1. Background

Today's world is grappling with drug abuse and dependence as one of its most pressing and costly health problems (1). Drug abuse and addiction have debilitative effects on individuals, the community, and culture. Therefore, these factors motivate patients and medical professionals to prevent, stop, and avoid relapse. One of the emerging areas in this field is mindfulness, which is known to play a key role in most psychiatric disorders (2).

Regarding substance abuse and mindfulness, it has been theorized that individuals with high levels of mindfulness are better able to perceive treatment experiences as transient and are less likely to engage in addictive behaviors (3). However, a negative correlation has been denoted between mindfulness and substance use behaviors. Acting with awareness, non-judgment, and non-reactivity has a negative and significant association with substance use behaviors. Mindfulness could be considered a significant ability to understand, evaluate, and accept the emotions that may be involved in therapeutic behaviors in addiction (4).

Previous findings have shown significant associations between mindfulness practices and various psychological outcomes, such as lower impulsivity and addiction symptoms (5). Addictive behaviors are also associated with low levels of mindfulness. The rapid growth of substance abuse requires various tools to measure the mindfulness level of addicts consistent with ethnocultural and structural factors.

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) is the most widely used questionnaire in this regard, which was also used in the present study to measure mindfulness in terms of attention (6). Another important tool is the five facet mindfulness questionnaire (7), which measures five factors associated with the construct of mindfulness. In addition, the Freiburg mindfulness inventory (8) has been designed to measure the state of mindfulness after a meditation retreat. Finally, the Toronto Mindfulness Scale (9) measures the state of the mindful self-regulation of attention and approach to experience.

Out of several psychometric tests that have been developed to measure mindfulness, the MAAS is probably the most widely researched and used approach, which assesses individual differences in the frequency of mindful states over time (6). The MAAS is a 15-item self-report measure (6) developed to evaluate mindfulness. It has been validated and translated to several languages, including Swedish (10), French (11), and Spanish (12). Nevertheless, the scale has not been used explicitly for a population of substance abusers.

It is essential to guarantee culturally relevant questionnaire items for the Iranian population to address external validity and avoid misinterpretations regarding the meaning of specific items. As such, it is critical to adapt and validate the MAAS to sample Iranian substance abusers and further the advancement of mindfulness research in a culturally appropriate manner and investigate different aspects of mindfulness in samples of Iranian substance abusers.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to validate the Persian version of the MAAS in a sample of Iranian substance abusers.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This descriptive-analytical, cross-sectional study was conducted on all the male substance abusers receiving treatment in Tehran, Iran. The samples had been referred to public or private medical centers during April 2017-December 2018.

The sample population included 753 men with substance abuse disorders who were studied in five groups, including methadone-treated, buprenorphine-treated, opium tincture-treated (tenturapium), out-of-treatment, and patients who were members of the narcotics anonymous (N.A.). The subjects were selected via convenience sampling from among the patients referred to addiction treatment clinics, compulsory treatment camps, and N.A. in Tehran.

3.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria of the study were as follows: (1) age of 18 - 71 years; (2) basic literacy; (3) no history of specific psychiatric disorders and (4) willingness to participate. In case of difficulty in reading/understanding the questionnaires, the items would be read out and explained by calling. Absence of psychiatric disorders was considered based on participants' self-report and not on psychiatric interviews.

3.2. Measures

A demographic checklist was used to collect data on age, marital status, education level, history of substance use in the family, and onset of substance abuse.

3.2.1. Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) has been developed by (6) to assess awareness and attention to current events and experiences in daily life. It is a 15-item scale based on a six-point Likert Scale (almost always = 1, almost never = 6). The total score of mindfulness in the MAAS is within the range of 15 - 90, with the higher scores indicating high levels of mindfulness. In Iran, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient has been estimated at 0.90 for the general population (13).

3.2.2. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21

In 1995, Lovibond and Lovibond developed a 21-item scale to assess stress, anxiety, and depression, known as the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21). The validity of the scale is estimated at 0.77 by (14). In Iran, the internal consistency of the DASS-21 has been confirmed at the Cronbach's alpha of 0.82 (15).

3.2.3. General Self-efficacy Scale

The General Self-efficacy (GSE) scale was developed by Schwarzer and Jerusalem in 1979 and revised in 1981 into 10 items, which measure general self-efficacy. The items are scored based on a four-point Likert scale within the range of 1 - 4. In Iran, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale has been estimated at 0.81, and its reliability was also confirmed for substance abusers using the test-retest method (16).

3.2.4. The Aggression Scale

The aggression scale measures 11 indicators of aggressive behaviors/responses, which range from zero times to six or more times. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, as a measure of internal consistency, has been estimated at 0.78 (17). The Persian version of the aggression scale has been validated in Iran, and the reliability of the scale has also been confirmed at the Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 (18).

3.2.5. Quality of Mindfulness Scale

The Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R) (19) is a 12-item scale to measure everyday mindfulness. The items are scored based on a four-point Likert Scale (not at all = 1, almost always = 4) (20). In Iran, the Cronbach's alpha of the scale has been reported to be 0.80, and the test-retest reliability has also been confirmed.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

All the procedures and objectives of the current research regarding human research complied with the ethical standards of the National Research Committee, the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), subsequent revisions, and equivalent ethical norms. The participants provided implied consent, and written informed consent elements were incorporated into the internet invitation.

3.4. Procedure

The study was conducted in two stages; the first stage involved the translation and cultural adaptation of the instrument, and the second stage involved the analysis of its psychometric properties and evaluating validity and reliability. The MAAS was translated into Persian in the first stage via back-translation. The technique was implemented by a translation team who translated the scale into the target language, and a second team back-translated the scale to the original language. Moreover, three translators were asked to assist this process. The translators served independently so that there would be no significant differences in the interpretation and presentation of the applied methods. Finally, a professor of English studies modified some of the items so that they could be comprehensible to the general population. Measures were also taken to ensure that the length of the items was similar to the original scale.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The research was divided into two stages, and the cross-validation technique was used to assess validity. Exploratory factor analysis EFA was performed on half of the samples in the first stage using principal component analysis (PCA) and the VARIMAX rotation method. Since the obtained results in the Iranian population were similar to the original samples, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on the other half of the subjects to confirm the factor structure of the questionnaire. Demographic characteristics and Pearson’s correlation-coefficient between the Persian version of MAAS, DASS-21, the aggression scale, the GSE scale, and the quality of mindfulness scale were analyzed in SPSS version 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Inc., Armonk, USA). In addition, a single-factor structure was used to analyze the internal structure of the MAAS in LISREL version 8.8.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

In total, 753 Iranian substance abusers completed the survey. The mean score of the Persian version of the MAAS for the Iranian substance abusers was within the range of 3.04 ± 1.48 - 4.61 ± 1.53 (Table 1). As mentioned earlier, the present study was conducted in two stages of EFA and CFA.

| No. (%) | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 255 (66.13) | 56.24 ± 14.45 |

| Single/widow, divorce | 498 (33.86) | 51.67 ± 14.01 |

| Education level | ||

| Elementary | 169 (22.24) | 51.02 ± 9.02 |

| Cycle/middle certificate | 268 (35.59) | 51.53 ± 10.21 |

| Diploma | 219 (29.08) | 54.92 ± 11.56 |

| Associate degree | 14 (1.85) | 55.74 ± 80.36 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 62 (8.23) | 57.62 ± 9.42 |

| Master’s degree (or higher) | 21 (2.78) | 60.07 ± 7.91 |

| Substance abuse (illegal drugs) in family | ||

| Yes | 324 (40.02) | 52.42 ± 14.47 |

| No | 429 (56.98) | 53.82 ± 13.27 |

| Onset of substance use (y) | ||

| ≥ 18 | 278 (36.91) | 51.97 ± 10.23 |

| < 18 | 475 (63.08) | 53.95 ± 14.73 |

Table 2 shows the calculated inter-item and item-total correlation matrix.

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| m2 | 0.352** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| m3 | 0.374** | 0.442** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| m4 | 0.249** | 0.327** | 0.337** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| m5 | 0.365** | 0.379** | 0.318** | 0.443** | 1 | |||||||||||

| m6 | 0.274** | 0.386** | 0.277** | 0.342** | 0.372** | 1 | ||||||||||

| m7 | 0.372** | 0.437** | 0.386** | 0.452** | 0.450** | 0.419** | 1 | |||||||||

| m8 | 0.277** | 0.415** | 0.402** | 0.414** | 0.365** | 0.397** | 0.558** | 1 | ||||||||

| m9 | 0.273** | 0.347** | 0.374** | 0.419** | 0.449** | 0.289** | 0.431** | 0.476** | 1 | |||||||

| m10 | 0.290** | 0.358** | 0.354** | 0.388** | 0.449** | 0.304** | 0.586** | 0.567** | 0.547** | 1 | . | |||||

| m11 | 0.152** | 0.169** | 0.053 | 0.133** | 0.129** | 0.060 | 0.216** | 0.222** | 0.141** | 0.247** | 1 | |||||

| m12 | 0.304** | 0.404** | 0.323** | 0.360** | 0.304** | 0.427** | 0.356** | 0.456** | 0.333** | 0.353** | 0.118** | 1 | ||||

| m13 | 0.244** | 0.289** | 0.284** | 0.224** | 0.175** | 0.224** | 0.348** | 0.351** | 0.262** | 0.257** | 0.326** | 0.311** | 1 | |||

| m14 | 0.267** | 0.472** | 0.439** | 0.426** | 0.394** | 0.351** | 0.512** | 0.670** | 0.517** | 0.508** | 0.206** | 0.521** | 0.403** | 1 | ||

| m15 | 0.283** | 0.332** | 0.305** | 0.325** | 0.404** | 0.301** | 0.369** | 0.399** | 0.379** | 0.441** | 0.134** | 0.376** | 0.129** | 0.475** | 1 | . |

| Total | 0.534** | 0.651** | 0.604** | 0.628** | 0.646** | 0.583** | 0.736** | 0.744** | 0.669** | 0.711** | 0.348** | 0.634** | 0.511** | 0.765** | 0.604** | 1 |

a**Correlation significant at 0.01 (2-tailed)

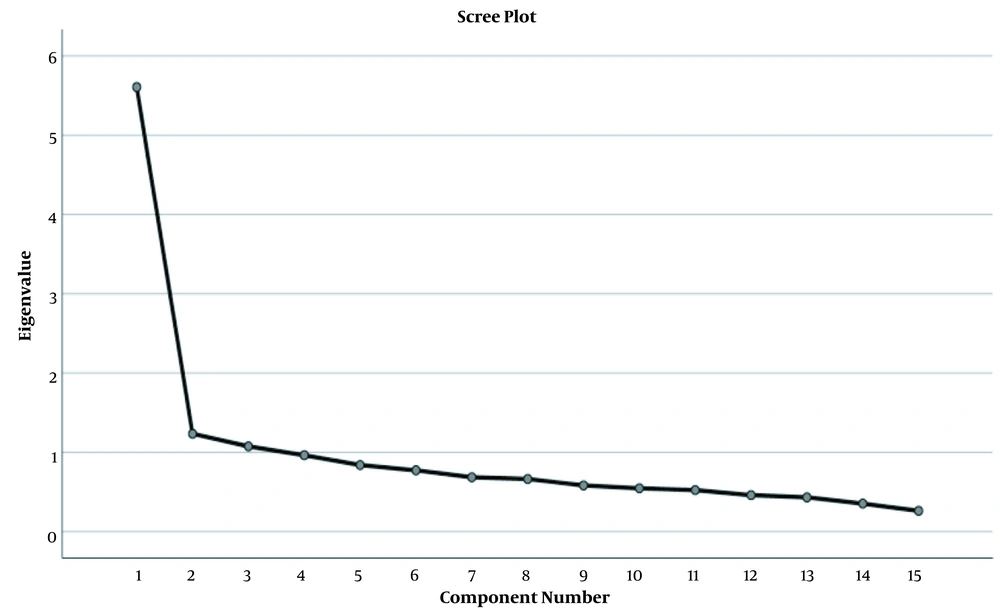

The internal structure of the Persian MAAS in the Iranian substance users was calculated to be -15 by the EFA using the PCA and VARIMAX rotation. In addition, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index was estimated at 0.89, exceeding the recommended value (0.6). Bartlett's test of sphericity also reached statistical significance (x2 = 1512.74; P < 0.001), indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. On the other hand, the results of the initial analysis revealed three factors with an Eigenvalue of > 1, explaining 52.77% of the variance. The PCA also indicated that the total factor loading on a single factor exceeded 0.40, except for item 11 (Table 3 and Figure 1)

| Factor Loading | Cronbach's Alpha (If Item Deleted) | Corrected Item-total Correlation | Eigenvalue | Total Alpha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Variance (%) | Cumulative (%) | |||||

| Item 1 | 0.491 | 0.870 | 0.428 | 5.606 | 37.376 | 37.37 | 0.874 |

| Item 2 | 0.614 | 0.865 | 0.539 | 1.234 | 8.227 | 45.60 | |

| Item 3 | 0.567 | 0.868 | 0.483 | 1.075 | 7.169 | 52.77 | |

| Item 4 | 0.620 | 0.865 | 0.540 | 0.963 | 6.423 | 59.19 | |

| Item 5 | 0.612 | 0.865 | 0.532 | 0.839 | 5.596 | 64.79 | |

| Item 6 | 0.526 | 0.869 | 0.444 | 0.773 | 5.154 | 69.94 | |

| Item 7 | 0.746 | 0.858 | 0.676 | 0.685 | 4.569 | 74.51 | |

| Item 8 | 0.736 | 0.859 | 0.657 | 0.663 | 4.423 | 78.93 | |

| Item 9 | 0.653 | 0.864 | 0.567 | 0.583 | 3.885 | 82.82 | |

| Item 10 | 0.709 | 0.861 | 0.630 | 0.546 | 3.643 | 86.46 | |

| Item 11 | 0.257 | 0.880 | 0.212 | 0.524 | 3.492 | 89.95 | |

| Item 12 | 0.613 | 0.865 | 0.535 | 0.460 | 3.064 | 93.02 | |

| Item 13 | 0.464 | 0.871 | 0.404 | 0.432 | 2.880 | 95.90 | |

| Item 14 | 0.787 | 0.856 | 0.717 | 0.353 | 2.354 | 98.25 | |

| Item 15 | 0.573 | 0.867 | 0.487 | 0.262 | 1.746 | 100.00 | |

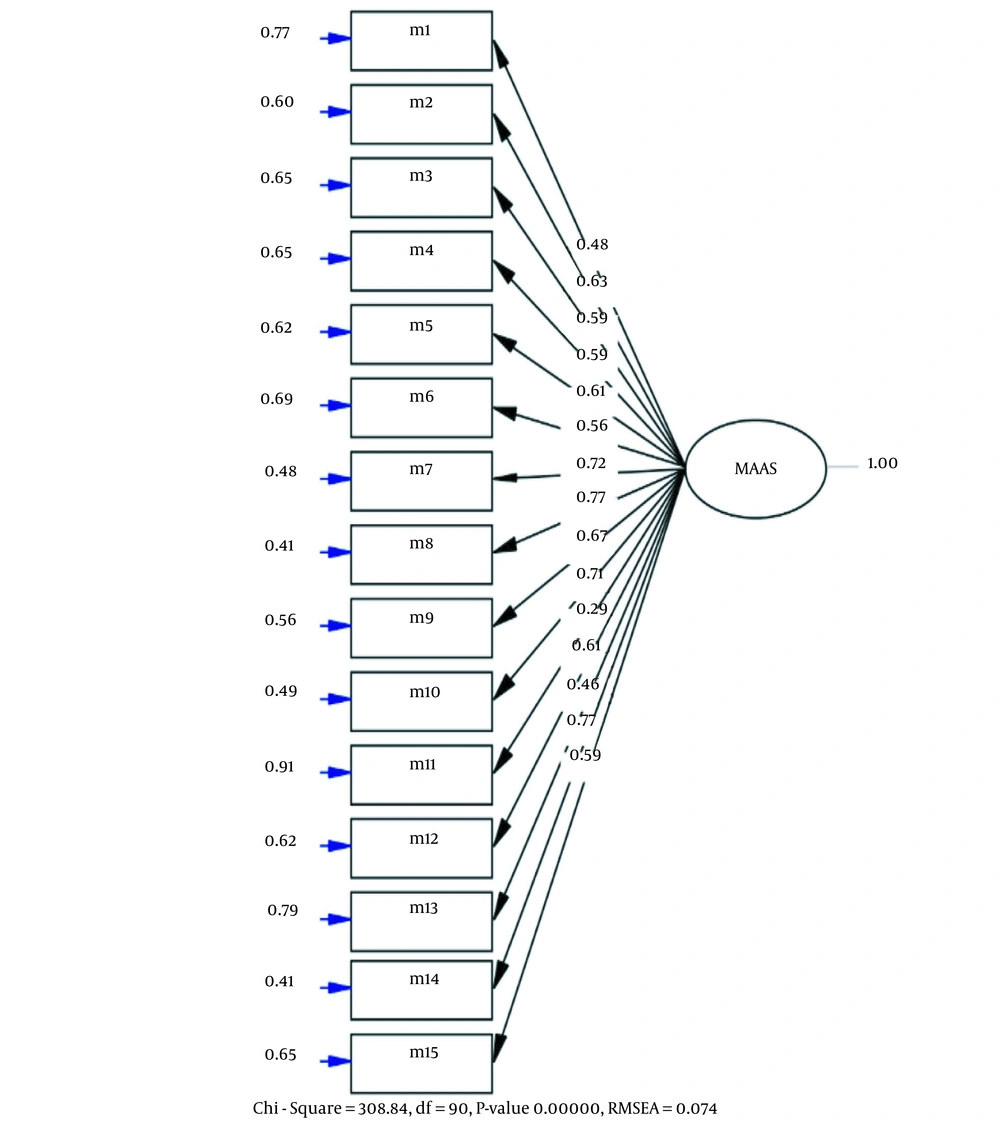

According to the CFA, 446 drug abusers with the mean age of 35.9 ± 7.11 years were studied. As for marital status, 281 subjects (63%) were single, and 165 (36.9%) were married. In terms of employment status, the participants were divided into different categories; 216 cases (48.4%) were unemployed, 123 (27.5%) were part-time workers, and 107 subjects (23.9%) were employed. (Figure 2 and Table 4)

| Items | Factor Loading | Eigenvalue | Total Alpha | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Variance (%) | Cumulative (%) | |||

| Item 1 | 0.48 | 6.279 | 41.859 | 41.859 | 0.897 |

| Item 2 | 0.63 | 0.989 | 7.437 | 49.296 | |

| Item 3 | 0.59 | 0.952 | 6.347 | 55.642 | |

| Item 4 | 0.59 | 0.856 | 5.709 | 61.351 | |

| Item 5 | 0.61 | 0.788 | 5.254 | 66.605 | |

| Item 6 | 0.56 | 0.737 | 4.916 | 71.521 | |

| Item 7 | 0.72 | 0.631 | 4.204 | 75.725 | |

| Item 8 | 0.77 | 0.596 | 3.970 | 79.696 | |

| Item 9 | 0.67 | 0.542 | 3.612 | 83.307 | |

| Item 10 | 0.71 | 0.528 | 3.519 | 86.826 | |

| Item 11 | 0.29 | 0.480 | 3.201 | 90.027 | |

| Item 12 | 0.64 | 0.446 | 2.973 | 93.000 | |

| Item 13 | 0.46 | 0.425 | 2.836 | 95.835 | |

| Item 14 | 0.77 | 0.335 | 2.232 | 98.067 | |

| Item 15 | 0.59 | 0.290 | 1.933 | 100.000 | |

| Model | RMSEA (CI 90%) | sbX2 | SRMR | CFI | NFI | IFI | RFI | AGFI | GFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 items | 0.074 (0.065 - 0.083) | 308.8 | 0.047 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.92 |

Abbreviations: RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, standardized RMR; CFI, comparative fit index; NFI, normed fit index; IFI, incremental fit index; RFI, relative fit index; AGFI, adjusted goodness of fit index; GFI, goodness of fit index.

Table 5 shows the CFA results of the single-factor structure. These findings were considered acceptable as the factor loading of all the items was significant (> 0.45), except for item 11. In the present study, the fit indices of the model included RMSEA (0.074), SRMR (0.047), CFI (0.97), NFI (0.96), IFI (0.97), RFI (0.95), GFI (0.92), and AGFI (0.89). According to the information in Table 5, the factor loading of all the items were significant.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persian MAAS | 1 | |||||||

| DASS-21 (depression) | -0.44 a | 1 | ||||||

| DASS-21 (stress) | -0.49a | 0.52 a | 1 | |||||

| DASS-21 (anxiety) | -0.54 a | 0.61 a | 0.69 b | 1 | ||||

| DASS-21 (total) | -0.58 a | 0.84 a | 0.76 a | 0.73 a | 1 | |||

| Aggression scale | -0.43 a | 0.26 a | 0.38 b | 0.30 a | 0.37 a | 1 | ||

| GSE | 0.41 a | -0.31 a | -0.34 a | -0.34 a | -0.35 a | -0.36 a | 1 | |

| CAMS-R | 0.68 a | -0.41 a | -0.44 b | -0.43a | -0.47 a | -0.33 a | 0.27 a | 1 |

aP < 0.01

bP < 0.05

4.2. Reliability

The internal consistency and reliability of the Persian MAAS were evaluated for Iranian substance abusers based on Cronbach's alpha for all the participants, and the value was estimated at 0.89. The corrected item-total correlation coefficient was above 0.40 (except for item 11) and remained constant at 0.26 (Table 6). Furthermore, temporal stability was assessed using the test-retest method in a small sub-sample of 91 participants over two weeks and calculated to be 0.81 (95% CI = 0.79 - 0.83).

4.3. Validity

According to the information in Table 6, the negative correlation between the Persian MAAS and the three DASS-21 subscales ranged from -0.44 to -0.58, while it was -0.43 for the aggression scale. The convergent validity of the MAAS was also determined by correlating the GSE and quality of mindfulness scores. The positive correlations between the MAAS, GSE (r = 0.41), and CAMS-R (r = 0.68) also indicated good convergent validity (Table 6).

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to validate the Persian version of the MAAS among Iranian substance abusers, and the obtained results were consistent with the previous findings in this regard (21). Accordingly, the MAAS could be used as a valid, reliable tool for measuring mindfulness. Today, mindfulness in addiction could be used to resist temptation. Therefore, mindfulness plays a unique role in preventing relapse (22).

According to the literature (23), the Persian version of the MAAS has a negative correlation with the DASS-21 (total and subscales), signifying that mindful individuals experience less anxiety. This is in line with the studies indicating a negative correlation between mindfulness and neuroticism in various sample populations (7). Consequently, mindfulness could contribute to alleviating anxiety. Similarly, (24), a study showed a negative correlation between mindfulness and anxiety as insufficient attention is the main sign of anxiety and depression. Mindfulness reduces rumination, thereby decreasing the expression of aggression (25). In another research, the MAAS was observed to be correlated with aggression and general self-efficacy. Based on (26), it could be inferred that nonjudgmental attention and awareness of the moment are associated with general self-efficacy.

One of the main limitations of the present study was the lack of predictive validity measurements, and it is suggested that further research address this particular issue. Another suggestion for further research in this regard is to assess the psychometric properties of the Persian MAAS in clinical samples and investigate the application of the scale for behavioral outcomes in the Iranian population with an emphasis on the mindfulness dimension. It is also recommended that more studies be focused on this scale in different addictions (e.g., alcohol and methamphetamine abuse). The intensity of substance abuse and a history of drug abuse should be considered in further investigations as well. The discrepancy in the education level and ethnicity of the participants should also be considered in subsequent studies. Longitudinal and longitudinal-comparative studies could be highly informative in this regard.

5.1. Conclusions

According to the results, the MAAS could be applied as a supplementary tool to assess mindful attention awareness in substance abusers. The validation and adaptation of the MAAS for Iranian substance abusers might be an important step toward identifying specific outcomes of mindfulness, thereby allowing researchers to have a more precise conception of the abilities developed through this modality. In general, the analysis of the behaviors associated with mindfulness among substance abusers is incomplete regardless of the sociocultural context. Therefore, addressing these issues could help these patients promote their health and mindful attention awareness. The MASS could properly assess awareness and attention in Iranian substance abusers.