × 102 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 8/8 + 1 = 88% |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 1/8 + 1 = 11% |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 1 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 8/8 + 0 = 100% |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 1/1 + 1 = 50% |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d | 8 + 1/8 + 0 + 1 + 1 = 90% |

| 102 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 5/5 + 0 = 100% |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 0/5 + 0 = 0 |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 5 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 5/5 + 0 = 100% |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 5/0 + 5 = 100% |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 5 + 5/5 + 0 + 0 + 5 = 100% |

| 5 × 101 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 2/2 + 1 = 66% |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 1/2 + 1 = 33% |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 7 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 2/2 + 0 = 100% |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 7/1 + 7 = 87.5% |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 2 + 7/2 + 0 + 1 + 7 = 90% |

| 101 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 0/0 + 1 = 0 |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 1/0 + 1 = 100% |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 9 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 9/1 + 9 = 90% |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 0 + 9/0 + 0 + 1 + 9 = 90% |

| 5 × 100 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 0/0 + 1 = 0 |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 1/0 + 1 = 100% |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 9 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 9/1 + 9 = 90% |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 0 + 9/0 + 0 + 1 + 9 = 90% |

| 100 CFU | |

| Sensitivity: a/(a + c) | 0/0 + 1 = 0 |

| False negative %: c/(a + c) | 1/0 + 1 = 100% |

| False positive %: b/(b + d) | 0/0 + 9 = 0 |

| Positive predictive value: a/(a + b) | 0/0 + 0 = 0 |

| Negative predictive value: d/(c + d) | 9/1 + 9 = 90% |

| Total agreement: a + d/(a + b + c + d) | 0 + 9/0 + 0 + 1 + 9 = 90% |

4.7. Evaluation of Chimeric Plasmid Vector as an Internal and External Control for Shiga-Toxigenic Escherichia coli Detection by PCR Method

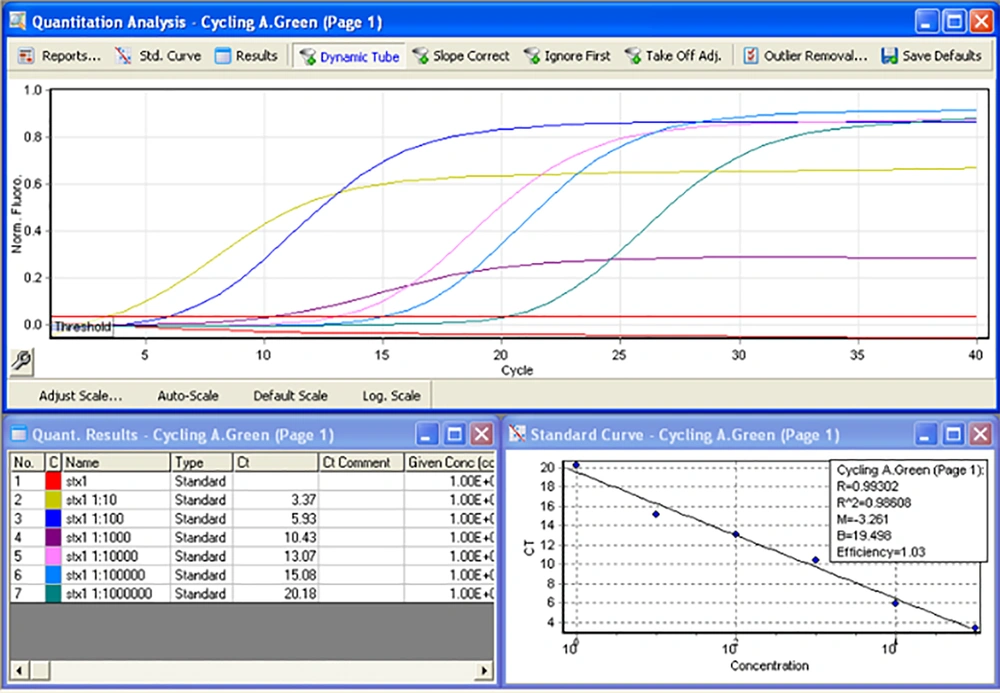

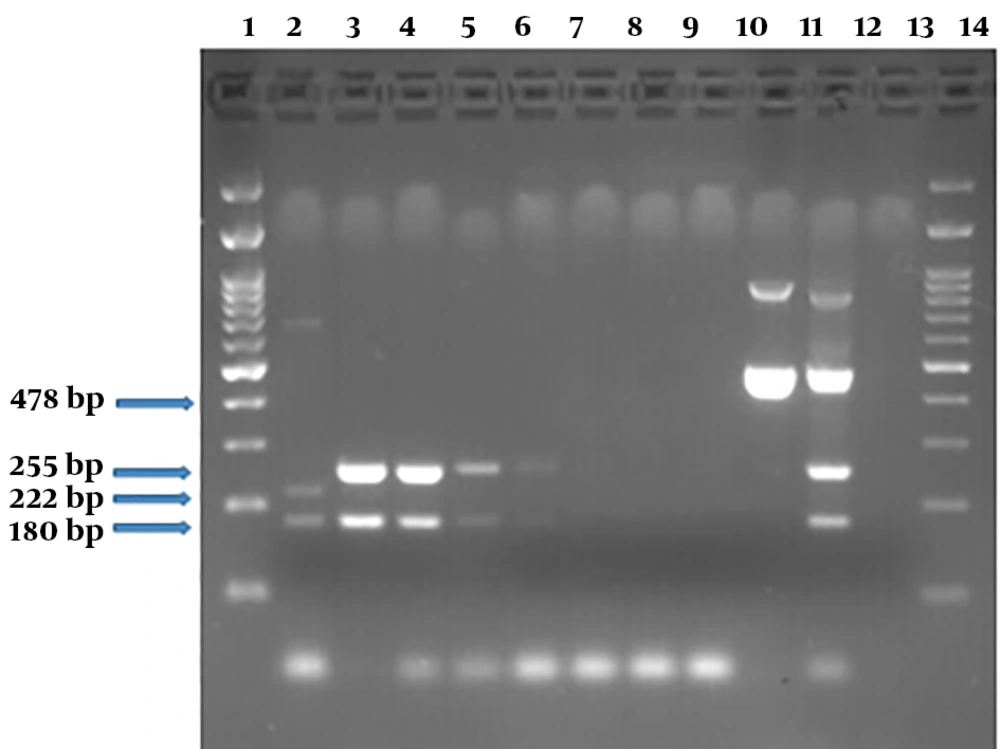

In order to analyze the capability of the chimeric vector for application as internal control, a pair of secondary primers were used in the multiplex reaction (Tables 8 and 9). Accordingly, PCR assay was performed for stx1 and stx2 on serial dilutions of DNA extract of E. coli O157:H7, (equivalent to 2 × 103 to 2 × 109 copies of DNA), in the presence of chimeric plasmid vector (103 copies of the plasmid). The results indicated the ability of the primers to detect stx1 and stx2 genes in both the synthetic vector and the target DNA, when they were analyzed separately (Figure 8). This result confirmed the application of the vector as an external control for PCR; however, the multiplex reaction did not confirm its application as an internal control, due to interference with targeted sequences on the chromosomal DNA. Similarly, in real-time PCR, the results showed that different primers cannot create distinct melt curve peaks in single reaction to dissociate products of vector from the bacterial target DNA. However, usage of the vector as an external control was confirmed in real-time PCR method.

| Components | Initial Concentration | Used Volume |

|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA polymerase (2× master mix) | 2 × | 10 µL |

| PF stx1 | 10 µM | 0.5 µL |

| PR stx1 | 10 µM | 0.5 µL |

| PF stx2 | 10 µM | 0.5 µL |

| PR stx2 | 10 µM | 0.5 µL |

| Plasmid DNA | 100 ng/µL | 1 µL |

| Chromosal DNA | 3280 ng/µL | 3 µL |

| Injection D.W. | - | 9 µL |

| Total | - | 25 µL |

Serial dilutions electrophoresis of E. coli O157 DNA containing internal and external control (PCR products) on 2% agarose gel. Here, 180 bp and 222 bp regions are related to stx1 and stx2 on chimeric plasmid, respectively. DNA lane 1, molecular weight marker DNA ladder 100 bp; lane 2, PCR products of a specimen containing chimeric plasmid; lanes 3 - 9, the presence of stx1 and stx2 PCR products associated with chromosomal DNA at 2 × 109 to 2 × 103 Copies in the stool samples; lane 10, stx1 PCR product (478 bp) by new primer sets at a concentration equal to 2 × 108 copies of E. coli O157; lane 10, lane 11, PCR products of a sample containing chimeric plasmid plus E. coli O157 using two pairs of distinct primer sets; lane 12, negative control; lane 13, the molecular weight marker DNA ladder 100 bp.

4.8. Evaluation of Chimeric Plasmid Vector as an Internal and External Control for Shiga-Toxigenic Escherichia coli Detection by Real-Time PCR

In order to evaluate the chimeric plasmid vector as an internal and external control for detection of Shiga-toxigenic E. coli, real-time PCR assay was performed on two dilutions of standard E. coli O157 DNA (10-1 and 10-6 dilutions equivalent to 2 × 103 and 2 × 108 copies of DNA), in the presence of the chimeric plasmid and its specific primers as described in Table 10 and Appendix 9 in Supplementary File. The results, as was shown in Figure 9, showed interference of the plasmid with template wild type DNA for amplification of the targeted gene when they present in the same reaction, concurrently.

| Components | Initial Concentration | Used Volume |

|---|---|---|

| RealQ plus 2× master mix | 2 × | 10 µL |

| PF | 10 µM | 0.2 µL |

| PR | 10 µM | 0.2 µL |

| Plasmid DNA | 100 ng/µL | 1 µL |

| Chromosal DNA | 3280 ng/µL | 3 µL |

| Injection D.W. | - | 5.6 µL |

| Total | - | 20 µL |

Amplification curve and melt curve for detection of stx2 in the spiked stool samples using real-time PCR. Panel A, shows amplification of stx2 gene in three states: (1) 10-1 and 10-6 dilutions of chromosomal DNA (equivalent to 2 × 108 CFU/ml and 2 × 103 copies of DNA) and the specific primers of the chimeric plasmid, (2) 10-1 and 10-6 dilutions of chromosomal DNA (equivalent to 2 × 108 CFU/mL and 2 × 103 copies of DNA) and its specific primers in the presence of the plasmid DNA and its specific primers, and (3) DNA of chimeric plasmid and its specific primers; panel B. The melt curves did not show differences based on the targeted gene regions and the length of related PCR products.

5. Discussion

Infection with STEC is a worldwide public health concern. This bacterium accounts for 7% - 47.7% of diarrhea cases among patients at different age groups in Iran (18, 19). Rapid detection of STEC infection is a laboratory priority, which requires design and validation of novel methods. An ideal detection method needs to satisfy five premier requirements, including high specificity (detecting only the bacterium of interest), high sensitivity (capable of detecting as low as a single live bacterial cell), short time-to-results (minutes to hours), great operational simplicity (no need for lengthy sampling procedures and use of specialized equipment) and cost-effectiveness. Culture as a standard method takes long time to give the final result and cannot reveal the presence of these toxigenic bacteria alone. On the other hand, PCR, antibody-based techniques, and biosensors offer shorter turnaround time, but they require the use of expensive reagents and sophisticated equipment, which make the method expensive (20).

Real-time PCR as a fairly fast-diagnostic method allows identification of positive samples during the amplification cycles of target gene fragments before the run ends. Nowadays, real-time PCR based commercial kits are available for diagnosis of prokaryotic and eukaryotic gene targets that can be automated. Therefore, real-time PCR is very useful for laboratories, because it needs less training of user, infrastructures and facilities, the reaction compounds containing all PCR reagents are commercially available and these tests provide quick results (21). Real-time PCR provides the ability to measure the amount of a particular microorganism in the sample theoretically, and no need for post-amplification treatment of the samples, such as gel electrophoresis, which reduces turnaround time (22, 23).

There are many questions about using this technique to detect STECs in stool and food samples. Several factors, such as the initial number of target bacterium in a sample, type and volume of samples, presence of non-target microbiota, PCR inhibitors, and protocols used to prepare template DNA can have a significant effect on the sensitivity of real-time PCR assays that are used for detection of these bacteria (4). Inhibition of PCR is a common problem when DNA extracts from food, the environment, and clinical specimens use as a template. This interference is because of the presence of substances such as heme in blood and meat specimens, heavy metals, humic acids and fulvic substances in the stool and soil, and polyphenolic compounds in acidic foods (24, 25). The inhibitors can also suppress the fluorescence signal from fluorophores used in these assays. The problems of PCR inhibitors can be partially solved by further purification of DNA and spiking of test samples with PCR amplification internal control (IC), or other sequences that are not present in target bacterium (4).

Internal control can be a natural gene sequence in the cell, which is expected to be present in all specimens. This type of IC will be suitable in samples where the integrity of the target nucleic acid is maintained, but in samples that are improperly collected, stored, or processed, there is no proper internal target and so IC fails to produce a positive result. Another disadvantage of this type of PCR control is that the selected internal sequences may not reflect the amplification of the original target due to differences in the primer sequences, amplified product’s size and the relative amounts of two targets. However, incorporation of IC within PCR-based assays in samples that prepared properly increases the sensitivity of the assay by enabling the user to identify and retest samples containing PCR inhibitors. In addition, a positive result for IC indicates that amplification has occurred and thus ensures that the result of the negative test is really negative. For routine clinical applications, the laboratory can maximize the sensitivity of the test by using IC for monitoring of effective amplification of the target gene in each sample. Using external control is recommended in cases where the use of the internal control affects the reaction. Accordingly, the IC may optionally be used to increase the efficiency of PCR and real-time PCR methods when it has not compromised the reaction performance (26).

A number of STEC genes, such as stx1, stx2, and eae, are considered suitable candidates for use as control for the amplification assays, but none of them can guarantee proper recognition of STEC strains if used alone. In the present study, we tried to construct a chimeric vector containing stx1, stx2, eae and ehxA genes to evaluate its efficiency as internal or external controls in PCR and real-time PCR reactions. Extracted DNA samples from stool of patients with gastroenteritis were spiked with 10 fold dilutions of wild type STEC, chimeric plasmid, and STEC + chimeric plasmid, in different assays. No major reduction in the sensitivity of PCR reactions was detected after addition of STEC in different numbers. Results of the assays showed that feces inhibitors did not affect the reaction, when 5 × 105 CFU to 103 CFU of STEC were existed in each sample. While the use of chimeric vector as external control was confirmed in the PCR assay, our results showed that the built-in chimeric vector lack of proper function for use as an IC for the PCR reaction. This issue was mainly due to the formation of non-specific and primer dimer bands in the samples that were spiked with a mixture of STEC + chimeric plasmid.

The application of designed chimeric plasmid was examined in this study for usage in real-time PCR, to show the IC and STEC associated genes in a single reaction. The results did not confirm the application of IC for use in real-time PCR, since it was not able to differentiate wild type from a chimeric variant of stx1 during the amplification process. Comparison of the sensitivity of PCR and real-time PCR reactions for identifying the coding genes on the chimeric vector and these genes in DNA of the bacterial inoculum in the stool samples showed an acceptable sensitivity and appropriate LOD (103 copies of DNA), which was comparable to the results of other researchers. Gerritzen et al. (27) compared real-time PCR with culture, ELISA and cell culture methods for detection of STEC and calculated the LOD rate as 103 CFU/mL (equivalent to 10 CFU/PCR per reaction). They put cultivation as a golden standard method (27). Li et al. (28) compared Taqman multiplex real-time PCR method with PCR, and obtained LOD rate as 40 CFU/reaction for detection of STEC (28). Belanger et al. (29) calculated the LOD rate as 105 CFU/g. In a similar study, Piskernik et al. (30) calculated the LOD rate as 1.1 × 102 CFU/mL for E. coli O157:H7. The method of Belanger et al. (29) was able to detect 105 CFU/g stool and the method of Salinas-Ibanez et al. (31) was able to detect 3.15 × 104 DNA copy.

Concerning the sensitivity of the STEC detection response, our results indicated that the sensitivity of the PCR assay depends on the concentration of target DNA in the samples, as the sensitivity rate decreased considerably by decreasing the concentration of target DNA to ≤ 102 copies. Application of the chimeric vector as an external control for assessment of infection with STEC in stool samples was confirmed in our experiment. Lack of a difference in the melting temperatures of stx1 gene variants of the vector and the wild type strain in real-time PCR reaction rejected the use of this vector as an internal control in real-time PCR reaction. These results also showed that although the real-time PCR assay conditions had proper repeatability for detection of STEC, changes in the Ct values of the products in independent assays confirm the need for more optimization and standardization of reactions.

In this study, Ct values showed less than one cycle variation (0.9 - 4.4 cycles) in the control plasmid among various experiments. This analysis showed an acceptable CV% with a study by Baker et al. (32). The CV% obtained by Yang et al. (33) in the SYBR green method was less than 2%, while Tawe (13) reported a CV% of 0.2 to 2.8. The amount of CV% obtained by Baker et al. (32) was similar to the present study and was in the range of 3.16 to 16.82. In the present study, the results of using wild type strains and spiked samples for PCR and real-time PCR validation reflected the ideal state for stx1 gene detection. These results showed a relatively low LOD for correct identification of stx genes from all spiked stools with a concentration equivalent to 103 CFU of STEC.

5.1. Conclusions

The results of this study confirmed the efficiency of synthetic plasmid vector for detection of stx1, stx2, eae, ehxA genes as an external control in PCR and real-time PCR assays. Evaluation of the primers used in this study showed that they can act similarly in various stool specimen, where the microbiota in these matrices do not interfere with the detection of the intended STEC targets. Although PCR and real-time PCR assays showed relatively acceptable results for detection of STEC, the usage of designed chimeric vector was not approved as an internal control, in spite of its proper application as an external control. Our results showed LOD of 103 CFU/g, sensitivity of 66% to 100%, percent coefficient of variation of 3.3% to 16.1%, and primers’ efficiencies of 100%. Comparison of the results showed real-time PCR assay as a more sensitive assay than conventional PCR for detection of STEC. Rapid diagnosis of microbial agents in clinical samples could help clinicians to prescribe appropriate medication for better management of diseases. Moreover, the results of this study confirmed application of PCR and real-time PCR methods for detection of STEC in stool samples of patients with diarrhea. These methods could reduce turnaround time for laboratory reports to 1 day, which is three-times faster than those attained by conventional methods.