1. Background

The cesarean section rate has increased in Iran, and its complications have been one of the concerns of the healthcare system authorities in recent years. Various policies and programs have been taken into account to reduce this rate. One of the health system transformation plans is the promotion of physiological childbirth, which was implemented by the Iran Ministry of Health and Medical Education in 2014 (1). According to this plan, all hospitals should reduce the cesarean section rate by 10% at the end of each year (2). The promotion of physiological childbirth faces many challenges and barriers in Iran (3). Several factors, such as culture, perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, and the values of the couples toward physiological childbirth, are influential in selecting the delivery mode (4). Focusing on the father’s role in the birth process has grown in the last century (5). At present, husbands’ involvement is an important strategy to achieve the development goals of the third millennium, such as women’s empowerment, gender equality, and improvement of maternal health. Accordingly, the World Health Organization recommends husbands’ involvement in safe motherhood programs, which include facilitating the access and use of perinatal care, increasing knowledge about it, and participating in planning for childbirth (6).

Husbands’ involvement is defined as taking roles and responsibilities in the field of reproductive health and supporting their wives to successfully cope with the difficulties of their sexual and reproductive life (7). The rate of husbands’ involvement in reproductive health programs has been reported in some studies. In a study in El Salvador, over 90% of men participated in pregnancy care or during childbirth (8). The results of two studies in Iran revealed that most women were interested in the presence of their husbands during childbirth. However, their husbands’ presence is not customary, and they have a poor role in reproductive health programs (9, 10). The results of a study showed that husbands desired to be actively involved in the antenatal and intrapartum periods; however, they cited several barriers that impeded their involvement. These barriers included the levels of informational support, attitudes toward involvement, qualities of marital relationships, relationships with their own parents, and sociodemographic factors (11).

A study in Canada showed that continuously supporting women during childbirth can boost the rate of vaginal birth, shorten the labor stages, reduce the cesarean section rate, and mitigate the negative feelings of childbirth experience (12). In addition, other benefits of husbands’ involvement in childbirth include strengthening family relationships, increasing the quality of the relationship between husbands and wives, successful breastfeeding, improving gaining weight of premature neonates, and continuing husbands’ healthy behaviors during pregnancy, such as quitting smoking (13). However, husbands’ involvement in pregnancy is also a controversial issue because the mere presence of husbands in prenatal care training courses does not increase their support and involvement. Changing husbands’ views and attitudes requires extensive planning and active involvement of husbands in various pregnancy and childbirth health programs (9). A systematic review study emphasized the need for further studies regarding husbands’ involvement in their wives’ pregnancy issues (14). It is required to perform studies about continuous support during childbirth to focus on long-term outcomes, such as breastfeeding, mother-neonate interactions, postpartum depression, self-esteem, and motherhood problems (12).

Accordingly, international organizations emphasize facilitating husbands’ involvement; however, favorable conditions for active participation in this field have not been provided (15). Qualitative studies can provide a unique insight into the phenomenon of physiological childbirth (3). Qualitative research is suitable for working out individuals’ perceptions and their following outcomes. This type of research reflects more on the phenomena than quantitative studies (16). Due to the effect of cultural factors on husbands’ participation, further studies are needed in different communities.

2. Objectives

This study was conducted to explore husbands’ viewpoints about barriers against their active participation in their wives’ physiological childbirth due to the lack of such studies in Mazandaran province, Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Type of Research and Study Setting

This was a qualitative study using a conventional content analysis method approved by the Deputy of Research and Technology of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. The data were collected until saturation from 13 participants in 2021. The main goal of the research was to provide new knowledge about the husbands’ views on barriers against their active participation in their wives’ physiological childbirth. The research environment included the educational hospitals affiliated with Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences in Sari. The research population included husbands whose wives had physiological childbirth in the aforementioned hospitals. The participants were selected based on the research objective. The inclusion criteria for the husbands were their wives having experience of physiological childbirth during the past 6 months, having a legal marriage relationship, having intended pregnancy of their wives, and having the ability to express their experiences. The exclusion criterion was the unwillingness to cooperate in the study. To ensure maximum diversity, the participants were selected in terms of age, education, job, and the wife’s number of parity.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

For data collection, in-depth interviews with semi-structured open questions were employed. The participants were interviewed individually. At first, the phone numbers of the husbands of the pregnant women who had physiological childbirth in the educational hospitals of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences were extracted by referring to women’s medical records in the Department of Medical Records of the hospital. Then, by contacting the participants and explaining the research objectives, their consent was obtained to participate in the study. Through prior coordination with the participants, the time of the interview was set. The interviews took 30 - 60 minutes in a private room in the aforementioned hospitals. The interview started with a general open-ended question. The individuals’ responses guided the interview process to explore the participants’ experiences.

The interview questions were as follows:

- Considering that your wife had a physiological birth, please tell me about your views in this regard.

- How did your wife’s physiological childbirth process seem to you?

- How did you feel about taking part in this procedure?

In order to clarify the concept and deepen the interview process, the follow-up and exploratory questions were asked based on the data provided by the participants. All the interviews were recorded using a digital recorder. The interviews were listened to several times, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed.

3.3. Data Analysis Method

The data were analyzed comparatively using the conventional qualitative content analysis method using MAXQDA software (version 2020). The content from the qualitative approach of Granheim and Lundman was analyzed through the following stages (16):

(1) Transcribing the interviews and reading them repeatedly to come up with comprehensive knowledge,

(2) Considering all the interviews as a unit of analysis (i.e., the statements supposed to be analyzed and coded),

(3) Considering paragraphs, sentences, and/or words as semantic units (semantic unit as a set of words and sentences related to each other in terms of content was summarized and put next to each other according to their content and meaning),

(4) Abstracting and conceptualizing semantic units according to their hidden meaning and naming them using the codes,

(5) Comparing the codes in terms of their similarities and differences and classifying more abstract categories using specific labels,

(6) Comparing the categories to each other, reflecting on them deeply and thoroughly, and introducing the data’s hidden content under the study theme (16).

Then, to understand the interview content, the entire interview text was read several times, and then the codes in the written texts were determined and extracted by the first authors. Afterward, these codes were explained into subcategories and categories by the first and second authors and reviewed by five participants and four maternal health experts to reach an agreement. Sampling continued until the data reached saturation, in which no new data were extracted from the last interview.

3.4. Research Rigor

The Lincoln et al. rigor four criteria in qualitative research were used to ensure the study’s validity and reliability (17).

(1) Credibility: The validity of this study included the long-term involvement in the data analysis process.

(2) Conformability: The findings were confirmed by the participants. At the end of the analysis, the data were given to five participants who were asked to determine whether the extracted categories represented their experiences.

(3) Dependability: The dependability was assured by reviewing and analyzing the data by the researcher and four maternal health experts. The researcher tried to guarantee the verifiability of this study by confirming all stages of the research with the maternal health experts.

(4) Transferability: Transferability of the data included trying to provide a detailed description of the study report and its applicability in other fields. Table 1 shows a sample of coding and the process of data analysis.

| Category | Subcategory | Open Codes | Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociocultural barriers | Parturient’s shame | Embarrassed seeing her husband in the labor room | “My wife was embarrassed seeing me in the labor room during childbirth, although my wife was very brave and mentally prepared for physiological birth.” (Participant No. 1) |

A Sample of the Participants’ Quotation and Process of Coding and Extraction of Categories and Subcategories

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: REC.MAZUMS.1293). The researcher introduced herself to the participants and explained the research objectives. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study subjects were assured that the interviews would be completely confidential, the recorded voice would be kept in a safe place, and their names would not be disclosed. Additionally, the participants were told they were free to quit the study at any stage.

4. Results

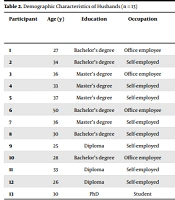

The participants in this qualitative study were 13 husbands whose wives had physiological childbirth. The participants’ age ranged from 25 to 50 years. The participants’ education varied from diploma to PhD. Most of the husbands did not have a history of participating in physiological childbirth preparation courses. However, two husbands attended one session of the course (Table 2). Analyzing the data revealed 485 codes. The codes were classified based on their similarities and differences to show the barriers. Finally, 3 categories and 12 subcategories were extracted (Table 3).

| Participant | Age (y) | Education | Occupation | History of Husbands’ Participation in the Childbirth Preparation Course | History of Presence Along with Delivering Wife | Number of Wife’s Parity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 | Bachelor’s degree | Office employee | No | No | 1 |

| 2 | 34 | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed | One session | No | 1 |

| 3 | 36 | Master’s degree | Office employee | No | No | 2 |

| 4 | 33 | Master’s degree | Self-employed | No | No | 1 |

| 5 | 37 | Master’s degree | Self-employed | No | No | 1 |

| 6 | 50 | Bachelor’s degree | Office employee | No | No | 1 |

| 7 | 36 | Master’s degree | Self-employed | No | No | 1 |

| 8 | 30 | Bachelor’s degree | Self-employed | No | No | 1 |

| 9 | 25 | Diploma | Self-employed | No | No | 1 |

| 10 | 28 | Bachelor’s degree | Office employee | One session | No | 1 |

| 11 | 33 | Diploma | Self-employed | No | No | 2 |

| 12 | 26 | Diploma | Self-employed | No | No | 1 |

| 13 | 30 | PhD | Student | No | No | 1 |

Demographic Characteristics of Husbands (n = 13)

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Sociocultural barriers | Uncommon husband’s presence; Parturient’s shame; Established female caregiving role; Husband’s shyness; Scorn by others |

| Structural barriers | Imperfect maternity ward physical structure; Words and actions contradiction; Non-acceptance of the husband |

| Individual barriers | Occupational problems; Lack of information; Psychological unpreparedness; Fear of harming the mother and neonate |

Categories and Subcategories of Physiological Childbirth Program Barriers Based on Husbands’ Experience

4.1. Sociocultural Barriers

This category included four subcategories of uncommon husband’s presence, parturient’s shame, established female caregiving role, husband’s shyness, and scorn by others.

4.1.1. Uncommon Husband’s Presence

Most participants stated that it is not customary for them as men to be with their wives during childbirth, and this is not accepted in society. In this regard, one of the participants stated:

“It is not common for a man to go to the delivery room in the maternity ward where all individuals are women, and it is not appropriate for our culture for a man to be next to his wife during labor. What kind of mode is it? Where does it come from?” (Participant No. 12)

4.1.2. Parturient’s Shame

Some participants stated that their presence during labor would lead to shame for their wives due to the potential events and their wives’ unwillingness to express their weakness and pain of childbirth and the desire to be free and not tolerate it. One of the participants said:

“My wife was embarrassed seeing me in the labor room during childbirth, although my wife was very brave and mentally prepared for physiological birth.” (Participant No. 1)

4.1.3. Established Female Caregiving Role

Most participants stated that the role of taking care of a parturient during childbirth is a female role, and women have the main role in this case. In this regard, two husbands said:

“My mother-in-law was present during the delivery, and I was at ease.” (Participant No. 6)

“My wife agreed to have a female attendant in the maternity wards; however, this is right in my mind; I am a man, so there is nothing I can do to help.” (Participant No. 9)

4.1.4. Husband’s Shyness

As the participants assumed, they felt more embarrassed and ashamed to be in women-bound environments, such as the maternity wards. The husband of one of the parturient said:

“I went to the birth preparation course due to my wife insisting on it. There were plenty of individuals there, and I did not raise my head out of shame to ask any question.” (Participant No. 5)

4.1.5. Scorn by Others

Most participants indicated that their involvement in taking care of their wives during childbirth causes them to be scorned by those around them. In this case, an interviewee said:

“To be frank, I wanted to be there when my neonate was born; however, I feared to be blamed by those around me, such as my father and brothers.” (Participant No. 12)

Moreover, another man stated:

“When my relatives are guests at my home, I do not help my wife with the house chores in their presence because I am afraid that they will label me as a henpecked (said laughing).” (Participant No. 11)

4.2. Structural Barriers

This category encompassed the subcategories of imperfect maternity ward physical structure, words and actions contradiction, and non-acceptance of the husband.

4.2.1. Imperfect Maternity Ward Physical Structure

As claimed by the participants, the structure of the maternity wards was not the way a husband could be present. One of the participants expressed:

“In that hospital (the name of a public hospital), even my wife’s mother was not allowed to enter the maternity ward, let alone me.” (Participant No. 7)

Another participant said:

“I was keen to be with my wife; however, unfortunately, it was not possible for me to attend the maternity ward. The public hospitals are very crowded, and nobody takes trouble responding to you. I have witnessed several times that I asked about my patient, and no one responded.” (Participant No. 10)

Regarding this matter, another husband said:

“Do you know any place in Iran where the husband can be with his wife during labor? I have not heard of any.” (Participant No. 5)

4.2.2. Words and Actions Contradiction

The participants stated that although the contents were explained in the physiologic childbirth training sessions for pregnant women, the support programs were implemented very poorly, which is due to a lack of proper conditions in the maternity wards. In this regard, one of the participants said:

“During the courses, they told my wife that she could have an attendant; however, when I got to the maternity ward, they did not allow me to enter because it was forbidden to get into the maternity ward as a companion.” (Participant No. 9)

Another participant said:

“Theoretical training in the preparation courses for physiological childbirth, such as the methods for relieving the childbirth pain and allowing a parturient’ companion entering the ward, was not implemented.” (Participant No. 7)

Another husband stated:

“My wife believed in physiological childbirth and somewhat convinced me to take part in childbirth preparation courses; however, unfortunately, the due conditions were not prepared for my involvement in this course by the hospital (referring to one of the city’s public maternity hospitals).” (Participant No. 9)

4.2.3. Non-acceptance of the Husband

As expressed by most participants, the proper setting has not yet been built in Iran for accepting the husband as an effective companion for the parturient in the maternity wards. In this regard, a participant said:

“We as men do not know what to do; they do not even allow us to enter the maternity ward.” (Participant No. 13)

4.3. Individual Barriers

This category included the subcategories of occupational problems, lack of information, psychological unpreparedness, and fear of harming the mother and neonate, which were experienced by all husbands in this study in different ways.

4.3.1. Occupational Problems

The participants said that it is not possible for them to attend childbirth preparation courses because their working hours interfere with the time of the training courses. One of the participants mentioned:

“I do not have time off; I work as a contract employee, and I cannot attend these training courses.” (Participant No. 1)

“I am very busy at work because the cost of living is high.” (Participant No. 9)

“I was invited to attend a course; however, I could not make it due to my working conditions.” (Participant No. 2)

“I was keen to be the first one to see my son; however, sadly, due to working conditions, I missed experiencing this feeling.” (Participant No. 13)

4.3.2. Lack of Information

As expressed by the participants, they lack information about reproductive health issues. One of the participants said:

“I had no idea what to do; there was no defined role for me, and I was useless; however, my wife did not want me to leave her alone.” (Participant No. 3)

4.3.3. Psychological Unpreparedness

The majority of the participants stated that they were not psychologically prepared to participate in the birth process and that they might not solve the problem; rather, their presence might cause a new problem. A husband said:

“Practically, I had no role, and I did not know what to do. I do not think I could tolerate the conditions of my wife’s labor at all.” (Participant No. 3)

Another participant also expressed:

“When entering a hospital, the sight of blood makes me sick. I have no control over this. I have been like this since childhood. I got terrified when my wife’s labor pains started. Generally, I cannot handle my stress.” (Participant No. 6)

4.3.4. Fear of Harming Mother and Neonate

Most participants were worried about childbirth trauma for the neonates and the mother. One of the participants said:

“I heard a lot that the complications of physiological childbirth persist in women, and this is not good at all.” (Participant No. 4)

About the post-physiological labor complications, another participant said:

“I heard that women suffer from backache after physiological childbirth and even need gynecological surgery.” (Participant No. 3)

Referring to the complications of physiological childbirth, a participant said:

“My wife and I were concerned about our neonate getting harmed during physiological childbirth because they said the neonate was big.” (Participant No. 12)

5. Discussion

The current study was carried out to explore husbands’ experience of barriers against active involvement in the physiological childbirth process. In this study, 3 categories and 12 subcategories were developed. One of the categories of this qualitative study was sociocultural barriers. A descriptive and analytical study in Saudi Arabia demonstrated that the presence of husbands in the delivery room is not common due to sociocultural stereotypes in this country (18). The findings of a qualitative study in Gambia showed that husbands did not participate in their wives’ reproductive health issues due to sociocultural and gender-related beliefs rooted in the country’s ancient culture. Feeling ashamed and fear of humiliation was the most critical barrier observed in this study (19). Moreover, in a study in Nepal, some factors, such as limited knowledge, social stigma, shyness/embarrassment, and job responsibilities, were considered the most outstanding barriers to husbands’ involvement in wives’ health issues (20). Additionally, research results in Nigeria reported that husbands’ religious misconceptions and poor education were the important reasons for males’ non-involvement (21).

In a study conducted in Iran, major reasons for husbands’ non-involvement from wives’ viewpoints were cultural factors (e.g., social stigmas, pride, false beliefs, family upbringing, and restrictive customs of small cities), knowledge obstacles, the feminine environment of the health centers, unpleasant behaviors of the personnel, the woman’s reliance on her family, and the family’s financial problems. A lack of attention to culture has been considered of the key weaknesses and barriers to the guidelines to promote physiological childbirth (9).

The findings of the present study revealed that the husbands were not psychologically prepared to actively participate in the childbirth of their wives. On the other hand, wives also did not like their husbands to be present during childbirth. Research results in Iran reported that the husbands’ involvement during childbirth was at an acceptable level (6). This difference can be due to the various definition of husbands’ involvement.

Industrialized countries have a positive outlook on the active and effective presence of husbands during pregnancy and their role in mother and child health-related issues (22). A study conducted at Guilan University, Rasht, Iran, reported the positive attitude of the majority of couples toward the husband’s attendance during childbirth. The increase in the couple’s attitude toward attendance and participation during childbirth was directly related to the education of the couples (23).

Study results in Nigeria showed no statistically significant difference in the couples’ interest in the involvement after holding the courses about couple communication and pregnancy and childbirth support (21). These differences in the research results can be attributed to cultural misconceptions and the low education of husbands, which is consistent with the traditional beliefs of the current study’s participants.

The structural barriers, as the second category, were revealed in the present study. The implementation of the physiological childbirth promotion program has been partially successful in Iran. In order to achieve greater success, the physiological childbirth promotion program requires further investigation at the macro and micro levels of health system management (24). Both husbands and wives need to be educated about sexual and health issues. In the process of training in physiological childbirth, the necessity of the husband’s presence in childbirth education courses has been considered natural.

According to a study carried out in Iran, the major barriers to husbands’ involvement in their wives’ pregnancy care were their busy work schedules and economic problems (25). Probably, the Iranian husbands’ poor participation in the reproductive health of women needs adequate monitoring and evaluation of the childbirth education courses by the Ministry of Health of Iran to find solutions.

The findings of a study in Uganda revealed that the Ministry of Health policies were incompatible with the medical environments, and the lack of a safe space for husbands’ presence and participation in their wives’ delivery was a major barrier in the country (26), which is in agreement with the findings of the present study. It was reported that the implementation of the physiological childbirth program needs to be revised in terms of the environment and its performing conditions (3), which is consistent with the present study’s findings.

Men are mainly in charge of the family’s financial responsibilities, and there is not any protective law to encourage husbands’ involvement during their wives’ delivery, which is not congruent with the policy of increasing physiological childbirth and fertility rate in society and it is not included in the national physiological childbirth promotion program. According to study results, one of the most important barriers to husbands’ involvement in maternal health was their occupational responsibilities (27).

Men often feel that they do not have an important role in the birth of their child because they are not involved in the childbirth process. However, the necessity of husbands’ involvement in delivery preparation is discussed at the international level. In addition, the effects of husbands’ non-involvement, such as improper compatibility of couples during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period and their diminished supporting role, have been reported in a study (10). To successfully implement the program, there is a need to consider the implementation context since the physical space of the delivery room plays a key role in successfully implementing the physiological childbirth program.

Another category emerging in this study was individual barriers. It was indicated that mothers usually enter the delivery room alone and encounter pain and fear caused by this unknown process (28). These findings have been suggested in the two studies performed in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and Nepal (18, 20). Among the individuals around a pregnant woman, her husband has a significant impact on choosing the type of delivery. That is why the husband and his emotional and psychological support are very effective (13, 29).

The father plays the role of the supporter of the mother to have a better labor experience; however, the question is still raised whether this will be useful for all couples or not. A woman’s willingness to have her husband present during childbirth has been demonstrated in some studies. However, it was pointed out that husbands’ involvement might have a negative impact on women’s autonomy (15). The husband’s attendance in the delivery room increases anxiety in the parturient, affecting oxytocin release and labor difficulty. Finally, limited attention has been paid to the positive and negative consequences of the husband’s presence during childbirth (12). The findings of a study revealed that women were reluctant to have their husbands present at childbirth moment due to feeling shy (26). Nevertheless, in Germany, over 70% of husbands participating in childbirth were willing to support their wives even during hard childbirth (30).

The information requirements of fathers regarding spontaneous childbirth are not sufficiently met; the participants stated a lack of knowledge about involvement in the physiological childbirth promotion program as one of the main reasons for not participating in it. This barrier was also mentioned in the studies carried out in Ethiopia and Nepal (27, 31).

A limitation of this study is that its findings cannot be generalized to other populations or communities as it is a qualitative study.

5.1. Conclusions

Husbands’ involvement in maternal health is a relatively new issue in the healthcare system in Iran. The active participation of husbands in the effective implementation of the physiological childbirth plan is necessary. Removing the barriers against the active participation of husbands in childbirth preparation courses and supporting their wives in the delivery room is necessary. Some measures, such as the government paying childbearing allowances, incentive leaves for husbands to participate in the physiological childbirth process, increasing men’s awareness about reproductive health, and honoring the pregnant mother, can be helpful. It is necessary to use appropriate strategies to make men familiar with various aspects of maternity health to remove the barriers against the presence of husbands during childbirth and promote their involvement. It is recommended to implement programs to promote husbands’ involvement, such as employing trained male personnel in father-friendly clinics and scheduling the proper hours of providing services to help men have time off from work.