1. Background

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the highest incidence of hospital-acquired infection (HAI) (1-3). In addition, hospital-acquired urinary tract infection (HAUTI) is a common problem of critical disease closely related to increased patient morbidity (4) and mortality (5). In addition, HAUTIs are associated with increased hospital stay (5), hospital costs (6), or more significant healthcare expenditures (4) that can be merged into severe infections such as urosepsis and septic shock (7).

This study showed different statistics of UTIs that account for HAIs in the intensive care unit (ICU) (2, 8-11). Generally, 1,879,356 patients were hospitalized in all hospitals with over 200 beds in Iran. The prevalence of HAIs was 0.57% (10557 patients), and UTI was the most prevalent infection (32.2%) (12). Urinary tract infections account for 20 - 50% of all HAIs in the intensive care unit (13). Practically all patients with an HAUTI in the ICUs are accompanied by urinary catheters; other items related to the development of these HAIs include increased time of urinary catheterization, female sexuality, duration of intensive care unit stay, and preceding systemic antimicrobial therapy (4).

Contrary to the findings of some researchers (8, 14), approximately 80% of UTIs are associated with urinary catheters (UCs) (15), and this infection increases in patients who are critically ill (16, 17). In addition, the ratio of HAUTI in ICU is directly associated with the expansion of urinary catheterization (18). The essential reason for this higher prevalence is the use of catheters in patients (19).

The most prevalent HAIs are in critically ill patients (15, 20-22), and HAIs due to urethral catheters cause increased morbidity (4) and mortality rates in patients (18). In addition, 4465 patients were hospitalized 4915 times in three years in ICU for at least 48 hours. In general, 356 ICU-acquired UTIs happened among 290 patients (6.5%), and an overall rate of ICU-acquired UTIs of 9.6 per 1000 ICU days was reported. Antibiotic resistance of pathogenic microorganisms was recognized amongst 14% of isolates (20). The most crucial cause of HAUTI was Escherichia coli, followed by Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, fungal infections, and Enterobacter (50, 17.5, 7.5, 5, and 2.5%, respectively) (23).

In addition, 17 to 69% of infections related to the urinary catheter can be prevented using evidence-based prevention and management (24). Furthermore, the designation of their prevalence and risk factors are the primary agents for preventing HAUTIs (25).

There is limited data on the epidemiology of ICU-acquired UTIs in Iran. Most studies about the prevalence of HAUTI and the suggested preventive strategies are based upon findings from a few countries, basically from Europe and North America. The epidemiology of HAUTIs was evaluated in European and developing countries and used as a tool to define HAUTIs control priorities. Moreover, no epidemiological research (similar) has been performed in the ICU in Kermanshah. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate the prevalence of HAUTIs among patients in the ICU of hospitals under the supervision and affiliated with the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (KUMS). The findings could be compared to international statistics, and challenges in health services can be determined to pave the way for a rational explanation.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine the epidemiology of HAUTIs in the medical intensive care units (ICUs) of hospitals in Kermanshah, Iran.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional and descriptive/analytical study was conducted in the ICUs of hospitals (Taleghani, Imam Khomeini, and Imam Reza Hospitals) in Kermanshah after obtaining permission from KUMS. This research was approved by the Ethical Committee of KUMS (IR.KUMS.REC.1397.977) and conducted from March 2018 to 2019.

The studied hospital wards consisted of ICUs with 256 beds. The statistical population included inpatients who had undergone urethral catheterization. ICU beds were evaluated daily for urinary infections for 12 months.

All patients with various diagnosed diseases from different departments, including internal medicine, renal, neurology, general surgery, gynecological surgery, pregnant women, orthopedics, rheumatology, urology, and infectious diseases, were hospitalized in the general ICU of Imam Reza Hospital. Taleghani Hospital is the largest center of trauma and accidents in western Iran. In addition, medical services at Imam Khomeini Hospital include ophthalmology, otolaryngology, infection, internal medicine, and surgery.

During admission and daily afterward, an infection prevention nurse monitored the patient’s medical documentation throughout the hospital stay. The chief nurses in the wards were also asked to recognize possible HAUTI cases at the start of the research and to report daily probable new cases of infection. All the recognized HAUTIs were recorded in the Iranian National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System, which includes the patients’ demographic characteristics, duration of admission, department, risk factors, and kind of pathogen designed based on the standard questionnaire of the Iranian Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (INIS) of the Center for Communicable Disease Control, Ministry of Health (26). In addition, patient demographic data, laboratory and clinical symptoms of UTIs, and related details were registered on nosocomial UTI checklists with unique laboratory and clinical protocols for HAI diagnosis. The final diagnosis based on these parameters was determined. Symptoms and signs of UTI include fever (increased body temperature equal to or greater than 38°C), urgency of urination or suprapubic tenderness (pelvic pain) with positive urinary culture (CFU/mL ≥ 105) (27), culture, types of antibiotics and antibiogram results were recorded. Antibiogram and culture were conducted based on microbiology (28). The exclusion criterion included all patients with a confirmed diagnosis of fever and UTI symptoms 48 hours before hospitalization (29). Sterile urinary samples were taken from midstream urine (28).

The data were evaluated (if necessary) using the patient documentation based on available data. Statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS software Version 22 using descriptive statistics such as percentages, frequency, and mean, and inferential statistics such as t-tests and chi-square. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all statistical analyses. SPSS statistical software (version 22; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data entry and analysis.

4. Results

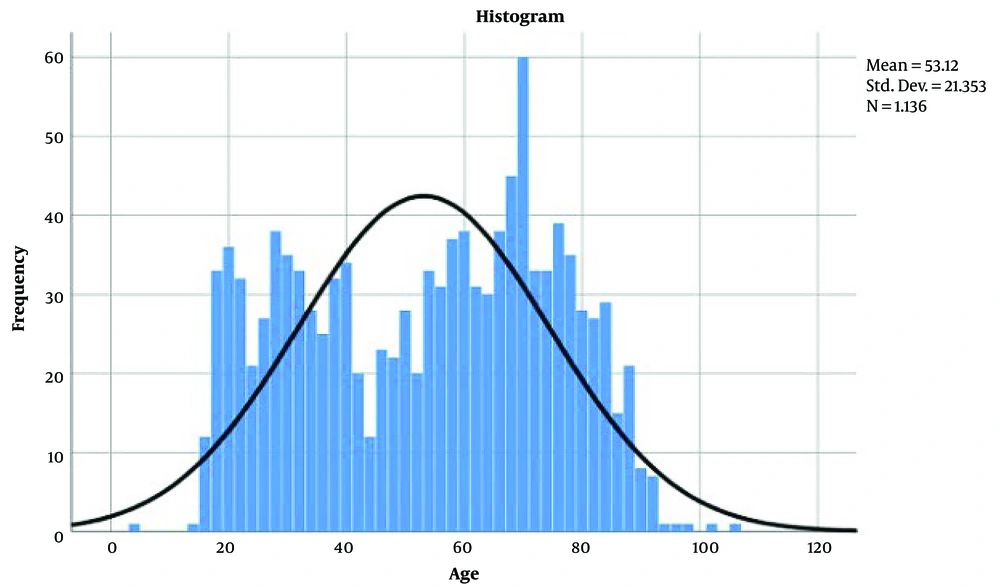

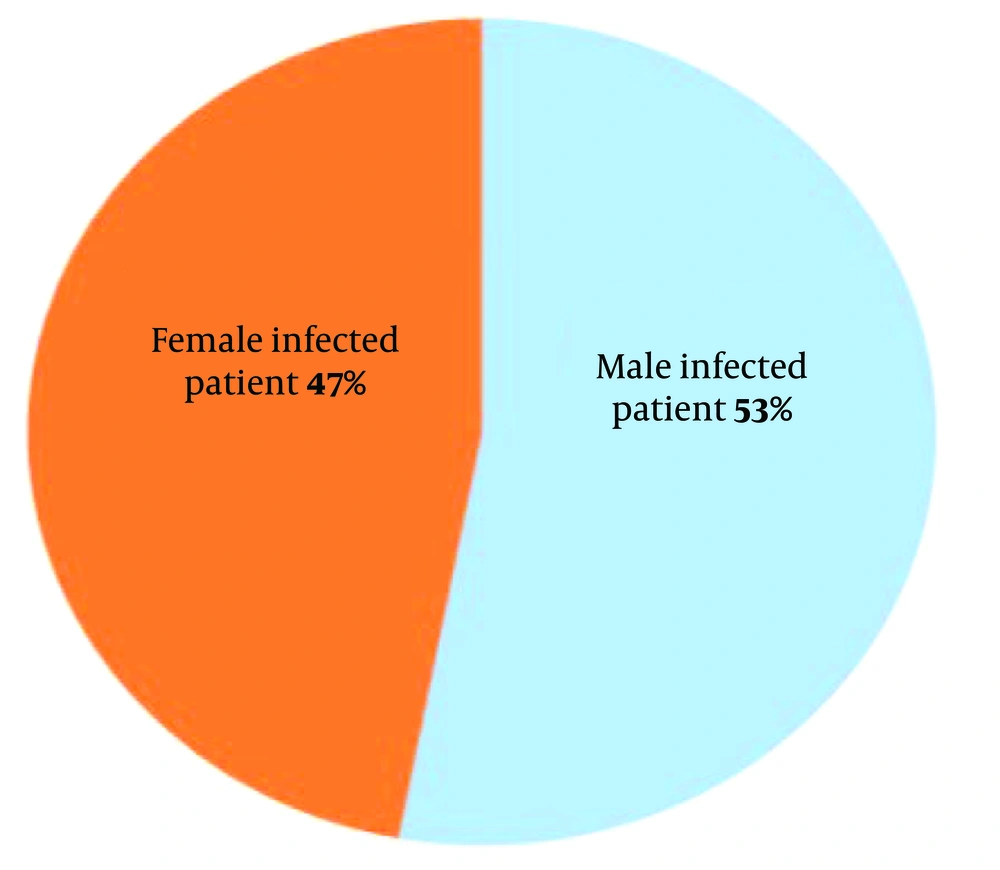

The mean age of the patients was 53.12±21.35 years, and a more significant number were older than 50 (Figure 1). A total of 1136 patients were admitted to the ICUs (Imam Reza and Taleghani Hospitals) during the study period (61 missed of a total of 1197 patients), including 51 found to have UTIs, with an overall HAI rate of approximately 4.5% (Table 1). There were 24 (47%) females and 27 (53%) males (Figure 2).

| Prevalence of HAUTI | Age Groups (Years) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 25 | 26 - 40 | 41 - 55 | > 56 | ||

| Yes | |||||

| Count | 8 | 7 | 8 | 28 | 51 |

| % within infection | 15.7 | 13.7 | 15.7 | 54.9 | 100.0 |

| % within age groups | 5.4 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.5 |

| % of total | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 4.5 |

| No | |||||

| Count | 139 | 234 | 165 | 547 | 1085 |

| % within infection | 12.8 | 21.6 | 15.2 | 50.4 | 100.0 |

| % within age groups | 94.6 | 97.1 | 95.4 | 95.1 | 95.5 |

| % of total | 12.2 | 20.6 | 14.5 | 48.2 | 95.5 |

| Total | |||||

| Count | 147 | 241 | 173 | 575 | 1136 |

| % within infection | 12.9 | 21.2 | 15.2 | 50.6 | 100.0 |

| % within age groups | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| % of total | 12.9 | 21.2 | 15.2 | 50.6 | 100.0 |

In addition, the results showed a significant relationship between sex and HAUTI (P = 0.038) (Figure 2). On the other hand, a significant relationship between age (Table 1), date (different seasons of the year), and HAUTI was not observed (P = 0.588, 0.115, respectively).

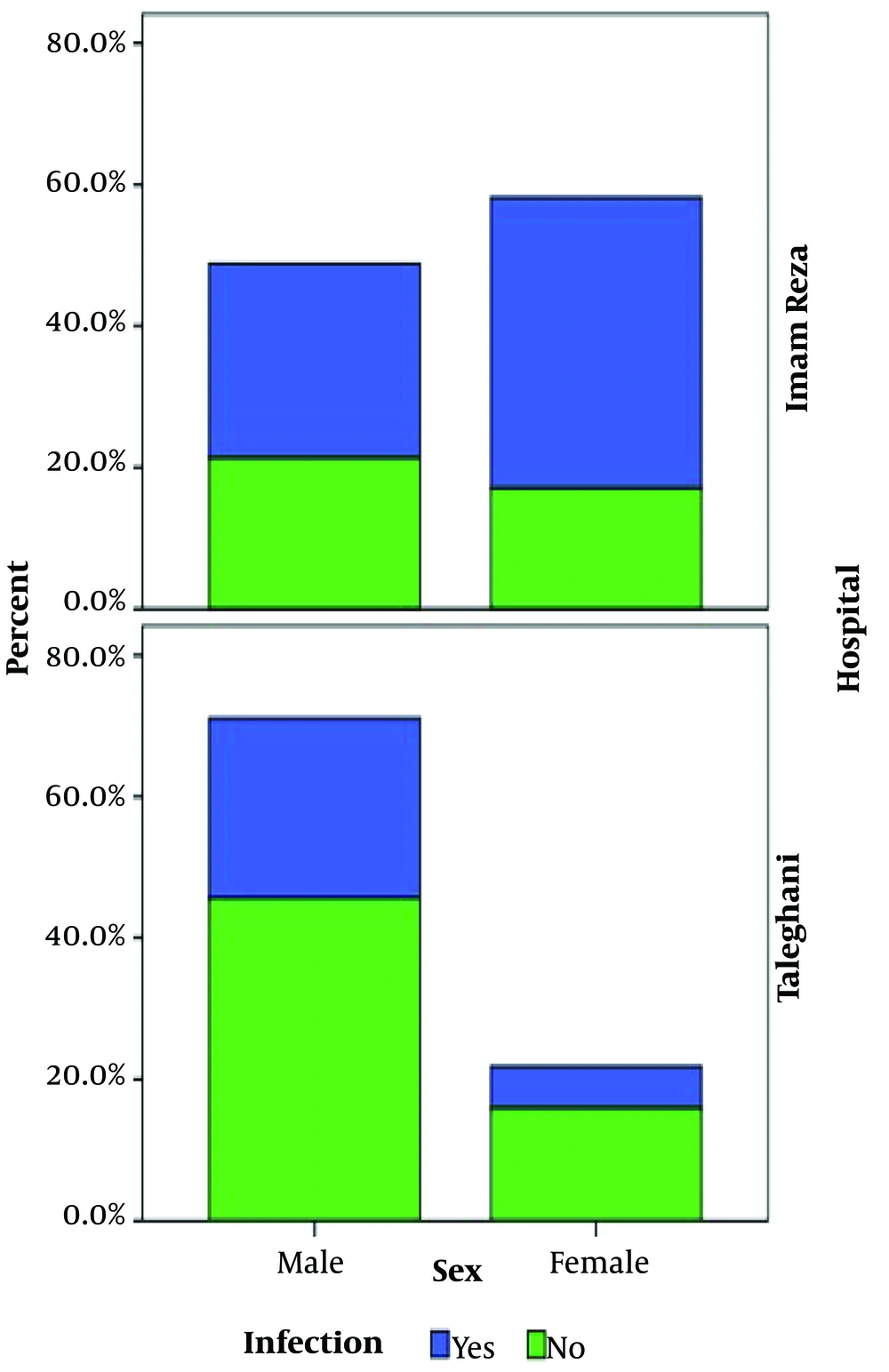

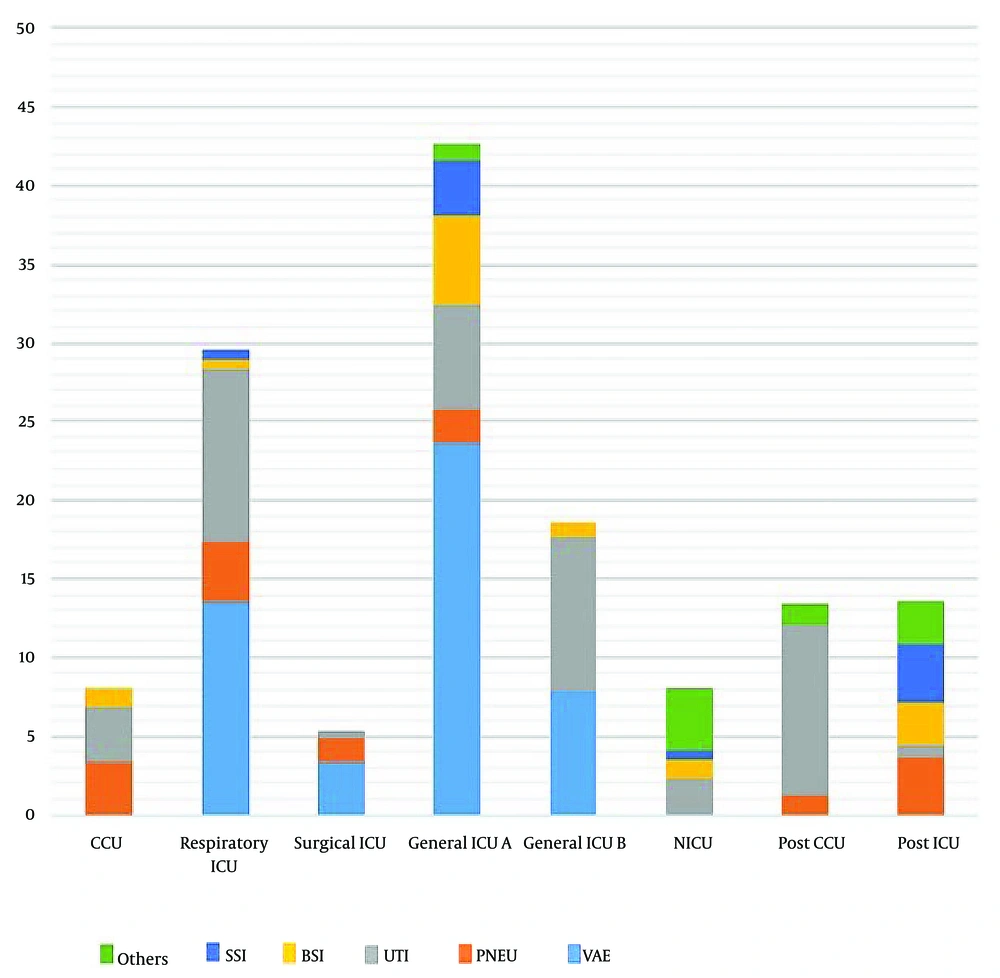

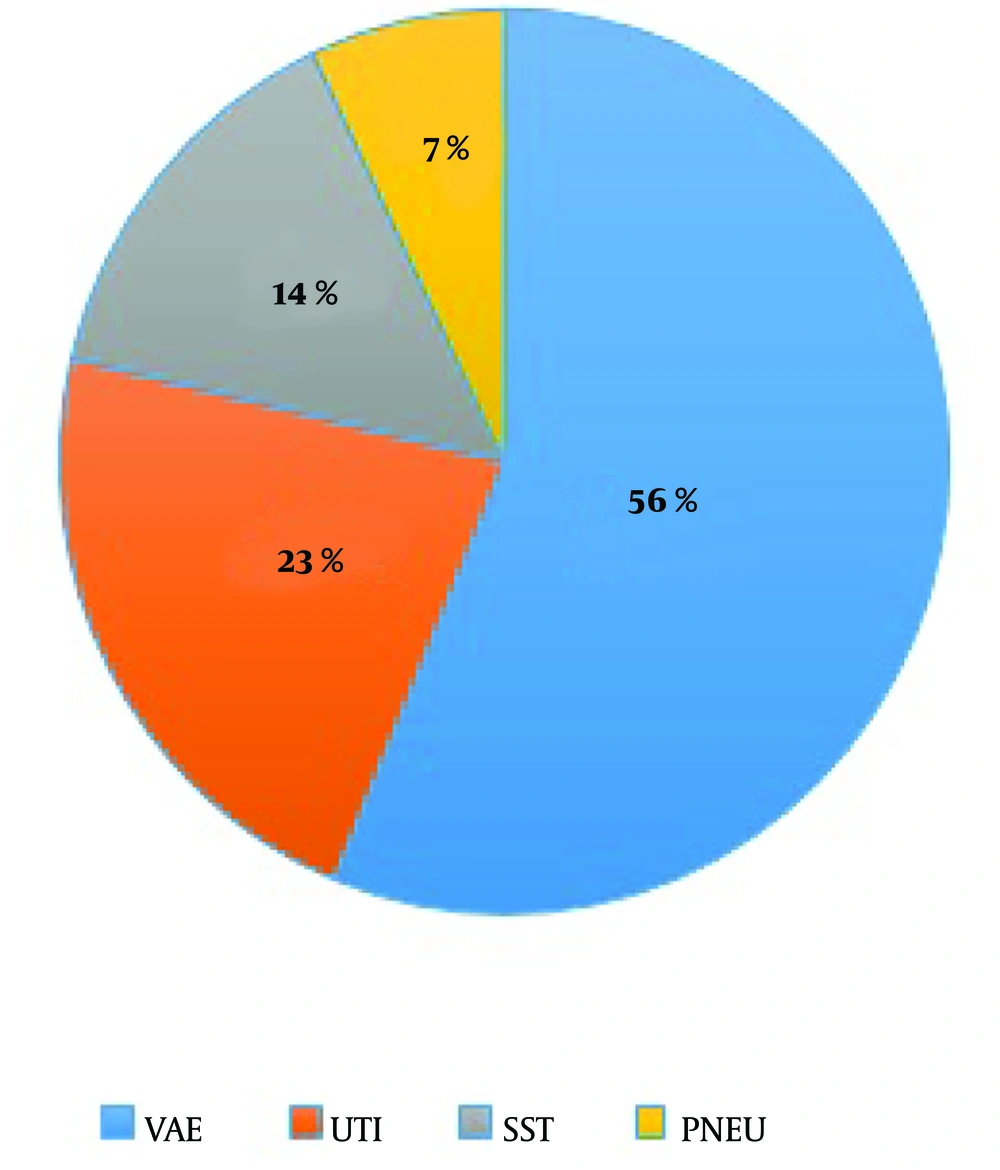

The incidence of HAUTI in Taleghani Hospital was 2.3%, and in Imam Reza Hospital was 7.7%, which was statistically significant (P < 0.001) (Figure 3). In Imam Reza Hospital, the highest incidence of HAUTIs was observed in the respiratory ICU (11%), general ICU B and A (9.6% and 6.7%, separately), and neonatal ICU ward (2.3%), respectively (Table 2). According to INIS, VAE was the most reported infection in the ICUs (24.8%) (Table 3, Figure 4), although in other hospital wards, the most prevalent infections were found to be UTI and Skin and Soft Tissue Infection (SST), representing 15.5 and 13.3%, respectively, of the total infections (Table 3). In addition, the lowest prevalence of all HAIs in ICUs was related to pneumonia (Figure 5).

| Unit/Ward | VAE | PNEU | UTI | BSI | SSI | Others * | Total (NO) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCU | 0 | 5 (3.4) | 5 (3.4) | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 12 | 8.2 |

| Respiratory ICU | 21 (13.5) | 6 (3.9) | 17 (11) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 46 | 29.7 |

| Surgical ICU | 7 (3.4) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 5.4 |

| General ICU A | 21 (23.6) | 2 (2.2) | 6 (6.7) | 5 (5.6) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (1.1) | 38 | 42.7 |

| General ICU B | 9 (8) | 0 | 11 (9.6) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 21 | 18.5 |

| NICU | 0 | 0 | 4 (2.3) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) | 7 (4) | 14 | 8.2 |

| Post CCU | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 8 (10.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 10 | 13.5 |

| Post ICU | 0 | 4 (3.6) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.7) | 4 (3.6) | 3 (2.7) | 15 | 13.8 |

Abbreviations: VAE, ventilator-associated event; PNEU, pneumonia; UTI, urinary tract infection; BSI, bloodstream infection; SSI, surgical site infection; ICU, intensive care unit; CCU, coronary care unit; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit. Others: *Non-ventilator-associated hospital-acquired pneumonia (NV-HAP), gastrointestinal infections, meningitis, other primary bloodstream infections, etc.

| Hospital Ward | N (% of Total) of Hospital-Acquired Infection | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAE | UTI | SST | PNEU | BSI | SSI | EENT | Others | Total | |

| ICU | 103 (24.8) | 41 (9.8) | 25 (13.7) | 13 (3.1) | 7 (3) | 4 (1.7) | – | N/A | 193 |

| CCU | – | 5 (2.1) | – | 5 (2.1) | 2 (0.8) | – | – | – | 12 |

| Surgery | – | 6 (1.4) | N/A | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.8) | 25 (6) | – | – | 34 |

| ENT, ophthalmology | – | – | – | – | – | – | 27 (6.5) | – | 27 |

| Infection diseases | – | 11 (2.6) | 7 (3.8) | 3 (0.7) | – | – | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.7) | 27 |

| Internal medicine | 2(0.4) | 37 (8.9) | 5 (2.7) | 7 (1.6) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | – | 1 (0.4) | 55 |

| Burns unit | – | N/A | 43 (23.6) | – | N/A | – | – | – | 43 |

| Obstetrics and gynecological | – | 5 (2.1) | – | – | 1 (0.4) | 13 (5.5) | – | 1 (0.4) | 20 |

| Total | 105 | 105 | 80 | 29 | 14 | 43 | 28 | 7 | 411 |

Abbreviations: VAE, ventilator-associated event; PNEU, pneumonia; UTI, urinary tract infection; BSI, bloodstream infection; SSI, surgical site infection; SST, skin and soft tissue infection; EENT, eye, ear, nose, throat, or mouth infection; ICU, intensive care unit; CCU, coronary care unit; ENT, ear, nose and throat. others: *Non-ventilator-associated hospital-acquired pneumonia (NV-HAP), gastrointestinal infections, meningitis, other primary bloodstream infections, etc. N/A, not analyzed.

5. Discussion

In this study, the incidence of HAUTIs was investigated among the ICU patients of hospitals affiliated with KUMS. The findings can be measured by other international studies and statistics. In addition, challenges in service provider systems can be recognized by paving the way for reasonable solutions.

According to the findings, the incidence of HAUTIs had an overall HAI rate of approximately 4.5%. This ratio was 15.1% (26) and 9.2 to 28% in other studies performed in Iran (28, 30-32). In studies conducted in other countries, this ratio was 15.7% (8), 8.7% (33), and 3.6% (34). So many variations in the estimated prevalence of HAUTIs in the research that has been performed may result from the performance of the surveillance and control system in other hospitals. However, the high incidence rate of HAUTI demands training programs focused on performance feedback.

In this study, the most common clinical form of HAI in intensive care units in Imam Reza Hospital was Ventilator-Associated Event (12.8%), followed by urinary tract infection (7.7%) (Table 2). Tabatabaei et al. showed the highest number of HAIs (79.6%) were reported from the ICUs, and the most common clinical form of HAI was pneumonia (67.9%), followed by UTI (13.6%) (35). Studies in Iran have shown that the most significant rate of ICU-acquired infections observed in general and internal ICUs, and the infection rate in these two wards were higher than the average national rate. In addition, the most common nosocomial infections in the ICU were VAE (38.6%) and UTI (19.8%, (36)), respectively. Nonetheless, a study reported different results; in their research, the most common hospital-acquired infection was bloodstream infection (BSI, 6.9%), followed by pneumonia (PNEU, 4.3%) and urinary tract infection (3.6%) (34). However, a widespread problem in ICUs is infection, which may be associated with artificial ventilation and other invasive procedures routinely used to treat ICU patients (37).

This study showed that women tend to have more HAUTIs than men (6.3 and 3.6%, respectively). Based on previous studies, the prevalence of HAUTI was higher among women (4, 15, 17), which may be due to various reasons, including differences in the anatomy of males and females and shorter path to the urethra and vagina, which causes infectious agents to have an easier path to the urinary system (28, 38).

No significant relationship was found between age and HAUTI, and Rahimi et al. indicated no significant difference between age and nosocomial UTIs (15). Furthermore, one study showed the rate of UTIs in women decreased with age but increased in older adults (39). In contrast, other studies have revealed an increased prevalence rate of HAUTI with aging (14, 28, 40, 41).

In this study, the prevalence of HAUTI in Taleghani Hospital was lower than in Imam Reza Hospital. A lower HAUTI ratio in Taleghani Hospital was probably the leading cause of the failure to identify and report actual HAI cases. No significant correlation was found based on the incidence of HAUTIs in different seasons of the year. Furthermore, a study conducted in Iran confirmed these results (35). In contrast, Amiri et al. reported different results and showed a significant decrease in infections in summer. This lower prevalence of UTI might be due to weather characteristics and the high temperature of this city. The decreased prevalence of the infection might also be due to the issue selection method, treatment in other hospitals, selection of patients with symptomatic UTI, and social and cultural characteristics of each society (42).

This study had some limitations. First, this study was performed in only one hospital ward (ICU), which does not represent other healthcare settings in the KUMS, and thus, the results cannot be generalized. Second, some samples might have been lost because of the definition of a positive urine culture as bacterial growth of 105 CFU/mL with a single bacterium. In addition, the lack of access to complete information on all patients in Taleghani and Imam Khomeini Hospitals, another one of the limitations of this research, can be considered (Comparison between some data among hospitals was not possible). Finally, the main limitation of the current study was the insufficient data on some of the cases that led to exclude them from the research.

Generally, the findings showed a lesser ratio of HAI, and the most crucial reason is the failure to diagnose, identify, and report actual cases of HAI. Furthermore, the prevalence of reported HAUTIs was relatively low compared with similar investigations, indicating a severe weakness in the surveillance of HAIs for identifying, detecting, and reporting them in hospitals. In other words, under-diagnosis and/or under-reporting of HAUTIs in this situation can be reflected.

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the results, HAIs, especially UTIs, are the types of critical infectious diseases, which need further attention. No single strategy was widely used to prevent HAUTI. There are few studies on HAUTIs mainly acquired in the intensive care unit, and other research is needed to better describe the epidemiology and management of these problems. Promoting identification and reporting systems for controlling and preventing nosocomial infection should be implemented. In addition, the opportunity to improve conditions for expanding any strategy to reduce the prevalence of infections associated with HAUTIs and their outcomes in ICUs is recommended.