1. Background

Sexual relationship, affecting a woman's health and familial life, is one of the most complex aspects, including biological, social, economic, cultural, and spiritual dimensions. It is an integral part of life from birth to death and is an essential indicator of physical and mental health (1, 2). The WHO defines sexual health as physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being related to sexuality and sexual relationships. This does not simply mean the absence of disease, dysfunction, and sexual inability; it is the positive and respectable approach toward sexuality and making pleasurable and safe sex, which is not compulsive, discriminatory, and violent (3-6). Lottes has defined sexual health as the ability of women and men to have sexual pleasure and expression without the risk of venereal diseases, unintended pregnancy, coercion, violence, and discrimination. She believes that a person should have a positive attitude toward human sexuality, and there should be mutual respect and an informed, pleasurable, and safe sexual relationship (7). Sexual health increases a person's quality of life, personal relationships, and communication. Experiencing healthy and satisfying sexual relationships is a critical part of women's well-being and is associated with increased life satisfaction, objective health perception, and increased longevity (8, 9). The purpose of sexual health is to provide physical and emotional health, welfare for couples and families, and social and economic development of societies and countries. One's ability to achieve sexual health depends on access to comprehensive information and knowledge about sexuality, adverse consequences of risky sexual activities, access to quality sexual health care, and an environment that promotes sexual health (10).

There are many factors affecting sexual health, and the best and most helpful approach is using the biological, psychological, and social concepts, which are influenced by physical, mental, social, and cultural health and knowledge and previous relationships and experiences; social factors impact the women's sexual health differently (11). Considerable evidence, especially in the last two decades, demonstrates the effect of social factors on health, emphasizing that in addition to medical care, several social factors may affect a person's health (12-15). Social and economic policies shape the social determinants of health (SDH), the environmental conditions in which people are born, live, grow, educate, work, and age. They considerably influence individuals' health dimensions, performance, consequences, risks, and quality of life. SDH includes social gradient, stress, early life experiences, social exclusion, social support, work, unemployment, treatment, food, neighborhood, transport, poverty and access to facilities, and social welfare and health (14, 16, 17). The impact of SDH can accumulate over time and lead to health inequalities in the world, such as lower life expectancy, higher rates of child and maternal mortality, and higher disease burden, which are among the consequences of the social gradient. Thus, people with lower social status have a lower health and life expectancy than those with a higher social status (18).

The unequal distribution of resources leads to a social gradient. Therefore, policymakers should plan and implement targeted programs to diminish the social gradient (19). Based on our search in available databases, this is the first scoping review that has been conducted for this purpose. Previous studies have either been conducted on specific populations such as adolescents (20) or postmenopausal women (21) or have investigated the impact of some social determinants of health on a specific domain of sexual health (such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs)) (22). Considering the vital role of sexual health in women, spouses, family, and society, as well as the importance of SDH, this study aimed to review published studies on the social determinants of women's sexual health.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Search Strategy

In this scoping review, we used a systematic approach based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (23), and two authors independently searched the databases: PubMed, Medline, ProQuest, Cochrane Library, Web of Sciences, Scientific Information Database (SID), and Magiran. We found the original observational articles (cohort, cross-sectional, case-control) on social determinants of reproductive age women's sexual health that had investigated at least one SDH, including social gradient, social support, social exclusion, addiction, food, neighborhood, poverty, stress, life experiences, work, unemployment, and transport from January 2010 to January 2023. We excluded studies conducted on men, adolescents, and women outside of reproductive age. The search terms in the databases are given in Appendix 1 in the Supplementary File.

They searched each term related to SDH and one of the sexual health terms separately in other databases.

2.2. Data Extraction and Management

Two authors (i.e., FH & MA) independently extracted the relevant data and entered them in a predetermined form. In case of disagreement, they discussed it with a third author (i.e., SKH); however, they contacted the article's author if there were any ambiguities.

2.3. Assessment of Methodological Quality

Since the studies were observational, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (24) was used to evaluate the quality of the studies. Applying this scale, two authors (i.e., FH & MA) independently examined the articles in the dimensions of selection (maximum 5 points), comparability (maximum 2 points), and result (maximum 3 points). A third author (i.e., SKH) settled the disagreement in case of a dispute between the two authors. Articles with scores above six were considered good-quality papers.

3. Results

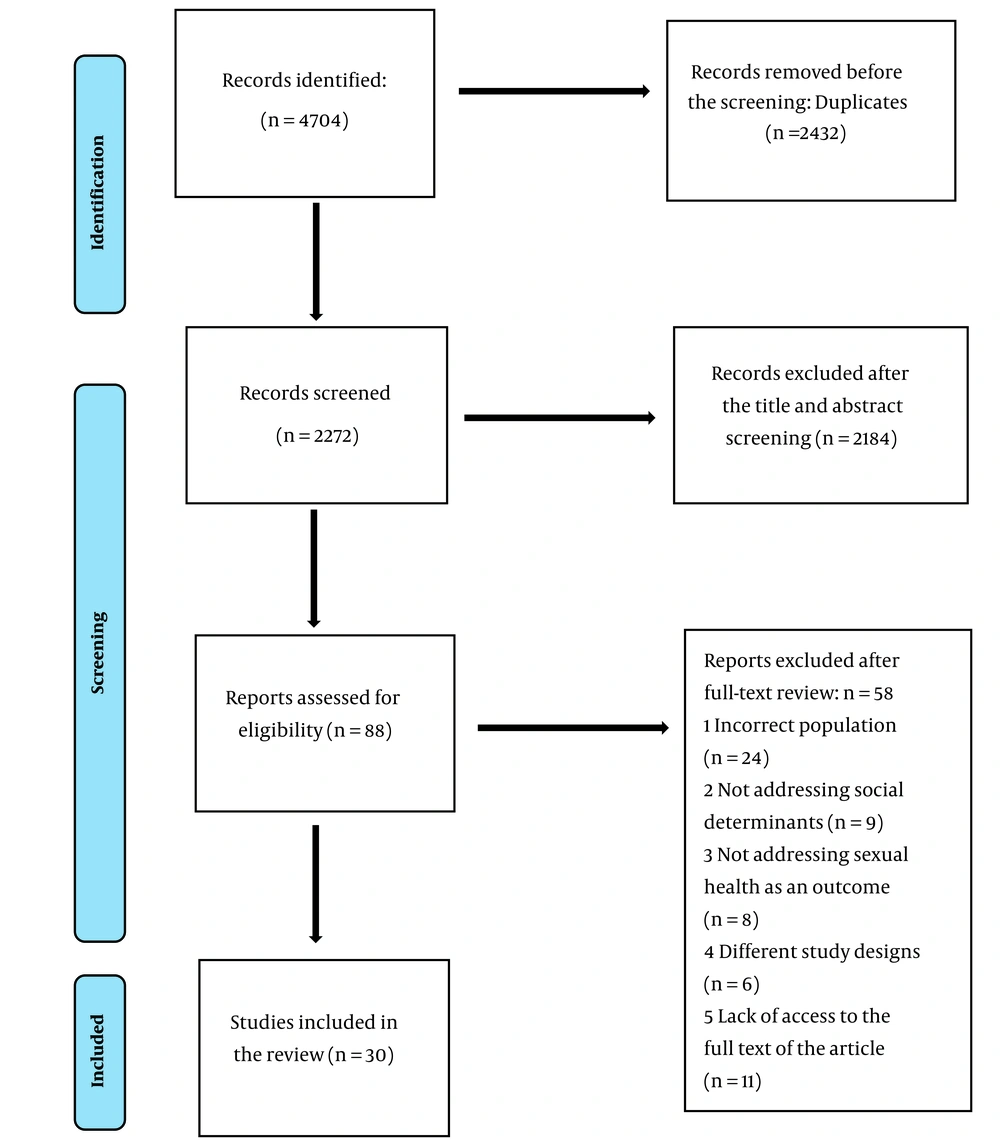

In this study, social determinants are given based on Michael Marmot's study, and studies were extracted based on the related factors (16). Two authors independently checked the databases and extracted 4704 articles in the initial review. After removing the duplicates, 2272 articles remained. A subsequent review of the title and abstract resulted in 88 articles. Then, the full texts of the articles were examined, and 58 articles were removed. Finally, 30 articles entered the scoping review (Figure 1).

3.1. Data Extraction and Management

The extracted data included the author, year, place, purpose, participants, instrument, main data, statistical analysis, exposure, the main outcome, and final study results (Table 1).

| No. | Author | Sample Size | Women's Sexual Health Variables | Social Determinants | Tools | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Babu et al. (25) | 1071 | (1) Having multiple sexual partners; (2) Paid sex in the last three months and frequency of sex with irregular sexual partners; (3) Condom use with regular partners during the last sexual act | Job stressor | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Workplace stress is associated with risky sexual behavior. |

| 2 | Chawhanda et al. (26) | 2070 | (1) Sexual and reproductive health service utilization; (2) Use of modern contraceptive methods | High migration communities | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Migration affects women's use of sexual and reproductive health services. |

| 3 | Harling et al. (27) | 119 | (1) Talk about sex; (2) Discuss STI prevention; (3) Received STI advised | Sources of social support | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Social support is associated with sexual behaviors. |

| 4 | Rojas et al. (28) | 267 | (1) HIV risk behaviors; (2) Multiple sex partners; (3)Sex under the influence of alcohol or other drugs; (4) Sex without a condom | (1) Mental health; (2) Sociocultural; (3) Marital status | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | There is a significant relationship between various sociocultural determinants, high-risk sexual behaviors, and HIV infection. |

| 5 | Marina Letica-Crepulja (29) | 300 | (1)Internet Addiction Test adapted for pornography use; (2) Reaction times to sexually explicit material cues; (3) Sexual arousal ratings of sexually explicit material | Stress induction and cortisol release | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Posttraumatic stress affects sexual function. |

| 6 | Ruiz de Vinaspre-Hernandez et al. (30) | 316 | Sexual satisfaction; | (1) Age; (2) Education; (3) Income; (4) Employment situation; (5) Sexual relationship; (6) Psychotropic drug use | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Social factors determining health, such as education, income, gender, and the use of psychoactive drugs, are sufficient for women's satisfaction with their sex lives. |

| 7 | Jorjoran Shushtari et al. (31) | 170 | Condom use | (1) Age; (2) Education level; (3) Marital status; (4) Place of living; (5) HIV knowledge; (6) Social level of the sexual partner; (7) Age and education of sexual partners; (8) Sexual network size; (9) Sexual network density; (10) Frequency of contact in the last month; (11) Drug or alcohol use before or at sex; (13) Perceived safe sex norm | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | The main determinants at the level of individual FSWs were their age and HIV knowledge.At the partner level, partner age and education, intimacy, tie duration, frequency of contact with a given partner, frequency of contact, perceived social support, and perceived safe sex norms were significantly associated with condom use. |

| 8 | Dehghankar et al. (32) | 420 | Sexual role | (1) Sexual health; literacy (Sexual Health Literacy Assessment Questionnaire); (2) Age; (3) Education level; (4) Occupation; (5) Age of the first child; (6) Age of spouse; (7) Education level of the spouse; (8) Duration of marital life; (9) Age at marriage; (10) Number of sexual intercourses per recent week; (11) Use of contraceptives | (1) Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire (2) Sexual healthliteracy (Sexual Health Literacy Assessment Questionnaire) | Employment status, level of education, duration of marital life, and the number of sexual intercourses per current week were the factors affecting women’s sexual function. |

| 9 | Banstola et al. (33) | 943 | Risky behavior (substance use, suicidal behavior, and sexual behavior) | (1) Age; (2) Sex; (3) Religion; (4) Ethnicity; (5) Education level; (6) Family type; (7) Parental education and occupation; (8) Economic status; (9) Family conflict and violence; (10) Perceived love and bonding with parents; (11) Family members’ use of substances; (12) Perceived parental control/monitoring; (13) Access to mass media; (14) Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES) was used to measure self esteem levels; (15) The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | (1) Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire; (2) Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES); (3) The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Self-esteem and social support are associated with risky sexual behavior. |

| 10 | Madbouly et al. (34) | 200 | The sexual role evaluation | (1) Age; (2) Education; (3) Occupation; (4) Family income (low or moderate versus high); (5) Living environment (urban or rural); (6) Body mass index; (7) The duration of the marriage; (8) Menstrual status (regular, irregular, postmenopausal); (9) Mode of delivery (normal labor, cesarean section); (10) Spouse’s sexual ability; (11) Chronic medical disease | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Age above 40, low socio-economic status, and dissatisfaction with a spouse's sexual ability are the most important predictors. |

| 11 | Wilson et al. (35) | 177 | AIDS-Risk Behavior | Lifetime Trauma and Victimization History (LTVH) | Lifetime Trauma and Victimization History (LTVH) | Violence and low income are associated with risky sexual behavior. |

| 12 | Mberu and White (36) | 2602 | Premarital sexual initiation | (1) Sexual initiation status; (2) Migration status; (3) Current age; (4) Religion; (5) Place of current residence; (6) Childhood place of residence; (7) Ethnic origin; (8) Education attained; (9) Years of exposure to risk; (10) Status/type of employment; (11) Household wealth index; (12) Index of media exposure | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Loss of social capital and exposure to the sexually permissive urban environment, age, gender, ethnic origin, education, independent living arrangement, and formal employment are associated with premarital sex initiation. |

| 13 | McCoy et al. (37) | 2000 | (1) Whether a woman entered into or stayed in a relationship longer than desired because of material goods; (2) Whether a woman could ask her partner to use a condom; (3) Sexual relationship power defined by the Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS) | Food Insecurity (Household Food Insecurity Access Scale [HFIAS]) | Food Insecurity (Household Food Insecurity Access Scale [HFIAS]) | The link between FI and HIV-related risk behavior may vary by household type. |

| 14 | Hall et al. (38) | 992 | Frequency of sexual intercourse | Stress Symptoms; Perceived Stress | Stress Symptoms; Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) | Stress symptoms are positively related to the frequency of sexual intercourse in these young women. |

| 15 | Overstreet et al. (39) | 186 | (1) Unprotected anal or vaginal sex with a partner who used IV drugs; (2) Unprotected anal or vaginal sex with a primary partner who was HIV-seropositive or whose status was unknown; (3) Unprotected anal or vaginal sex with a primary partner who had multiple (concurrent) sex partners; (4) Unprotected anal or vaginal sex with a non-primary partner whose HIV status was unknown; (5) Sex trade; | (1) Physical intimate partner violence (IPV); (2) Sexual Experiences; (3) Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom | (1) Conflict Tactics Scale-2 (CTS-2) (2) 10-item Sexual Experiences Survey (SES). (3) Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS) | Results illustrate that greater severity of psychological IPV is uniquely and directly related to more risky sexual behaviors. |

| 16 | Lutfi et al. (40) | 3643 | (1) Number of partners in the last 12 months; (2) Condom use at last sex | (1) Age; (2) Gender; (3) Marital status; (4) Educational attainment; (5) Income; (6) Racial residential segregation index values measure as less, more, or equal to 0.60; (7) Poverty is measured as the percentage of a Core Based Statistical Area (CBSA) with a family income below the poverty level | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Residential racial segregation is associated with risky sexual behaviors among non-Hispanic blacks aged 15 to 44. |

| 17 | Ramaswamy and Kelly (41) | 290 | (1) History of unintended pregnancy; (2) Lifetime history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (HIV/ AIDS, syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia); (3) History of trading sex | (1) Neighborhood violence; (2) Perception of neighborhood social capital and trust; (3) Neighborhood incarceration density | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Living in a neighborhood perceived to have low social capital is associated with a sexually transmitted infection history. |

| 18 | Raiford et al. (42) | 237 | (1) Two or more sex partners in the past three months; (2) Two or more sex partners in the past 30 days; (3) Primary sex partners three or more years older than themselves; (4) The main sex partner involved in a gang; (5) Unprotected vaginal sex with a primary partner in the past three months; (6) Unprotected vaginal sex with a principal partner in the past 30 days; (7) Substance use before or during sex in the past three months; (8) Substance use before or during sex in the past 30 days; (9) Exchange sex | (1) Age; (2) Education; (3) Employment status; (4) Barriers to employment; (5) Relationship status; (6) Lack of food at home; (7) Homelessness | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Young women reporting lack of food at home, homelessness, and low future and perceived education/employment prospects report sexual risk behaviors, considerable sex partners, risky sex partners, including older men and partners involved in gangs, substance use before sex, and exchange sex. |

| 19 | Ramaswamy et al. (43) | 28 | Sexual and reproductive health care use among women released from jail | Navigating social networks, resources, and neighborhoods | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Social support networks are the most common factor that supports women’s sexual and reproductive healthcare use. Possessing a medical home, reliable transportation, financial resources, and neighborhood dynamics are other factors mentioned by healthcare users. |

| 20 | Weiss et al. (44) | 447 | Risky sexual behavior (RSB) was assessed via ten items drawn from and modeled after the Sexual Risk Survey (SRS; Turchik & Garske, 2009). | (1) Traumatic exposure; (2) PTSD symptoms: PTSD; (3) Emotion dysregulation | (1) Life Events Checklist (LEC; Gray, Litz, Hsu, & Lombardo, 2004) (2) Checklist–Civilian Version (PCL; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) (3) Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) | The findings provide the mediating role of not accepting the negative emotions and difficulties controlling behaviors when distressed in the relationship between PTSD symptoms and later RSB. |

| 21 | Ruegsegger et al. (45) | 150 | Sexual behaviors (condom use, substance use before sex) | (1) Stigma HIV; (2) Social support | (1) Stigma Scale and the Stigma Mechanisms Scale) (2) (Four functional support scales for emotional/ informational, tangible, affectionate, and positive social interaction) | The study provides crucial evidence on stigma and social support for a highly marginalized population at high risk of STI/HIV. |

| 22 | McCauley (46) | 8984 | (1) Has sexual intercourse with a stranger; (2) Has ever had sexual intercourse with an IV drug user; (3) Has ten or more sexual partners. | (1) Household member incarceration; (2) Other stresses and family members' absence | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | The results provide little evidence that absence is a pathway linking household member incarceration to risky sexual health behaviors. |

| 23 | Martin et al. (47) | 275 | (1) A sexual health exam is defined as a pelvic exam; (2) Preventative care screenings for women included pap smears and mammograms; (3) In the past 12 months, did you receive any services to help reduce the violence in your home? (4) Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine receipt; (5) In the past three years, have you and your partner been to a doctor or other medical providers because you have been unable to become pregnant? (6) Did you receive any treatments for your pelvic pain in the past six months? (7) Current contraceptive use | (1) Addiction medicine clinic; (2) Primary care clinic | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Unmet RSH needs are less prevalent among participants in primary care than in the addiction medicine clinic, such as receiving a sexual exam in the past 12 months. The most common barrier to RSH service receipt is cost, followed by fear of judgment for drug/alcohol use and substance use disorder (SUD). |

| 24 | Park et al. (48) | 300 | Online Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder Scale (Song et al. as cited in Park and Shin) | (1) Perceived Stress; (2) Coping strategy (3) Brief Self Control. | (1) Scale developed by Cohen et al. as cited in Park and Shin) (2) Way of Coping Checklist (active coping strategy by Lazarus & Fokman) (3) Brief Self-Control Scale developed by Tangney et al. as cited in Park and Shin) | There are correlations between stress and active coping strategy, stress and lack of self-control, and lack of self-control and compulsive sexual behavior disorder. |

| 25 | Higgins et al. (49) | 2581 | (1) Female Sexual Function; Index (FSFI); (2) New Sexual Satisfaction Scale (NSSS) | Economic measures included; (1) How often did participants have enough money to meet their basic living needs in the past month; (2) Current receipt of at least one form of public financial assistance, including welfare and unemployment; (3) Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; (4) Federal poverty level; (5) Level of difficulty paying for housing, food, transportation, or medical care in the past 12 months. | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | They found strong and consistent relationships between sexual well-being and economic resources; those reporting more socio-economic constraints also reported fewer signs of sexual flourishing. |

| 26 | Puplampu et al. (50) | 568779 | (1) Having multiple sexual partners; (2) Not using condoms consistently | (1) Age; (2) Religion; (3) Marital status; (4) Education; (5) Employment status; (6) Wealth index; (7) Resides with spouse/partner; (8) First sex; (9) Circumcision; (10) Knows HIV status | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Determinants of H-RSB among the countries include age, sex, religious affiliation, marital status, educational level, employment status, economic status, age at first sex, and status of circumcision. |

| 27 | Bayoglu Tekin et al. (51) | 175 | Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) | (1) Age; (2) Pregnancy; (3) Number of children; (4) Duration of marriage; (5) Education; (6) Income level | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | Age, duration of the marriage, and the number of children adversely affect the FSFI scores. Intermediate education level and using a contraceptive method are related to higher FSFI scores. Pain scores are elevated in all participants independently from other parameters. |

| 28 | Leblanc et al. (52) | 279 | (1) Lifetime sexually transmitted infection [STI] diagnosis; (2) Concurrent partnerships; (3) Lifetime sex trading | (1) Childhood trauma (CHT); (2) Intimate partner violence (IPV); (3) Neighborhood stressors | (1) Self-reported rating of computerized history taking (CHT); (2) Self-reports of experiences of physical, emotional, verbal, or psychological abuse within a current intimate relationship; (3) Sociodemographic -medical questionnaire | In the full hierarchical model, IPV and life stress trauma are associated with lifetime sex trading, partner concurrency, and lifetime STI. |

| 29 | Diehl et al. (53) | 105 | Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX) | (1) Age; (2) Sexual orientation; (3) Educational level; (4) Ethnicity; (5) Marital status; (6) Monthly income; (7) Employment status; (8) Religious affiliation; (9) Short Alcohol Dependence Data (10) Drug Abuse | (1) Sociodemographic -medical questionnaire (2) Short Alcohol Dependence Data (SADD) Questionnaire (3) Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST20) | Female sexual dysfunction symptoms are common among the participants and are primarily associated with high levels of nicotine use. |

| 30 | Efrati et al. (54) | 132 | Compulsive sexual behavior disorder and risky sexual action tendencies | (1) Early life trauma; (2) Negative life events; (3) Positive life events; (4) Substance use disorder | Sociodemographic-medical questionnaire | The findings indicate that young women with substance use disorder have higher compulsive sexual behavior disorder symptoms and have more prevalent risky sexual action tendencies than the control group. |

Data Extraction and Management About Social Determinants of Women's Sexual Health

This scoping review study was intended to determine the social determinants of women's sexual health. The findings supported the effective role of SDH on sexual health, such as socioeconomic status (40, 42, 49), personal determinants (30, 31, 34, 50, 51), neighborhood (40, 41, 43), social support (27, 33, 43), violence (39, 55-57), addiction (54), migration (26, 58-60), stress (29, 44, 46, 61, 62), and education (32).

3.2. Assessment of Methodological Quality

As tabulated in Table 2, assessing the methodological quality of eligible studies using the tool (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale) demonstrated that most articles received a score above 6.

| No. | Article Specification | Ref. | Selection (0-4) | Comparability (0-3) | Outcome (0-3) | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Babu et al., 2013, USA | (25) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 2 | Chawhanda et al., 2022, Africa | (26) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 3 | Harling et al., 2018, Africa | (27) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 4 | Rojas et al., 2016, USA | (28) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 5 | Marina Letica-Crepulja, 2019, Croatia | (29) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 6 | Ruiz de Vinaspre-Hernandez et al., 2022, Spain | (30) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| 7 | Jorjoran Shushtari et al., 2021, Iran | (31) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 8 | Dehghankar et al., 2022, Iran | (32) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| 9 | Banstola et al., 2020, Japan | (33) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| 10 | Madbouly et al., 2021, Saudi Arabia | (34) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 11 | Wilson et al., 2012, Chicago | (35) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| 12 | Mberu and White, 2011, Nigeria | (36) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 13 | McCoy et al., 2014, Tanzania | (37) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 14 | Hall et al., 2014, Michigan | (38) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 15 | Overstreet et al., 2015, Carolina | (39) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 16 | Lutfi et al., 2015, USA | (40) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 17 | Ramaswamy and Kelly, 2016, USA | (41) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 18 | Raiford et al., 2014, USA | (42) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 19 | Ramaswamy et al., 2018, USA | (43) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| 20 | Weiss et al., 2019, Spain | (44) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 21 | Ruegsegger et al., 2021, USA | (45) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| 22 | McCauley, 2021, USA | (46) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 23 | Martin et al., 2022, USA | (47) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 24 | Park et al., 2021, Korea | (48) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 25 | Higgins et al., 2022, USA | (49) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 26 | Puplampu et al., 2021, Ghana | (50) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 27 | Bayoglu Tekin et al., 2014, Turkey | (51) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 28 | Leblanc et al., 2020, USA | (52) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 29 | Diehl et al., 2013, Brazil | (53) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| 30 | Efrati et al., 2022, Israel | (54) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

Assessment of Methodological Quality of the Eligible Studies (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale)

4. Discussion

The findings of the present study demonstrated that socioeconomic status, personal determinants, neighborhood, social support, violence, addiction, immigration, stress, and education affect women's sexual health as social determinants of health.

4.1. The Effect of Socioeconomic Factors on Sexual Health

In the present study, three articles devaluated the effect of this factor on sexual health (40, 42, 49). Higgins et al. observed that people with more socio-economic constraints reported fewer symptoms of sexual flourishing. They emphasized that public health should focus on economic reforms, reducing poverty, and eliminating economic gradient as critical aspects of helping people achieve their sexual health and well-being (49). In addition, a study conducted by Raiford et al. observed that young women who reported a lack of food at home, homelessness, low prospects, and poor educational and job outlook were more likely to have high-risk sexual partners, including elderly spouses and smuggler partners. They reported drug use before sex and sex in exchange for money. This study has emphasized that the economic conditions among these young women may lead to sexual risks due to desperation, the need for survival, or other factors (42). A study was conducted in 2013, the results of which were consistent with the current study and indicated that people of disadvantaged socioeconomic positions had less satisfying, more unsafe, and more abusive sexual relationships. Women experienced more sexual abuse and had less satisfaction at their first intercourse (63). Therefore, the results of the previous studies generally show that social and economic restrictions have a great impact on sexual health, especially risky sexual behaviors.

4.2. Personal Determinants

In this study, four articles investigated the effect of personal determinants on sexual health (30, 31, 34, 50, 51). One study revealed that age, duration of the marriage, and the number of children have a negative effect on women's sexual function, while education level and the use of contraception positively influence it (51). Examining the factors affecting high-risk sexual behaviors, Puplampu et al. demonstrated that age, gender, religious affiliation, marital status, education level, employment status, economic status, age at the first sex, and circumcision are related to risky sexual behavior (50). However, Madbouly et al. determine the predictors of sexual dysfunction in women as age over 40, unemployment, low-to-moderate socioeconomic status, dissatisfaction with the spouse's sexual ability, and high weight and height; they believed that the most important predictive factors affecting sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm were age over 40, low socio-economic level, and dissatisfaction with the sexual ability of spouse (34). Furthermore, Jorjoran Shushtari et al. confirmed that the sexual partner's age and education, sexual intimacy, relationship duration, frequency of contact with a given partner, perceived social support, and perceived safe sex norms are significantly related to the appropriate use of condoms (31). Finally, Ruiz de Vinaspre-Hernandez et al. reported that SDH, such as education, gender, and psychoactive drug use, greatly influence women's satisfaction with sex life (30).

4.3. The Effect of the Neighborhood on Sexual Health

Three studies evaluated this factor (40, 41, 43). The social environment and the place where people live are related to high-risk sexual behaviors. Neighborhoods with less social and institutional support and higher crime have poorer health outcomes (64). High-risk sexual behaviors decrease when neighborhood organizational supports reduce the crime-caused stress (65-67). In a 2018 study, Ramaswamy et al. reported that having health centers in the neighborhood, reliable transportation, financial resources, and neighborhood dynamics are among the factors influencing women's use of sexual and reproductive health care. They emphasized that public health policymakers should pay special attention to the social background of marginalized women, understand the risks to their sexual health, and plan to provide sexual and reproductive health care services for them (43). In a 2015 study, Ramaswamy et al. showed that the density of incarcerated participants in neighborhoods with low socioeconomic status was three times higher than in other neighborhoods. In addition, the history of the sex trade for money, drugs, or life necessities is much higher than in other areas. Living in a neighborhood with low social capital is associated with a history of sexually transmitted infections. They concluded that understanding these social effects on women's sexual health, especially at the neighborhood level, can provide essential insights into planning and implementing the necessary interventions (41). Finally, Lutfi et al. reported that risky sexual behavior was strongly associated with residential segregation, neighborhoods with a high concentration of non-Hispanic blacks, and the accumulation of non-Hispanic blacks in the area (40). A study was conducted in 2022, and the results demonstrated that strengthening supportive and safe neighborhood environments can reduce risky sexual behaviors and unwanted pregnancies (68). A review study was conducted in 2022, and the results demonstrated that neighborhood disadvantage is one of the most robust correlates of HIV risk. This study emphasized that HIV is not randomly distributed in neighborhoods but instead concentrated in neighborhoods characterized by factors such as high rates of poverty, crime, and abandoned buildings. Most of the conducted studies are related to the influence of the neighborhood on the sexual health of young people. Most of the conducted studies consider the neighborhood factor to be effective on risky sexual behaviors, unwanted pregnancies, and the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (69-71), which is in line with the results of our study. This study indicates that HIV is not randomly distributed in neighborhoods but instead is concentrated in neighborhoods characterized by factors such as high rates of poverty, crime, and abandoned buildings. Most of the conducted studies were related to the influence of the neighborhood on the sexual health of young people. Most of the conducted studies considered the neighborhood factor to be effective on risky sexual behaviors, unwanted pregnancies, and the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (69-71), which is in line with the results of our study.

4.4. Social Support

Three studies evaluated the effect of social support on sexual health (27, 33, 43). Harling et al. studied sources of social support. They presented some sexual behavior advice in 2018, demonstrating that people at higher risk of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV receive social support from different groups and are strongly influenced by gender and age. Therefore, health workers can provide various opportunities to exploit the social networks of peers, friends, and family to provide effective HIV prevention interventions and influence this group's attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (27). Moreover, studies have shown that people who receive tangible and emotional support and have strong attachments to their families cope better with stress and report less alcohol and illegal substance consumption. Likewise, they are less likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors (72-74). Furthermore, Mino et al. controlled the age, gender, and homelessness among women. They showed that emotional support reduced the frequency of drug injection and the risk of injection-related HIV infection (75). Another study demonstrated that people receiving social support from trusted partners were less likely to use condoms (28). In another study, Ruegsegger et al. revealed that improper use of condoms and drug use before sex was related to the perception of stigma and the level of perceived social support (45). Ramaswamy et al. found that social support network was the most common factor that contributed to the use of sexual and reproductive health care for women (43). Finally, Banstola et al. concluded that social support was associated with sexual behavior (33).

4.5. The Effect of Education on Sexual Health

One study evaluated this factor (32). Dehghankar et al. concluded that sexual health literacy influences women's sexual function. In other words, the chance of having a good sexual function in women with sufficient health literacy is 4.222 times higher than in those with inadequate health literacy. Moreover, employment status, education level, duration of the marriage, and number of sexual intercourses in the last week affect the women's function (32). The relationship between sexual health and education has been confirmed in studies; therefore, educational policies should greatly contribute to reducing stigma by providing accurate sexual health information and counseling. Such training should be provided in the workplace, schools, health centers, and the community.

A systematic review was conducted in 2020 to identify influential factors in the sexual health of Muslim women. The authors reviewed 54 articles studying these women's poor knowledge and negative attitudes toward sexual health services. They found that the barriers to contraceptive use among Muslim women included a lack of basic fertility knowledge, insufficient knowledge about contraception, misconceptions, and negative attitudes. In other words, religious and cultural beliefs were barriers to using contraceptive methods and access to services and information on sexual and reproductive health. Correspondingly, the opposition of the husband, family, and society significantly impacted this issue. The fear of being stigmatized for having premarital sexual relationships among unmarried women was the main obstacle to seeking and accessing sexual and reproductive health services. They emphasized the need for planning interventions for removing barriers, improving knowledge, changing attitudes to make informed choices, using sexual health services, and facilitating sexual and reproductive well-being for Muslim women (76-79). Therefore, the results of the mentioned studies are consistent with our study.

4.6. The Effect of Stress on Sexual Health

Five studies evaluated this factor (29, 44, 46, 61, 62). Chronic stress significantly increases risky and compulsive sexual behavior in women (44, 46). Moreover, increased stress increases alcohol and drug consumption (28). Researchers attribute stress to women's daily life and social environment, including poor socioeconomic conditions, segregation experience, lack of access to social and medical services, migration experience, lack of access to disease prevention education, limited educational opportunities due to cultural and language barriers, and no health insurance (61, 62). Moreover, studies show that acute stress strengthens sexual stimuli by increasing cortisol and affects high-risk sexual behaviors (29). Research has shown that the frequency of sexually active relationships among women with stress (43%) is higher compared to women without stress symptoms (35%), with a P-value < 0.001. After controlling other variables, women with stress symptoms are 1.6 times more likely to have more sexual intercourse per week than women without stress (OR 1.6, CI 1.1 - 2.5, P = 0.04) (30). Another study reveals that intimate partner violence and life-stress trauma are associated with the coexistence of extramarital sex and sexually transmitted diseases for a lifetime (52). Therefore, all reviewed studies have emphasized the impact of stress on sexual health

4.7. The Effect of Addiction on Sexual Health

Two studies evaluated this factor (54). Women who use drugs are more likely to engage in high-risk and compulsive sexual behaviors than those who do not (54). Martin et al. demonstrated that unmet sexual health needs, such as receiving a sexual examination in the past 12 months, are lower in addiction clinics (55.6% vs. 30.1%). The most common barrier to receiving sexual health services is cost, followed by fear of judgment (47). The results of a review study indicated that there is a relationship between substance use disorders and the prevalence of HIV and acute viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and high-risk sexual behaviors (80). Also, a study was conducted in 2018 with the aim of determining the relationship between substance use and sexual behaviors in patients with substance use disorder. In this study, a strong relationship between risky sexual behaviors and drug use was observed (81). Therefore, the results of these studies are consistent with our study, and it appears that addicted women are more frequently engaged in risky sexual behavior and do not seek health services due to the fear of being judged.

4.8. The Effect of Violence on Sexual Health

Four studies evaluated this factor (39, 55-57). Intimate partner violence is associated with substance abuse and other risky behaviors among the poor living in an urban environment, increasing the risk of engaging in risky sexual behaviors (55, 56, 82). Due to the increase in risky sexual behaviors, violence surges the risk of HIV infection (28, 57). Overstreet et al. demonstrated that intense violence of an intimate partner is uniquely and directly associated with more risky sexual behaviors (39). Similarly, Wilson et al. believe that exposure to violence is related to unsafe sex, more partners, and inappropriate condom use. They state that violence includes physical, neighborhood, and sexual partner violence (35). In general, domestic violence is one of the barriers to receiving reproductive sexual health care (1). A review article was conducted in 2021 with the aim of investigating the impact of violence on women's sexual health and fertility. The results of this study demonstrated a consistent relationship between violence and the number of sexual partners, women's conditions (such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs)), unwanted pregnancy, and abortion (83), which is consistent with the result of the current study and shows that intimate partner violence is associated with substance abuse and other risky behaviors among the poor living in an urban environment, increasing the risk of engaging in risky sexual behaviors, and due to the increase in risky sexual behaviors, violence surges the risk of HIV infection.

4.9. The Effect of Migration on Sexual Health

Four studies evaluated this factor (26, 58-60). It is estimated that international migration was 214 million in 2010, reached approximately 244 million in 2015, and increased to 258 million in 2017 (26, 58, 59). In other words, about one billion people live outside their birthplace or original residence (84). Most migrants are at the reproductive age (15 - 49 years old) with a mean age of 39 (58). The migration of people of reproductive age plays a crucial role in public health and access to sexual and reproductive health services (60, 85-87). The articles we reviewed confirm an inequity in the use of sexual and reproductive health services between migrants and non-migrants. Migrant women experience less use of contraceptive methods, intimate partner violence, a high rate of abortion and abortion complications, high HIV prevalence, maternal complications, and high mortality compared to non-migrant women (88-90). Mberu and White revealed that migration was directly related to the early initiation of sex, loss of social capital, and exposure to new urban environments that increased young people's desire for sex. They believed that age, gender, ethnic origin, education, independent living, and formal employment play a role in sexual initiation (36). A review study was conducted in 2019 with the aim of investigating the impact of immigration on sexual health. The results of this study showed that HIV acquisition and high-risk sexual behavior are more common among male and female immigrants compared to their non-immigrant counterparts, and the results of the meta-analysis showed that immigration is significantly associated with an increased risk of HIV infection (aOR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.33 - 2.14; I2 = 35.0%), and there is an urgent need for effective combined HIV prevention strategies (including biomedical, behavioral and structure) that targets the immigrant population (91). Another systematic review was conducted, which reviewed 12 studies to identify the social determinants of sexual and reproductive health and the rights of migrants. The findings indicated that the economic crisis and hostile discourse on migration, limited rights, rights and administrative barriers, insufficient resources and financial restrictions, poor living and working conditions, cultural and language barriers, stigma and discrimination based on migration status, gender, and ethnicity affected sexually transmitted infections, sexual violence, and unintended pregnancy (92). The result of this study is consistent with our study.

Finally, a systematic review investigated 14 studies to determine the impact of SDH on adolescents' sexual health in Australia. The results indicated that the SDH, such as access to health care, poverty, drug use, educational disadvantage, sociocultural context, gender inequalities, identity, and social disadvantages, affected adolescents' sexual behaviors and sexual health risks (93). A cross-sectional study on 1000 Iranian married women of reproductive age determined various social and demographic factors on low sexual desire. They showed that age at the first sex, the duration of the marriage, and the level of satisfaction with income were associated with low sexual desire (94). Therefore, social factors can affect different aspects of sexual health. In general, the literature supports the findings of the present review.

4.10. Limitations

This review examined articles from 2010 through 2023 in a proscribed set of databases. While a substantive number of studies were included in the review, we missed related papers published outside this period, and due to the heterogeneity of the studies, we couldn't conduct a meta-analysis. Another limitation of this study is that the study was conducted on women of reproductive age group, and studies on adolescent girls and sexual minorities were excluded from the study.

4.11. Conclusions

SDH, such as socioeconomic status, individual determinants, neighborhood, stress, addiction, education, immigration, and social support, affect sexual health. Therefore, health policymakers and service providers must evaluate various dimensions of SDH according to the conditions and needs of each person to improve and promote women's sexual health. Finally, they should plan and implement necessary strategies to eliminate identified obstacles. To conduct a meta-analysis, researchers can evaluate different dimensions of SDH on various aspects of sexual health in various societies. Moreover, SDH on men's sexual health and fertility requires investigation. Few cross-sectional studies have been conducted on the role of SDH in sexual health; there is a need for more studies. In addition, SDH does not have an organized tool for use in observational studies. Therefore, after reviewing and identifying the influencing factors, researchers can accomplish the necessary investigations to develop an instrument for measuring SDH. Health policymakers must plan and implement the necessary interventions to eliminate the effect of social, economic, cultural, and individual inclinations on receiving sexual health services and the required education. Moreover, healthcare professionals should screen people of all ages and conditions for sexual health and address the factors affecting it, including social support and other factors. In addition, they should refer them for counseling and treatment regarding each person's problem. Finally, they should continuously provide the essential education to improve sexual health literacy individually and based on one's level of literacy and learning.