1. Context

Dermal fillers are a mainstay of aesthetic medicine. Currently, the most common ingredient in fillers is hyaluronic acid (HA). However, there was an evolution of products that brought us to where we are today. This review aims to cover the data on soft tissue volumizers before the advent of collagen.

2. Discussion

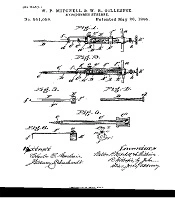

Soft tissue augmentation dates back to the 19th century, when Neuber (1) excised fat lobules from the arm for facial scar, and concluded that larger grafts were less predictable than smaller ones. Czerny (2) used fat from a lipoma to introduce for breast reconstruction in 1895. Lexer (3) studied fat survivability, and concluded that excised fat grafts should be handled with care in both excision and implantation in order to achieve good results. By 1890s, the hypodermic syringe was being developed in glass and silver (Figure 1) (4, 5).

Lexer (6) presented successful volumization of the face and breasts. By 1911, the hypodermic needle/syringe was use to inject particles of excised fat for post-rhinoplasty irregularities, with excellent results in the short term, and significant subsequent resorption (7). In 1912, the first photographic evidence of fat transplantation using a hypodermic needle/syringe for facial lipoatrophy was published (8). In 1923, the first histologic evidence of transplanted fat that had engrafted was published, and therefore, fat was not just a mass that would be converted to scar tissue, but a true live tissue transplantation (9). In 1926, the term cannula was introduced in the realm of fat transplantation, when Miller (10) presented his technique of face and neck scar correction with injection of fat through a cannula. In 1931, facial lipoatrophy was treated successfully with fat grafting (11). Next, breast reconstruction with fat grafting was reported in 1941, with one breast receiving a large fat graft and another receiving a combination fat/fascia graft, with the fat/fascia graft having better volume retention (12). In 1950, Peer predicted that his technique yielded a 50% survivability of fat grafts (13). He examined histologic samples of transplanted fat to develop the “cell survival theory,” concluding that fat viability was correlated to graft volume (14).

In 1951, Gray et al. (15) performed dermis/fat grafts, and reported complications, including cyst formation. In 1969, Sawhney et al. (16) reported animal studies of dermis/fat grafts done on pigs. Fat/dermis grafts measuring 1.5 × 1.5 cm were transplanted with dermis side down. At one week, the grafts had a reduction of volume by 6.7%; 2 weeks, a 9% reduction of volume; 3 weeks a 20% reduction of volume; 4 weeks, a 33.3% reduction of volume vis-a-vie the original transplant. All the fat was replaced with fibrous tissue, yet the volume was maintained in the 4-week study. Ben-Hur and Neuman (17) determined that epithelial cells were causing cysts and hence the cyst formations reported by Gray et al. were most likely due to inadequate de-epithelialization (18). The game changes came in 1975, when a father/son gynecologist team changed the way fat was harvested, and set in motion a technique that is ever more popular today (17). The Fischer (18) used a blunt metallic suction cannula and invented modern-day liposuction. This allowed procurement of abundant viable fat cells (19).

Concurrently, petroleum was discovered, from which came mineral oil. Refined mineral oil produced liquid paraffin. Gersuny (20) published the first medical use of paraffin with a hypodermic needle/syringe in 1900 for creation of a testicular prosthesis in a man who had a bilateral orchiectomy due to tuberculosis. From 1899 to 1914, paraffin was used for breast augmentation. The Derma Featural Company, incorporated in England, was focused on cosmetic surgery, and a court case in 1908 describes the use of hot paraffin injected into the nasal skin and molded to the desired shape. Derma Featural’s largest account was a dermatologist named John Humphrey Woodbury (Figure 2) in New York, NY, who had established cosmetic surgery centers in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, St. Louis, and Washington, DC. However, he got tied up with many law suits and committed suicide in 1909 (21). The most notable victim of paraffin injection was the beautiful Gladys Marie Spencer-Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough (Figure 3). She tried to even a small nasal tip asymmetry with paraffin and had some injected into her jaw. The procedure caused major deformities to the point that she became a recluse. She died at the age of 96 in 1977 (22). By 1912, complications of paraffin injection were reported, including, draining persistent fistulas, pulmonary embolism, ulceration, necrosis, breast amputation, and death (23, 24).

Paraffin complications opened the door to a new comer, “Cleopatra’s needle” (25), where liquid silicone was used for breast augmentation. Liquid silicone was developed and used during world war II as insulation for electrical transformers (26). This began in Japan, where stolen Army stocks of industrial silicone were being injected into the breasts of local prostitutes, creating a more Western appearing contour. Dr. James Brown applied silicone to soft tissue supplementation in 1947 (27). He further studied the safety and complications, concluding that silicone is biocompatible and a safe tissue enhancer (28). Dow Corning introduced a liquid silicone called MDX4-4011, which was FDA approved for coating syringes, but started being used in an unregulated manner for soft tissue augmentation. In 1964, Carol Doda became the face of silicone injections, as she flaunted her breasts in topless burlesques. (Figure 4). Some even mixed different oils, including olive oil and paraffin to the silicone oil to develop their individualized mixtures (29). However, many complications began being reported (30), including granulomas, product migration (31), granulomatous hepatitis, and death (32). In 1975, Nevada became the first state to outlaw the use of injectable silicones. Currently, only two liquid forms of silicone are FDA approved, and only for intra-ocular injection to treat retinal detachment (33). Many have used medical grade silicone off-label for soft-tissue augmentation and by using the droplet-technique. This technique induced fewer complications. However, the illegal use of non-medical grade liquid silicones in the hands of non-medical or ill trained individuals has skyrocketed and resulted in multiple deaths (34).

3. Conclusion

The hunt for the ideal filler was now hotter than ever, since a market had been developed, which demanded easy and affordable soft-tissue volumization. Collagen and a slew of other fillers followed, but the ideal filler is still quite elusive.