1. Background

Physical education teachers and trainers are tasked with imparting movement skills to students accurately and systematically. To achieve this objective, they must employ methods and principles that foster optimal learning within the shortest duration possible. One commonly utilized method for teaching skills is observational learning (OB). Observational learning involves a perceptual process wherein the learner endeavors to imitate skill-related information by observing, receiving, processing, analyzing, and ultimately replicating it (1). In the past, the acquisition and learning of motor skills were believed to stem solely from physical training. However, evidence has indicated a connection between certain physiological-neural processes, action, and observation. This suggests that the representation of modern alone or in conjunction with physical exercise exerts a greater influence on learning movement skills (2).

According to Bandura's theory, also known as the theory of cognitive mediation individuals, after observing a pattern, translate movement-related information into symbolic memory codes. These codes create a mental image in memory, prompting the brain to review and organize the aforementioned information. The memory image serves as a guide for skill implementation and as a criterion for identifying and rectifying errors (3). Bandura delineates observational learning into four stages: Attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation. Additionally, Sally and Newell (4), in their perspective on visual perception, highlight that the human visual system reduces information concerning the situational characteristics of observed actions and directly receives it. Human beings proficiently link perception and action when receiving this information about relative movements, as it is crucial in forming a coordinated pattern. Skill demonstration can occur through live and non-live models; the latter includes video displays, markers, or skeletal displays (5).

Several studies have demonstrated that the utilization of video modeling enhances the learning of skill movements, such as gymnastics (6), tennis serves (7), and weightlifting snatch movements (8). This method allows players to observe correct techniques and analyze them (9). Moreover, it enables the identification and learning from others' mistakes (10).

Numerous studies have explored visual learning and the utilization of live and video demonstrations. Some have examined the impact of observing living and non-living patterns on the acquisition and learning of motor tasks (1), while others have focused on comparing same-age models to the observer and assessing the effect of peer versus non-peer models on motor skill learning rates (11). Over recent decades, researchers have investigated the impact of models' skill levels on skill acquisition. For instance, Andrieux et al (12). Demonstrated that observing both beginner and expert models enhances memory retention over time. Researchers have also compared various methods of video presentation, such as animated models, still images, and combinations, on the acquisition of specific skills (13).

Moreover, Guadagnoli and Lee (14) argue that factors like the nature of the task, practice conditions, and the learner's experience can influence the amount of information extracted from observing live and video models. Researchers have even considered the duration of the demonstration model's presentation and the delay in imitation. For example, Ghandehari Alavijeh et al.'s (15) research focused on the effect of immediate, periodic, and combined imitation exercises on the performance and motor learning of 9-12-year-old kata girl. Their study investigated the acquisition and learning of kata karate under conditions where the movement pattern was immediately repeated after each observation, repeated multiple times post-observation, or a combination of both methods. The results indicated that immediate imitation had a greater impact on skill acquisition and learning. Gender differences in modeling have also been examined by researchers. For instance d'Arripe-Longueville's (16) study comparing same-sex and opposite-sex role models within peer groups revealed gender discrepancies, showing a greater impact in opposite-gender role modeling, affecting the number of training attempts.

Aligned with these inquiries, this research aims to investigate the impact of live and video models of the same and opposite sexes on the acquisition and learning of basketball dribbling and shooting skills. This study seeks to determine whether different role models of opposite sexes affect the learning. Can video modeling of skills have a significant effect on learning and skill acquisition? Which method of demonstration of skills (live or video) is more effective? Is the impact of gender difference greater in live or video pattern?

2. Objectives

As basketball ranks among the most popular team sports globally, requiring intricate technical and tactical skills for success, this comparative analysis endeavors to shed light on the potential role of role models of different sexes in skill acquisition and learning.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects

The present research adopts a semi-experimental design with a repeated measurement approach. The N = 48 voluntary female students aged 13 - 15 years (14 ± 2), assinged to 4 groups of n = 12. observing a live female model (LF), observing a female video model (VF), observing a live male model (LM), and observing a male video model (VM). Prior to commencing the study,all members are beginner and don’t have any experision in dribbling and shooting skill furthermore all volunteers received a consent form.

3.2. Apparatus and Tasks

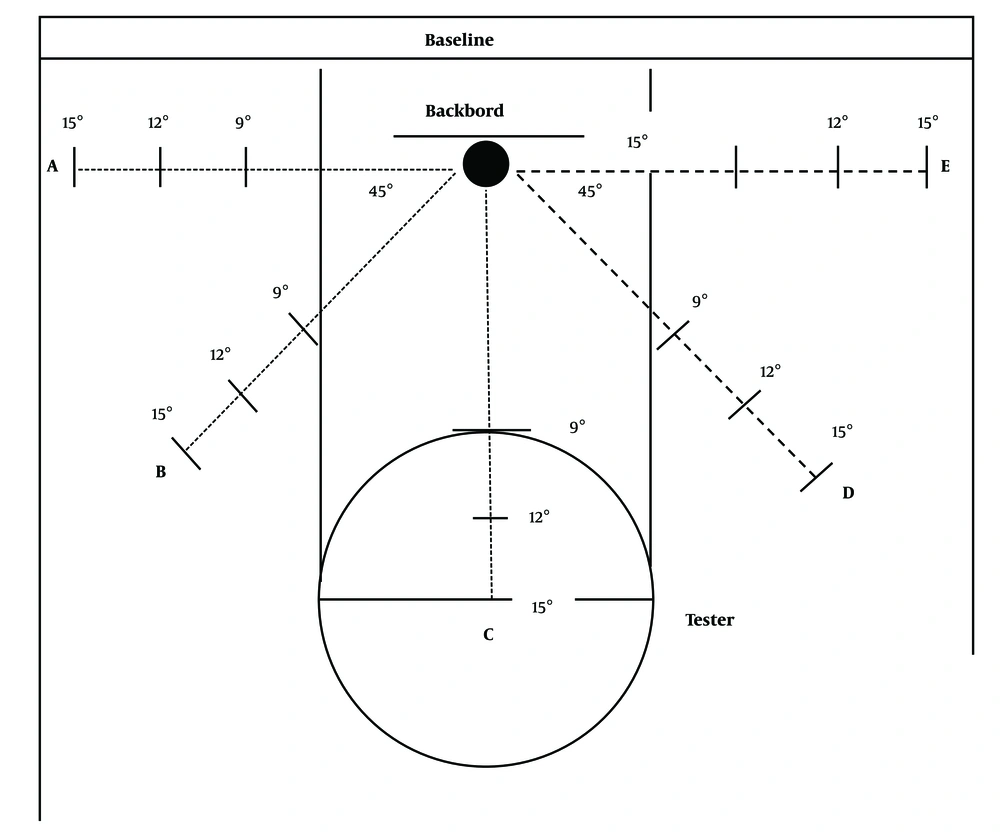

3.2.1. Speed Spot Shooting Test

For the shooting assessment, the subject stands behind the line, throws the ball into the basket, moves under the basket for rebounding, proceeds to the next position, and repeats the sequence. This test is conducted over 60 seconds, awarding two points for a successful basket entry and one point for hitting the top of the ring (Figure 1).

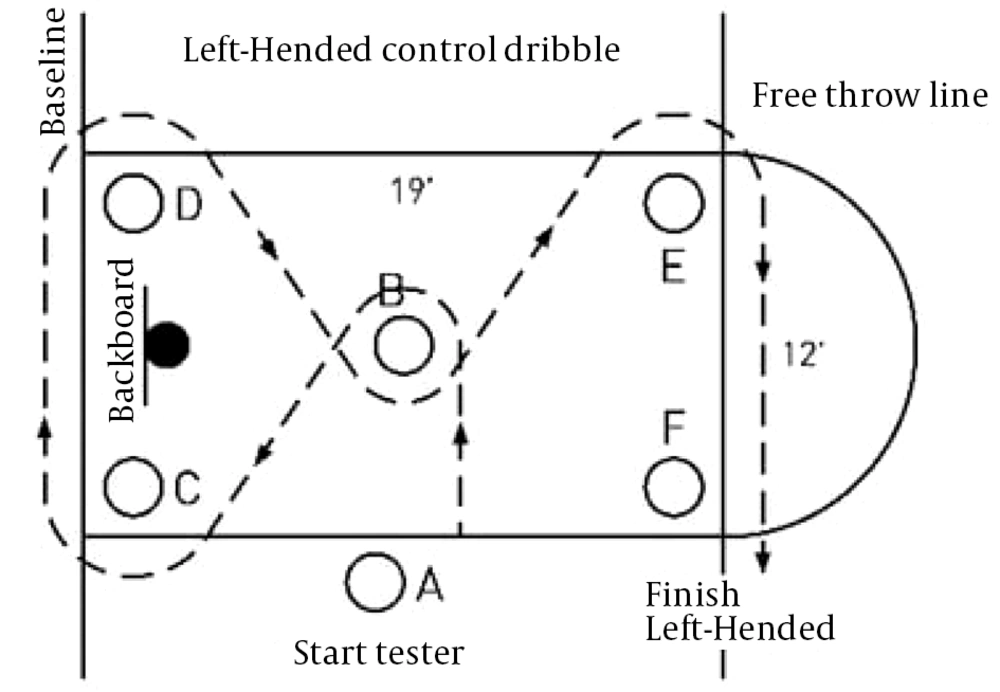

3.2.2. Control Dribble Test (COND)

For dribbling assessment, the subject initiates the test with the non-dominant hand and adjusts hand usage as per the test conditions. Upon crossing the finish line, the timer stops, recording the time to the nearest tenth of a second (Figure 2).

3.3. Procedures

The research unfolds in three phases: Pre-test, post-test, and retention test, aimed at assessing to basketball dribbling speed and the accuracy shooting. In the pre-test, subject were given enough explanations about how to dribble and shoot, and practiced dribbling and shooting skills in ten attempts. In the acquisition phase, we showed live or video models (according to the group in which the people were placed) three times from the front view and three times from the side view to the model, and the members of each group again practiced shooting five times and dribbling twice. After the acquisition phase and the trainees' practice, we entered the post-test phase. During the post-test, subjects repeated the tests. After 24 hours, individuals in each of the four groups underwent a retention test. The duration of dribbling and shot scores were recorded during all three stages—pre-test, post-test, and retention test—and the results across all four groups were compared.

3.4. Data Analysis

To assess the normality of data distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed. The results indicated that all dependent variables across the independent variable levels exhibited a normal distribution throughout all stages of the research (P > 0.05).

Subsequently mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine within-group and between-group effects. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Bonferroni test. All statistical analysis were performed using SPSS 16, with a significance level at P ≤ 0.05.

4. Results

The results of the (4 groups) × (3 times) Mixed ANOVA revealed significant interaction effects of time*groups for both shot and dribble variables (P < 0.05). Additionally, the main effects of group and time on the shot and dribble variables were also significant (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

| Variables and Source | DF | F | Sig. | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shooting | ||||

| Time | 2 | 109.015 | 0.001 | 0.71 |

| Time × group | 6 | 5.881 | 0.001 | 0.19 |

| Group | 3 | 33.412 | 0.001 | 0.70 |

| Dribbling | ||||

| Time | 2 | 48.959 | 0.001 | 0.53 |

| Time × group | 6 | 4.851 | 0.001 | 0.25 |

| Group | 3 | 3.307 | 0.029 | 0.18 |

As the interaction effect proved significant, subsequent pairwase comparisons were conducted using ANOVA with repeated measure for within-group comparisons. The result showed improvements in shooting and dribbling scores from pre-test to post-test and retention across all groups (P ≤ 0.05), except for VF in dribbling (P ≥ 0.05) (Tables 2 and 3).

| Variables and Groups | DF | F | Sig. | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shooting | ||||

| LF | 2 | 23.308 | 0.001 | 0.68 |

| VF | 2 | 16.333 | 0.001 | 0.60 |

| LM | 2 | 676.523 | 0.001 | 0.86 |

| VM | 2 | 17.960 | 0.001 | 0.62 |

| Dribbling | ||||

| LF | 2 | 10.522 | 0.001 | 0.49 |

| VF | 2 | 0.424 | 0.659 | 0.04 |

| LM | 2 | 17.795 | 0.001 | 0.62 |

| VM | 2 | 38.249 | 0.001 | 0.78 |

Abbreviations: LM, Live man; VM, Video man; LF, Live female; VF, Video female.

| Variables and Group | Test 1 | Test 2 | Means Difference (1 - 2) | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shooting | ||||

| LF | Pre-test | Post test | 4.917 | 0.001 |

| Retention | 4.750 | 0.001 | ||

| Post test | Retention | -0.167 | 0.999 | |

| VF | Pre-test | Post test | 2.167 | 0.001 |

| retention | 1.833 | 0.006 | ||

| Post test | Retention | -0.333 | 0.915 | |

| VF | Pre-test | Post test | 6.000 | 0.001 |

| Retention | 5.500 | 0.001 | ||

| Post test | Retention | -0.500 | 0.418 | |

| VM | Pre-test | Post test | 2.750 | 0.001 |

| Retention | 2.583 | 0.001 | ||

| Post test | Retention | 0.167 | 0.999 | |

| Dribbleing | ||||

| VF | Pre-test | Post test | -8.000 | 0.013 |

| Retention | -6.583 | 0.031 | ||

| Post test | Retention | 1.417 | 0.452 | |

| VF | Pre-test | Post test | -1.167 | 0.999 |

| Retention | -0.833 | 0.999 | ||

| Post test | Retention | 0.333 | 0.999 | |

| LM | Pre-test | Post test | -12.500 | 0.003 |

| Retention | -11.650 | 0.006 | ||

| Post test | Retention | 0.950 | 0.076 | |

| VM | Pre-test | Post test | -9.667 | 0.001 |

| Retention | -9.167 | 0.001 | ||

| Post test | Retention | 0.500 | 0.418 | |

Abbreviations: LM, Live man; VM, Video man; LF, Live female; VF, Video female.

The results of Bonferroni's post hoc test showed that, in post test and retention of shooting, the LM group compared to the VM group (P < 0.001), the LF group (P = 0.002 post, P = 0.007 retention) and the VF group (P < 0.001) was better. Also, the average shot scores of the LF group were better than the female vVF deo group (P < 0.001) and the VM group (P = 0.041 post, P = 0.045 retention). However, no significant difference was observed between VM and VF groups at the post-test and retention. The results showed that in the post-test and retention of dribbling performance, the LM group compared to the VM group (P = 0.005 post, P = 0.017 retention), the LF group (P = 0.024 post, P = 0.025 retention) and the VF group (P < 0.001) was better, but no significant difference was observed between other groups (Table 4).

| Variables and Phase | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|

| Shooting | ||

| Pre test | 2.291 | 0.091 |

| Post test | 29.443 | 0.001 |

| retention | 27.000 | 0.001 |

| Dribbling | ||

| Pre test | 0.939 | 0.430 |

| Post test | 8.238 | 0.001 |

| retention | 6.597 | 0.001 |

5. Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare the impact of observing live and video models of both genders on basketball dribbling and shooting skills in girls aged 13 to 15. The general results of this research showed that observing a live male model had the most positive effect on learning basketball shooting and dribbling skills compared to other groups. It also showed that live models (male and female) had a greater impact on the acquisition and learning of these skills than video models, and lastly, there was no significant difference between watching video models (male and female).

Spesiphically, observing LM had a higher performance The findings of this research revealed that, overall, observing male live models had a superior impact on both basketball dribbling and shooting skills compared to other groups. This outcome aligns with d'Arripe-Longueville et al.'s (16) research, suggesting that observing models of the opposite sex triggers the limbic system, leading to increased release of hormones like epinephrine and norepinephrine, thereby enhancing performance. Similarly, Pastore et al. (17). Observed greater benefits in a group exposed to heterogeneous rehabilitation exercise models for stroke recovery. However, Meaney et al.'s (18) study, reported that ten-year-old girls showed better learning outcomes when observing a same-gender (female) model compared to an opposite-sex (male) model. This disparity might be attributed to the age of the participants, who may not have reached puberty and hence might not have been influenced significantly by the opposite sex.

Moreover, the study indicated that live models (both male and female) outperformed video models, consistent with Harrison et al.'s (19) investigation into the impact of two models of tactical demonstration on volleyball skill development. Ross et al. (20) also suggested that OB contributes to a cognitive representation of skill. However, this finding contradicts Maleki et al.'s (21) research, where no significant difference was noted between observing a live model and an animated model.

Another notable point is that presenting male and female video models did not yield a significant difference in skill acquisition and retention. This finding contrasts with studies such as Tannoubi et al.'s (22) research on video exposure's impact on basketball skill development in novice players, Trabelsi et al.'s (23) study on video modeling examples as effective tools for self-regulated learning in physical education , and Souissi et al.'s (8) investigation into self-monitoring video feedback in weightlifting. Additionally, Trabelsi et al. (23) work suggested that repeated viewing of a video model activated various learning and metacognitive strategies, even without direct instruction. One potential reason for our differing results might be the limited duration of skill demonstration in our study, as compared to other research where subjects were exposed to video modeling for longer durations. Magill highlighted that effective OB requires sufficient time for subjects to familiarize themselves with the skill demonstration. He suggests considering task difficulty as a variable during exercises (24).

5.1. Conclusions

We conclude from this research that it is better to use live models to teach skills to beginners. for our subject who are in puberty and are affected by the limbic system, the opposite sex pattern leads to more attention and effort, and as a result, better learning.