1. Background

The advent of mobile technology has revolutionized the way individuals interact with the world, offering unprecedented access to information, communication tools, and resources at their fingertips. Smartphones, in particular, have become ubiquitous in modern society, serving as indispensable companions for personal, academic, and professional purposes (1). However, this growing dependence on mobile devices has given rise to a phenomenon known as "nomophobia," an abbreviation for "no mobile phone phobia." Nomophobia is characterized by feelings of anxiety, discomfort, or distress when individuals are unable to use their mobile phones or are separated from them (2). This condition has garnered significant attention in psychological and behavioral research due to its potential impact on mental health, social interactions, and occupational performance (3).

Among the populations most affected by nomophobia are nursing students, who rely heavily on mobile devices for academic purposes, clinical training, and communication with peers and mentors. While smartphones can enhance learning and provide instant access to medical resources, excessive dependence on these devices may hinder clinical performance (4). Nursing students are required to demonstrate critical thinking, effective communication, and hands-on skills in high-pressure healthcare environments. The presence of nomophobia could potentially impair their ability to focus, make sound decisions, and engage fully in patient care, thereby compromising the quality of healthcare delivery (5).

Nomophobia is not merely a psychological inconvenience; it has tangible implications for daily functioning and performance. For instance, studies have shown that individuals experiencing nomophobia often exhibit heightened levels of stress, reduced productivity, and impaired cognitive abilities (6). In the context of nursing education, where students are expected to balance theoretical knowledge with practical application, the adverse effects of nomophobia could be particularly pronounced. Nursing students must navigate complex clinical scenarios, communicate effectively with patients and healthcare teams, and maintain a high level of situational awareness — all of which require undivided attention and emotional stability (7). Excessive reliance on smartphones, coupled with the anxiety associated with being without them, could detract from these essential competencies (8).

Previous research has highlighted the prevalence of nomophobia among healthcare students, with some studies suggesting that it correlates with reduced academic productivity and heightened stress levels (7). For example, a study developed a self-reported questionnaire to explore the dimensions of nomophobia and found that a significant proportion of university students exhibited symptoms of this condition (8). Similarly, another study identified nomophobia as a potential exacerbating factor for individuals with pre-existing anxiety disorders, emphasizing the need for greater awareness and intervention strategies (9). Despite these findings, there remains a paucity of research examining how nomophobia specifically influences the clinical competencies of nursing students.

The relationship between nomophobia and clinical performance is particularly relevant in light of the increasing integration of technology into healthcare education. While smartphones and other digital tools have undoubtedly enhanced learning opportunities, they also pose unique challenges. For instance, excessive smartphone use during clinical rotations may lead to distractions, reduced engagement with patients, and diminished opportunities for hands-on practice (10). Furthermore, the constant connectivity afforded by mobile devices may blur the boundaries between work and personal life, contributing to burnout and emotional exhaustion among nursing students (11). These factors underscore the importance of understanding how nomophobia manifests in clinical settings and its potential consequences for patient care.

Despite the growing body of literature on nomophobia, several critical gaps remain unaddressed. First, while previous studies have explored the prevalence and psychological correlates of nomophobia among university students (12, 13), few have focused specifically on nursing students — a population uniquely positioned at the intersection of academic rigor and clinical practice (4). Second, existing research has predominantly examined nomophobia in relation to academic performance, with limited attention paid to its impact on clinical skills and patient outcomes (14). Addressing these gaps is essential for developing evidence-based strategies to support nursing students in managing their reliance on mobile devices while optimizing their clinical competencies. This gap is particularly concerning given the high-stakes nature of clinical practice, where lapses in attention or decision-making can have serious consequences for patient safety and care quality.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to address this research gap by investigating the relationship between nomophobia and clinical performance among nursing students.

Methods

3. Methods

3.1. Study Setting and Design

This cross-sectional study was carried out to analyze the relationship between the degree of nomophobia and the distraction associated with the use of smartphones by nursing students during their clinical performance. In this study, after obtaining approval from the Research Council and receiving ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee (code: IR.KAUMS.REC.1403.020), the researchers identified nursing students from Islamic Azad University of Kashan and Kashan University of Medical Sciences from September 2024 to January 2025 based on the inclusion criteria. A convenience sampling method was used to recruit participants for this study. Before completing the questionnaires, comprehensive information about the study’s purpose and the use of participants' data was provided, and their informed consent was obtained. All information was kept confidential and anonymous and was used only for research purposes.

3.2. Participants

The study included Bachelor's degree nursing students studying at Islamic Azad University of Kashan and Kashan University of Medical Sciences, aged 19 to 27. Inclusion criteria included undergraduate nursing students from Kashan, active mobile phone users (minimum of a few hours daily), and a signed informed consent form required for participation. Participants who failed to complete both the Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) and the Clinical Performance Questionnaire during the data collection period were excluded, as incomplete responses could compromise the integrity of the study results. Participants who experienced significant academic or clinical disruptions, such as failing a clinical rotation or withdrawing from a course during the study, were also excluded, as these events could independently affect clinical performance scores. To determine the appropriate sample size, this study utilized the Krejcie and Morgan (15), which recommended a sample of 200 participants based on the total population size.

3.3. Data Collection Tools

3.3.1. Baseline Data

The demographic variables included gender (male or female), age at diagnosis (in years), college term, academic average, smartphone ownership (in years), number of times checking the smartphone in a day, duration of checking the smartphone (hours), and phone placement in the classroom. The variables of this study were nomophobia and clinical performance.

3.3.2. Nomophobia Questionnaire

The research instrument used was the NMP-Q. The NMP-Q was created by Yildirim (16). This instrument consists of 20 closed-question items, which are favorable with a Likert scale. The items related to nomophobia were organized into seven ranges on a Likert scale: Absolutely inappropriate, inappropriate, slightly inappropriate, neutral, slightly appropriate, appropriate, and absolutely appropriate. The scoring interpretation for this questionnaire is as follows: A score of 20 indicates "no nomophobia," a score between 21 and 59 signifies "mild nomophobia," a score ranging from 60 to 99 denotes "moderate nomophobia," and a score between 100 and 140 reflects "severe nomophobia." Higher scores on this questionnaire indicate a higher level of nomophobia in students. The Persian version of the NMP-Q was translated and validated in Iran, demonstrating robust psychometric properties with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92, concurrent validity of 0.51, and test-retest reliability of 0.81 (17). In this study, the reliability of the Persian version was assessed, yielding a Cronbach's alpha of 0.90, indicating high internal consistency for the instrument among the study’s sample of nursing students.

3.3.3. Clinical Performance Questionnaire

The Clinical Performance Questionnaire for nursing students consists of 37 questions aimed at measuring the self-efficacy of nursing students' clinical performance. It was designed by Cheraghi et al. in 2009 (18). The scoring of this questionnaire is based on a 5-point Likert scale, where responses are assigned as follows: "Strongly Disagree" receives a score of 0 to 20, "Disagree" receives 30 to 40, "Neutral" receives 50 to 60, "Somewhat Agree" receives 70 to 80, and "Agree" receives 90 to 100. The minimum score is 37, and the maximum score is 185. A higher score indicates greater self-efficacy in clinical performance. The reliability of this questionnaire was reported as 0.96 for the entire questionnaire using the Cronbach's alpha method in Iran (19). In this study, the reliability of the Persian version was assessed for the study’s sample of nursing students, yielding a Cronbach's alpha of 0.94, confirming strong internal consistency.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with ethical approval obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.KAUMS.REC.1403.020) prior to data collection. All participants provided written informed consent after receiving comprehensive information about the study’s purpose, procedures, and data usage. Participation was voluntary, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. All data were kept confidential and anonymized, used solely for research purposes, and stored securely in compliance with ethical standards. No personal identifiers were collected, and participants faced no risks or direct benefits from involvement, ensuring their autonomy and privacy were protected throughout the study.

3.5. Data Collection Process

Data were collected from September 2024 to January 2025 using self-administered pencil-and-paper questionnaires, specifically the NMP-Q and the Clinical Performance Questionnaire, distributed to 200 undergraduate nursing students at Islamic Azad University of Kashan and Kashan University of Medical Sciences. Trained research team members administered the questionnaires in classroom settings during scheduled academic sessions to ensure a controlled and distraction-free environment. Participants were provided with clear instructions and completed the questionnaires anonymously after giving written informed consent, with all responses kept confidential and used solely for research purposes. The convenience sampling method was employed, and research team members collected the completed questionnaires immediately after each session to ensure data integrity and minimize missing responses.

3.6. Statistical Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using International Business Machines (IBM) SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) at an alpha = 0.05 significance level. Frequency and percentage were assessed to display descriptive information for the demographic characteristics. The data were found to be normally distributed according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In this study, a general linear model (GLM) was employed to investigate the relationship between the dependent variable, clinical performance, and the main independent variable, nomophobia. Both univariate and multivariate GLM analyses were conducted to assess the impact of nomophobia on clinical performance while controlling for various demographic variables. This methodological approach enabled a comprehensive understanding of how nomophobia and demographic factors collectively influence clinical performance outcomes.

4. Results

In this investigation involving 200 students, an analysis to investigate the relationship of nomophobia with the clinical performance of nursing students in 2024 was conducted. Regarding age distribution, the majority of students (141 individuals, 70.5%) were between 19 and 21 years old, followed by 52 students (26.0%) in the 22 - 24 age group, and 7 students (3.5%) aged 25 - 27 years. In terms of gender, 125 students (62.5%) were female, while 75 students (37.5%) were male. Students were also classified based on their academic term, with 98 students (49.0%) enrolled in terms 2 - 4 and 102 students (51.0%) in terms 5 - 8. Furthermore, the academic performance of the students was assessed based on their average scores. A total of 103 students (51.5%) had an academic average between 17 and 20, while 61 students (30.5%) had an average between 13 and 16.

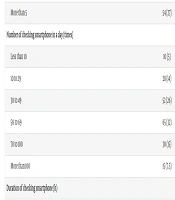

In this study, smartphone usage patterns among the students were examined, including smartphone ownership duration and frequency of smartphone checking per day. The majority of students (83, 41.5%) had owned their smartphones for 2 - 5 years, followed by 54 (27.0%) with more than 5 years of ownership. Additionally, 34 (17.0%) had their devices for 2 - 3 years, while fewer students owned them for 1 - 2 years (15, 7.5%) or less than a year (14, 7.0%). Most students checked their smartphones 50 - 69 times daily (65, 32%), followed by 30 - 49 times (52, 26.0%) and 70 - 100 times (30, 15.0%). Fewer checked them 10 - 29 times (28, 14.0%), less than 10 times (10, 5.0%), or more than 100 times (15, 7.5%). Regarding smartphone usage duration, most students (66, 33.0%) used their smartphones for 3 - 4 hours daily, followed by more than 4 hours (57, 28.5%) and 2 - 3 hours (37, 18.5%). Fewer students reported using their phones for 1 - 2 hours (21, 10.5%) or less than 1 hour (19, 9.5%). In terms of phone placement in the classroom, nearly half of the students (97, 48.5%) kept their phones on their desks, while 50 (25.0%) stored them in their bags. Others kept them in their pockets (14, 7.0%) or elsewhere (39, 19.5%) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| 19 - 21 | 141 (70.5) |

| 22 - 24 | 52 (26) |

| 25 - 27 | 7 (3.5) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 75 (37.5) |

| Female | 125 (62.5) |

| Term | |

| 2 - 4 | 98 (49) |

| 5 - 8 | 102 (51) |

| Academic average | |

| 13 - 16 | 61 (30.5) |

| 17 - 20 | 103 (51.5) |

| Smartphone ownership (y) | |

| Less than 1 | 14 (7) |

| 1 - 2 | 15 (7.5) |

| 2 - 3 | 34 (17) |

| 2 - 5 | 83 (41.5) |

| More than 5 | 54 (27) |

| Number of checking smartphone in a day (times) | |

| Less than 10 | 10 (5) |

| 10 to 29 | 28 (14) |

| 30 to 49 | 52 (26) |

| 50 to 69 | 65 (32) |

| 70 to 100 | 30 (15) |

| More than 100 | 15 (7.5) |

| Duration of checking smartphone (h) | |

| Less than 1 | 19 (9.5) |

| 1 to 2 | 21 (10.5) |

| 2 to 3 | 37 (18.5) |

| 3 to 4 | 66 (33) |

| More than 4 | 57 (28.5) |

| Phone placement in the classroom | |

| Desk | 97 (48.5) |

| Bag | 50 (25) |

| 14 (7) | |

| Other | 39 (19.5) |

Table 2 illustrated the level of nomophobia among the included nursing students in 2024. It showed that 12 respondents (6%) were in the category of no nomophobia, 55 respondents (27.4%) had mild nomophobia, 128 respondents (63.7%) were in the category of moderate nomophobia, and 5 respondents (2.5%) were in the category of severe nomophobia. This indicated that most respondents had moderate levels of nomophobia.

| NMP-Q Scores | Level | No. (%); N = 200 |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | No nomophobia | 22 (11) |

| > 20 to < 60 | Mild nomophobia | 58 (29) |

| 60 to < 100 | Moderate nomophobia | 112 (56) |

| ≥ 100 | Severe nomophobia | 8 (4) |

Abbreviation: NMP-Q, Nomophobia Questionnaire.

According to Table 3, nursing students with no nomophobia had a mean clinical performance score 22.989 units higher than those at the severe level, with marginal significance (P = 0.050). Individuals at the mild level showed a mean score 38.194 units higher than those at the severe level, which was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Additionally, individuals at the moderate nomophobia level had a mean clinical performance score 21.98 units higher than those at the severe level, which was statistically significant [B = 21.98, P = 0.03, 95% CI (17.23, 59.15)]. The mean clinical performance score for males was 10.09 units lower than for females, and this difference was statistically significant [B = -10.09, P = 0.01, 95% CI (-18.45, -1.72)]. The mean clinical performance score for students who had owned a smartphone for 2 to 3 years was 14.20 units lower than for those who had owned a smartphone for more than 5 years, with this difference also being statistically significant (P = 0.02). Furthermore, the mean clinical performance score for students who checked their phones 10 to 29 times a day was 21.25 units higher than for those in the reference category, with this difference being statistically significant (P = 0.02).

| Variables | B | P-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nomophobia | |||

| No | 22.98 | 0.05 a | (57.73, 97.02) |

| Mild | 38.18 | < 0.001 | (0.04, 45.92) |

| Moderate | 21.98 | 0.03 a | (17.23, 59.15) |

| Severe | Ref | Ref | - |

| Gender | |||

| Male | -10.09 | 0.01 a | (-18.45, -1.72) |

| Female | Ref | Ref | - |

| Term | |||

| 2 - 4 | 7.03 | 0.09 | (-1.12, 15.18) |

| 5 - 8 | Ref | Ref | - |

| Age (y) | |||

| 19 - 21 | 1.57 | 0.89 | (-20.92, 24.07) |

| 22 - 24 | -2.79 | 0.81 | (-26.19, 20.59) |

| 25 - 27 | Ref | Ref | - |

| Academic average | |||

| 13 - 16 | 6.60 | 0.12 | (-1.80, 15.01) |

| 17 - 20 | Ref | Ref | - |

| Smartphone ownership (y) | |||

| Less than 1 | 5.98 | 0.49 | (-11.16, 23.13) |

| 1 - 2 | 5.82 | 0.49 | (-10.87, 22.51) |

| 2 - 3 | -14.20 | 0.02 a | (-26.73, -1.68) |

| 2 - 5 | -6.37 | 0.21 | (-16.37, 3.62) |

| More than 5 | Ref | Ref | - |

| Number of checking smartphone in a day (times) | |||

| Less than 10 | 5.43 | 0.64 | (-17.64, 28.50) |

| 10 to 29 | 21.25 | 0.02 a | (3.17, 39.33) |

| 30 to 49 | -2.33 | 0.78 | (-18.90, 14.22) |

| 50 to 69 | 3.39 | 0.68 | (-12.79,19.58) |

| 70 to 100 | -3.80 | 0.67 | (-21.67, 14.07) |

| More than 100 | Ref | Ref | - |

| Duration of checking smartphone (h) | |||

| Less than 1 | 5.43 | 0.64 | (-17.64, 28.50) |

| 1 to 2 | 21.25 | 0.02 a | (3.17, 39.33) |

| 2 to 3 | -2.33 | 0.78 | (-18.90, 14.22) |

| 3 to 4 | 3.39 | 0.68 | (-12.79, 19.58) |

| More than 4 | Ref | Ref | - |

| Phone placement in the classroom | |||

| Desk | 6.06 | 0.27 | (-4.92, 17.05) |

| Bag | 3.45 | 0.58 | (-8.92, 15.84) |

| Ref | Ref | - | |

| Other | 13.89 | 0.13 | (-4.16, 31.96) |

Abbreviation: CI, credibility interval.

a P < 0.05

According to Table 4, the results of the multivariable GLM analysis revealed a significant difference in clinical performance scores based on nomophobia levels, with only significant P-values reported. Participants with mild nomophobia had clinical performance scores that were 34.24 units higher compared to those with severe nomophobia (P = 0.002). No other significant differences were observed. Additionally, the analysis indicated a significant association between the frequency of smartphone checking and clinical performance scores. Participants who checked their smartphones 10 to 29 times per day had clinical performance scores that were 22.19 units higher compared to those who checked their smartphones more than 100 times per day [P = 0.01, 95% CI (5.05, 39.32)], indicating a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). No other significant differences were observed.

| Variables | B | P-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nomophobia | |||

| No | 15.59 | 0.18 | (-7.28, 38.47) |

| Mild | 34.24 | 0.002 a | (12.99, 55.49) |

| Moderate | 18.29 | 0.08 | (-2.18, 38.77) |

| Severe | Ref | Ref | - |

| Gender | |||

| Male | -7.40 | 0.07 | (-15.60, 0.80) |

| Female | Ref | Ref | - |

| Term | |||

| 2 - 4 | 4.34 | 0.27 | (-3.54, 13.82) |

| 5 - 8 | Ref | Ref | - |

| Smartphone ownership (y) | |||

| Less than 1 | 5.02 | 0.55 | (-11.78, 21.83) |

| 1 - 2 | 4.46 | 0.58 | (-11.51, 20.45) |

| 2 - 3 | -14.47 | 0.20 | (-26.68, -2.26) |

| 2 - 5 | -7.02 | 0.16 | (-16.90, 2.86) |

| More than 5 | Ref | Ref | - |

| Number of checking smartphone in a day (times) | |||

| Less than 10 | 4.95 | 0.65 | (-17.14, 27.04) |

| 10 to 29 | 22.19 | 0.01 a | (5.05, 39.32) |

| 30 to 49 | 2.84 | 0.72 | (-13.13, 18.82) |

| 50 to 69 | 10.85 | 0.17 | (-4.71, 26.41) |

| 70 to 100 | 6.19 | 0.46 | (-11.14, 23.53) |

| More than 100 | Ref | Ref | - |

| Duration of checking smartphone (h) | |||

| Less than 1 | -0.77 | 0.91 | (-15.36, 13.82) |

| 1 to 2 | 11.87 | 0.10 | (-2.31, 26.06) |

| 2 to 3 | 7.06 | 0.24 | (-4.83, 18.96) |

| 3 to 4 | 0.11 | 0.98 | (-10.28, 10.52) |

| More than 4 | Ref | Ref | - |

Abbreviation: CI, credibility interval.

a P < 0.05

5. Discussion

The findings of this study provide critical insights into the relationship between nomophobia and clinical performance among nursing students, offering a deeper understanding of how smartphone dependency influences their ability to deliver high-quality patient care. The results align with existing literature in some aspects while diverging in others, highlighting both consistencies and gaps in the current body of knowledge. By interpreting these findings in light of prior research, we can better understand the implications for nursing education and practice.

This study found that most nursing students exhibited moderate levels of nomophobia, with only a small proportion experiencing severe symptoms. These results are consistent with earlier studies that have documented moderate nomophobia as the most common level among university students (20). For instance, one study reported that a significant percentage of students experienced moderate nomophobia, characterized by feelings of discomfort when separated from their smartphones but not debilitating anxiety (21). Similarly, another investigation noted that medical students often fall into the moderate category, suggesting that this level of dependency is widespread among young adults who rely heavily on mobile devices for academic and personal purposes (22).

However, the relatively low prevalence of severe nomophobia observed in this study contrasts with findings from other populations. For example, one study identified higher rates of severe nomophobia among adolescents, particularly those in urban settings where smartphone use is pervasive (23). This discrepancy may reflect differences in age, cultural contexts, or institutional policies regarding smartphone usage. In nursing education, where students are trained to prioritize patient care over personal distractions, the lower prevalence of severe nomophobia could indicate a degree of self-regulation or institutional guidance in managing smartphone dependency.

The results suggest that nursing students with mild nomophobia tend to perform better clinically compared to those with severe nomophobia. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that excessive smartphone use can impair cognitive functioning, decision-making, and situational awareness — skills that are essential for effective clinical practice (24). For instance, one study found that nursing students who reported higher levels of smartphone addiction demonstrated reduced engagement during clinical rotations and struggled to maintain focus on patient care tasks (25). Similarly, another investigation highlighted the role of digital distractions in compromising patient safety, emphasizing the need for strategies to mitigate smartphone-related interruptions in healthcare settings (26).

Interestingly, participants with no nomophobia did not show a marked improvement in clinical performance compared to those with mild or moderate levels. This outcome diverges from some earlier studies that have suggested complete detachment from smartphones might enhance focus and productivity (27). However, it also underscores the dual nature of smartphone use: While excessive reliance can hinder performance, moderate use provides access to valuable educational resources and communication tools that support learning and patient care. This nuanced relationship highlights the importance of striking a balance between leveraging the benefits of smartphones and minimizing their potential drawbacks.

The study revealed that female nursing students tended to outperform their male counterparts in clinical settings. This finding is consistent with prior research suggesting that female students often excel in areas requiring empathy, communication, and attention to detail — qualities that are crucial for nursing practice. For example, one study noted that female nurses typically demonstrate stronger interpersonal skills and emotional intelligence, which contribute to better patient outcomes (28). However, it is important to interpret these results cautiously, as gender differences in clinical performance may be influenced by a variety of factors beyond nomophobia, including personality traits, coping mechanisms, and institutional support systems.

Participants who had owned smartphones for longer periods appeared to perform better clinically than those with shorter ownership durations. This finding suggests that prolonged exposure to smartphones may enable individuals to develop better strategies for managing device usage, thereby reducing its negative impact on clinical performance. Prior studies have similarly highlighted the role of experience in shaping digital behaviors; for instance, one investigation found that students with greater familiarity with mobile technology were less likely to exhibit signs of nomophobia and more likely to use their devices responsibly (29). These results underscore the potential benefits of integrating smartphone management training into nursing curricula to help students navigate the challenges associated with digital technology.

The study found that nursing students who checked their smartphones less frequently performed better clinically than those who engaged in frequent checking. This result aligns with existing literature linking excessive smartphone use to reduced attention spans, impaired memory retention, and heightened stress levels (27). For example, one study demonstrated that frequent smartphone interruptions disrupted workflow and diminished productivity among healthcare professionals (30). Conversely, moderate smartphone use appears to strike a balance between staying connected and maintaining focus, enabling students to perform optimally in clinical rotations. These findings highlight the importance of fostering mindful smartphone habits, such as limiting unnecessary checks and establishing designated "phone-free" periods during clinical tasks.

The findings of this study resonate with several key themes in the existing literature on nomophobia and clinical performance. For example, the association between moderate nomophobia and improved clinical performance mirrors the findings of one study, which emphasized the dual role of smartphones as both tools and distractions (31). Similarly, the negative impact of frequent smartphone checking aligns with observations about digital distractions in healthcare environments (32).

However, some aspects of this study diverge from prior research. For instance, the lack of a clear advantage for participants with no nomophobia contrasts with studies suggesting that complete detachment from smartphones enhances focus (33). This discrepancy may reflect the unique demands of nursing education, where access to digital resources is often essential for learning and patient care. Furthermore, the observed gender differences in clinical performance add nuance to earlier findings, highlighting the need for more comprehensive investigations into the intersection of gender, nomophobia, and clinical competencies.

Researchers should investigate how individual factors, such as personality traits, coping mechanisms, and emotional resilience, influence the relationship between nomophobia and clinical performance. For example, do students with higher levels of conscientiousness or better stress-management skills exhibit lower levels of nomophobia and perform better clinically? Understanding these dynamics could help tailor interventions to meet the unique needs of different student groups.

Future studies should examine how cultural norms, socioeconomic factors, and institutional policies shape the prevalence and impact of nomophobia. For example, do students in institutions with strict smartphone restrictions during clinical rotations perform better than those in environments with more lenient rules? Cross-cultural comparisons could also reveal how societal attitudes toward technology influence students' relationships with their devices and their ability to focus on patient care.

5.1. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant relationship between nomophobia and clinical performance among Iranian nursing students, demonstrating that severe nomophobia is associated with lower clinical performance, while mild and moderate nomophobia levels correlate with better outcomes. Additionally, moderate smartphone use, characterized by checking the phone 10–29 times per day, and is linked to improved clinical performance compared to excessive use. Female students exhibited higher clinical performance scores than males, and those with longer smartphone ownership (over 5 years) performed better than those with shorter durations. These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions to manage smartphone dependency, encouraging responsible use to enhance clinical competencies and ensure optimal patient care. By addressing these insights, nursing educators can develop strategies to support students in balancing digital technology use with professional responsibilities, ultimately improving clinical performance and patient safety in modern healthcare settings.

5.2. Limitations

While this study contributes valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences about the relationship between nomophobia and clinical performance, necessitating longitudinal studies to examine how these variables evolve over time. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of response bias, underscoring the need for objective measures such as smartphone usage logs or direct observations of clinical behavior. However, the study’s strengths include its robust sample size of 200 undergraduate nursing students, which enhances the reliability of the findings, and the use of validated Persian-language instruments with high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90 for NMP-Q and 0.94 for the Clinical Performance Questionnaire in this study). Furthermore, the application of both univariate and multivariable GLM analyses allowed for a comprehensive exploration of the relationship while controlling for demographic variables, and the focus on Iranian nursing students addresses a gap in the literature regarding nomophobia in this specific population.

5.3. Future Research

Future research should also explore additional variables, such as personality traits, coping mechanisms, and institutional policies regarding smartphone use, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing clinical performance. Expanding the scope of future studies to include diverse geographic regions, institutional settings, and demographic groups would strengthen the external validity of the findings and inform the development of targeted interventions.