1. Background

Cancer patients experience a great deal of pain during their illness. People with pain experience a lack of tolerance for cancer and find it difficult to tolerate the situation (1). Pain is a form of stress that reduces a person’s satisfaction with life, resulting in stress, suffering, and discomfort, and impairing the body’s overall function (2). For this reason, pain relief is considered a medical priority after addressing the issue of saving a patient’s life (3). Pain reports are influenced by individuals’ attitudes and beliefs, as well as their sources and methods of coping (4). Cancer can also lead to numerous social and psychological problems (5). The diagnosis and treatment of cancer is a psychological, social, and welfare perspective in addition to the physical aspect (6).

As a result, the factors that make a cancer patient more compatible with their needs and threats are the foundation of this study. Among these, resilience is special in evolutionary psychology, family psychology, and mental health (7). People who are resilient are able to face adversity with higher emotional stability, while maintaining their protective role (8). According to Freiburg et al. (2005), as cited by Momeni and Alikhani (9), resilient people have more flexibility against harmful conditions and protect themselves against these conditions. Resilience is the ability to maintain a bio-psychological balance in dangerous situations (10).

In addition, resilience has been associated with positive emotional, sensational, and cognitive outcomes (11-13). Kumpfer (1999) as cited by Seyed Mahmoudi et al. (14). believed that resilience is a return to the original balance or reaching a higher level of balance in threatening conditions, providing effective adaptation in the individual’s life. Studies have shown that people with high fluctuations have a lower level of avoidance, cope better with pain, and have a relatively catastrophic attitude (15, 16) Psychological consequences of diagnosing the disease have long-term mental and physical effects on the individual (17, 18). In addition, resilience has an inverse and significant relationship with psychological stubbornness, depersonalization, stubbornness and emotional analysis (19), resilience, social support, and mental health (20), metacognitive strategies and creativity (21), optimism (22) and positive and negative emotions and optimism (14). There is a positive and significant between resilience and emotional fatigue, and a negative correlation between depersonalization and personal inadequacy (23). The ability to adapt to difficult situations also plays a crucial role in the later stages of a patient’s life. At all stages of cancer, resilience is determined by previous characteristics such as demographics and individual characteristics (e.g., optimism, social support), adaptation mechanisms such as coping and medical experiences (e.g., positive communication), and psychosocial consequences are like the quality of life and focus on resilience is important to psychological care for patients.

Recently, the Pain Resilience Scale (PRS) was developed and validated in an undergraduate population without clinical pain. The exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses resulted in a 14-item measure comprising ‘behavioral perseverance. This measure captures continued behavioral engagement and motivation despite the pain, and “cognitive/affective positivity”, reflecting the ability to maintain positive and manage negative cognitions and emotions while in pain. The PRS showed moderate to strong positive relationships with other measures of resilience and resilience-related constructs (i.e., self-efficacy, optimism, hope) as well as small to moderate negative associations with commonly used psychosocial vulnerability measures. Measures of general resilience, such as the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), have shown that increased general resilience is associated with lower pain intensity and improved mental health outcomes in chronic pain (24).

The Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (CPAQ) was used to measure chronic pain acceptance as a psychological construct describing one’s ability to focus on valued activities instead of attempting to control or avoid pain (25).

2. Objectives

Several studies have been conducted on the word resilience. However, no research has been conducted on the pain resilience of cancer patients in Iran. This research examines the standardization and validity of this tool due to the importance of this issue and the role resilience plays in the psychological pathology of cancer patients and the pain resilience of these patients, as well as the lack of such tools available. The pain tolerance was measured on cancer patients and its validity and the reliability was determined.

3. Methods

This descriptive correlational study was conducted using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis on the psychometric properties of the Pain Resilience Scale in cancer patients in 2021. The statistical population of this study consisted of all cancer patients referred to the chemotherapy ward of Imam Reza Hospital.

According to the Ankawi et al. (24), the PRS has 14 questions. A 5-point Likert including 0 = none, 1 = very low, 2 = medium, 3 = high, 4 = very high was used to score this scale, consisting two subscales of behavioral perseverance and emotional/cognitive positive thinking. The minimum and maximum score on this scale is 0 and 56, respectively.

The scale was given to four professors of psychology and psychometrics to review the translated scale and provide their opinions in the form of a content validity index to determine the content validity. The scale was then given to 12 patients to express their views on the meaning and concept of the scale’s questions. Different researchers require different numbers of samples to perform factor analysis to determine the validity of the structure. Based on these criteria, 200 samples were finally selected (26). Convenience sampling was used to achieve a sufficient sample size for confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate the validity of the scale structure.

The confirmatory factor analysis method was used to determine the construct validity of the PRS using the Amos statistical program and absolute and comparative fit indices, including NFI, Comparative Fitness Index (CFI), GFI, IFI and root mean square error (RMSEA) (27, 28). Studies have shown that the value of 0.06 to 0.012 is good, 0.06 and less is excellent for RMSEA, and the value of 0.90 and above is preferred for relative indices (29).

4. Results

The items related to the PRS are listed in Box 1.

| Item |

|---|

| When you have chronic or acute pain... |

| I overcome the pain. |

| I am still striving to achieve my goals. |

| I provide the means for success. |

| I try to keep working. |

| I like to stay active. |

| I focus on positive thoughts. |

| I have a positive attitude. |

| It does not affect my happiness. |

| I still enjoy life. |

| I have a hopeful attitude. |

| I will not let it get me down. |

| I will not let it make me anxious. |

| I avoid negative thoughts. |

| I try to relax. |

Table 1 provides information regarding the statistical sample.

| Variable and Class | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 95 (48) |

| Male | 105 (52) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 36 (18) |

| Married | 164 (82) |

| Smoking | |

| None | 167 (84) |

| Cigarettes | 21 (10) |

| Narcotics | 12 (6) |

| Type of disease | |

| Cancer | 111 (56) |

| Other | 89 (44) |

| Duration of illness | |

| Under a year | 121 (60) |

| Two years | 25 (12) |

| Three years | 21 (11) |

| Four years | 11 (6) |

| Five years and higher | 22 (11) |

| Age (y) | |

| Under 40 | 49 (25) |

| 41 - 50 | 44 (22) |

| 51 - 60 | 42 (21) |

| 61 and higher | 65 (32) |

| Level of education | |

| Illiterate | 57 (29) |

| Primary | 33 (16) |

| Guidance | 7 (3) |

| High school | 69 (35) |

| University degree | 34 (17) |

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for behavioral perseverance, emotional/cognitive positivity, and the whole questionnaire were 0.84, 0.93, and 0.94, respectively. In humanities research, an alpha coefficient higher than 0.75 is acceptable (30).

In addition, the correlation between the PRS scores and general resilience of Connor and Davidson through the Split-Half method was 0.541.

The questionnaire can be evaluated using factor analysis to determine whether it measures the desired components. This goal can be achieved with a KMO index of 0.91 and a sufficient number of samples for exploratory factor analysis. In addition, the Bartlett ratio is equal to 1991.18, which is significant with the degree of freedom of 91 and at the level of 0.001. These two factors indicate that the PRS items are suitable for factor analysis.

Principal components and Varimax rotation method were used to determine the percentage of variance explained by each factor. According to this questionnaire, 65% of the variance of the pain resilience variable is explained (Table 2).

| Dimension | Total | Percentage of Variance | Percentage of Compression Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.276 | 37.684 | 37.684 |

| 2 | 3.898 | 27.841 | 65.525 |

Generally, operating loads above 0.71 are excellent, 0.63 are very good, 0.55 is good, 0.45 is appropriate, and 0.32 is weak (Tabachnick and Fidell, as cited by Rolli Salathe et al. (31)). A total of two factors were extracted, and the agent’s name was selected based on the concept in the factor. Table 3 lists the factor loads for each item.

| Item | Component | |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional/Cognitive Positivity | Behavioral Perseverance | |

| 1 | 0.617 | |

| 2 | 0.721 | |

| 3 | 0.737 | |

| 4 | 0.825 | |

| 5 | 0.797 | |

| 6 | 0.647 | |

| 7 | 0.655 | |

| 8 | 0.725 | |

| 9 | 0.738 | |

| 10 | 0.792 | |

| 11 | 0.755 | |

| 12 | 0.809 | |

| 13 | 0.728 | |

| 14 | 0.694 | |

According to Table 3, the operating loads of the items on their components are high, indicating their high correlation and their high validity.

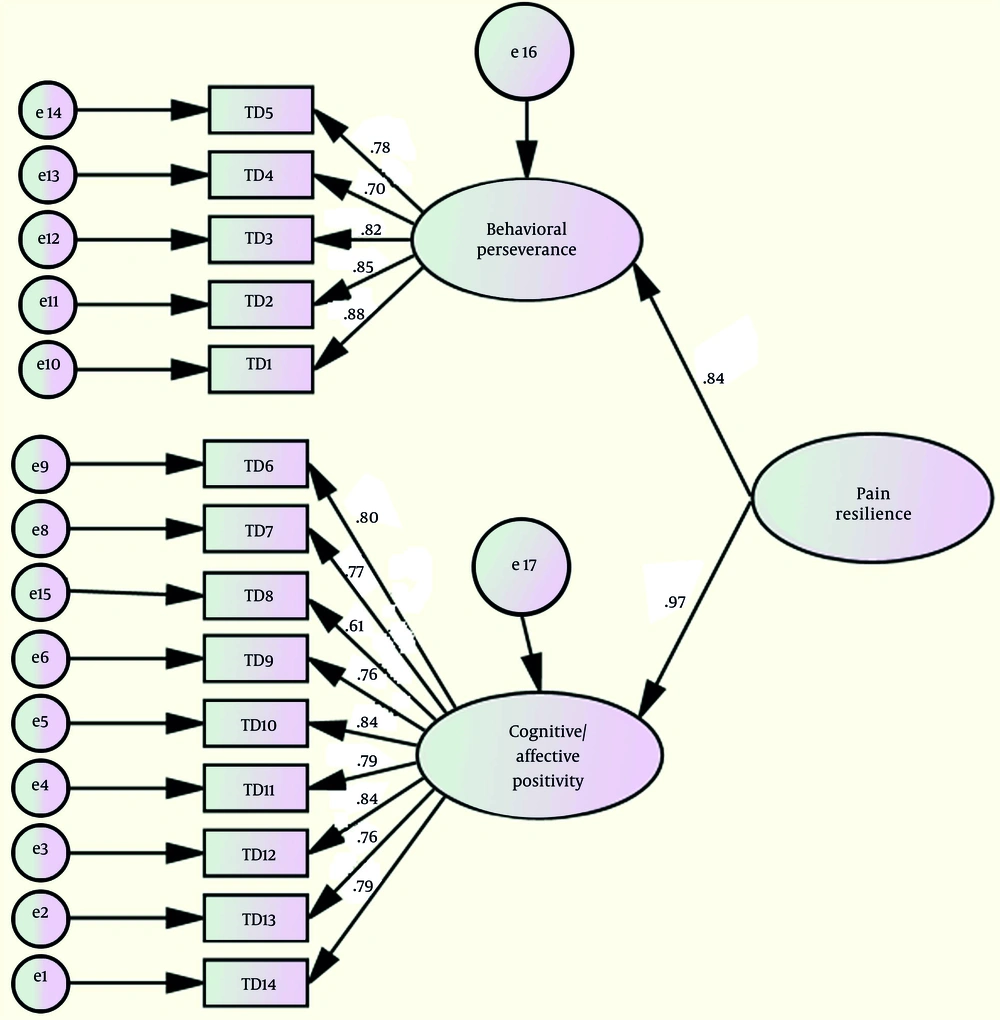

The first step in this study was to plot the questions related to each dimension as the observed variables. Two components were identified through exploratory factor analysis. The behavioral perseverance with five items and emotional/cognitive positivity with nine items were included in the model. The estimates and goodness indicators of the final model fit are shown in Figure 1 and Tables 4 and 5.

| Routes | Standard Coefficients | T | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral perseverance ← pain resilience | 0.84 | 8.124 | 0.001 |

| Emotional/cognitive positivity ← pain resilience | 0.97 | 7.573 | 0.001 |

| Fit Indicators | Root Mean Square Error | Comparative Fitness Index | Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index | IFI | RFI | NFI | χ2/df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptable fit | < 0.10 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | < 3 |

| Computed fit | 0.087 | 0.910 | 0.908 | 0.911 | 0.903 | 0.910 | 2.476 |

Table 5 shows the goodness-of-fit indices for the second-order factor analysis. Chi-square divided by degree of freedom yields a value of 2.48, which indicates a good fit for the model since a value less than 3 indicates a good fit. In addition, the RMSEA for the model is 0.06, which is acceptable for the current model. The AGFI for the model is 0.91, and the CFI is 0.91.

5. Discussion

An evaluation of the validity and reliability of an abbreviated form of PRS in cancer patients was conducted in the present study. First, the PRS was translated into Persian, which was consistent with the English version in translation. The construct validity of the instrument was assessed through both exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. The confirmatory factor analysis results confirmed that the questionnaire structure has an acceptable fit with the data with a favorable factor validity, and all the goodness indicators confirmed the overall model fit for the sample.

Resilience has received increasing attention in other studies of chronic pain such as neck pain, low back pain (32). The resilience of cancer patients is not well researched, despite the fact that they have a lot in common with other chronic pain patients. The confirmatory factor analysis results confirmed that a two-factor model is a sufficient fit for the data. Behavioral perseverance and emotional/cognitive positivity were achieved factors. The behavioral perseverance is about the persistence of behavioral conflict and motivation despite the pain. The emotional/cognitive positivity demonstrates the ability to manage positive and negative emotions and cognitions when in pain. These findings are consistent with previous studies (33).

Based on these preliminary findings, the abbreviated PRS version has good convergent validity for use in cancer patients with pain. One of the limitations of this study was the restricted statistical population of cancer patients. Since all patients were selected from one hospital, our study cannot be generalized. This questionnaire is suggested to be used in a variety of environments and with a variety of accreditation communities in order to ensure its safety. A longitudinal study is necessary to assess the sensitivity and responsiveness of the abbreviated PRS for cancer patients. Therefore, more longitudinal studies are still needed on this tool.

5.1. Conclusions

Results showed that the questionnaire’s reliability and validity coefficients is appropriate, its shortness is convenient, and it can be easily implemented by researchers. Thus, this Scale, which measures pain resilience well, can be used in clinical and research settings and provide a basis for studies in psychology.