1. Background

Domestic violence (DV), also known as intimate partner violence (IPV), is a pervasive and destructive public health issue (1). It includes a range of negative behaviors directed at a romantic partner and remains a hidden societal problem (2). Emotion regulation (ER) is a complex, multifaceted, and learnable process that involves managing emotional experiences for personal purposes. It is acquired through parental coaching, modeling, direct interventions, conversations, the quality of the parent-child relationship, and the unique influences of peers and siblings as social influencers (3). Individuals experiencing DV face debilitating physical, mental health, and financial outcomes (1). Therefore, research that informs related factors and prevention strategies is crucial (4), and violence intervention programs are essential to interrupt the cycle of violence (5).

The prevalence of DV varies globally. Research indicates that one in three women and one in four men experience DV at some point in their lives (6). In the Middle East, reported prevalence rates are higher in countries such as Yemen (26%), Morocco (25%), Egypt (23%), Sudan (22%), and Algeria (21%), while lower rates are observed in Jordan, Lebanon, Tunisia (6%), and Libya (7%). Palestine and Iraq have intermediate rates of 14% and 12%, respectively (7). A meta-analysis estimated the prevalence of DV in Iran to be 66%, with regional variations: Seventy percent in the east, 75% in the south, 62% in the west, and 59% in both the north and central regions (8). A study in Gorgan, Iran, reported that about 52% of couples experienced DV, with bilateral violence at 25%, man-to-woman violence at 19.6%, and woman-to-man violence at 7.5%. Psychological aggression and sexual coercion were the most common forms of violence (9).

A 2020 study highlighted that different levels of DV (individual, interpersonal, and community) result in varying perceptions of DV-related factors. Culture and traditions influence DV (10), and on an interpersonal level, some individuals view self-defense as a means of protection (11), while others use violence to establish power and control, leading to coercive and manipulative behavior (1). Individual factors such as personal adjustment, psychosocial resources, attitudes towards gender roles, and sociodemographic characteristics also influence violence (12). A systematic review found that self-efficacy, normative beliefs, confidence in avoiding negative behavior, and coping skills can effectively reduce interpersonal violence (13).

Emotion regulation is a multidimensional construct that plays a role in the etiological models of DV, inhibiting and disinhibiting DV perpetration. Emotion regulation refers to an individual’s ability to control or adjust emotions, with explicit ER involving conscious techniques and implicit ER operating without conscious monitoring (14). Emotion regulation is becoming a crucial component of interventions designed to reduce DV risk (4). Deficits in ER are a significant factor in DV (11), with a meta-analysis showing a slight to moderate correlation between ER and DV perpetration in both males and females (4). Individuals struggling with ER difficulties, such as non-acceptance of emotional responses and impulse control issues, are more likely to engage in DV (11).

Given the high incidence of DV and its detrimental effects, healthcare professionals must identify, support, and care for victims while implementing intervention programs to prevent the cycle of violence. Despite the necessity of improving prevention efforts and evidence that IPV can be prevented, governments have not made sufficient progress in eliminating partner violence. Increasing research in this field may bring greater attention to this critical issue. In light of inconsistent findings from previous studies (4, 11, 15, 16) regarding the link between DV and ER, a new study was undertaken to establish the nature of this association.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between ER and DV among couples.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

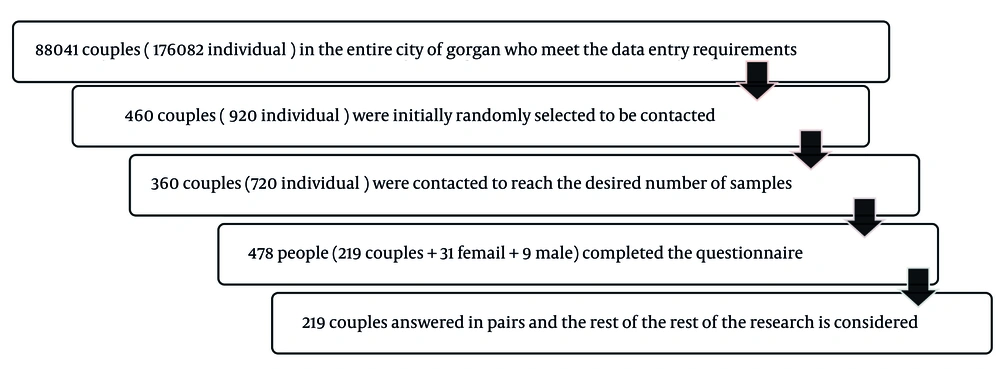

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted from April to November 2023, involving 219 healthy women aged 20 to 49 in Gorgan, Iran, and their current healthy monogamous spouses. Eligible couples were those with at least one year of marriage, living together, and having access to smartphones and the internet. Women who were pregnant or in the postpartum and menopausal periods were excluded from the study. In this study, based on the study results of Guzmán-González et al. (r = 0.21) (17), with a confidence level of 0.95 and a test power of 0.8, the sample size was calculated to be 175 couples (350 individuals). To account for a potential 20% non-cooperation rate in online conditions, the sample size was increased to 219 couples (438 individuals). Participants were selected using a random number table without replacement (Figure 1).

After the research was approved, and the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology and the Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences granted permission (ethical code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1401.599 and grant no. 113164), mobile phone numbers of participants were obtained from the electronic health record. The research participants were selected using a table of random numbers through simple random sampling without replacement. The inclusion criteria comprised healthy monogamous couples who had been married for at least two years, lived together, and were literate in reading, writing, and using mobile phones and the internet. Exclusion criteria included pregnant and menopausal women, women up to 42 days postpartum if not lactating, breastfeeding women up to 6 months postpartum, and women who were about to divorce. Couples who did not complete the research tools were also excluded. All participants were contacted via phone and informed about the study’s objectives. Consent was obtained digitally by participants pressing a button provided in the written forms. Participants were then sent a link to complete the online tools separately.

3.2. Research Tools

The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) and Conflict Tactics Scale-2 (CTS-2), developed by Straus et al. in 1973 and 1996, respectively, based on Adam’s conflict theory (1965) (18, 19), consist of two parts: Domestic violence and negotiation domains. This questionnaire is unique because it measures both the perpetrator and victim simultaneously and has been used in multiple contexts (20). The CTS-2 comprises 78 items. Each couple must complete 39 odd items (33 perpetrator items and six negotiation items) and 39 even items (33 victim items and six negotiation items) to obtain a complete assessment. Scores are computed separately for the victim domain, perpetrator domain, and negotiation. The internal consistency reliability of the original version of the CTS-2 scales ranged from 0.79 to 0.95, and the scale was found to be valid conceptually and methodologically (18). The administration time of the original version of CTS-2 is 10 - 15 minutes (18).

To investigate the occurrence of DV, the original version of CTS-2 is scored dichotomously. The frequency of DV and four sub-domains — psychological aggression, injury, sexual coercion, and physical assault during the past year — is categorized from 0 to 7. Categories 1 and 2 indicate the number of times the incident occurred, i.e., once or twice in the past year. For categories 3 to 5, the midpoint of the category is coded. For instance, category 3 (3 - 5 times) is coded as 4, category 4 (6 - 10 times) is coded as 8, and category 5 (11 - 20 times) is coded as 15. Category 6, which indicates more than 20 times, should be coded as 25. If there was no abuse in the previous year, category 7 is given a score of 0. The negotiation scoring (0 - 25) is the same as CTS-2 (18).

A psychometric study conducted on 395 samples (206 females, 189 males) found that the Persian version of the CTS-2 had appropriate reliability, validity, and factor structure (Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.66 to 0.86) for the Iranian population and is an efficient research tool. The coding and scoring of the Persian version of CTS-2 are similar to the original version (21).

The Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) is a self-report measure developed to assess relevant difficulties in ER. The original version of DERS (36 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 to 5, ranging from rarely to almost always) is widely used in different populations and languages. It is a comprehensive and brief scale with sound psychometric properties, such as reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93), validity, and factor analytic structure (22). Eleven items (1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 10, 17, 20, 22, 24, and 34) are rated inversely. The scale comprises six factors: Non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to ER strategies, and lack of emotional clarity (23). The reliability of the Persian version of DERS was found to be 0.90 in a psychometric study of the Iranian population. Higher scores indicate greater difficulties in ER (23).

The demographic form included education, jobs, ethnicity, and drug use of both women and men, and reproductive information for women (gravidity, parturition, abortion, child death, live child, and stillbirth number). Online written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the research objectives. The Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences approved the study (IR.GOUMS.REC.1401.599). None of the couples who experienced DV were willing to receive counseling services.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The study utilized SPSS version 19 for data analysis from couples who completed the tools. Mean and standard deviation were used to describe quantitative traits, while frequency distribution tables were employed to describe qualitative traits. The Spearman correlation test was used to investigate the hypothesis of a correlation between DV and ER among couples, with a significance level set at 0.05.

4. Results

In this study, 219 couples from Gorgan, Iran, participated, and 40 couples (31 men and 9 women) were excluded due to incomplete completion of scales (Figure 1). The duration of marriage among the couples ranged from 2 to 31 years. The majority of the women were homemakers (53%), and 3% of the men were unemployed. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the couples and the reproductive characteristics of the women.

| Variables | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic variable | ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| Persian | 173 (79) | 169 (77.2) |

| Turkmen | 9 (4.1) | 7 (3.2) |

| Baloch | 10 (4.6) | 13 (5.9) |

| Other | 27 (12.3) | 30 (13.7) |

| Education | ||

| Below high school diploma | 27 (12.3) | 40 (18.2) |

| High school diploma | 83 (37.9) | 56 (25.6) |

| University degree | 109 (49.8) | 123 (56.2) |

| The economic status b | ||

| Not good at all | 6 (2.7) | 6 (2.7) |

| Not good | 39 (17.8) | 40 (18.3) |

| Average | 106 (48.4) | 108 (49.3) |

| Good | 51 (23.3) | 49 (22.4) |

| Very good | 17 (7.8) | 16 (7.3) |

| Drug abuse | ||

| No | 176 (80.4) | 105 (47.9) |

| Yes | 40 (18.3) | 97 (44.3) |

| Rehabilitation | 3 (1.3) | 17 (7.8) |

| Nationality | ||

| Iranian | 216 (98.6) | 214 (97.7) |

| Afghan | 3 (1.4) | 5 (2.3) |

| Reproductive variable | ||

| Gravidity | ||

| 0 | 66 (30.1) | - |

| 1 | 60 (27.4) | - |

| 2 | 52 (23.7) | - |

| 3 ≤ | 40 (18.8) | - |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 74 (33.8) | - |

| 1 | 59 (26.9) | - |

| 2 | 51 (23.28) | - |

| 3 ≤ | 35 (15.99) | - |

| Abortion | ||

| 0 | 186 (84.9) | - |

| 1 | 20 (9.1) | - |

| 2 ≤ | 13 (6) | - |

| Living child | ||

| 0 | 69 (31.5) | - |

| 1 | 62 (28.3) | - |

| 2 | 53 (24.2) | - |

| 3 ≤ | 35 (16.0) | - |

| Dead child | ||

| 0 | 203 (92.7) | - |

| 1 | 10 (4.6) | - |

| 2 ≤ | 6 (2.8) | - |

Demographic Characteristics of Couples and Reproductive Information of Females, Gorgan, Iran a

The mean scores of DV and its four domains in men and women are shown in Table 2. According to the mean scores obtained, women, like men, were perpetrators of DV overall and in the four domains (injury, sexual coercion, physical assault, and psychological aggression) based on the perpetrator scale of CTS-2. Similarly, men, like women, were victims of DV overall and in all its domains (injury, sexual coercion, physical assault, and psychological aggression) based on the victim scale of CTS-2. The results indicated that the mean score for women in the injury domain was less than 1, suggesting that women were not victims of violence in this area (Table 2).

| DV and Sub-scales | Range of Scale | Range of Study | Perpetrator Scale | Victim Scale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | P-Value b | Total | Male | Female | P-Value b | |||

| Injury | 0 - 42 | 0 - 42 | 1.13 ± 3.31 | 1.19 ± 3.83 | 1.06 ± 2.69 | 0.828 | 1.00 ± 2.97 | 1.21 ± 3.67 | 0.79 ± 2.04 | 0.251 |

| Sexual coercion | 0 - 49 | 0 - 49 | 5.88 ± 5.70 | 6.06 ± 6.12 | 5.69 ± 5.27 | 0.633 | 5.95 ± 5.69 | 5.92 ± 5.96 | 5.97 ± 5.42 | 0.628 |

| Physical assault | 0 - 84 | 0 - 80 | 4.89 ± 8.97 | 5.26 ± 10.50 | 4.51 ± 7.13 | 0.898 | 4.97 ± 8.95 | 5.60 ± 10.66 | 4.35 ± 6.79 | 0.585 |

| Psychological aggression | 0 - 56 | 0 - 56 | 10.25 ± 9.12 | 10.19 ± 9.61 | 10.31 ± 8.61 | 0.437 | 10.58 ± 9.15 | 10.97 ± 9.89 | 10.19 ± 8.34 | 0.788 |

| DV | 0 - 273 | 0 - 226 | 22.50 ± 22.24 | 22.70 ± 25.26 | 21.58 ± 18.87 | 0.613 | 21.5 ± 22.24 | 23.70 ± 25.80 | 21.30 ± 17.97 | 0.766 |

| Negotiation | 0 - 42 | 0 - 42 | 24.08 ± 1013 | 23.85 ± 10.08 | 24.30 ± 10.20 | 0.639 | 24.34 ± 10.25 | 23.86 ± 10.23 | 24.81 ± 10.27 | 0.338 |

The Mean Scores of Domestic Violence and Its Sub-scales in Couples, Gorgan, Iran a

The mean scores of ER and its subscales in couples are shown in Table 3. As seen in Table 3, both men and women experienced difficulties in ER overall and in all six domains (non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to ER strategies, and lack of emotional clarity).

| ER and Sub-scales | Range of Scale | Range of Study | (Mean ± SD) | P-Value a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | ||||

| Non-acceptance of emotional responses | 6 - 30 | 6 - 30 | 5.82 ± 4.69 | 5.68 ± 4.83 | 5.96 ± 4.55 | 0.285 |

| Difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior | 6 - 30 | 5 - 25 | 9.51 ± 3.85 | 9.47 ± 4.04 | 9.55 ± 3.66 | 0.752 |

| Impulse control difficulties | 6 - 30 | 6 - 30 | 11.14 ± 4.90 | 10.91 ± 5.03 | 11.36 ± 4.78 | 0.397 |

| Lack of emotional awareness | 6 - 30 | 6 - 30 | 19.86 ± 3.66 | 19.82 ± 3.76 | 19.90 ± 3.56 | 0.929 |

| Limited access to ER strategies | 6 - 30 | 8 - 40 | 10.90 ± 5.67 | 10.62 ± 5.78 | 11.19 ± 5.57 | 0.123 |

| Lack of emotional clarity | 6 - 30 | 5 - 25 | 10.15 ± 3.25 | 10.15 ± 3.33 | 10.14 ± 3.17 | 0.909 |

| ER | 36 - 180 | 36 - 180 | 67.39 ± 18.93 | 66. 67 ± 19.34 | 68.11 ± 18.53 | 0.314 |

The Mean Scores of Emotion Regulation and Its Sub-scales in Couples, Gorgan, Iran

The Spearman rank correlations between DV and ER among couples are presented in . As shown in Table 4, difficulties in ER did not have a significant relationship with DV among perpetrators in both men and women. The results of the correlation test indicated that the relationship between difficulties in ER and DV was not significant (Table 4).

The Spearman Rank Correlations Between Domestic Violence and Emotion Regulation of Couples

5. Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the relationship between ER and DV in couples. The study concluded that women and men were similarly responsible for perpetrating DV. Moreover, the findings revealed that both men and women were subjected to victimization. A study reported concurrent IPV at 13% in low and lower-middle-income countries (24). Another study in the southwestern United States found that, on average, women reported 15 incidents of violence from their partners annually, while men reported 19 incidents. Approximately 22.8% of men reported that their violence was in self-defense more than 100% of the time, whereas only 10% of women reported their violent behavior as self-defense more than 100% of the time (25). These results contradict the feminist theory that highlights women as victims and men as perpetrators of violence. Domestic violence against men is a serious concern that poses a significant threat to their health and well-being and is increasingly recognized as a public health issue. A mixed-studies systematic review using nine electronic databases, searched from each database’s inception until January 2023, stated that men who are victims of DV often struggle to disclose and report their abusive experiences, remaining stuck in the loop of violence and encapsulated in predicament abusive relationships (26).

The difference between the results of this study and other studies could be attributed to the inclusion of both men and women, as well as the study’s focus not being exclusively on one gender. Another possible factor is that the couples in the study have been living together for some time, allowing them to become familiar with each other’s traits and have sufficient time to express themselves. Additionally, cultural norms in this region may lead both men and women to acknowledge being either perpetrators or victims of violence more openly.

This study showed that difficulty in ER in men and women was similar. In contrast, a study conducted in 2023 revealed gender differences in cognitive and affective strategies during intrapersonal ER among university students in China (27). According to another study conducted in England, women consistently utilized a greater number of strategies than men and demonstrated more flexibility in their implementation (28). A study in the Mexican population found significant differences between women and men in ER strategies, concluding acceptance, mindfulness, rumination, limited access to ER strategies, and interference in goal-directed behaviors (29). Another study suggested that women tended to use most ER strategies (problem-solving, self-blame, social support, and emotional expression) more often than men and more flexibly. However, women tend to use self-blame more than men because they are more likely to view their emotions as the result of something internal rather than something specific to that situation. Nevertheless, they note that quantitative differences in the use of ER strategies do not necessarily imply qualitative differences in ER effectiveness and implementation across contexts (28). Similarly, another study stated that women may employ a frontal top-down control network to down-regulate negative emotion, while men may redirect attention away from the negative stimulus by using posterior regions of the ventral attention network (30).

The differences in the results of this study compared to other research can be attributed to the fact that the participants were cohabitating couples. This close living arrangement allowed them to develop a deep understanding of each other, become familiar with their emotional triggers for the emergence of violence, anticipate their partner’s emotions, and synchronize their own emotions with their partner’s. Additionally, these differences could result from cultural and background disparities in how couples handle conflicts.

This study showed no significant relationship between difficulty in ER and DV among both male and female perpetrators and victims. Consistent with this study, research has shown that ER strategies used to regulate emotions are not effective in preventing DV (31). In contrast, a study has shown that in American healthy young adults, adaptive ER strategies play a significant role in reducing the incidence of DV, while maladaptive ER strategies are an important factor in understanding the prevalence of such violence in the Mexican population (29). The study found that women who engage in rumination and focusing are more likely to experience IPV. Meanwhile, men who have limited access to ER and impulse control difficulties are also at greater risk of committing DV (29).

The variations in findings between the current study and others could be attributed to differences in cultural and participatory contexts. Additionally, it’s worth noting that the couples cohabited during this study, enabling them to better understand each other’s emotional and behavioral patterns and interactive styles, which in turn may help prevent inappropriate interactions and ultimately reduce the occurrence of DV.

The study did not include couples who did not have smartphones. Domestic violence is a sensitive and taboo subject, and the study subjects may not have accurately reflected reality. To address this limitation, the research samples were assured of the confidentiality of the information, and the research tools were sent separately to the couples. Given that this study focused on DV, the perpetrator’s couple may have influenced the results related to the victim’s couple. To minimize this limitation, each couple was contacted separately, and the questionnaires were sent separately.

One of the most important limitations is that this is a descriptive study; to find the relationship between variables, stronger studies such as cohort or case-control studies are needed. It is suggested that more studies be conducted to conceptualize and determine other elements related to DV.

5.1. Conclusions

The difficulty in ER did not have a significant relationship with DV among perpetrators and victims. These findings differed from the research hypothesis and defied expectations, presenting an opportunity for raising new questions that future researchers can explore to shed more light on the topic. The findings of this study may not be fully generalizable to other populations due to the demographic and cultural characteristics of the participants. To improve generalizability, future research should replicate this study in different cultures, communities, and sample groups, employing longitudinal and comparative methodologies to validate the results. These findings contrasted with some previous research, indicating that more research may be needed to reconcile these differences. Additionally, qualitative studies may be necessary to address the discrepant findings.