1. Background

Increasing or decreasing fertility rates directly impact the age structure of any society. A continuous rise or fall in fertility rates can lead to an imbalance in the population's age structure. In Iran, the fertility rate has dramatically decreased from about seven children per woman in the early 1980s (1) to 1.68 children per woman in 2019 (2). This transition represents the fastest and most significant drop in fertility rates globally, considered both abnormal and exceptional. Over the past three decades, a rapid decline in fertility rates, combined with a substantial rise in life expectancy, has led to the rapid aging of Iran's population. Data indicate that Iran is the second fastest aging country in the world (3). If this population trend continues, it will result in a population size below the replacement level and increased aging in the coming decades.

Factors affecting the fertility rate can be investigated at both micro and macro levels. Micro-level factors are divided into personal and interpersonal categories. Personal factors include expanded women's education, participation in the labor market, personality traits, personal attitudes and preferences, reproductive knowledge, and physical and mental fitness. Interpersonal factors encompass stable relationships with spouses and other significant individuals. The macro level includes supportive policies, medical advancements, and socio-cultural and economic factors (4). Empirical evidence shows that many macroeconomic variables affect the fertility rate in a society. The most important variables are age, women's education, marriage age, income, household savings level, inflation rate, and economic growth (5). Therefore, according to social science experts, particularly demographers, the fertility rate is influenced by a combination of social, economic, political, cultural, biological (6), and individual factors.

Women's education is the only variable that directly affects the fertility rate. Entering university and pursuing higher education impacts fertility both indirectly, through changes in individual attitudes and the formation of modern viewpoints, and directly, by raising the age of marriage and consequently delaying childbearing. Additionally, women's social participation and their involvement in social affairs are crucial variables influencing changes in fertility rates among Iranian women (6).

In the past, many women were deprived of work opportunities due to their roles in housework and had limited access to education and employment compared to men. Today, women in many countries have equal access to education. However, to take full advantage of these opportunities, they may feel compelled to delay or reduce childbearing. In recent years, kindergartens located in offices and hospitals have been abolished, and medical science considers fertility after age 35 risky for both mother and child. Therefore, the increasing age of first marriage results in women having less time for childbearing. Even if they wish to have more children, they may not be able to achieve this, leading to a decrease in fertility rates (7).

Alderotti et al. used meta-analytic techniques to synthesize European research findings, suggesting that employment instability has a significant negative effect on fertility (7). New theories identify factors that determine the compatibility of women's career and family goals as key drivers of fertility. These include family policy, cooperative fathers, favorable social norms, and flexible labor markets (8). Behrman and Gonalons-Pons show that women's wage employment is negatively correlated with total fertility rates, although this finding holds mainly for nonagricultural employment (9).

Many women desire financial and economic independence and prefer to work outside the home. Given that childbearing involves housework and child-rearing responsibilities, leading to potential loss of job opportunities outside the home, they may delay having children or lack the desire to have children altogether. Various cultural, social, economic, and demographic factors have significantly contributed to the reduction in fertility rates in Iran over the past decades.

Population policies should be designed based on scientific and local evidence. Conducting research in different cities can help guide these policies. One policy consideration to address the decline in fertility rates is understanding employment and related factors' impact on fertility.

2. Objectives

Since this relationship has not been investigated in Fereydunkenar city, we decided to examine the relationship between women's employment and their decision to get pregnant among married women receiving services from health centers in Fereydunkenar.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This study is cross-sectional and descriptive-analytical and was conducted from April to September 2023.

3.2. Samples

The research community comprised married women of reproductive age who received services from the health centers of Fereydunkenar city. A convenience sampling method was employed to select the samples. To determine the required sample size for the study, considering a decision to get pregnant prevalence of 68.2% based on a previous study in Iran (10), a confidence level of 95%, and a precision of 0.05, it was determined that a minimum of 334 people should be sampled.

The formula used to calculate the sample size:

The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: Having informed consent to participate in the study, being married, being in the reproductive age group (15 - 50 years) (11, 12), having no infertility (defined as the failure to establish a clinical pregnancy after 12 months of regular and unprotected sexual intercourse) (13) or diseases that lead to infertility, and completely completing the data collection form.

3.3. Instruments

The data collection tool was a researcher-created questionnaire. The first part of the questionnaire included 24 questions on demographic and employment characteristics, while the second part contained 10 yes/no questions related to the reasons for not wanting to get pregnant among working women. To determine content and form validity, the questionnaire was reviewed by 4 expert gynecologists, 3 family medicine specialists, 2 midwives, 1 psychologist, 1 epidemiologist, 1 biostatistics expert, and 1 occupational health expert. Its reliability was checked using Cronbach's alpha coefficient method, yielding a coefficient of 0.98. The questionnaires were completed independently by the participants.

3.4. Statistical Analyzes

To determine the relationship between qualitative variables, the Chi-square test was used. Variables with a P-value of less than 0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the final model. Multivariate logistic regression with a backward elimination approach was then employed to model the independent variables (demographics and job components) and determine their relationship with the dependent variable, which is the decision to get pregnant or not. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (Ethics Code: IR.MAZUMS.IMAMHOSPITAL.REC.1402.021).

Ethical considerations in this study included obtaining permission to conduct the research, securing approval from the university and the health centers involved, ensuring voluntary participation, not interfering with participants' responses, maintaining confidentiality and privacy of the data, and obtaining permission to publish the findings. The study also adhered to the principles of respecting authors' rights by properly citing all sources used.

4. Results

4.1. Frequency of Pregnancy Decisions and the Relationship with Women's Employment

In the present study, among the 334 women investigated, 135 (40.4%) decided to get pregnant, with a 95% confidence interval of 35.11 - 45.90, while 199 (59.6%) did not. In terms of occupation, 261 women (78.1%) had a job, and 73 women (21.9%) did not. As shown in Table 1, the frequency of pregnancy decisions among working women was 36%, compared to 56.2% among non-working women (P = 0.002). Being employed doubles the likelihood of not wanting to get pregnant and have children.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or range.

b Chi-square = 9.61, P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

c Reference group.

4.2. Factors Associated with Pregnancy Decision Based on Univariate Analysis

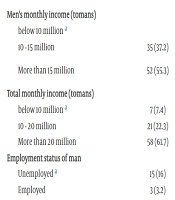

In working women, the relationship between age and the desire to get pregnant did not show statistical significance. According to the results of the present study, educational qualifications and the desire to get pregnant also did not show a significant relationship. Additionally, factors such as age at marriage, the interval between marriage and the first child, the husband's monthly income, total household income, the husband's employment status, the woman's willingness to work, history of abortion, history of illness in the previous child, and the presence of help in child care did not show a statistically significant relationship. However, other variables such as the duration of marriage, number of children, and desire to migrate were significantly related to the desire to get pregnant (Table 2).

| Variable and Classification | Number of Desires to Get Pregnant (%) | (OR) | (95% CI) | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||

| 15 - 20 b | 1 (1.1) | 1 | - | 0.86 |

| 21 - 30 | 44 (46.8) | 0.63 | 0.05 - 7.24 | 0.71 |

| 31 - 40 | 37 (39.4) | 0.9 | 0.07 - 10.32 | 0.93 |

| 41 - 50 | 12 (12.80) | 1.75 | 0.14 - 20.99 | 0.65 |

| Education | ||||

| Diploma and under diploma b | 38 (40.4) | 1 | - | 0.5 |

| Associate degree | 11 (11.7) | 0.42 | 0.15 - 1.13 | 0.08 |

| Bachelor | 38 (40.4) | 1.06 | 0.60 - 1.86 | 0.83 |

| Masters and PhD | 7 (7.4) | 1.89 | 0.74 - 4.82 | 0.18 |

| Marriage age (y) | ||||

| 15 - 20 b | 26(27.7) | 1 | - | 0.2 |

| 21 - 30 | 59 (62.8) | 1.02 | 0.58 - 1.82 | 0.92 |

| 31 - 40 | 9 (9.6) | 0.42 | 0.14 - 1.26 | 0.12 |

| 41 - 50 | - | - | - | - |

| Duration of marriage (y) | ||||

| 5 > b | 44 (46.8) | 1 | - | 0.04 |

| 5 - 10 | 30 (31.9) | 1.4 | 0.75 - 2.61 | 0.28 |

| 11 - 20 | 13 (13.8) | 4.41 | 2.13 - 9.14 | 0.001 |

| 20 < | 7 (7.4) | 2.32 | 0.78 - 6.14 | 0.08 |

| Number of children | ||||

| 0 b | 45 (47.9) | 1 | - | 0.02 |

| 1 | 33 (35.1) | 2.57 | 1.40 - 4.72 | 0.002 |

| 2 | 11 (11.7) | 6.07 | 2.76 - 13.34 | 0.001 |

| 2 < | 5 (5.3) | 3.6 | 1.18 - 10.95 | 0.02 |

| Distance between marriage and first child (y) | ||||

| 1 ≥ | 62 (66) | 1 | - | 0.01 |

| 2 | 12 (12.8) | 2.75 | 1.33 - 5.70 | 0.006 |

| 3 | 13 (13.8) | 1.46 | 0.68 - 3.12 | 0.32 |

| 4 | 3 (3.2) | 3.58 | 0.97 - 13.14 | 0.06 |

| 5 ≤ | 4 (4.3) | 3.31 | 1.05 - 10.40 | 0.04 |

| Men's monthly income (tomans) | ||||

| Below 10 million b | 35 (37.2) | 1 | - | 0.65 |

| 10 - 15 million | 52 (55.3) | 1.13 | 0.65 - 1.94 | |

| More than 15 million | 7 (7.4) | 2.41 | 0.97 - 5.96 | 0.06 |

| Total monthly income (tomans) | ||||

| Below 10 million b | 21 (22.3) | 1 | - | 0.42 |

| 10 - 20 million | 58 (61.7) | 0.82 | 0.43 - 1.53 | 0.53 |

| More than 20 million | 15 (16) | 1.58 | 0.71 - 3.50 | 0.25 |

| Employment status of man | 0.42 | |||

| Unemployed b | 3 (3.2) | 1 | - | |

| Employed | 91 (96.8) | 0.58 | 0.15 - 2.19 | |

| A man's desire towards his wife's employment | 0.1 | |||

| No b | 13 (13.8) | 1 | - | |

| Yes | 81 (86.2) | 0.56 | 0.28 - 1.12 | |

| History of abortion | 0.86 | |||

| No b | 64 (68.1) | 1 | - | |

| Yes | 30 (31.9) | 1.04 | 0.61 - 1.79 | |

| History of illness in the previous child | 0.31 | |||

| No b | 87 (92.6) | 1 | - | |

| Yes | 7 (7.4) | 1.59 | 0.64 - 3.94 | |

| Willingness to migration abroad | 0.002 | |||

| No | 78 (83) | 1 | - | |

| Yes | 16 (17) | 2.66 | 1.42 - 4.97 | |

| Presence of help in taking care of the child | ||||

| Nurse b | 11 (11.7) | 1 | - | 0.53 |

| Kindergarten | 20 (21.3) | 0.79 | 0.30-2.05 | 0.63 |

| Parents b | 46 (48.9) | 0.85 | 0.36 - 1.97 | 0.7 |

| Without help | 17 (18.1) | 2.12 | 0.84 - 5.34 | 0.11 |

a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

b Reference group (it is a class of each variable in which the chance of not wanting to get pregnant is calculated in the face of each of the variable classes compared to the reference class).

In Table 3, most of the working women who wanted to get pregnant had freelance jobs (63.8%) and the majority had permanent jobs (75.5%). The monthly income of women desiring pregnancy was below 10 million (74.5%), and they had contract status in terms of employment (16%).

Regarding the average daily working hours and the distance from residence to work, there was a statistically significant difference between working women who wanted to get pregnant and those who did not (P = 0.02). Women working 7 hours or less per day (67%) and those living within 5 kilometers of their workplace (64.9%) were more inclined to have children.

| Variable and Classification | Number of Desires to get Pregnant (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Type | 0.004 | |||

| Freelance job b | 60 (63.8) | 1 | - | |

| Employee | 34 (36.2) | 1.43 | 0.85 - 2.42 | |

| Steady job | 0.56 | |||

| Yes b | 71 (75.5) | 1 | - | |

| No | 23 (24.5) | 1.53 | 0.73 - 1.76 | |

| Women's monthly income (tomans) | ||||

| Below 10 million b | 70 (74.5) | 1 | - | 0.22 |

| 10 - 15 million | 20 (21.3) | 1.63 | 0.89 - 2.97 | 0.1 |

| More than 15 million | 4 (4.3) | 1.63 | 0.49 - 5.42 | 0.42 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Official b | 12 (12.8) | 1 | - | 0.45 |

| Contract | 3 (3.2) | 2.08 | 0.49 - 8.85 | 0.31 |

| Contractual | 15 (16) | 0.83 | 0.32 - 2.15 | 0.71 |

| Committed to serving | 2 (2.1) | 2.6 | 0.49 - 13.87 | 0.26 |

| Corporate recruitment | 2 (2.1) | 1.56 | 0.27 - 8.97 | 0.61 |

| Non-employment | 60 (86.3) | 0.8 | 0.37 - 1.72 | 0.57 |

| Daily working hours | 0.02 | |||

| Less than or equal to 7 b | 63 (67) | 1 | - | |

| Greater than 7 | 31 (33) | 1.87 | 1.10 - 3.16 | |

| Distance from residence to workplace (km) | 0.008 | |||

| Less than or equal to 5 b | 61 (64.9) | 1 | - | |

| Greater than 5 | 33 (35.1) | 2.01 | 1.19 - 3.38 |

a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

b Reference group (it is a class of each variable in which the chance of not wanting to get pregnant is calculated in the face of each of the variable classes compared to the reference class).

4.3. Factors Associated with Pregnancy Decision Based on Multivariate Analysis

Based on univariate analysis, six variables were included in the final model: Duration of marriage, number of children, willingness to migrate, type of job, daily working hours, and distance from residence to work. The results of multivariate logistic regression are shown in Table 4.

| Variable and Classifications | Beta Coefficient | OR and 95% CI | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of children | |||

| 0 c | - | 1 | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 0.92 | 2.59 (1.36 - 4.93) | 0.004 |

| 2 | 1.72 | 6.0 (2.47 - 12.7) | 0.001 |

| < 2 | - | - | - d |

| Willingness to migrate | 0.001 | ||

| No c | - | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.05 | 3.23 (1.64 - 6.36) | |

| Daily working hours | 0.02 | ||

| Less than or equal to 7 c | - | 1 | |

| Greater than 7 | 0.66 | 1.95 (1.10 - 3.43) | |

| Distance between residence and workplace (KM) | 0.04 | ||

| Less than or equal to 5 c | - | 1 | |

| Greater than 5 | 0.60 | 1.82 (1.03 - 3.35) | |

| Constant | -1.08 | 0.33 (-) | 0.001 |

a Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 (8) = 6.05, P-value = 0.64.

b P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

c Reference group (it is a class of each variable in which the chance of not wanting to get pregnant is calculated in the face of each of the variable classes compared to the reference class).

d Due to the small number of samples in this class of variables, the analysis was not performed.

Having one child compared to having no children increases the chance of not wanting to get pregnant by 2.59 times (OR = 2.59, CI 95%: 1.36 - 4.93, P = 0.004). Having two children increases the odds of not wanting to get pregnant by six times compared to having no children (OR = 6.00, CI 95%: 2.47 - 12.70, P = 0.001). Additionally, the desire to migrate increases the chance of not wanting to get pregnant by 3.23 times (OR = 3.23, CI 95%: 1.64 - 6.36, P = 0.001). Two other variables that remained significant in the final model were job components. If the distance from the place of residence to the workplace is more than 5 km, it increases the chance of not wanting to get pregnant by 1.82 times (OR = 1.82, CI 95%: 1.03 - 3.35, P = 0.04), and if the working hours are more than 7 hours a day, it increases the chance of not wanting to get pregnant by 1.95 times (OR = 1.95, CI 95%: 1.10 - 3.43, P = 0.02).

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between married women's employment and their decision to become pregnant. Additionally, this study aimed to assess the influence of factors such as the number of children, economic status, educational status, spouse's occupation, type of women's occupation, distance from residence to work, and the presence of help in child care on married women's decision to become pregnant. The results showed a negative linear correlation between women's employment and the desire to get pregnant. Based on the odds ratio obtained, there is a statistically significant relationship between being employed and delaying the decision to get pregnant. The number of children and the desire to migrate were significant variables related to the desire to get pregnant. Working hours, distance from residence to work, and type of job (freelancer or employee) also showed a statistically significant relationship with the desire to get pregnant. If the distance from residence to work is more than 5 kilometers, the chance of delaying the decision to get pregnant increases by 1.82 times, and if the working hours are more than 7 hours a day, it increases the chance of delaying the decision to get pregnant by 1.95 times. Having one child increases the chance of delaying the decision to get pregnant by 2.59 times compared to having no children. Having two children compared to having no children increases the chance of delaying pregnancy by six times. Additionally, the desire to migrate increases the chance of delaying pregnancy by 3.23 times.

In the study by Nasrabad et al., it was shown that having a modern gender attitude and the woman doing child-related tasks alone increases the interval between the first and second birth. In contrast, having an education less than a diploma reduces the interval between the first and second birth. An egalitarian gender attitude also causes a delay in the birth of the second child (6).

The results of this study show that if the distance from the place of residence to the workplace is more than 5 km, the chance of not wanting to get pregnant increases by 1.82 times, and if the working hours are more than 7 hours a day, the chance of not wanting to get pregnant increases by 1.95 times. In the study by Guner et al., it was shown that uncertainty created by dual labor markets, the coexistence of temporary and open-ended contracts, and the indexability of work schedules are crucial to understanding low fertility. They documented that temporary contract are associated with a lower probability of first birth. With Time Use data, they also showed that women with children are less likely to work in jobs with split shift schedules. Such jobs have a long break in the middle of the day and present a concrete example of indexable work arrangements and the fixed time cost of work (14).

In a study conducted by Kim T. (15) in Korea, which aimed to evaluate factors influencing pregnancy intention among women of reproductive age, it was shown that the age of women giving birth to their first child increases with the year of birth of the participants. These findings indicate that recent generations tend to postpone pregnancy until later ages. In the above study, weekly working hours were the most important predictors of pregnancy intention. The chance of pregnancy with weekly working hours of 40 to 45 hours is almost 2 times higher than the chance of pregnancy with working hours of less than 40 hours or more than 45 hours. Working 35 to 40 hours per week is significantly associated with an increase in the probability of pregnancy, suggesting an optimal spectrum of working hours for predicting pregnancy (15).

The results of the present study have shown that having one child compared to not having children increases the chance of not wanting to get pregnant by 2.59 times, and having two children compared to not having children increases the chance of not wanting to get pregnant by six times.

The study by Sharif Nia et al. (16) identifies several social factors affecting pregnancy behavior, such as mother's employment, age of marriage, number of children, access to contraceptives, living conditions, family income, type of acquaintance and marriage with a spouse, women's independence in the family, urban or rural status, degree of industrialization, social development, ethnic and cultural beliefs and customs, and societal views on the average number of family members. Economic problems, uncertainty about future security, shifting priorities, uncertainty about the continuation of life, fear of becoming a parent, lack of support, diminishing religious beliefs, social role modeling, and negative experiences all contribute to the conditions for choosing childlessness or having only one child.

In the study by Uddin, J. et al., it has been shown that women’s labor force participation is inversely associated with the actual and ideal number of children in Bangladesh. Compared to non-working women, women in the professional/skilled sector were more likely to have two or fewer living children and an ideal number of two or fewer children in the fully adjusted model (17).

Endale Kebede et al. show that both individual and community educational levels have a significant dampening impact on women’s fertility desires. Results indicate that at the individual level, women’s education has a stronger effect than household wealth and area of residence. The high levels of reported desired family size in rural parts of SSA are mainly a consequence of relatively lower levels of education. The impact of women’s education is even stronger at the community level. These findings are robust to alternative measures of fertility preferences and strengthen previous conclusions regarding the relationship between fertility and women’s education (18).

The results of the present study show that the desire to migrate increases the chance of delaying the decision to get pregnant by 23.3 times.

In the study by Xiong et al., it has been shown that factors such as the range of migration and the duration of migration are related to the decision to have children. The differences in culture, lack of familiarity with the new environment, and lack of stability in the new life contribute to migration delaying the decision to have children (19).

In the study by Baghaei Sarabi and Moazzi Khoraeim (20), it has been shown that migration affects fertility. Social relations between members of a society can influence the values and norms related to reproductive behavior, such as the number of children, all aspects of childbearing such as marriage, interest in having children, and organizing attitudes towards stimuli for regulating fertility.

5.1. Conclusions

According to the results of this study, being employed doubles the chance of not wanting to get pregnant and have children. Duration of marriage, number of children, and desire to migrate were significant variables related to the desire to get pregnant. Increasing the distance from the place of residence to the workplace, if it is more than 5 kilometers, also increases the chance of delaying the decision to get pregnant. Additionally, as the number of children increases, the probability of delaying the decision to have more children increases. The possibility of migration similarly increases the chance of delaying having children.

5.2. Recommendations

Factors such as insufficient time and the cost of raising a child seriously affect the decision to have a second child. In designing policies to encourage childbearing, these significant obstacles should be addressed so that families who desire to have a second or more children are not deprived of this opportunity. Appropriate policies and long-term planning to resolve concerns and provide suitable socioeconomic conditions and employment with adequate income are necessary. Reducing working hours for working women, implementing shift work, stabilizing employment status, and considering support for working women's children, such as childcare facilities, can help to reduce the time between the first and second child and increase fertility levels.

Additionally, many cultural and attitudinal factors play a role in the timing of having children. Conducting training classes on reducing the time to have children after marriage can also be effective in increasing the desire to have children and success in this matter.

5.3. The Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The study addresses a problem that concerns policymakers and is one of the main issues in Iran. Studies in different cities are needed to help policymakers, and this study was conducted with that goal in mind. It examined employment alongside other demographic characteristics and made comparisons between working and non-working women. In the present study, 85 working women had a history of abortion, and 26 had a history of having a sick child, both of which can impact the decision regarding subsequent pregnancies.