1. Background

With the rapid advancement of digital technology, pornography has become increasingly accessible, affordable, and anonymous, contributing to a significant global rise in consumption (1-3). Many individuals, particularly young adults, utilize pornography as a supplementary source of sexual information, especially in contexts lacking comprehensive sex education (4, 5). While 'pornography addiction' remains widely used, the term 'problematic pornography use (PPU)' has gained increasing recognition in academic literature due to its more nuanced clinical and conceptual implications (6). Accurately assessing the prevalence of compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) and obtaining reliable epidemiological data presents substantial methodological challenges. Current research indicates pornography consumption rates among partnered individuals range from 71 - 92% for men and 34 - 83% for women in romantic relationships (7, 8). A study conducted among university students in Sistan and Baluchistan, Iran (mean age = 22.35 years) revealed that 74% of male and 35% of female participants reported pornography use within the previous year (9). Research indicates that pornography consumption correlates with both beneficial and adverse sexual outcomes. On the one hand, some studies demonstrate potential positive effects, including enhanced sexual knowledge and arousal facilitation. Conversely, other research identifies negative associations, such as the development of unrealistic sexual expectations, diminished sexual satisfaction, and compromised intimate relationship functioning (10, 11). Motivations for pornography consumption are multifaceted, encompassing sexual curiosity, emotional regulation, sensation-seeking, and boredom alleviation (12). These differential motivations may mediate pornography's effects on both relational dynamics and individual psychosocial well-being (13). While extensive research has examined pornography use in Western contexts, cultural factors critically influence its perception and psychosocial impacts. In conservative sociocultural environments like Iran, where religious values profoundly shape sexual norms, pornography's effects may diverge substantially from patterns observed in more permissive societies. However, significant gaps remain in empirical investigations of this phenomenon within Iranian culture. This paucity of research is particularly pronounced regarding married women, a population for whom sexual discourse remains culturally constrained (14-16).

2. Objectives

Given these cultural specificities and empirical lacunae, the present study examined the relationships between pornography consumption patterns (including frequency of use and motivational drivers) and sexual compatibility among Iranian women.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This online cross-sectional study examined married Iranian women living in Tehran between 2022 and 2023. The research framework was developed through expert consultations with three reproductive health specialists during the design phase. Given the sensitive nature of sexual behavior research, we employed an online survey methodology to: (1) Minimize social desirability bias inherent in face-to-face data collection, and (2) enhance participant comfort when disclosing personal information. After rigorous development and testing by the research team, we implemented a Persian-language survey via the PorsLine platform, which underwent multiple validation rounds before deployment.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

This study included women aged 18 - 49 years with sexual activity for at least six months. Participants were also required to demonstrate a willingness to engage in sexual health research. Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) Current pregnancy or lactation; (2) diagnosed chronic debilitating conditions (e.g., multiple sclerosis, neurodegenerative disorders); (3) active chronic diseases (including but not limited to cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, or autoimmune disorders); (4) any diagnosed or self-reported mental health conditions; and (5) provision of incomplete or inconsistent survey responses. These criteria were established to ensure a homogeneous sample of generally healthy, sexually active married women while controlling for potential confounding medical and psychological factors.

3.3. Sample Size

Based on an analysis of pertinent studies, specifically Bothe et al. and Bridges and Morokoff (17, 18), along with the application of the subsequent formula, the estimated sample size was determined to be 725 individuals.

Since all participants with any history of pornography use were included in the study, the final sample size exceeded initial estimates. While our main outcome variable (sexual compatibility) remained within the originally projected sample size, the two secondary predictor variables (sexual function and sexual distress) were measured in this larger sample. A total of 725 participants were initially calculated based on standard parameters (α = 0.05, power = 80%, and expected correlation coefficient) and a review of similar studies to meet the requirements of our primary research objective. However, we deliberately expanded the sample size to strengthen the statistical power (to at least 95%) and reduce the significance level (to a maximum of 0.01). Therefore, we chose 1,421 participants to increase the accuracy and reliability of detecting significant associations, particularly for the two key predictor variables — sexual function and distress. Importantly, this expanded sample does not compromise the findings. On the contrary, reducing the sample size would likely lead to a smaller P-value and a more pronounced correlation coefficient (moving farther from zero), meaning the significant linear relationships identified would appear even stronger in a smaller sample.

3.4. Sampling

Sampling was conducted using a convenience method through online questionnaires (PorsLine) in collaboration with an online platform. The study employed a geographically stratified recruitment strategy by distributing questionnaires via the PorsLine online platform in partnership with 22 district-specific community networks across Tehran, Iran. This approach leveraged existing local associations, neighborhood social groups, and virtual community platforms to ensure broad demographic representation from all administrative districts. The multi-channel dissemination method facilitated access to diverse socioeconomic populations while maintaining the anonymity benefits of digital data collection, a particularly crucial consideration for sensitive sexual health research in Iran's cultural context. District-based peer networks were instrumental in achieving balanced geographic coverage, enabling recruitment beyond the limitations of conventional convenience sampling. During the questionnaire distribution, careful attention was given to ensure sampling from all demographic strata. To enhance the generalizability of the findings, a diverse sampling was undertaken from various social and demographic cohorts within Tehran, Iran.

3.5. Study Tools

Demographic data were collected using a comprehensive questionnaire assessing key variables, including age, education level, occupation, monthly sexual frequency, and pornography use characteristics (frequency and motivation).

Sexual function was evaluated using the 19-item Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), which measures six domains: Desire, subjective arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. Each domain is scored from 0 to 6 (where 0 indicates no sexual activity in the past 4 weeks), with domain totals multiplied by specific weighting factors. The total score ranges from 2 to 36, with higher scores indicating better sexual functioning. For the Persian version used in this study, Fakhri et al. established good reliability, reporting Cronbach's alpha coefficients ≥ 0.7 for all domains through internal consistency testing, along with demonstrated construct validity. Also, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) demonstrated good factorial validity for the proposed six-factor model (CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.06), supporting the measure's domain structure (19).

3.5.1. Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised

This is a self-report instrument consisting of 13 items assessing different aspects of sexual distress. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 ("never") to 4 ("always"), where higher total scores reflect greater sexual distress. The total score is derived by summing all 13 items. The scale demonstrates excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach's α ranging from 0.87 to 0.93. The CFA validated the instrument's structural validity, while a clinical cutoff score of ≥ 11 effectively differentiated between women with and without clinically significant sexual distress [AUC = 0.89, 95% CI (0.85, 0.93)] (20). The instrument's reliability was established by Azimi Nekoo et al. through both internal consistency (Cronbach's α > 0.7) and test-retest reliability (R > 0.7), demonstrating adequate psychometric properties for research use (21).

3.5.2. Hurlbert Index of Sexual Compatibility

This is a self-report tool used to measure the sexual compatibility of couples. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing higher sexual compatibility (22, 23). This instrument underwent comprehensive psychometric validation in Iran by Ahmadnia et al. The researchers established reliability through internal consistency analysis (Cronbach's α > 0.70) and confirmed face validity for all 24 original items. Quantitative content validity assessments demonstrated strong results, with all items exceeding minimum thresholds [content validity ratio (CVR) > 0.59; Content Validity Index (CVI) > 0.79] (24).

3.5.3. Pornography Use Motivation Scale

Developed to assess multifaceted motivations for pornography use, the scale comprises 24 items distributed across eight domains: Sexual pleasure (1, 9, 17), sexual curiosity (2, 10, 18), fantasy (3, 11, 19), boredom avoidance (4, 12, 20), lack of sexual satisfaction (5, 13, 21), emotional distraction/suppression (6, 14, 22), stress reduction (7, 15, 23), and self-exploration (8, 16, 24), with each domain represented by three items (17, 25). Pornography use frequency was operationalized as the average monthly consumption over the preceding three-month period. Participants responded to the standardized question: "On average, how many times per month did you view pornography in the last three months?" with responses recorded as a continuous numerical variable (17, 26). Each item is rated on a Likert scale (e.g., 1 = "Never" to 5 = "Always" or 1 - 7, depending on the study). Higher domain scores reflect a stronger endorsement of specific motivations for pornography use. For instance, elevated scores on the sexual pleasure subscale indicate primary motivation by arousal enhancement. Elevated scores on stress reduction or emotional distraction subscales may suggest clinically significant problematic use patterns. The questionnaire's validity was established through expert review by ten field specialists. For reliability testing, we conducted a pilot study (n = 50) that demonstrated strong internal consistency for both scales: The Pornography Use Motivation Scale (PUMS; α = 0.89) and the Pornography Use Frequency Scale (α = 0.85), as measured by Cronbach's alpha (27).

3.6. Ethical Consideration

Alborz University of Medical Sciences approved this study (IR.ABZUMS.REC.1401.197). Before participating in the research, participants provided informed consent virtually in the same space as the online platform. They were assured of the anonymity of their responses and the confidentiality of their information.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Frequency and percentage were used to describe qualitative variables, and mean and standard deviation were used to describe quantitative variables. We employed Spearman's correlation coefficients to assess bivariate relationships, followed by a two-stage regression analysis. First, univariate linear regression identified candidate variables (P < 0.20) for multivariable modeling. To optimize model fit, we applied backward elimination (exit criterion: P > 0.05), excluding variables exhibiting multicollinearity (VIF > 5). The final adjusted multiple linear regression model controlled for confounding effects. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (v.22), with statistical significance set at α = 0.05 (two-tailed).

4. Results

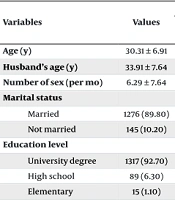

A total of 1,421 participants completed the FSFI and Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS) questionnaires, while 746 participants completed the Hurlbert Index of Sexual Compatibility (HISC). Table 1 shows participants' demographic characteristics.

| Variables | Values | Sexual Function | Sexual Distress | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Regression; β (SE), P-Value | Multiple Regression; β(SE), P-Value | Univariate Regression, P-Value | Multiple Regression, P-Value | ||

| Age (y) | 30.31 ± 6.91 | -0.09 (0.02), < 0.001 | -0.06 (0.02), < 0.001 | 0.08 (0.04), 0.051 | 0.08 (0.04), < 0.001 |

| Husband’s age (y) | 33.91 ± 7.64 | -0.08 (0.02), < 0.001 | - | 0.07 (0.04), 0.047 | - |

| Number of sex (per mo) | 6.29 ± 7.64 | 0.18 (0.02), < 0.001 | 0.16 (0.02), < 0.001 | -0.31 (0.04), < 0.001 | -0.27 (0.04), < 0.001 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 1276 (89.80) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Not married | 145 (10.20) | 0.67 (0.47), 0.15 | 0.83 (0.44), 0.06 | 1.58 (0.93), 0.09 | 0.83 (0.44), 0.06 |

| Education level | |||||

| University degree | 1317 (92.70) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| High school | 89 (6.30) | -2.21 (0.52), < 0.001 | -2.05 (0.49), < 0.001 | 2.75 (1.15), 0.02 | 1.96 (1.01), 0.07 |

| Elementary | 15 (1.10) | -0.21 (1.24), 0.86 | -0.30 (1.16), 0.80 | -0.43 (2.73), 0.87 | -0.54 (2.61), 0.84 |

| Husband’s education level | |||||

| University degree | 1159 (81.60) | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| High school | 207 (14.50) | -0.82 (0.36), 0.02 | - | 2.44 (0.79), 0.002 | - |

| Elementary | 55 (3.90) | -2.02 (0.70), 0.004 | - | 3.11 (1.45), 0.03 | - |

| Smoking | |||||

| Yes | 213 (15.00) | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| No | 1208 (85.00) | -1.12 (0.35), 0.002 | - | -0.19 (0.79), 0.81 | - |

| Regular menstruation | |||||

| Yes | 1042 (73.30) | Ref | - | Ref | Ref |

| No | 379 (26.70) | -0.95 (0.29), 0.001 | - | 3.04 (0.63), < 0.001 | 1.98 (0.61), 0.001 |

| Exercise | |||||

| Yes | 487 (34.30) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| No | 934 (65.70) | -1.49 (0.26), < 0.001 | -0.98 (0.25), < 0.001 | 2.47 (0.59), < 0.001 | 1.28 (0.57), 0.02 |

| Economic status | |||||

| High | 445 (31.30) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Moderate | 893 (62.90) | -1.19 (0.27), < 0.001 | -0.93 (0.26), < 0.001 | 2.31 (0.61), < 0.001 | 1.66 (0.59), < 0.001 |

| Low | 83 (5.80) | -2.85 (0.58), < 0.001 | -2.00 (0.55), < 0.001 | 7.01 (1.26), < 0.001 | 5.53 (1.22), < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: β, regression coefficient; SE, standard error; Ref, reference group.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

The average score of the studied participants on the HISC Questionnaire was 2.70 ± 0.74, and the average overall score on the PUMS Questionnaire was 6.23 ± 3.38. Regarding the eight items on the PUMS Questionnaire, the average of sexual pleasure was 8.38 ± 5.64, curiosity was 7.36 ± 4.33, fantasy was 6.27 ± 4.29, boredom avoidance was 5.57 ± 3.70, lack of sexual satisfaction was 5.72 ± 4.22, suppression (emotional distraction) was 4.93 ± 3.48, stress reduction was 5.11 ± 3.79, and self-exploration was 6.50 ± 4.24. In addition, the average of viewing frequency was 1.13 ± 0.48, duration of observation was 1.13 ± 0.53, watching pornography solitary was 2.09 ± 1.29, and watching pornography with husband was 1.24 ± 0.61. On the other hand, the average sexual function score is 16.07 ± 4.65, and sexual distress is 9.71 ± 10.61. The variables FSFI (β = -0.07, P = 0.21) and FSDS (β = 0.09, P = 0.14) did not exhibit statistically significant associations with pornography use in either the correlation or regression analyses; therefore, they were excluded from the final multivariate model focusing on pornography use. However, both variables were influenced by factors such as age, physical activity, and economic status. These findings should be interpreted with caution due to potential multicollinearity issues, which are further addressed in the limitations section.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants, along with the results of regression analyses for sexual function and sexual distress. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses identified several significant predictors of sexual function (FSFI), including frequency of sexual intercourse, age, education level, exercise habits, and economic status. Specifically, an increase in the number of sexual encounters was associated with a 0.16-point improvement in sexual function scores. Conversely, sexual function significantly declined with increasing age, with each additional year associated with a 0.06-point decrease. Women who engaged in regular physical activity demonstrated significantly better sexual function compared to those who did not. Similarly, lower economic status was associated with poorer sexual function. Moreover, women who reported no health-related or relationship problems had significantly higher sexual function scores than their counterparts. All findings were adjusted for potential confounding variables.

Regarding sexual distress, key influencing variables included frequency of sexual intercourse, age, irregular menstruation, exercise, and economic status. Increased frequency of sexual activity was associated with a significant reduction in sexual distress, with each additional sexual encounter correlating with a 0.27-point decrease in distress scores. In contrast, sexual distress increased with age, rising by 0.08 points for each additional year. Women with irregular menstrual cycles reported significantly higher levels of sexual distress compared to those with regular cycles. Additionally, lack of exercise was linked to elevated sexual distress, with non-exercising women reporting an average increase of 1.28 points in distress scores compared to those who exercised. Lower economic status and the presence of personal or relational problems were also associated with higher levels of sexual distress. These associations remained significant after adjusting for other variables in the model.

As presented in Table 2, all pornography use motives — except for sexual curiosity — were significantly associated with sexual compatibility. These motives included sexual pleasure, fantasy, boredom avoidance, lack of sexual satisfaction, emotional distraction or suppression, stress reduction, and self-exploration. Additionally, a statistically significant inverse association was observed between the frequency of pornography use and sexual compatibility at the 95% confidence level (Table 3). Specifically, higher frequency and longer duration of pornography consumption were both linked to lower levels of sexual compatibility. However, this association was not significant among women who reported watching pornography with their husbands. In contrast, a significant negative relationship emerged when pornography was consumed alone; that is, as the frequency of solitary pornography viewing increased, sexual compatibility significantly declined (P < 0.05).

| Compatibility | Sexual Pleasure | Sexual Curiosity | Fantasy | Boredom Avoidance | Lack of Sexual Satisfaction | Emotional Distraction or Suppression | Stress Reduction | Self-exploration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | -0.17 | -0.002 | -0.25 | -0.21 | -0.46 | -0.26 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| P-value | < 0.001 | 0.95 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Compatibility | Viewing Frequency | Duration of Observation | Watching Pornography Solitary | Watching Pornography with Husband |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | -0.14 | -0.11 | -0.16 | 0.03 |

| P-value | < 0.001 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | 0.47 |

5. Discussion

This study examined associations between pornography consumption patterns, including frequency and motivations, and sexual compatibility among Iranian women. Results revealed that higher frequencies of solitary pornography use significantly correlated with diminished sexual compatibility. Notably, pornography use exhibited no significant associations with sexual function or distress after covariate adjustment. These findings align with emerging research emphasizing contextual and individual factors. In a systematic review study, researchers found that pornography does not affect sexual function (28). Similarly, a large community survey emphasized that the frequency of pornography use has a weak association with sexual function (29). A study on sexual distress showed that pornography consumption does not lead to sexual distress and may even boost marital dynamics (30). In this regard, another study showed similar results and stated that pornography, when used transparently and mutually, does not affect sexual distress (31).

In line with the results of the present study, a study found that individual pornography use, especially when frequent, was associated with reduced intimacy and relationship satisfaction (32). Similarly, another study reported that solitary pornography use negatively predicted perceived sexual compatibility (33). These studies emphasize the importance of shared sexual experiences in sustaining sexual satisfaction and compatibility within couples. Perceived sexual compatibility is considered a strong predictor of sexual satisfaction and demonstrates that having mutual sexual understanding may outweigh merely mirroring sexual behaviors (34). Moreover, watching pornographic films alone, particularly on days of sexual activity with a partner, has been linked to reduced intimacy and greater sexual dissatisfaction (35). This highlights the role of mutual sexual understanding and shared sexual experiences as key factors in maintaining sexual satisfaction in committed relationships.

In contrast, pornography use within a couple, when done consensually, could create opportunities for improved dialogue and sexual preference exploration (13). However, pornography use motivated by sexual curiosity may yield potential benefits for partnered relationships. Such engagement could foster sexual exploration, amplify shared sexual activity, and cultivate heightened eroticism within dyadic contexts (30). By expanding sexual literacy, this practice might mitigate maladaptive affective responses, such as shame, guilt, or anxiety, thereby reducing sexual distress (36). Exposure to diverse sexual practices through pornography could further enhance sexual adaptability through two mechanisms: (A) normalization of diverse sexual repertoires, and (B) improved sexual responsiveness via cognitive-emotional priming. These processes may synergistically contribute to heightened physiological arousal, increased sexual desire, and improved overall sexual function, particularly when contextualized within the excitation-transfer paradigm of sexual motivation (37).

People who use pornography are not addicted to the content, but to the dopamine that is produced in dopaminergic pathways as a result of using pornography (4). Recent evidence indicates that exposure to pornography content may negatively influence perceptions of the physical attractiveness of sexual partners, as well as their sexual appeal and behaviors, ultimately impacting overall sexual satisfaction (28, 29). Also, sexual expectations can be affected by watching pornography and overshadowing the sexual relationship with his/her partner. People who watch pornographic content experience more excitement while watching pornography, while they experience low sexual arousal with their partners (30). Unrealistic expectations about appearance and performance may affect both individuals watching the pornography and their partner's sexual function, leading to an increase in sexual distress (31).

Several demographic and lifestyle factors were found to influence FSFI and Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R) among pornography users in Iranian women. Advancing age was linked to decreased sexual function and increased distress, likely as a result of physiological changes like hormonal fluctuations, which is in line with findings from Iran (Rasht) (2024), who found that older women had a higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction. Lower education levels were linked to poorer sexual function (38), which aligns with another study from Iran (Sari) (2020), showing that higher education improves sexual health awareness and resource access. Economic position emerged as an important predictor, with lower socioeconomic backgrounds related to inferior sexual performance and increased distress (39). Also, frequent exercise lowered distress and increased sexual function (40), supporting studies that show exercise improves physical fitness and lowers stress (41). According to another study, there appears to be a reciprocal relationship between the frequency of sexual activity and improved sexual function (42). The mentioned studies focused on the general population. However, our findings suggest that similar patterns exist among women with PPU. The effects of pornography use may interact with these demographic factors, potentially worsening sexual function and distress issues, indicating a need for more research comparing these two groups.

This study provides vital insight into the intricate connection between Iranian women's sexual compatibility and their usage of pornography, a group that has received little attention in this area. A strong community-based sample of 1,421 individuals from all 22 districts of Tehran is one of its methodological strong points, guaranteeing wide demographic representation and improved generalizability. A detailed examination of consumption patterns was made possible by the use of established, culturally appropriate tools and the incorporation of multidimensional criteria for pornography usage, such as frequency, duration, and reasons. Furthermore, by taking important confounding factors into account, careful correction for confounders like age, socioeconomic level, and physical activity enhances the validity of the results. Together, these design decisions establish the study as a noteworthy addition to our knowledge of the function of pornography in marriage dynamics in conservative cultural settings.

There are a number of limitations to this study. It is unclear whether the use of pornography has a direct effect on sexual compatibility or whether consumption patterns are driven by prior relationship dissatisfaction because the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Second, considering Iran's cultural sensitivities over sexual discourse, relying solely on self-reported measures of sensitive behaviors, such as the usage of pornography, may be vulnerable to memory and social desirability biases. Third, knowledge of how reciprocal actions could attenuate these correlations is limited due to the lack of dyadic-level data, such as partners' use of pornography or relational dynamics. Fourth, even with the inclusion of covariates like physical activity and socioeconomic status, unmeasured confounders may still exist. Lastly, a deeper investigation of how participants individually understand the function of pornography in their relationships is limited by the absence of qualitative insights.

5.1. Conclusions

This study identified two key patterns among married Iranian women. First, increased frequency of pornography use demonstrated a significant negative association with sexual compatibility, as did solitary consumption. Second, affect-regulation motivations, particularly emotional suppression and stress reduction, showed strong negative associations with compatibility. While pornography use exhibited no significant links to sexual function or distress outcomes, which were instead predicted by demographic and lifestyle factors, these findings highlight the relational risks of compensatory pornography use in conservative cultural contexts where open sexual communication remains constrained. They also emphasize the critical need for clinicians and sexual health professionals to evaluate both pornography use frequency and the motivations underlying consumption.