1. Introduction

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is a subset of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS). It is now recognized as one of the severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) with significant morbidity and mortality, chiefly because of derangement of renal or liver functions (1). Although its initial nosology, such as phenytoin hypersensitivity syndrome, can be attributed to its frequent linkage to this drug (2), it was later found to be caused by various other drugs. Anticonvulsants and sulfonamides are the most common offenders (2). The pathophysiology remains incompletely understood but involves the reactivation of viruses and activation of lymphocytes. It manifests more commonly as a maculopapular cutaneous rash with fever and lymphadenopathy. The severity and prognosis of this syndrome are dictated by the extent of internal organ involvement and dysfunction, which can result in poor outcomes. Early diagnosis and immediate cessation of the suspected offending drug are the keys to successful management. Patients with DRESS syndrome should be managed in an intensive care setup with appropriate supportive care and infection control.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Case 1

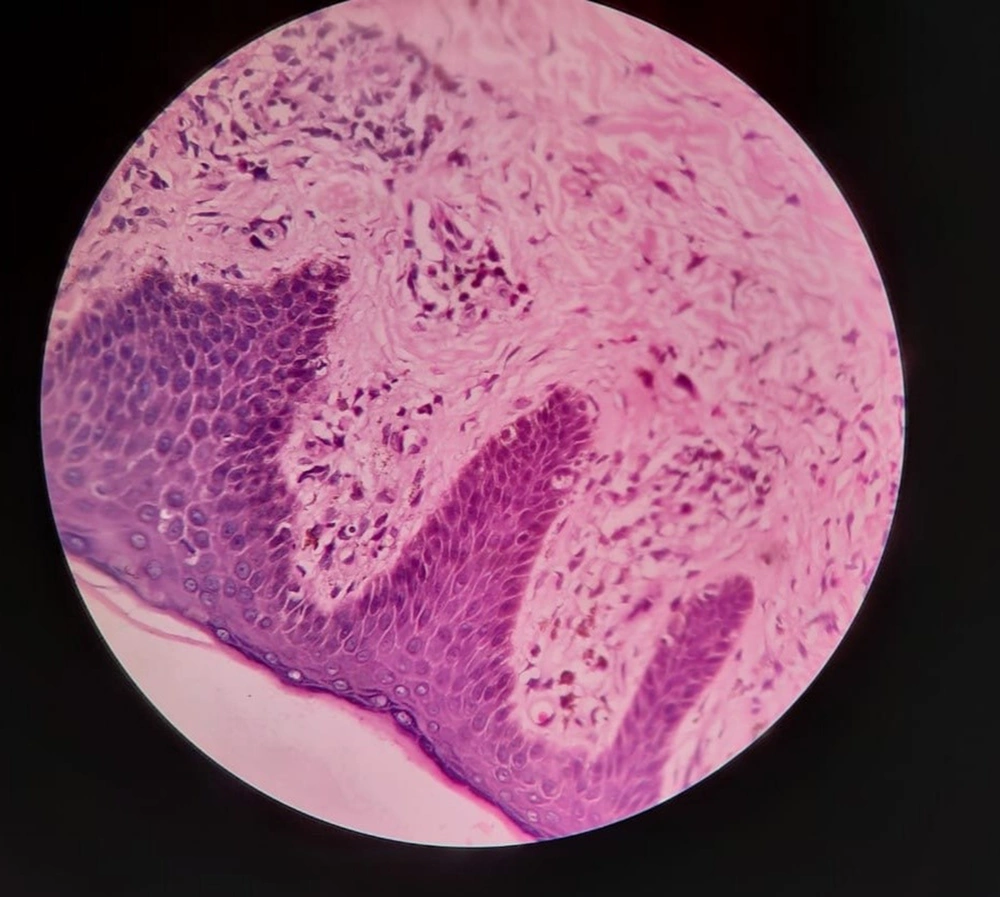

A 28-year-old male presented with a sudden onset generalized pruritic erythematous maculopapular rash involving the face, trunk, back, and limbs (Figure 1), associated with high-grade fever and malaise. He also had oral, ocular, and genital erosions and bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy. He had been taking Tab. Cefixime (200 mg twice a day) for 7 days for his upper respiratory tract infection. The rash had worsened despite discontinuation of cefixime, and he was admitted to our tertiary care center. Laboratory investigations revealed elevated levels of serum total bilirubin (6.27 mg/dL), aspartate transaminase (AST) (200 IU/L), and alanine transaminase (ALT) (170 IU/L), and also leukocytosis. Absolute eosinophil count was > 1000 cells/cm. Ultrasonography of the abdomen showed hepatomegaly, and the chest X-ray was unremarkable. RT-PCR test for COVID 19 was negative. Skin biopsy revealed perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and eosinophilic infiltration in the superficial dermis (Figure 2). As the clinical history and laboratory findings did not fulfill the requisite standard of the European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (RegiSCAR) criteria for DRESS syndrome, the J-SCAR scoring system was applied, and he was diagnosed with atypical DRESS syndrome. He was treated with a short rapidly tapered course of injectable dexamethasone (6 mg; prednisolone equivalent dose of 0.75 mg/kg/day) along with antibiotics (intravenous vancomycin injection (500 mg) every 12 hours for 5 days). The patient achieved complete resolution of rash after 7 days of treatment (Figure 3) with normalization of laboratory parameters within 21 days.

2.2. Case 2

A 32-year-old male had taken cefpodoxime tablet (200 mg; twice a day for 5 days) for a furuncle over his leg, consequent to which he developed diffuse erythematous to violaceous morbilliform rash (Figure 4). Laboratory investigation showed elevated levels of serum total bilirubin (4.2mg/dL), AST (325 IU/L), ALT (198 IU/L), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (210 IU/L). Hemogram showed leukocytosis and eosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count 1250 cells/cm). Ultrasound (abdomen and pelvis) also revealed hepatomegaly. Cefpodoxime was withheld immediately; however, he rapidly progressed to exfoliative dermatitis with oral, ocular, and genital erosions and bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy. A diagnosis of atypical DRESS syndrome was confirmed on the basis of J-SCAR criteria, and he was administered with intravenous dexamethasone (6mg; prednisolone equivalent dose of 0.75 mg/kg/day) with rapid tapering of dose over 10 days. Marked improvement was observed after one week with gradual resolution of all signs and symptoms and laboratory parameters.

3. Discussion

DRESS syndrome was a term coined by Bouquet in 1996 to denote a drug reaction manifesting as rash, fever, and systemic involvement (1-3). DRESS is rare, with the approximate incidence of 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 10,000 drug exposures (4). Mortality is high (10% - 20%), with hepatic failure reported as an ominous prognostic factor (4). Although the specific pathogenesis is obscure, the following conditions are mandatory for DRESS syndrome:

1- A genetic predisposition that modifies immune response.

2- An extrinsic trigger, mostly a viral infection.

3- Defect in drug metabolism leading to the accumulation of intermediates.

Drugs usually effective for the DRESS syndrome are antimicrobials, anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, antivirals, and antidepressants (5). Cephalosporins (particularly cefpodoxime) are infrequently responsible for this type of serious adverse cutaneous drug reaction (6). The presentation generally begins with fever, followed by the appearance of a rash accompanied by mucositis (usually oropharyngeal) and lymph node enlargement. Subsequently, systemic involvement may occur in the form of liver, hematologic, renal, and pulmonary dysfunction (7, 8). Skin manifestations (as seen in both our patients) chiefly comprise a maculopapular or morbilliform eruption, which progressively involves over 50% body surface area and includes two or more of the following conditions: facial edema, infiltrative lesions, scaling, and/or purpura. Irrespective of any intervention, DRESS syndrome follows a protracted clinical course (2 - 3 weeks after the onset), most likely due to the reactivation of several herpes viruses (8). Recent research has illustrated the sequential role of various herpes viruses; however, HHV-6 is the preliminary virus incriminated as a causative agent (9). The cascade of viral reactivation extending over a prolonged duration is initiated by Epstein Barr virus (EBV) or HHV-6, followed by human herpes virus-7 (HHV-7) reactivation and, eventually, the proliferation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) (9). However, in our resource-limited setting, tests to demonstrate reactivation of HHV-6 and HHV-7 could not be performed. Currently, there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome. In the absence of any international consensus, there are various criteria proposed by the study group of the European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reaction named as the RegiSCAR scoring system (Table 1) (10). Different definitions and nosology have been proposed by Bocquet et al. (cited in Choudhary et al.) (1) and Sontheimer and Houpt (cited in Ben M'rad et al.) (11) to elucidate the clinical and pathological characteristics of DRESS/DIHS, while the Japanese study group of severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs (J-SCAR) has endorsed certain other criteria (12). As eosinophilia is observed in only up to 60% - 70% of patients who satisfy the criteria (8, 11), it has been recommended that the term ‘drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) may be more appropriate instead of DRESS. In accordance with the J-SCAR scoring system, both our cases fulfilled 6 out of 7 criteria (maculopapular rash, fever, prolonged clinical symptoms after discontinuation of drug, liver abnormalities, leucocyte abnormalities, and lymphadenopathy) to support the diagnosis of cephalosporin-induced atypical DRESS syndrome (Box 1) (12). The striking feature observed was the unusual short temporal and spatial reaction to drug intake with manifestations developing within a week after the start of cephalosporin, in contrast to the specified latent period of 2 to 6 weeks (1, 2). DRESS/DIHS has a broad range of symptoms, including severe drug reactions, like acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, erythroderma, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis that should be distinguished on the basis of specific cutaneous findings and evidence of visceral involvement. Other dermatologic disorders that can simulate DRESS are various viral exanthems (retroviral disease, Hepatitis B, EBV, CMV, Kawasaki disease, etc.), autoimmune connective tissue disorders, serum sickness-like reactions, lymphoma, and pseudolymphoma.

| Items | Score | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Fever ≧ 38.5°C | N/U | Y | ||

| Enlarged lymph nodes | N/U | Y | > 1 cm and ≧ 2 different areas | |

| Eosinophilia ≧ 0.7 × 109/L or ≧ 10% if WBC < 4.0 × 109/L | N/U | Y | Score 2, when ≧ 1.5 × 109/L or ≧ 20% if WBC < 4.0 × 109/L | |

| Atypical lymphocytosis | N/U | Y | ||

| Skin rash | U | Rash suggesting DRESS: ≧ 2 symptoms: purpuric lesions (other than legs), infiltration, facial edema, psoriasiform desquamation | ||

| Extent > 50% of BSA | N/U | Y | ||

| Rash suggesting DRESS | N | U | Y | |

| Skin biopsy suggesting DRESS | N | Y/U | ||

| Organ involvement | N | Y | Score 1 for each organ involvement, maximal score: 2 | |

| Rash resolution ≧ 15 days | N/U | Y | ||

| Excluding other causes | N/U | Y | Score 1 if 3 tests of the following tests were performed and all were negative: HAV, HBV, HCV, mycoplasma, chlamydia, ANA, blood culture | |

Abbreviations: ANA, antinuclear antibody; BSA, body surface area; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; N, no; U, unknown; WBC, white blood cell; Y, yes.

aFinal score: < 2: No DRESS, 2-3: Possible DRESS, 4 - 5: Probable DRESS, > 5 Definite DRESS.

| Diagnostic Criteria for DRESS |

|---|

| A maculopapular rash developing > 3 weeks after drug initiation |

| Clinical symptoms continuing > 2 weeks after stopping therapy |

| Fever > 38°C |

| Liver abnormalities (ALT > 100 IU/L) or other organ involvement |

| Haematological abnormalities |

| Leucocytosis (> 11 × 109/L) |

| Atypical lymphocytes (> 5%) |

| Eosinophilia (> 1.5 × 109/L) |

| Lymphadenopathy |

| HHV-6 reactivation |

| Total score |

| 7 = Typical DRESS |

| 5 = Atypical DRESS |

| < 5 = Consider other diagnosis |

3.1. Conclusions

Atypical DIHS is a concept that can be applied for patients with early-onset, albeit typical clinical presentations, or those, for whom HHV-6 reactivation cannot be found. A significant proportion of cases might not necessarily meet all the requisite criteria simultaneously, especially at the onset. This highlights the importance of meticulous clinical and laboratory monitoring throughout the course of the episode. In such situations, J-SCAR scoring is a useful diagnostic tool. More importantly, a keen search to determine the probable causative drug is essential to do not miss rare culprits, like cephalosporins.