1. Context

HIV is a persistent and disabling illness caused by a retrovirus, which is transmitted and targets cellular immunity, resulting in HIV infection (1). Individuals with HIV have a weakened immune system, making them vulnerable to infections and ultimately leading to death. Current statistics from 2022 - 2023 indicate that approximately 39.9 million people are living with HIV globally (2, 3). Since the first reported cases, HIV has evolved into a major worldwide challenge for public health and the global economy. In Iran, 24,760 individuals with HIV have been identified, with a yearly mortality rate of 1,900 (4-6).

Currently, due to the increasing use of antiretroviral therapy (ART), the life span of individuals with HIV has increased. As with other long-term illnesses, individuals living with HIV are thought to experience a range of additional health issues, particularly those related to mental health. Based on the literature review, there is a higher occurrence of depression among those who are HIV-positive compared to the general population (7). According to a recent report, the rate of depression among people with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is two to three times higher than in the general population, with 40 to 60 percent of them experiencing symptoms of depression. This, in turn, reduces the effectiveness of ART medication and increases suicide rates (8, 9). Additionally, depression is believed to shorten the life span and reduce the quality of life for HIV-positive individuals. Moreover, depression weakens the immune system. On the other hand, individuals suffering from depression often do not adhere well to treatment plans, which increases the likelihood of severe complications and potentially fatal outcomes for those affected by both HIV and depression (10, 11).

2. Objectives

Therefore, given the regional disparities in the prevalence of depression among HIV/AIDS patients and the lack of a meta-analysis study in Iran, we decided to investigate the prevalence of depression among Iranians living with HIV/AIDS, with a focus on notable regional and gender-based variations, through a meta-analysis study. Our goal is to support future interventions and policies while providing a realistic picture of HIV-related mental health issues.

3. Method

3.1. Procedure for Searching

Without a time constraint until October 18, 2024, we searched both national and international databases, including PubMed/Medline, Web of Science, Embase, the Scientific Information Database (SID), Magiran, Medlib, Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar. We combined terms and variants of AIDS Virus OR AIDS Viruses OR Human T-Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type III OR Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Type III OR Lymphadenopathy-Associated Virus OR Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Virus AND Depression OR Depressive Symptom OR Emotional Depression AND Iran, using both controlled vocabularies and free-text words. To optimize the search queries, emphasis was placed on the unique features of each database. In addition to the electronic database search, the reference lists of the included articles and previous reviews were also scanned. Every stage of this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (12).

3.2. Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion

The following inclusion criteria were met by the studies: Original research conducted in Iran and published in either Persian or English. Case reports, study protocols, commentaries, letters, correspondence, and quasi-experimental studies that reported inaccurate prevalence calculations or figures were excluded.

3.3. Selection of Studies

Duplicate articles were eliminated after all records retrieved from various databases were exported to the EndNote reference manager. Subsequently, two authors (SHR and MH) independently screened the titles and abstracts to assess potentially relevant papers. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, and the full texts of the remaining studies were retrieved based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements that arose during the selection process were resolved by a third adjudicator (LA).

3.4. Data Extraction

Using a pre-prepared data abstraction form, the following elements were extracted from the selected articles: (1) Study characteristics: Author’s name, year of publication, study design, and geographic region; (2) sample characteristics: Sample size, age, and gender; (3) other variables: Addiction status, study quality, number of individuals with HIV/AIDS, number of individuals with depression, and the type of questionnaire used.

3.5. Evaluation of Quality

The selected papers were evaluated using the 22-item strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) research tool. Based on the criteria in this instrument, the relevant articles were categorized into three quality-based groups: Low (1 - 7), medium (8 - 16), and high (17 - 22). Additionally, two authors independently conducted the evaluation, and any potential conflicts were resolved through consultation with a third author (13). The agreement between the two investigators and their inter-rater reliability were assessed using the Kappa statistic, which yielded a kappa coefficient of 0.80.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

A random-effects analysis model was used to quantify the prevalence of depression in HIV/AIDS patients, taking into consideration the expected substantial heterogeneity between studies (14). The degree of heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic and Q-tests (15). Heterogeneity levels based on I² were categorized as follows: Low (25 - 50%), moderate (50 - 75%), and high (> 75%). Missing data were addressed using the imputation method.

To identify the sources of between-study heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted based on geographic region, gender, study year, addiction status, study quality, and the type of questionnaire employed. Sensitivity analysis was performed by sequentially excluding each study to assess the robustness of the pooled estimate.

In addition, Egger’s test and visual inspection of the funnel plot were used to evaluate publication bias (16). Data analysis was conducted using STATA software, version 14.

4. Result

4.1. Study Results and Characteristics

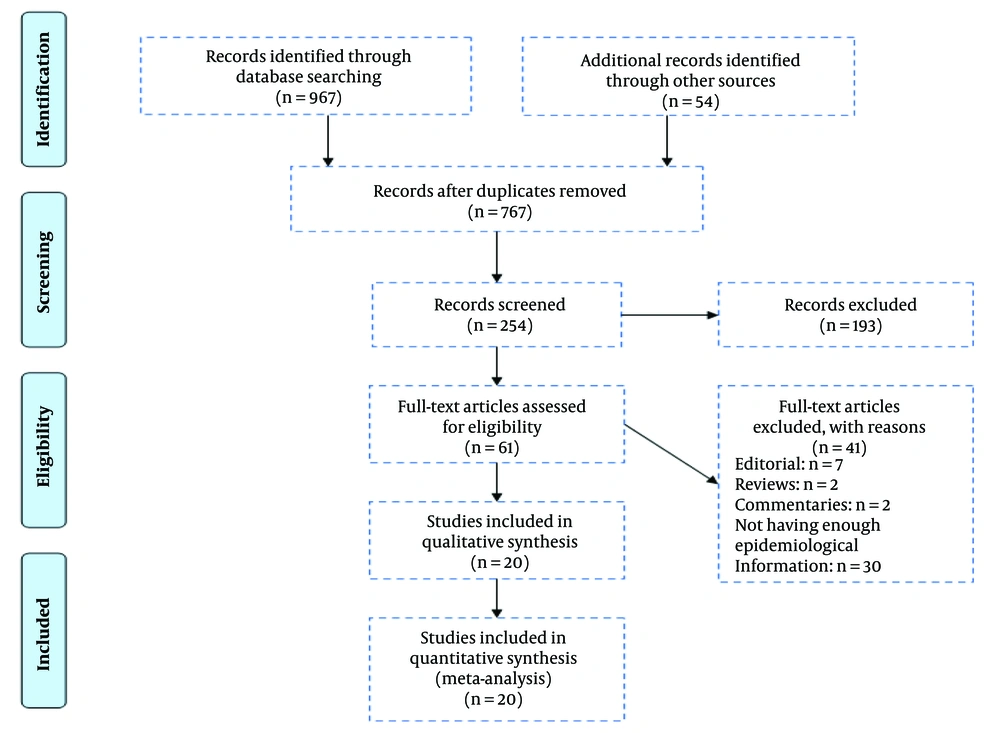

The search approach used to identify relevant articles is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Of the 1,021 publications initially identified, 959 were excluded as duplicates or deemed irrelevant based on their titles and abstracts. A full-text evaluation was conducted on the remaining 61 potentially eligible papers. Of these, 41 studies were excluded for the following reasons: Editorials (7), reviews (2), commentaries (2), and lack of epidemiological data (30).

Following a thorough full-text assessment, 20 articles that met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. A total of 4,471 participants were involved in the 20 included studies, with 766 from the Southeast, 95 from the South, 1,397 from the North, 951 from the West, and 1,185 from 15 Iranian provinces. Participants' ages ranged from 33.7 to 41.88, with a mean age of 37.1. Additionally, all included studies were cross-sectional in design. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the characteristics of each enrolled study.

| Author, Publication (Year) | Geographical Regions | Study Period | Sex | Age | Addiction Status | HIV/ADIS | Depression | Questionnaire Type | Depression in Female | Depression in Male | Study Quality | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amini Lari et al., 2013 (17) | Shiraz | NR | Male | 34.4 | No | 237 | 180 | BDI-II | - | - | Low | - | - |

| Moayedi et al., 2012 (18) | Bander Abbas | 2012 | Mix | 36 | Mixed | 95 | 69 | GHQ-28 | - | - | Moderate | 64 | 31 |

| Rezaee et al., 2013 (19) | Tehran | 2011-2012 | Mix | 35.9 | No | 100 | 68 | BDI | - | - | Moderate | 42 | 58 |

| Bidaki et al. 2012 (20) | Kerman | NR | Mix | 39.6 | No | 83 | 39 | CIDI | - | - | Low | 71 | 12 |

| Emadi-Kouchaka, 2006 (21) | Tehran | 2006-2007 | Mix | 37.9 | No | 199 | 81 | BDI-II | - | - | Moderate | 172 | 27 |

| Shakeri et al., 2005 (22) | Kermanshah | NR | Mix | NR | Mixed | 132 | 48 | NR | - | - | Low | - | - |

| Golestaneh 2012 (23) | Shiraz | NR | Mix | NR | Mixed | 44 | 11 | MMPI-2 test | - | - | Moderate | - | - |

| Sayad et al., 2007 (24) | Kermanshah | 2004 | Mix | 34.3 | Yes | 59 | 13 | SCL-90-R Questionnaire & diagnostic check list using criteria DSM- IV | - | - | Low | - | - |

| Bijani and Kazemifar, 2016 (25) | Qazvin | 2009-2014 | Mix | 33.7 | No | 77 | 26 | NR | - | High | 58 | 19 | |

| Mahboobi et al., 2020 (26) | Tehran | October and November 2019 | Mix | 39.81 | Mixed | 298 | 169 | DASS | - | - | High | 202 | 96 |

| Zareipour et al., 2021 (27) | Kerman | 2018 | Mix | 41.88 | Mixed | 122 | 88 | BDI-II | - | - | High | 65 | 57 |

| Ebrahimizadeh et al., 2019 (28) | Shiraz | 2013 | Mix | 38 | NR | 220 | 112 | BDI-II | - | - | Moderate | 129 | 91 |

| Shadloo et al., 2018 (29) | Tehran | 2012 - 2013 | Mix | 35.9 | Mixed | 250 | 86 | NR | 32 | 54 | High | 147 | 103 |

| Hamzeh et al., 2017 (30) | Kermanshah | 2015 | Mix | 38.53 | NR | 335 | 204 | BDI-II | 64 | 139 | High | 212 | 123 |

| Golrokhi et al., 2023 (31) | Tehran | January to September 2019 | Mix | (18 - 52) | NR | 100 | 68 | DASS | 34 | 34 | High | 58 | 42 |

| Ebrahimzadeh Mousavi et al., 2023 (32) | 15 provinces of Iran | April to August 2019 | Mix | 35.35 | Mixed | 1185 | 604 | DASS | - | - | High | - | - |

| Pasdar et al, 2019 (33) | Kermanshah | NR | mix | 36.97 | NR | 335 | 254 | BDI | - | - | High | - | - |

| Rasoolnezhad et al., 2018 (34) | Tehran | 2015 - 2016 | Mix | 37.29 | Mixed | 450 | 243 | GHQ-28 | 86 | 157 | High | 226 | 184 |

| Dovasaz-Irani et al., 2006 (35) | Ahvaz | 2004 | men | NR | Yes | 60 | 57 | BDI | - | - | Low | - | - |

| Mobaein and Farhadi Nasab 2010 (36) | Hamadan | NR | Mix | 38.25 | Yes | 90 | 71 | BDI | - | - | Moderate | 86 | 4 |

Summary of Included Studies on Prevalence of Depression in HIV/AIDS in Iran

4.2. Overview of Prevalence of Depression in Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome in Iran

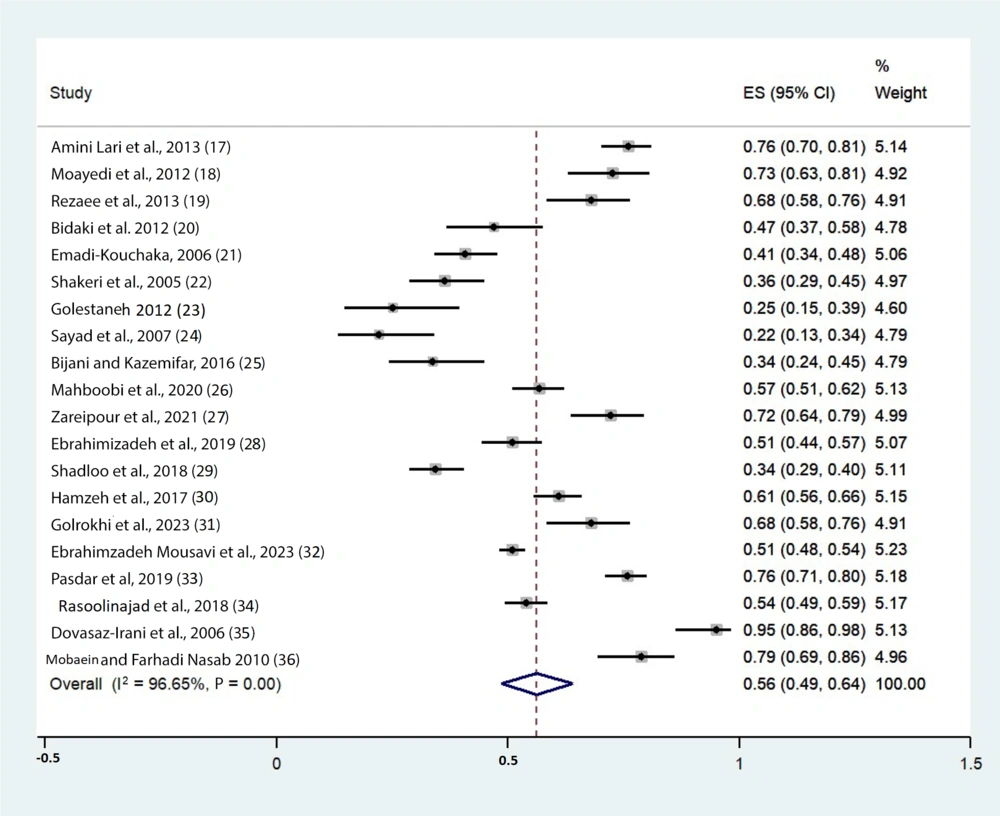

It was estimated that 4,471 Iranian HIV/AIDS patients suffered from moderate to severe depression overall. Data analysis using the random-effects model also revealed that the pooled prevalence of depression among HIV/AIDS patients was 56% (95% CI: 49% - 64%), with significant heterogeneity (P < 0.001) quantified at 96.65%. This high level of heterogeneity may be attributed to differences in measurement tools, regional variations, and the varying quality of the included studies (Figure 2).

4.3. Prevalence of Depression in Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome in Iran Based on Geographical Regions

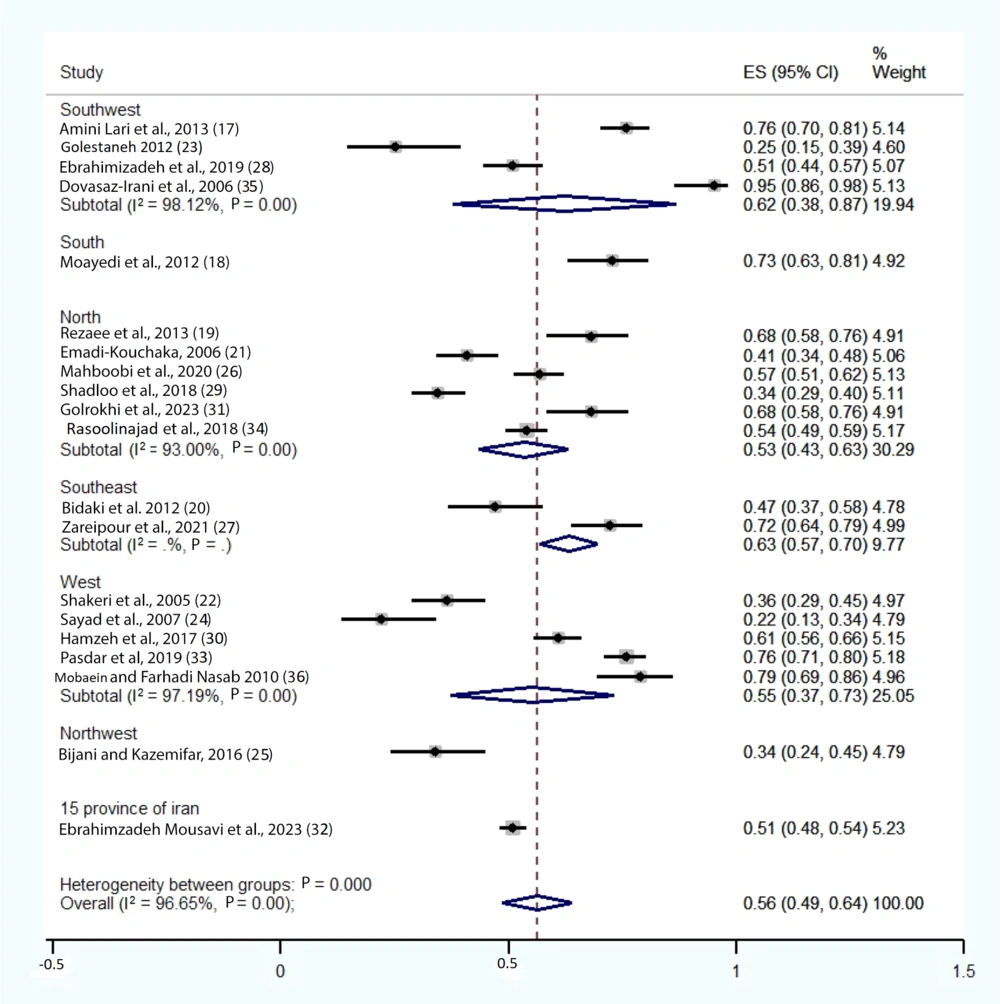

It is implied that the prevalence rate of depression in HIV/AIDS patients across different regions of Iran is as follows: Southwest – 62% (95% CI: 38% - 87%; I2 = 98.12%, P-value < 0.001), South – 73% (95% CI: 63% - 81%; I2 = 0, P-value = 0), North – 53% (95% CI: 43% – 63%; I2 = 93%, P-value < 0.001), Southeast – 63% (95% CI: 57% - 70%; I2 = 0, P-value = 0), West – 55% (95% CI: 37% - 73%; I2 = 97.19%, P-value < 0.001), Northwest – 34% (95% CI: 24% - 45%; I2 = 0, P-value = 0), and 15 provinces – 51% (95% CI: 48% - 54%; I2 = 0, P-value = 0), respectively (Figure 3).

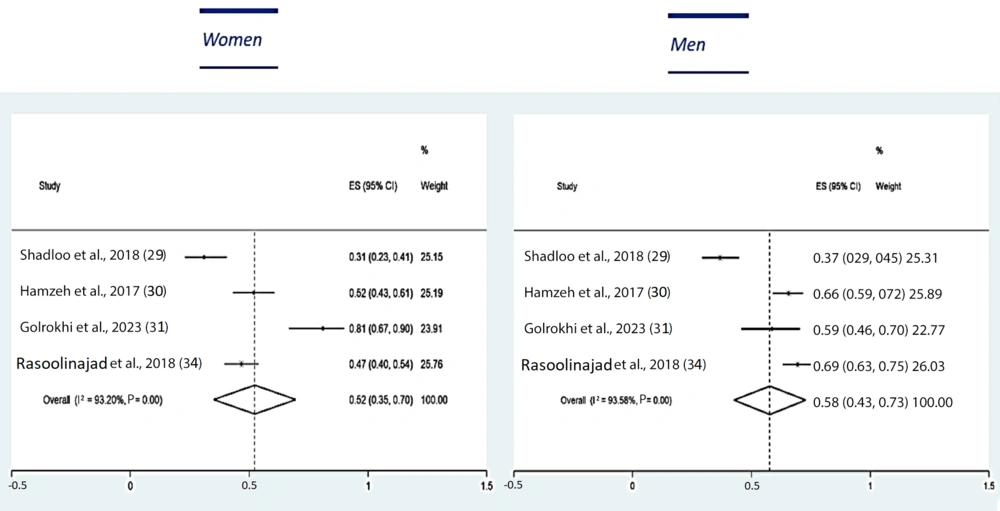

4.4. Prevalence of Depression in Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome in Iran Based on Gender

Four of the 20 selected articles focused on the prevalence of depression in men and women living with HIV/AIDS, with 71% of the participants being men. The results of the random-effects model analysis indicated that the prevalence of depression among men living with HIV/AIDS was 58% (95% CI: 0.43% - 0.73%; I2 = 93.58%, P-value < 0.001), while for women, it was 52% (95% CI: 35% - 0.70%; I2 = 98.20%, P-value < 0.001) (Figure 4).

4.5. Prevalence of Depression in Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome in Iran Based on Other Subgroups

The prevalence of depression was examined based on the type of questionnaire used, the addiction status of the patients, and the quality classification of the research, all of which are presented separately in Table 2.

| Variables | Number of Studies | ES % | 95%CI | I2 % | P (Heterogeneity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of questionnaire | |||||

| BDI | 9 | 0.69 | 0.58 - 0.79 | 96.17 | 0.001 |

| DASS | 3 | 0.58 | 0.49 - 0.66 | - | - |

| GHQ-28 | 2 | 0.58 | 0.54 - 0.62 | - | - |

| Other | 6 | 0.33 | 0.27 - 0.40 | 60.87 | 0.03 |

| Addiction status | |||||

| No | 5 | 0.53 | 0.36 - 0.71 | 95.80 | 0.00 |

| Yes | 3 | 0.66 | 0.27 - 0.95 | - | - |

| Mixed | 8 | 0.51 | 0.42 - 0.59 | 93.84 | 0.00 |

| NA | 4 | 0.64 | 0.53 - 0.75 | 92.77 | 0.00 |

| Quality type | |||||

| Low | 5 | 0.56 | 0.30 - 0.81 | 98.36 | 0.00 |

| Moderate | 6 | 0.56 | 0.42 - 0.71 | 94.58 | 0.00 |

| High | 9 | 0.56 | 0.48 - 0.65 | 95.43 | 0.00 |

Subgroup Analysis for Prevalence of Depression in HIV/AIDS in Iran

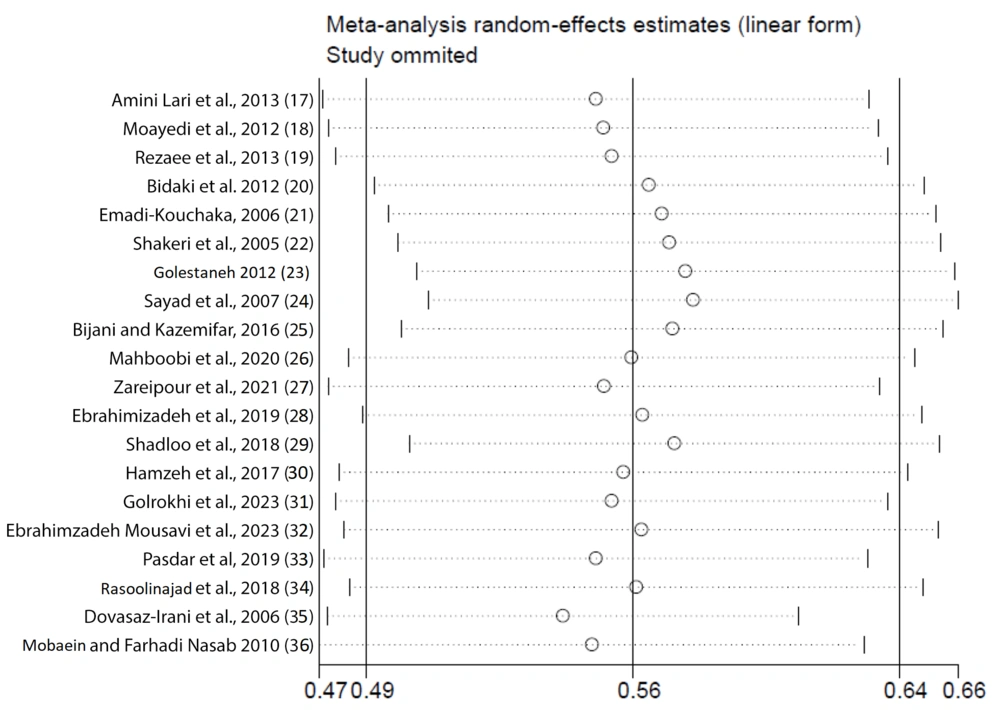

4.6. Sensitivity Analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis using the random-effects model to assess the impact of individual studies on the overall meta-analysis. The studies by Sayad et al., 2007 (24); Dovasaz-Irani et al., 2006 (35); and Golestaneh (23), 2012, if excluded, had the greatest influence on the results (Figure 5).

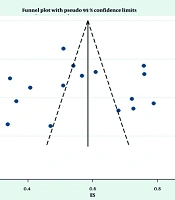

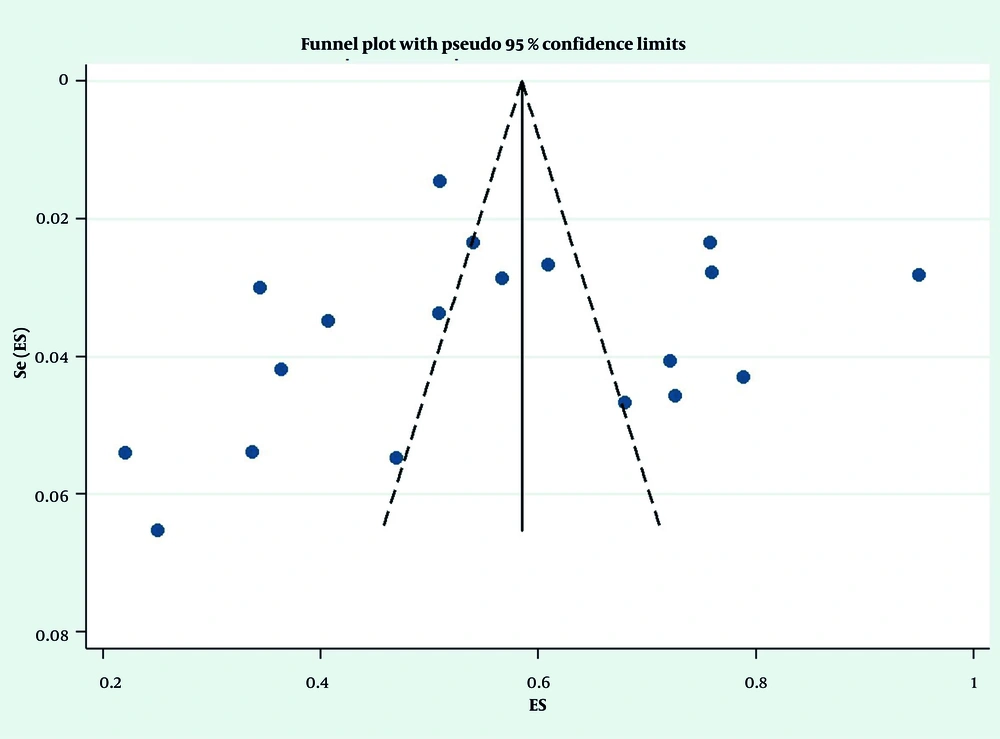

4.7. Publication Bias

Regarding the funnel plot diagram illustrating the prevalence of depression in individuals with HIV/AIDS, only two studies exhibited slight asymmetry; however, the overall diagram appears symmetrical, indicating no evidence of publication bias. Furthermore, based on the Begg’s and Egger’s tests, no publication bias was detected (Begg: P = 0.256; Egger: P = 0.683) (Figure 6).

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

This study showed that the pooled prevalence of depression among individuals with HIV/AIDS in Iran was 56%. Differences in study populations, methodologies, and regional factors contributed to the substantial heterogeneity of 96.65%. The occurrence of depression among individuals with HIV/AIDS varied significantly across different regions of Iran. The southern region had the highest percentage of cases at 73%, followed by the southeast and southwest regions at 63% and 62%, respectively. In contrast, the northwest region had the lowest occurrence rate at 34%, which is consistent with the study by Doosti-Irani et al. (37).

Various factors, such as socioeconomic conditions, access to healthcare services, and cultural attitudes toward mental health and HIV/AIDS, could influence these regional differences. Additionally, in the study by Rabeya et al., the significantly higher prevalence in southern Iran compared to the western and northern regions suggests potential disparities in mental health services, social support systems, or HIV-related stigma (38).

Findings also revealed that men with HIV/AIDS had a slightly higher prevalence of depression (58%) compared to women (52%). The prevalence of depression further varied depending on the type of questionnaire used and the addiction status of the participants.

5.2. Comparisons with the Existing Evidence

The current study's estimate of the prevalence of depression in the Iranian population with HIV/AIDS (56%), compared to that derived from a meta-analysis on the prevalence of depression in Iranian adolescents (34.26%), is 1.63 times higher than the prevalence of depression in the general population (39). This difference can be explained by several factors.

The linear relationship between a weakened immune system and increased susceptibility to depression, the relationship between chronic diseases and subsequent depression, and the association between HIV-related stigma, decreased social interaction, and resulting depression (40). By comparing the results obtained from this study, it can be concluded that the prevalence of HIV-related depression in Iran is higher than the statistics reported in other countries and also higher than the global statistics on depression among these patients. According to systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted in 2019 and 2024, the global prevalence of depression among HIV/AIDS patients was 31% and 34%, respectively, whereas in the Iranian population it was reported to be 56% (41, 42).

There are multiple reasons for the increased rate of depression in Iranian HIV patients compared to the global average. Key contributing factors include social disparities, insufficient self-awareness and education, economic difficulties, and the stigma associated with HIV (43, 44).

According to our study, men have a slightly higher rate of depression (58%) compared to women (52%). This higher rate in men may be attributed to the fact that the majority of patients included in the selected studies were male. Previous studies have shown varied perspectives on the gender distribution of depression among HIV/AIDS patients. According to a global assessment by Rezaei et al., men are believed to experience depression more than women (41). Similarly, a study in India found that depression prevalence was higher in men than in women (45), which differs from general population statistics showing 49% of women and 48% of men affected by depression (39).

However, in a study conducted in Africa, women with HIV/AIDS were found to suffer from depression more than men (46). This gender gap has been documented globally, not just in Africa. Researchers in China reported that women with HIV experience depression at a higher rate than men (47). According to studies conducted in India, women living with HIV experience both higher rates and more severe forms of depression than men (48, 49). The consistency of findings across multiple studies strengthens the evidence that women living with HIV are disproportionately affected by depression compared to men (50). This gender disparity in mental health disorders is notably pronounced in the context of HIV and AIDS (51).

Previous studies have demonstrated that younger patients exhibit a higher prevalence of depression compared to older adults with HIV, highlighting the role of social stigma and isolation in younger populations. Additionally, patients who did not adhere to their medication regimens exhibited higher levels of depression compared to those with good adherence (52). Individuals who had been on ART for less than 24 months and those with comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma were also found to have a greater occurrence of depression (53).

However, in the current study, we did not examine the prevalence of depression among HIV patients based on age group, ART status, adherence to ART, or the presence of other comorbidities.

5.3. Strength and Limitations

This is the first study to use a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the prevalence of depression among Iranians living with HIV/AIDS. The study examined depression rates in relation to various survey types, geographic regions, genders, and study quality.

However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis. First, all of the studies included were cross-sectional, which limits the ability to establish causal relationships. Additionally, many of the original studies did not specify whether the populations were from rural or urban areas, which presents another limitation. The generalizability of our findings may also be affected by the presence of heterogeneity across the studies. Lastly, another limitation is that outbreaks were not reported from all regions of Iran, which could have influenced the completeness of the analysis.

5.4. The Implication of the Findings

The significant number of Iranian HIV/AIDS patients experiencing depression highlights the need to integrate mental health services into HIV care programs. It is recommended that screenings for depression be routinely conducted, and healthcare providers should be prepared to offer appropriate interventions, such as counseling and psychiatric care. Reducing the stigma surrounding both HIV/AIDS and mental health will enhance treatment adherence and improve the overall quality of life for affected individuals.

Future longitudinal research should focus on how depression influences HIV treatment outcomes, including adherence to ART and disease progression. Evaluations for depression should be conducted using standardized instruments to minimize discrepancies in prevalence estimates. Additionally, engaging in qualitative research with HIV/AIDS patients who suffer from depression may offer further insights into the unique challenges and needs faced by this population. Implementing standard depression screening protocols is also recommended in HIV clinics.

5.5. Conclusions

In summary, our meta-analysis and comprehensive review highlighted the high prevalence of depression among Iranian individuals living with HIV/AIDS, with notable regional and gender-based variations. These findings emphasize the critical importance of integrating comprehensive mental health services into HIV care programs. Taking appropriate actions and implementing effective policies is essential to improve the quality of life for this vulnerable population.