1. Background

Work-related stress is widely recognized as one of the primary occupational risks that reduce job satisfaction and efficiency (1, 2). The level of stress experienced at work varies depending on the type of job (3). Healthcare professionals play a crucial role in the performance of healthcare systems and the achievement of national and international health goals, as they are responsible for protecting and enhancing patients' health (4). Nursing, in particular, is considered a highly stressful profession due to its nature and organizational demands (5).

Job satisfaction is defined as "the degree to which individuals appreciate their occupations" or "the subjective perception of how well one's job meets their needs" (6). Nurses' job satisfaction has a significant impact on the quality of care they provide (7). Job satisfaction levels among nurses differ across countries. Research shows that nurses in the United States report the highest job satisfaction (41%), while those in Germany report the lowest (17%) (8). In Korea, nurses also experience lower-than-average job satisfaction (9). In Iran, a large number of nurses report moderate to poor levels of job satisfaction (10). Despite global interest in nursing, studies on nurses' well-being and professional development are more common in developed countries than in developing ones (11). Numerous studies have found that nursing staff, especially those in general hospitals, experience high levels of occupational stress, which can be attributed to various factors (2, 12). Past research has also revealed a strong negative relationship between stress and job satisfaction among nursing professionals (13, 14).

Researchers continue to examine key factors that influence job satisfaction to enhance evidence-based theories and management strategies for nurses (15). Job satisfaction is shaped by a range of demographic, occupational, and organizational factors (16). Several studies have demonstrated a strong negative correlation between occupational stress and job satisfaction, indicating that high stress levels can increase nurse turnover and reduce the quality of patient care (17, 18).

Many studies have explored the elements that contribute to workplace stress. These researchers developed specific models of occupational stress, including the job demand-control-support (JDCS) model (19, 20). The JDCS model is particularly relevant for healthcare workers, especially nurses, due to the unique demands, responsibilities, and required levels of control in the nursing field (21). The JDCS model explains the connection between employee well-being and their engagement in active learning through three job features: Job demands, job control, and social support. The model predicts two distinct processes: When job demands are high, and control and social support are low, employee health is at risk, leading to job strain and related issues. This is known as the strain hypothesis, which has substantial evidence showing how demands, control, and support influence employee health and well-being, particularly in terms of emotional exhaustion (22).

Studies conducted in non-Western countries have also supported the JDCS model (23-25). Research has identified key factors that contribute to job satisfaction among nurses in developed countries. However, given the differences in healthcare systems and nursing roles between developed and developing nations, more research is needed in developing countries to understand the occupational factors that influence job satisfaction among nurses. Such insights would help healthcare managers improve organizational culture and enhance job satisfaction (20, 26).

The JDCS model is particularly applicable to nursing due to the profession's inherent demands and necessary control. Both the main and interaction effects of the JDCS model have been significantly correlated with job satisfaction. Given the disparities between healthcare systems in developed and developing countries, there is a critical need for additional research to identify occupational factors that influence nurse job satisfaction. Understanding these factors can help healthcare administrators implement strategies to improve organizational culture and nurse retention. Establishing a positive organizational culture is widely recognized as essential for fostering optimal working conditions. However, there has been limited research on how job demands, control, and social support impact nurse workplace stress within the Iranian healthcare system. This study aims to address this gap by investigating the relationship between job satisfaction and the factors of the JDCS model among Iranian nurses.

2. Objectives

There is a limited number of studies in Iran, a developing country, that scientifically investigate stress in the nursing profession. This suggests that the Iranian healthcare system has not fully addressed the conceptual effects of job demand, job control, and social support on nursing professionals. As a result, this research aims to fill that gap by identifying the relationship between job satisfaction and the various factors of the JDCS model among nurses working in public hospitals affiliated with Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Design

This cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the impact of various variables on nurses' job satisfaction in public hospitals. Data were collected between February 2022 and February 2023. The participants were nurses working in public hospitals affiliated with Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, located in a northern province of Iran. The inclusion criteria for the nurses were holding a bachelor's degree in nursing, having at least one year of full-time work experience, no second job, and no specific physical or mental health issues (based on self-report). The exclusion criteria included having a second job or having been hospitalized for mental health treatment. The sample size was determined using a single proportion calculation for the total population, with a 95% confidence interval, 90% test power, a proportion of 0.5, and a margin of error of 0.05. At least 784 samples were required, and 840 nurses were included in this study.

3.2. Survey Instruments

The following questionnaires were used to collect data. Information was gathered through a combination of self-report and a demographic survey, which included details about the respondents' age, gender, marital status, work situation, as well as educational and occupational backgrounds.

3.2.1. Job Content Questionnaire

In this study, we employed the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) to evaluate all aspects of the JDCS model. The JCQ is a self-assessment tool designed to measure the psychological and social characteristics of occupations. From the full version of the JCQ, 30 questions were selected to represent five dimensions that measure job stress. These dimensions were psychological job demands (5 items), social support (8 items), decision latitude or control (9 items), job insecurity (3 items), and physical job demands (5 items). Each JCQ item was rated on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree or never) to 4 (strongly agree or often). The results were interpreted according to the "JCQ User's Guide" (27). This questionnaire has been translated into multiple languages, including Persian, and the JCQ Center approved its use. Additionally, Cronbach's alpha was used to evaluate the reliability of the dimensions, with the psychological job demands and job insecurity scoring 0.60 and 0.27, respectively, and the other dimensions ranging between 0.76 to 0.87 (28).

3.2.2. Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured using the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), a widely recognized instrument for evaluating job satisfaction across various professions. The MSQ consists of 20 questions designed to measure intrinsic satisfaction (12 questions), extrinsic satisfaction (6 questions), and overall satisfaction (2 items). Intrinsic satisfaction relates to job conditions and how employees perceive various aspects of their work. Extrinsic satisfaction concerns environmental factors and how employees view work-related aspects outside the job environment. Participants completed the questionnaire using a five-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from "extremely dissatisfied" to "very satisfied" (29).

3.3. Data Analysis

The statistical analysis of the collected data was performed using SPSS 25 and AMOS 24. Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation (SD), range, and prevalence, were calculated to summarize the information. Additionally, structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized to investigate the relationships between the variables.

Initially, the model was developed based on a literature review. The methods for measuring variables, such as reflective indicators and combinations of latent variables, along with their relationships, were determined. Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypothesized relationships among the latent variables influencing job satisfaction. Structural equation modeling consists of two components: A measurement model, which demonstrates how latent variables are explained by observed variables (i.e., related survey questions), and a structural model, which shows how latent variables are interconnected.

Factor analysis was conducted to assess the validity of the model's structure. Collinearity among the questions was examined, and Cronbach's alpha (α) was calculated for each scale to assess internal consistency and reliability. Model fit was evaluated using several criteria, including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the χ²/df ratio (chi-square divided by degrees of freedom). Statistical significance was determined at the P < 0.05 level.

4. Results

According to the findings from the 837 nurses surveyed, the mean age was 33.89 ± 7.49 years, with an average employment experience of 6.89 ± 7.081 years. The majority of the participants were male (75.8%), and 77.3% were married, while 22.7% were single. Most of the participants held a bachelor's degree (84.5%), 4% had a master's degree, and 11.4% had a doctorate. Additionally, 86.8% of the nurses worked in shifts.

The results indicated that the Skewness and Kurtosis (used to assess the normality of quantitative data) were within the range of -3 and 3, confirming that the variables were normally distributed. Moreover, the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance coefficient (used to assess collinearity) were within acceptable limits, indicating no significant collinearity between the variables. Table 1 presents the mean ± SD scores for the sections of the JCQ, with skill discretion and decision authority earning the highest mean scores.

| Scales | Mean ± SD Scores | Minimum-Maximum Score | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skill discretion | 30.92 ± 10.34 | 10 - 56 | 0.280 |

| Decision authority | 30.82 ± 6.91 | 12 - 52 | 0.100 |

| Psychological job demands | 27.66 ± 10.23 | 6 - 52 | 0.317 |

| Physical job demands | 13.15 ± 6.03 | 5 - 25 | 0.183 |

| Job insecurity | 7.78 ± 1.49 | 4 - 12 | 0.055 |

| Supervisor support | 10.62 ± 4.1 | 4 - 20 | 0.169 |

| Coworker support | 10.74 ± 4.17 | 4 - 20 | 0.157 |

Cronbach's alpha for all variables exceeded 0.7, confirming the questionnaire's reliability for research purposes. AMOS software and the maximum likelihood (ML) model were used to analyze the initial model. The output revealed that the X²/df value for the degrees of freedom in the primary research model was 35.11, which was inadequate. The PCFI Index, another measure of model fitness, indicated that the model was not optimally fit (PCFI = 0.47). Table 2 provides fitness indicators for the primary and final research models.

| Model | RMSEA | PCFI | CFI | X2/df |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 35.11 |

| Final | 0.09 | 0.63 | 0.92 | 5 |

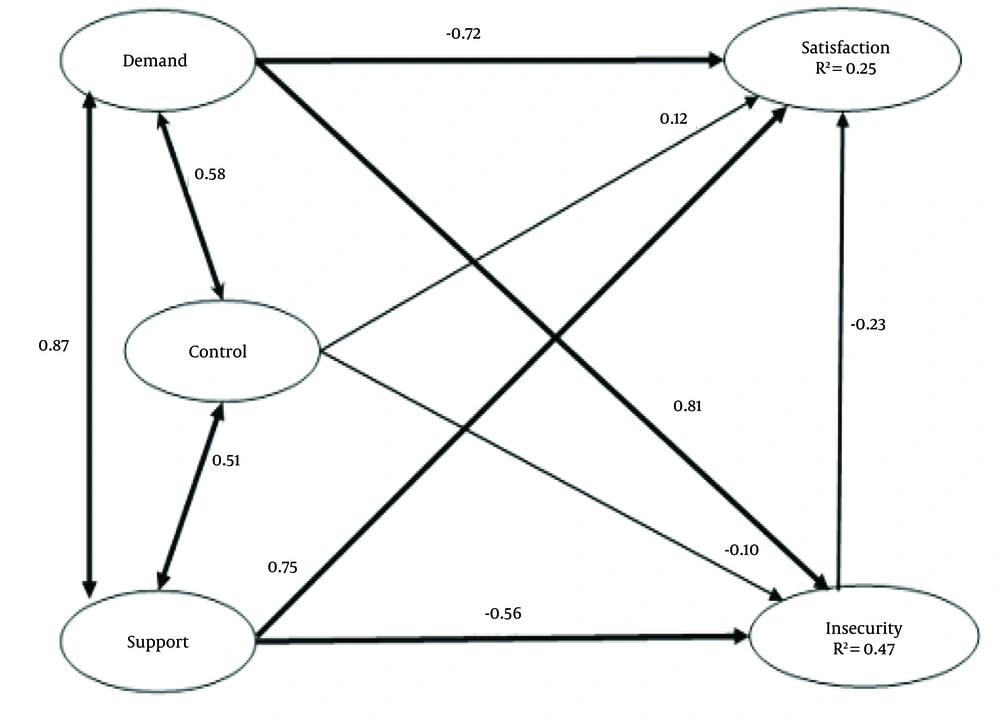

The findings revealed direct and positive relationships between demand and control (r = 0.58, P = 0.021), control and support (r = 0.51, P = 0.032), and demand and support (r = 0.87, P = 0.009). The directly standardized coefficients are shown in Figure 1, while Table 3 displays the standardized direct and indirect coefficients of the final model. According to Table 3, job insecurity was significantly and inversely correlated with both support (standardized = -0.56, P = 0.009) and control (standardized = -0.10, P = 0.020). Support had a positive direct effect on job satisfaction (standardized = 0.75, P = 0.008). Furthermore, as job demand increased, nurses' job satisfaction decreased.

| Variables | Standardized Direct | Bootstrapping 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value | Standardized Indirect Effect | Bootstrapping 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support on insecurity | -0.56 | -0.85, -0.33 | 0.009 | - | - | - |

| Support on Satisfaction | 0.75 | 0.49, 1.0 | 0.008 | 0.13 | 0.06, 0.24 | 0.003 |

| Control on insecurity | -0.10 | -0.17, -0.04 | 0.020 | - | - | - |

| Control on Satisfaction | 0.12 | 0.06, -0.23 | 0.012 | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.05 | 0.005 |

| Demand on insecurity | 0.81 | 0.62, 1.0 | 0.009 | - | - | - |

| Demand on Satisfaction | -0.72 | -1.18, -0.41 | 0.010 | -0.27 | -0.45, -0.12 | 0.005 |

| Insecurity on Satisfaction | -0.23 | -0.36, -0.10 | 0.007 | - | - | - |

5. Discussion

The JDCS model plays a significant role in influencing job satisfaction. In this study, it was found that the support and control nurses have over their jobs reduce insecurity and positively enhance job satisfaction. On the other hand, job demand reduces satisfaction and increases insecurity among nurses. High levels of insecurity were associated with a notable decrease in job satisfaction. Significant relationships were identified between demand and control, control and support, and demand and job satisfaction.

Specifically, social support had a direct positive effect on job satisfaction (standardized = 0.75, P = 0.008) and a negative impact on job insecurity (standardized = -0.56, P = 0.009). Similar findings have been observed in other studies. Harris et al. (30) found that task support and career mentoring were key factors of social support that greatly influenced job satisfaction. Orgambidez-Ramos and de Almeida (31) showed that high levels of work engagement, coupled with social support from colleagues and supervisors, were strong predictors of job satisfaction. When nurses are highly engaged in their work and receive social support from colleagues, their job satisfaction tends to increase even further (32).

Additionally, Lim (33) demonstrated that social support from colleagues and supervisors reduces job insecurity. The degree of support in the workplace can moderate the psychological well-being, self-worth, and financial confidence of employees (34). According to the indirect SEM method used in this study, social support can directly and indirectly affect job satisfaction by mediating job insecurity.

Job insecurity is inversely related to job satisfaction and employees' attitudes towards their work environment (35). Reisel et al. (36) found a negative correlation between job insecurity and satisfaction, further emphasizing that job insecurity affects work behaviors and emotions both directly and indirectly. Chronic stress associated with job insecurity can intensify over time, leading to higher absenteeism rates (37, 38).

Control, as a direct effect, has a negative impact on insecurity (standardized = -0.1, P = 0.02) and a positive impact on job satisfaction (standardized = 0.012, P = 0.012). This suggests that when nurses have greater control over their jobs, they feel less insecure and more satisfied. Job control significantly influences job satisfaction and the intention to remain at work (39). In a study by Abraham, job control was found to be a key factor in explaining differences in job satisfaction (40). Similarly, a 2017 study (41) demonstrated that job control has a considerable effect on employee satisfaction, as well as on reducing psychological distress and depression.

Job control enhances job security by giving employees a sense of autonomy and control over their work. When employees have more control over their job responsibilities and decision-making processes, they are better able to adapt to workplace changes, which helps them maintain their position within the company. Furthermore, having control over one's work can provide a sense of accomplishment and fulfillment. Employees who are able to make decisions about their work tend to feel more valued and respected by their employers. Additionally, job control allows for greater flexibility in scheduling and task prioritization, reducing stress and promoting a better work-life balance.

The presence of the variable "job insecurity" moderates the relationship between "Control" and "Job Satisfaction" (standardized = 0.02, P = 0.005). This means that the indirect and significant impact of "Control" on "Job Satisfaction" decreases when considering "job insecurity." A 2016 study found that while job demands and social support are linked to nurses' satisfaction at work, the connection between job demands and satisfaction was not affected by job control (42).

Job insecurity is a significant factor that can induce work-related stress, impacting both individual and organizational performance while lowering job satisfaction (43). It can lead to negative attitudinal responses, such as reduced job satisfaction, decreased commitment, and increased motivation to quit. Additionally, the perception of lacking control over circumstances is another element that contributes to job insecurity. Therefore, understanding how job control influences job satisfaction requires considering the effects of job insecurity (44).

Job demand, as a direct effect, has a positive influence on job insecurity (standardized = 0.81, P = 0.009) and negatively impacts job satisfaction (standardized = -0.72, P = 0.01). In line with the job demands-resources model, studies suggest that job performance is negatively affected by job insecurity, as it reduces work engagement. The adverse relationship between job insecurity and work performance weakens when employees contribute to and receive support related to job demands (45). Stress and anxiety can arise when employees feel their workload exceeds their capacity, leading to feelings of job insecurity. Job satisfaction may be influenced by perceived occupational stress caused by job demands, control levels, and the amount of social support (20).

Despite high levels of job demand, if someone feels overworked or underappreciated, they may believe their position is less secure. This could be due to concerns about burnout, lack of recognition or support, or a sense that their position is expendable if the demands become too much to handle. Also, a high level of high job demand can reduce job satisfaction among nurses. According to Hossein Abadi's research in 2021, higher levels of psychological and physical demands are negatively correlated with job satisfaction, consistent with the findings of this study (46). When job demands are high, employees may feel overwhelmed, stressed, and overworked, which can lead to decreased job satisfaction. Conversely, low job demand can result in boredom and a lack of fulfillment, also reducing job satisfaction. If employees feel overworked or underappreciated, their satisfaction with work and overall well-being may suffer.

The indirect SEM method showed that the demand variable, in addition to its direct effect on job satisfaction, indirectly affects it through job insecurity as a mediating variable (standardized = -0.27, P = 0.005). This means that as job demand increases, job insecurity grows, and job satisfaction decreases. High job demands may indirectly impact job satisfaction by increasing job insecurity, which can negatively affect employee productivity and health. However, acknowledging contributions, fostering a resilient work environment, and providing constructive feedback can help improve job satisfaction. Job insecurity acts as a mediator in the relationship between demand and job satisfaction, where insecure employees may experience less satisfaction, engagement, and trust in their employer (47).

"Job insecurity" may also moderate the impact of job demand on job satisfaction by emphasizing the negative aspects of high job demands. Employees who feel insecure about their jobs may be more sensitive to job-related stress and anxiety, which can further decrease their job satisfaction. Insecurity, as a direct effect, negatively influences job satisfaction (standardized = -0.023, P = 0.007). A high level of job insecurity results in lower job satisfaction among nurses. Prior studies have shown an inverse correlation between job satisfaction and job security requirements (48).

This research, while conducted under controlled conditions, has some limitations. First, self-reported questionnaires may introduce bias. Second, factors such as personality type were not considered. Third, the specific job may influence the model's results, which could vary in other positions. Future studies should consider factors such as personality type, employees' lifestyle, and work conditions, including shift work, awards, and wages.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that increasing social support and reducing job demands can significantly improve nurses' job satisfaction. These results suggest that investing in supportive programs for nurses and redesigning job tasks to reduce workload can decrease job stress, enhance workforce retention, and ultimately improve the quality of care. Hospital administrators can enhance nurses' job satisfaction by creating supportive work environments, providing necessary training, and offering opportunities for professional growth. Policymakers can also contribute by developing supportive policies and establishing new standards for nurses' work environments.