1. Context

Menorrhagia is defined as menstruation with regular intervals and excessive bleeding (more than 80 milliliters) or long duration (7 days or more) (1, 2). The evidence shows that one-third of women experience menorrhagia during their life (3). The World Health Organization estimates that 18 million women suffer from menorrhagia (4). Menorrhagia is the most prevalent cause of anemia in women (5), with a prevalence of 19.2% in Iran (6). This gynecological disorder considerably affects personal, familial, occupational, and social life (7) and physical and mental health (8), and therefore, its effective management is of great importance.

There are many different pharmacological, surgical, and non-pharmacological treatments for menorrhagia. Pharmacological treatments include hormonal and non-hormonal medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antifibrinolytic agents, progesterone, oral contraceptive medications, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (9). However, these treatments have different side effects, such as digestive problems, hepatic disorders, obesity, and thromboembolism. Moreover, the hypoestrogenic side effects of these treatments can lead to rapid bone destruction and menopausal symptoms, such as vaginal dryness and hot flushes, that in turn reduce the quality of life (10, 11).

Non-pharmacological treatments, such as complementary and alternative therapies, have received great attention in recent years due to the numerous side effects of pharmacological and surgical treatments. A review study into the Iranian Traditional Medicine (ITM) therapies for menorrhagia reported that the therapists of this medicine used different types of treatment for menorrhagia, including foodstuffs, dietary modifications, oral products, vaginal suppositories (Ferzajeh or Homoul), sitz bath (Abzan), lotions (Tela), purgatives (Estenja), and poultice (Marham) (9). The Iranian Traditional Medicine holds that foodstuffs, such as quince sauce (Cydonia oblonga), apple sauce (Malus domestica), rhubarb sauce (Rheum rhabarbarum), barberry sauce (Berberis vulgaris), pomegranate sauce (Punica granatum), bird meat with sumac (Rhus coriaria), almond (Prunus dulcis), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), and coriander (Coriandrum sativum), can reduce menorrhagia (12-15). Complementary and alternative methods have been used in different cultures for menorrhagia management (16), and many individuals believe that these methods are safer and have fewer side effects than pharmacological therapies (17).

A systematic review of three randomized clinical trials showed that ginger capsules and myrtle fruit syrup significantly reduced menstrual duration and menstrual bleeding severity, and Punica capsules were as effective as tranexamic acid in reducing menstrual bleeding severity (18). However, previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses included few clinical trials, focused on certain types of herbal products, and reported contradictory results. Therefore, further studies are necessary to produce firmer evidence in this area.

2. Objectives

The present systematic review and meta-analysis study was conducted to assess the effects of herbal products on menorrhagia.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Protocol

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (19). The protocol of this study was registered on the PROSPERO website (CRD42022316470).

3.2. PICO Components

The target population of this study consisted of women with menorrhagia from different ages and ethnic groups. The intervention group was the individuals who consumed herbal products, and the comparison group was the individuals who received the common and routine treatment of menorrhagia. The primary and secondary outcomes of the study were menstrual bleeding severity and number of menstrual days, respectively.

3.3. Search Strategy

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, Barekat Gostar, SID, Magiran, and IranDoc international and Iranian databases, in addition to the Google Scholar search engine, were searched without any time or language restrictions (updated until 02.07.2022). Search keywords were "menorrhagia", "heavy menstrual bleeding", "complementary therapies", "phytotherapy", and "herbal medicine". The "AND" and "OR" operators were used to refine search results. Moreover, the reference lists of the retrieved documents were manually searched to find any eligible study ( see in Supplementary File).

3.4. Main Syntax

The main syntax of the search protocol was as follows:

(Iran* OR Persian) AND (Traditional Medicine OR Home Remed OR Primitive Medicine OR Folk Medicine OR Indigenous Medicine OR Folk Remed* OR Ethnomedicine OR Complementary Therap* OR Complementary Medicine OR Alternative Medicine OR Alternative Therap* OR Medical Plant OR Medicinal Plant OR Pharmaceutical Plant OR Healing Plant OR Medical Herb* OR Medicinal Herb* OR Herb* OR Herbal Drug* OR Plant Extract*) AND (Menorrhagia OR “Abnormal Uterine Bleeding” OR “Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding” OR “Dysfunctional Uterine Blood Loss” OR “Dysfunctional Uterine Hemorrhage” OR “Excessive Uterine Bleeding” OR “Excessive Uterine Blood Loss” OR “Heavy Menstrual Bleeding” OR “Heavy Menstrual Periods” OR “Hypermenorrhea” OR “Menometrorrhagia” OR “Breakthrough Bleeding” OR “Intermenstrual Bleeding” OR “Intermenstrual Hemorrhage” OR “Vaginal Bleeding” OR “Vaginal Blood Loss” OR “Vaginal Blood Flow” OR “Prolonged Menstrual Bleeding” OR “Prolonged Menstrual Cycle” OR “Prolonged Menstrual Cycle Length” OR Spotting OR “Bleeding Between Periods”)

3.5. Inclusion Criteria

The present meta-analysis included studies that were randomized clinical trials. Eligible studies must have at least a primary outcome and have mentioned the effect of herbal products on the intensity of menstrual bleeding in women. Examining the secondary outcome (the effect of herbal products on the number of days of menstrual bleeding in women) is not mandatory in the reviewed studies. The reviewed studies should have the data required for data analysis (including the number of samples in the intervention group and the control group, the mean and standard deviation (SD) of bleeding intensity, and the number of days of menstrual bleeding in each of the following stages: pretest, the end of first, second, and third cycles)

3.6. Exclusion Criteria

Studies with non-random sample selection, case report studies, non-reporting of information required for data analysis (including the number of samples in the intervention group and the control group, the mean and SD of bleeding intensity, and the number of days of menstrual bleeding in each of the following stages: pretest, the end of first, second, and third cycles), low-quality studies based on the Cochrane Institute’s clinical trials quality assessment checklist, and unavailability of the full text of the studies were excluded.

3.7. Quality Appraisal

Two of the authors (M.F. and S.S.Y) independently appraised the retrieved studies using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials (20). This tool has seven items on the different types of bias in clinical trials with three possible responses, namely “Low risk of bias”, “Unclear risk of bias”, and “High risk of bias”. In case of any disagreement between the two authors, the third author re-appraised the intended document. If there is one type of bias in the text of the studies, it is a high risk of bias. On the contrary, if the desired bias does not exist in the text of the reviewed study, the risk of bias is low, and if none of these two conditions exist, the risk of bias is unclear (20).

3.8. Data Extraction

Two of the authors (M.F. and S.S.Y) independently extracted the necessary data in order to minimize biases in data collection and reporting. They used a checklist to document the extracted data that included items on the authors, publication year, design, sample size in each group, mean age in each group, country of study, the scientific names of the studied herbal products, and the pretest and the posttest means of menstrual bleeding severity. The third author re-assessed the accuracy of data extraction (comparison group: routine and common menorrhagia treatment group).

3.9. Data Analysis

Considering the quantitative nature of the primary outcome in these studies, the desired intervention effect size was calculated in addition to within- and between-group standardized mean differences (SMD). The SMD is a classic index of effect size that shows the power of the relationship between an intervention and an outcome. The SMD values closer to 0 indicate a weak relationship; however, SMD values equal to 1 and more indicate a strong relationship (21). An intervention-outcome relationship is considered insignificant when the confidence interval (CI) of SMD includes 0. The SMD is calculated using the following formula: SMD = New treatment improvement - Comparator (placebo) improvement/ Pooled standard deviation.

The pooled SD in equation adjusts the treatment-versus-placebo differences for both the scale and precision of measurement and the size of the population sample used (22). The included studies were combined based on their sample sizes, mean scores, and SDs. The SMD serves as a singular numerical approximation of the impact of a given treatment. The computation of 95% CI for the SMD can be of great assistance in comparing the efficacy of varying treatments. In circumstances where the SMDs of comparable studies lack overlapping CIs, it is reasonable to conjecture that the SMDs accurately represent factual distinctions between the studies. Conversely, SMDs with overlapping CIs might imply that the differences in SMD magnitude are possibly not statistically significant.

The Cochran’s Q test and the I2 index were used for a complete report of the necessary data for meta-analysis heterogeneity assessment. The I2 index was interpreted as less than 25%: Low heterogeneity, 25 - 75%: Moderate heterogeneity, and more than 75%: High heterogeneity (23). The random-effects model was used for meta-analysis due to high heterogeneity among the included studies. Data analysis was performed at a significance level of less than 0.05 using STATA software (version 14.0).

4. Results

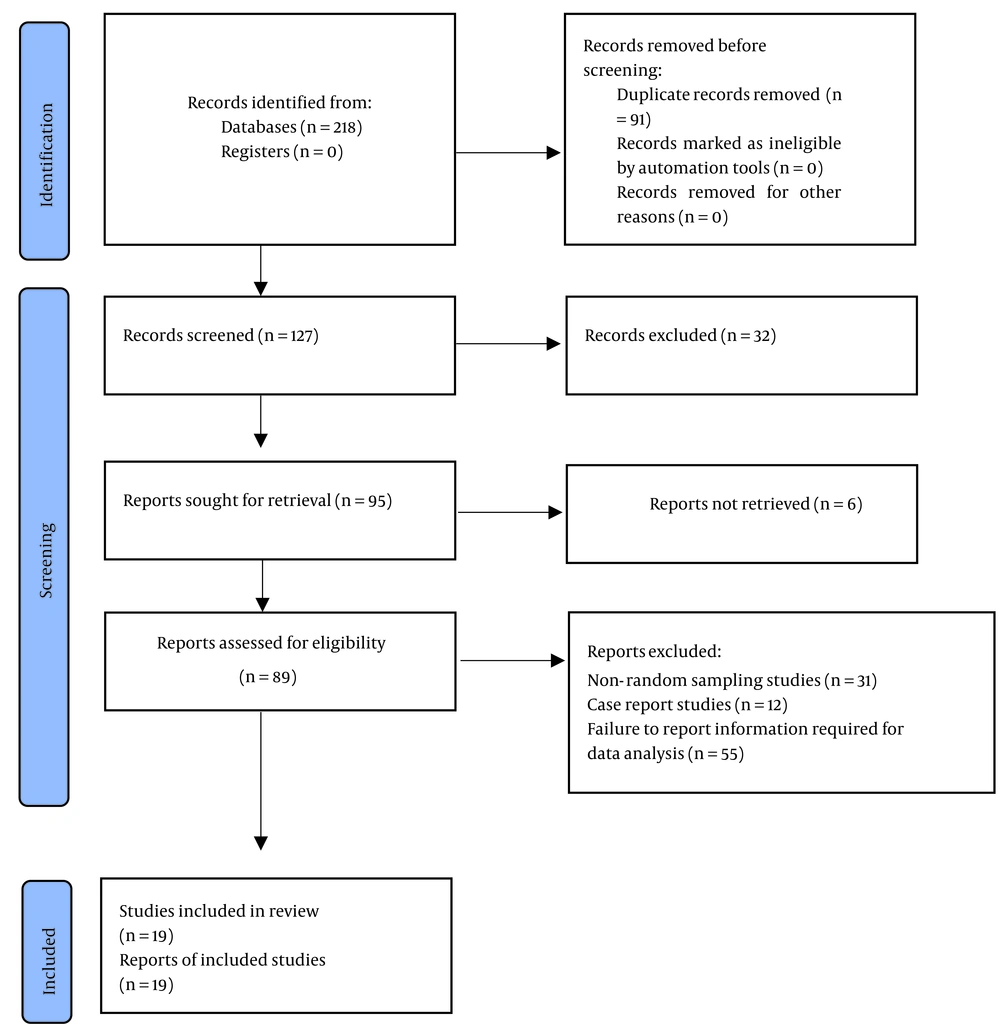

In the primary literature search, 218 studies were retrieved, 91 of which were removed due to their overlaps with each other, and the abstracts of the remaining 127 studies were reviewed. Then, 32 studies were removed due to full-text inaccessibility, and 76 studies were removed due to ineligibility. Finally, 19 eligible studies were included in the quality appraisal, which showed that all of them had acceptable quality and, therefore, were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

4.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

The 19 reviewed studies were published within 2013 to 2021 and conducted on 1715 women (856 and 859 subjects in control and intervention groups, respectively). The groups did not significantly differ from each other regarding participants’ age, menstrual bleeding severity, and number of menstrual days. The studies were into the effects of Persian Golnar (n = 3), quince (n = 2), ginger (n = 2), Achillea (n = 2), Vitex agnus-castus (n = 2), Urtica dioica (n = 1), frankincense (n = 1), purslane (n = 1), pomegranate peel (n = 1), Plantago (n = 1), plantain syrup (n = 1), lentil powder (n = 1), flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum) (n = 1), Capsella bursa-pastoris (n = 1), and Myrtus communis (n = 1). Two studies assessed the effects of four products (24, 25); nevertheless, the remaining studies each assessed the effects of one product. Seventeen studies were conducted in Iran (4, 24-39) and two studies in India (40, 41) (Table 1).

| First Author | Year of Publication | Country | Type of Study | Product Name | Number of Participants | Age (Mean) | Bleeding Severity at Baseline (Mean ± SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group | Control Group | Intervention Group | Control Group | Intervention Group | Control Group | |||||

| Ebrahimi-Varzane et al. (26) | 2020 | Iran | Randomized clinical trial | Achillea | 75 | 75 | 28.08 | 29.57 | 203.72 ± 13.12 | 184.59 ± 8.18 |

| Khademi et al.(27) | 2019 | Iran | Triple-blind clinical trial | Achillea | 45 | 45 | 27.56 | 27.22 | 7.39 ± 0.79 | 133.92 ± 20.612 |

| Shobeiri et al. (28) | 2014 | Iran | Double-blind clinical trial | Vitex agnus-castus | 25 | 25 | 22.68 | 21.6 | 30.2 ± 21.2 | 25.8 ± 17.8 |

| Mirghafourvand and Ahmadpour(24) | 2015 | Iran | Double-blind clinical trial | Vitex agnus-castus | 53 | 53 | 32.6 | 32.6 | 85.6 ± 45.2 | 73.1 ± 47.4 |

| Mirghafourvand and Ahmadpour(24) | 2015 | Iran | Double-blind clinical trial | Linum usitatissimum | 53 | 53 | 32.7 | 32.6 | 91.1 ± 61.9 | 73.1 ± 47.4 |

| Rahi et al. (29) | 2017 | Iran | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Quince | 72 | 74 | 32.5 | 32.3 | 173.6 ± 53.8 | 176.8 ± 54.3 |

| Mirzaei et al. (4) | 2018 | Iran | Randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled clinical trial | Purslane | 48 | 47 | 30.58 | 30.13 | 314.54 ± 105.3 | 319.74 ± 105.56 |

| Shafiee (30) | 2019 | Iran | Randomized clinical trial | Lentil powder | 22 | 22 | 38.9 | 35.1 | 383.5 ± 163 | 338.8 ± 141.3 |

| Sourteji et al. (31) | 2013 | Iran | Randomized triple-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | Urtica dioica | 45 | 45 | 25.24 | 26.71 | 315.16 ± 191.498 | 303.98 ± 213.839 |

| Goshtasebi et al. (32) | 2015 | Iran | Double-blind randomized controlled trial | Persian Golnar | 38 | 38 | 20-49 | 20-49 | 304.9 ± 176.11 | 304.4 ± 192.71 |

| Yousefi et al. (33) | 2020 | Iran | Double-blind, randomized clinical trial | Persian Golnar | 43 | 39 | 33.9 | 33.89 | 201.62 ± 144.11 | 185.58 ± 87.74 |

| Khodabakhsh et al. (34) | 2020 | Iran | Randomized triple-blind clinical trial | Plantain syrup | 28 | 28 | 40.78 | 40.21 | 323 ± 177.68 | 265.1 ± 150.02 |

| Kashefi et al. (35) | 2015 | Iran | Double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | Ginger | 38 | 33 | 15-18 | 15-18 | 113.73 ± 3.8 | 113.43 ± 5.5 |

| Eshaghian et al. (25) | 2019 | Iran | Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial | Ginger | 34 | 34 | 37.1 | 37.1 | 277.7 ± 9.3 | 311 ± 143.1 |

| Eshaghian et al. (25) | 2019 | Iran | Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial | Frankincense | 34 | 34 | 37.8 | 37.1 | 274.5 ± 139.9 | 311 ± 143.1 |

| Navaei et al. (36) | 2020 | Iran | Double-blind, randomized clinical trial | Plantago | 34 | 34 | 43.4 | 42.9 | 652.6 ± 189 | 775.3 ± 192 |

| Danesh et al. (37) | 2019 | Iran | Double-blind, randomized clinical trial | Capsella bursa-pastoris | 22 | 25 | 40 | 41.27 | 464 ± 283.61 | 445.92 ± 362.64 |

| Rahi et al. (38) | 2016 | Iran | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Quince | 72 | 74 | 32.5 | 32.3 | 38.7 ± 7.6 | 38.9 ± 8.6 |

| Imdad et al. (41) | 2017 | India | Randomized single-blind standard control | Persian Golnar | 30 | 30 | 18-40 | 18-40 | 295.3 ± 226.32 | 235.63 ± 96.82 |

| Umarami et al. (40) | 2020 | India | Single-blind randomized standard control | Myrtus communis | 20 | 20 | 26.5 | 26.95 | 231.05 ± 42.49 | 223.2 ± 50.08 |

| Salsali et al. (39) | 2019 | Iran | Triple-blind randomized controlled trial | Pomegranate peel | 28 | 28 | 20-50 | 20-50 | 352.071 ± 33.255 | 303.179 ± 24.84 |

Characteristics of the Reviewed Studies on Effects of Herbal Products on Menorrhagia

Within-group comparisons revealed a significant decrease in the intervention group in the bleeding severity in the first menstrual cycle (SMD = - 2.01, 95% CI: - 2.64 to - 1.38, P < 0.001), the second menstrual cycle (SMD = - 1.97, 95% CI: - 2.52 to - 1.43, P < 0.001), and the third menstrual cycle (SMD = - 2.70, 95% CI: - 3.58 to - 1.83, P< 0.001). Moreover, a significant decrease was observed in the intervention group in the number of menstrual days in the first menstrual cycle (SMD = - 0.86, 95% CI: - 1.22 to - 0.49, P < 0.001), the second menstrual cycle (SMD = - 1.09, 95% CI: - 1.71 to - 0.48, P < 0.001), and the third menstrual cycle (SMD = - 0.43, 95% CI: - 0.78 to - 0.07, P = 0.487) (Table 2).

In the control group, a significant decrease was observed in the bleeding severity in the first menstrual cycle (SMD = - 0.99, 95% CI: - 1.36 to - 0.61, P < 0.001), the second menstrual cycle (SMD = - 1.29, 95% CI: - 1.80 to - 0.78, P < 0.001), and the third menstrual cycle (SMD = - 1.41, 95% CI: - 2.03 to - 0.80, P < 0.001). Similarly, a significant decrease was observed in this group in the number of menstrual days in the first menstrual cycle (SMD = - 0.34, 95% CI: - 0.58 to - 0.11, P = 0.037) and the second menstrual cycle (SMD = - 0.80, 95% CI: - 1.44 to - 0.16, P < 0.001). Nevertheless, there was no significant change in the number of menstrual days in the third menstrual cycle (SMD = - 0.43, 95% CI: - 1.24 to 0.39, P = 0.024). The lowest bleeding severity and the fewest menstrual days in both groups were in the third and second cycles, respectively (Table 2).

| Variables and Time | Intervention | Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD (95% CI) | P-Value | I2 (%) | SMD (95% CI) | P-Value | I2 (%) | |

| Bleeding Severity | ||||||

| First cycle | - 2.01 (-2.64, -1.38) | < 0.001 | 96 | - 0.99 (-1.36, -0.61) | < 0.001 | 90.7 |

| Second cycle | - 1.97 (-2.52, -1.43) | < 0.001 | 94.5 | - 1.29 (-1.80, -0.78) | < 0.001 | 94.4 |

| Third cycle | - 2.70 (-3.58, -1.83) | < 0.001 | 96.5 | - 1.41 (-2.03, -0.80) | < 0.001 | 94.6 |

| Bleeding Days | ||||||

| First cycle | - 0.86 (-1.22, -0.49) | < 0.001 | 78.6 | - 0.34 (-0.58, -0.11) | 0.037 | 53.2 |

| Second cycle | - 1.09 (-1.71, -0.48) | < 0.001 | 88.9 | - 0.80 (-1.44, -0.16) | < 0.001 | 990.3 |

| Third cycle | - 0.43 (-0.78, -0.07) | 0.487 | 0 | - 0.43 (-1.24, 0.39) | 0.024 | 80.4 |

Within-group Comparisons Regarding Menstrual Bleeding Severity and Number of Bleeding Days in Intervention (Herbal Products) and Control Groups

Between-group comparisons showed no significant between-group differences regarding the bleeding severity at the pretest and in the third cycle and the number of menstrual days at the pretest and in the second and third cycles (P > 0.05). However, the bleeding severity in the intervention group was significantly less than in the control group in the first and second cycles, and the number of menstrual days in the intervention group was significantly less than in the control group in the first cycle (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Variables and Time | SMD | Minimum | Maximum | P-Value | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding severity | |||||

| Before | - 0.07 | - 0.44 | 0.31 | < 0.001 | 92.9 |

| First cycle | - 0.90 | - 1.43 | - 0.36 | < 0.001 | 95.3 |

| Second cycle | - 0.97 | - 1.52 | - 0.41 | < 0.001 | 95.6 |

| Third cycle | - 0.59 | - 1.18 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | 95 |

| Bleeding days | |||||

| Before | 0.14 | - 0.06 | 0.34 | 0.131 | 37.4 |

| First cycle | - 0.38 | - 0.66 | - 0.10 | 0.004 | 66.4 |

| Second cycle | - 0.20 | - 0.60 | 0.20 | < 0.001 | 77.7 |

| Third cycle | 0.15 | - 0.73 | 1.04 | 0.014 | 83.4 |

Between-group Comparisons Regarding Menstrual Bleeding Severity and Number of Bleeding Days in Intervention (Herbal Products) and Control Groups

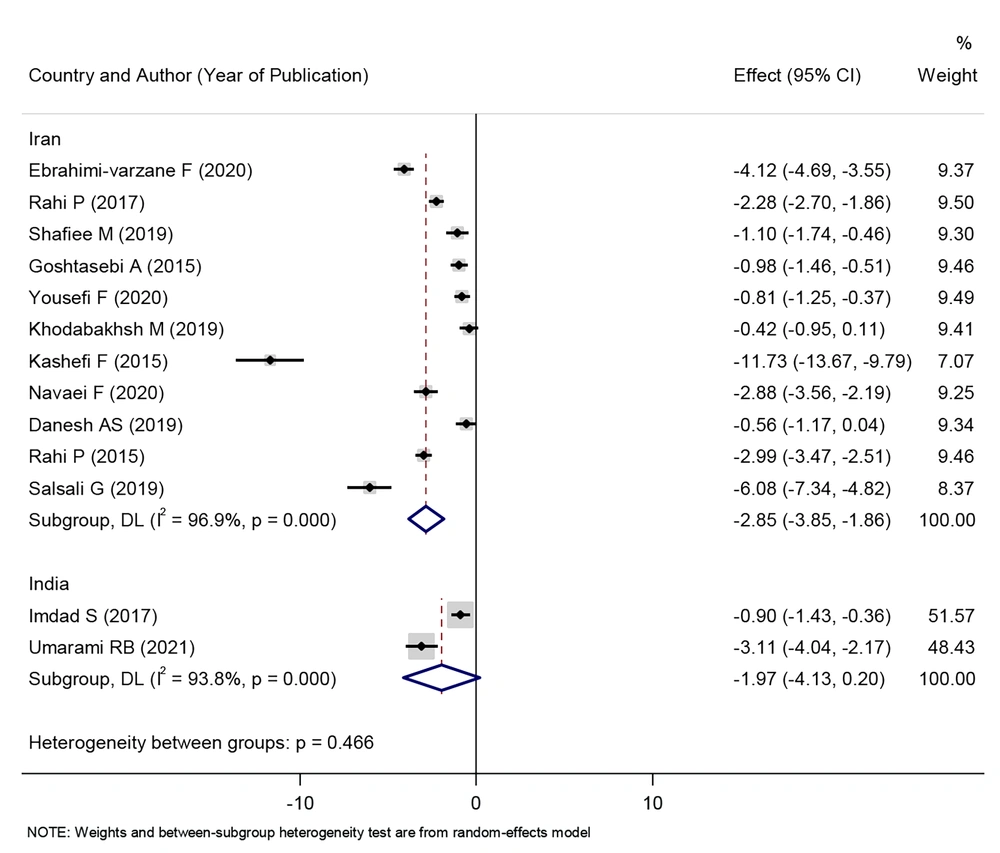

The effect of consuming herbal products on reducing the intensity of menstrual bleeding in Iran was statistically significant (SMD: - 2.85, 95% CI: - 3.85 to - 1.86, P < 0.001). However, the effect of consuming herbal products on reducing the intensity of menstrual bleeding in India was not statistically significant (SMD: - 1.97, 95% CI: - 4.13 to 0.20, P < 0.001) (Figure 2).

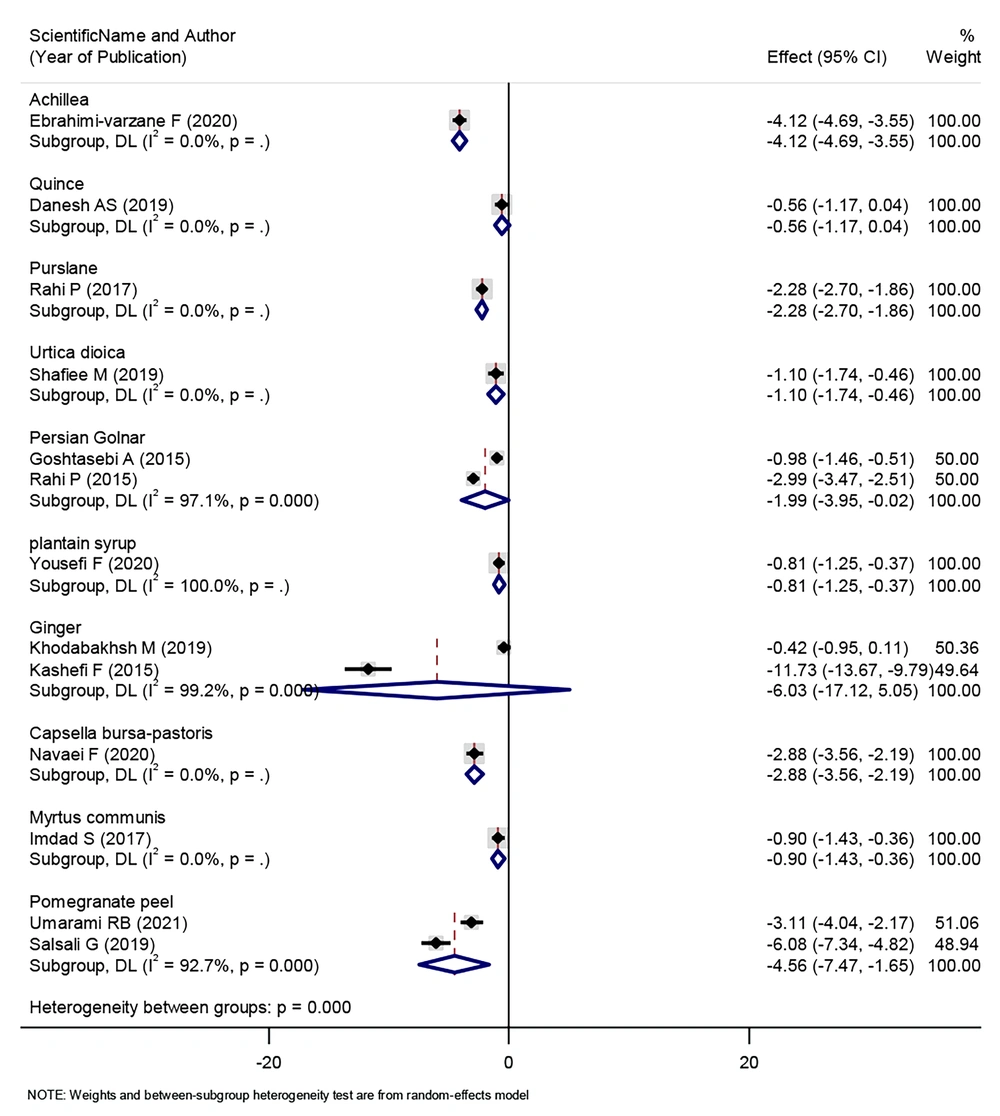

The effect of consuming some herbal products, such as Achillea, purslane, Urtica dioica, Persian Golnar, plantain syrup, Capsella bursa-pastoris, and pomegranate peel, on reducing the intensity of menstrual bleeding was statistically significant. On the other hand, there were herbal products, such as quince, ginger, and Myrtus communis, that did not change the intensity of patients’ menstrual bleeding (Figure 3).

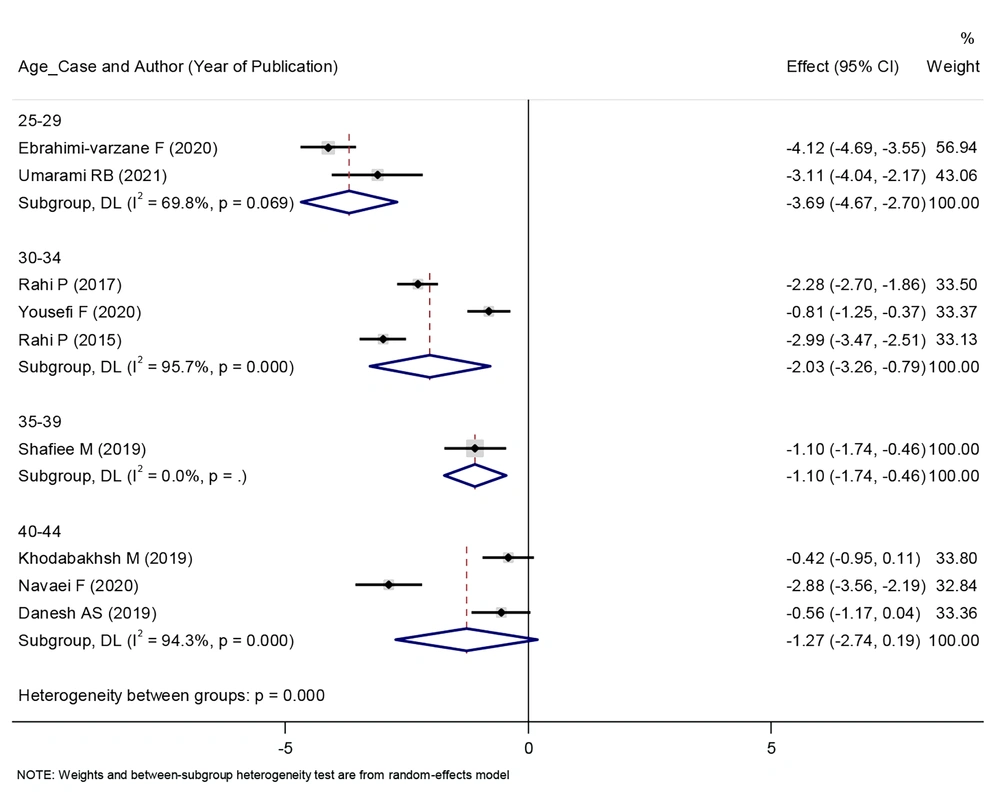

In patients who were between 25 and 39 years old, the consumption of herbal products reduced the intensity of their menstrual bleeding, and this relationship was statistically significant. Nevertheless, in individuals who were between 40 and 44 years old, the consumption of herbal products had no effect on the severity of their menstrual bleeding. This graph shows that as the patients age, the effect of herbal products on reducing the intensity of their menstrual bleeding decreases (Figure 4).

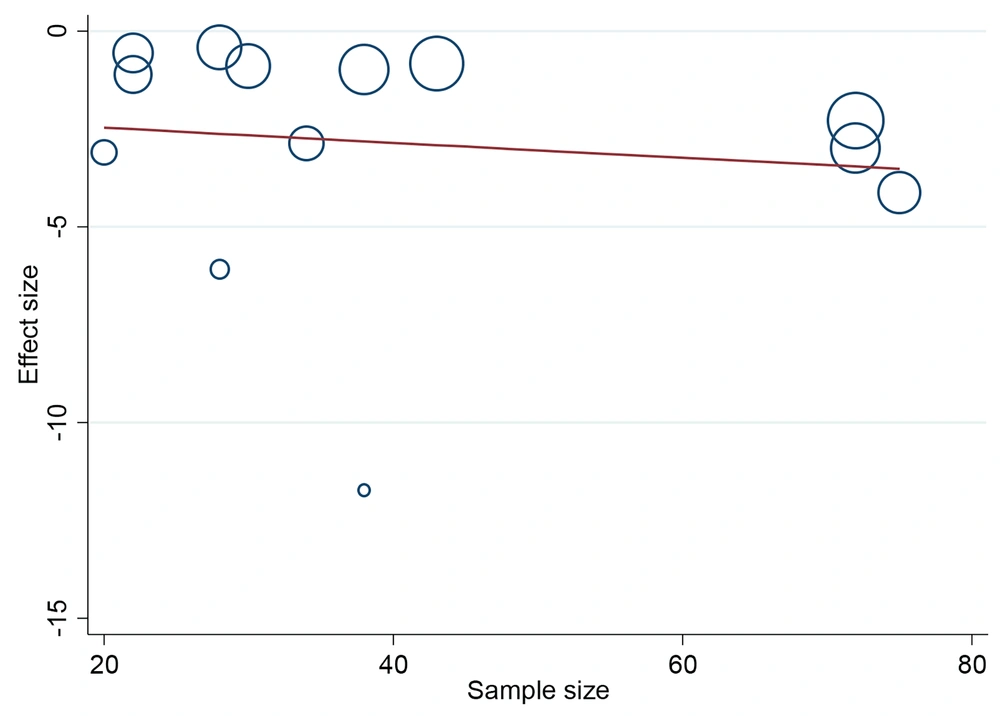

The meta-regression in Figure 5 showed that there is no statistically significant relationship between the effect size of “the effect of herbal products on the intensity of menstrual bleeding” and the number of the studied samples (P = 0.682). That is, it is not the case that in larger studies, which have a larger number of samples, the effect size of “the effect of herbal products on the intensity of menstrual bleeding” was greater and vice versa.

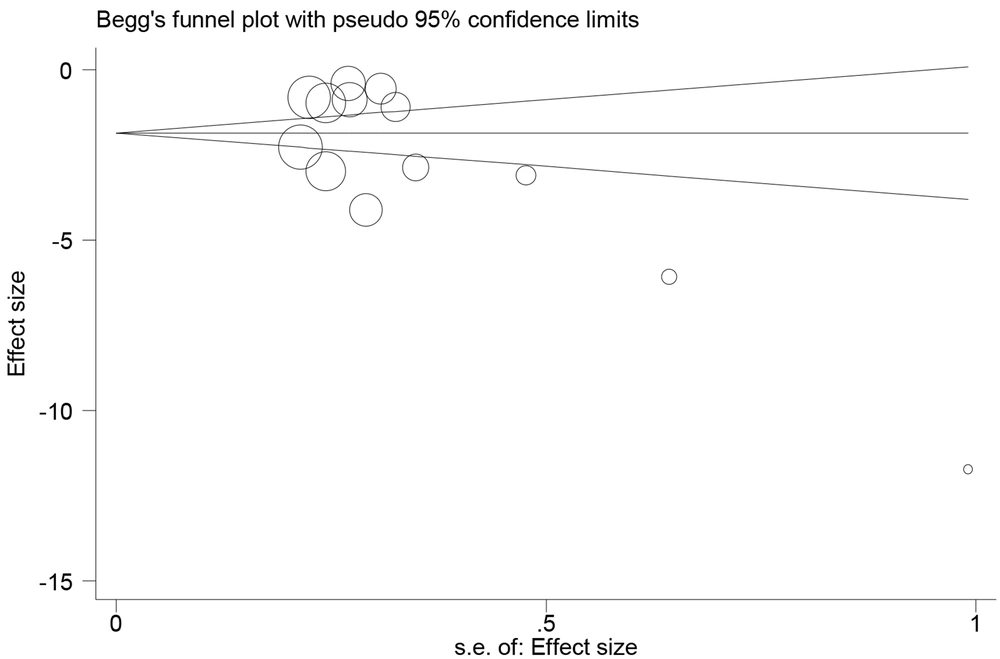

The distribution bias plot was significant (P = 0.025). This shows that the studies with negative results did not have a high chance of publication, and most of the studies published in this field pointed to the positive effect of herbal products in the treatment of menorrhagia and stated that the use of herbal products reduces the intensity. Menstrual bleeding and the number of menstrual days are also affected (Figure 6).

5. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis analyzed 19 clinical trials into the effects of different herbal products on menorrhagia among 1715 women. The findings showed that herbal products significantly reduced the menstrual bleeding severity and the number of bleeding days in the intervention group, denoting the effectiveness of these products in significantly alleviating menorrhagia. Between-group comparisons also indicated that the bleeding severity in the intervention group was significantly less than in the control group in the first and the second cycles; however, there was no significant between-group difference regarding the bleeding severity in the third cycle. This finding implies that the effects of herbal products on menstrual bleeding severity decrease over time. An explanation for this finding is that the effectiveness of herbal products might decrease with dose and time.

Moreover, insignificant between-group differences regarding bleeding severity can be attributed to the fact that women in the control group continued receiving routine treatments for menorrhagia. Between-group comparisons also revealed that the number of bleeding days in the intervention group was significantly less than in the control group in the first cycle; nevertheless, the between-group difference was not significant in the second and third cycles. This finding also confirms the greater effects of the lower doses and the shorter consumption periods of herbal products on menorrhagia.

A clinical trial on women with regular menstrual periods and menorrhagia compared the effects of mefenamic acid plus purslane in a 48-person intervention group to the effects of mefenamic acid plus corn starch capsule in a 47-person control group. The participants received the treatments every 8 hours during the first 3 days of two menstrual cycles. In agreement with the current study’s findings, the findings of the aforementioned study indicated lower bleeding severity and shorter bleeding duration in the purslane group (4). Another study demonstrated that quince was as effective as mefenamic acid in reducing menstrual bleeding severity in the first, second, and third cycles and introduced quince as a good substitute for mefenamic acid, particularly for patients with peptic ulcers (29). Quince has tannin and flavonoids and, therefore, can reduce menstrual bleeding through vascular contraction (42). Similarly, a study into the effects of mefenamic acid plus Achillea in an intervention group and mefenamic acid in a control group showed that Achillea significantly reduced menstrual bleeding severity but had no significant effects on menstrual bleeding duration. The aforementioned study also attributed the positive effects of Achillea on bleeding severity to its anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, and anti-prostaglandin effects (26). Additionally, a study indicated that a three-month intake of ginger significantly decreased menstrual bleeding, particularly in the first cycle (35). A major reason for the difference in the effects of herbal products in different studies is that the Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart used in these studies is a self-report scale, and data collection through it is subject to respondent bias.

In the year 2020, a clinical trial was performed on 120 women with menorrhagia in Tehran, Iran. The intervention group was subjected to treatment with 150 mg of yarrow in combination with 500 mg of mefenamic acid capsules, and the control group was treated with placebo capsules every 8 hours on 7 days of the menstrual cycle for 2 consecutive months. The researchers observed that menstrual bleeding duration and amount decreased in both groups. Nonetheless, the reduction in the duration and amount of menstrual bleeding was significantly greater in the yarrow group than in the placebo group (26).

A double-blind clinical trial was performed in Hamadan, Iran, focusing on female students experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding. The subjects were randomly assigned to one of four groups, receiving either phenylene drops, Vitagnos drops, mefenamic acid capsules, or placebo drops. The intensity of menstrual bleeding was assessed using Higam’s table during one cycle before and two cycles after the administration of the drug. Although there was no significant difference in the average intensity of menstrual bleeding among the four groups during one cycle prior to treatment, there was a notable distinction between the groups in two cycles after the initiation of treatment. In terms of reducing menstrual bleeding, mefenamic acid did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference compared to Fenlin and Vitagnos drops. Therefore, the two herbal medicines, Fenlin and Vitagnos, can be deemed effective and safe for reducing menstrual bleeding (28).

In 2015, a three-blind randomized clinical trial was conducted on 159 women in Tabriz, Iran. The study subjects were randomly allocated into three distinct groups consisting of 53 participants each. The first group received a daily dose of 25 g of flaxseed powder, and the second group received a single Vitagnos tablet daily; however, the third group received a placebo of both drugs. Subsequent to the intervention, significant reductions in menstrual bleeding scores were noted in the groups administered flaxseed powder and Vitagnos tablets within the initial 2 months. Although both Zaraktan and Vitagnos were observed to be effective in reducing menstrual bleeding, further research is required to fully establish their routine use (24).

In the above-mentioned three studies, the researchers showed that the use of herbal products could reduce the intensity and duration of women’s menstrual bleeding, and the use of herbal products, compared to the group that used mefenamic acid, either had the same effect or had a better performance. Therefore, by finding a safe dose and optimal duration of using herbal products, it is possible to use herbal products to reduce the symptoms of menorrhagia in patients who have contraindications to mefenamic acid.

A meta-analysis of six trials into the effects of fennel on menstrual bleeding showed that fennel significantly increased bleeding severity in the first cycle and had no significant effects on bleeding severity in the second cycle. The aforementioned study reported the low quality of the studies on the effects of fennel and highlighted the necessity of further studies in this regard (43). Some other studies into the effects of herbal products on menstrual bleeding reported the insignificant effects of these products, compared to conventional therapies, and attributed it to the regular use of conventional therapies for menorrhagia in the control group. Other influential factors in the contradictory results of studies regarding the effects of herbal products on menorrhagia include differences among studies in terms of participants’ characteristics, administration dose and duration of herbal products, and variations in herbal products. The current study came to the conclusion that if herbal products are considered separately from each other, the effect of consuming some herbal products, such as Achillea, purslane, Urtica dioica, Persian Golnar, plantain syrup, Capsella bursa-pastoris, and pomegranate peel, on reducing the intensity of menstrual bleeding was statistically significant. On the other hand, there were herbal products, such as quince, ginger, and Myrtus communis, that did not change the intensity of patients’ menstrual bleeding.

5.1. Study Limitations

Subgroup analyses based on administration dose and duration were impossible due to the paucity of eligible studies and the diversity of herbal products assessed in the studies. However, the wide variety of natural products used in the studies under review is one of the strengths of the current study.

5.2. Conclusions

This study concludes that herbal products are effective in significantly reducing menstrual bleeding severity and reducing the number of bleeding days, and their effects reduce over time. Further studies with larger samples are needed to produce more reliable results regarding the effects of herbal products on menorrhagia.