1. Background

Herpes zoster (HZ) or shingles is a viral disease caused by the endogenous reactivation of an infection by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Following the primary infection of varicella, the virus persists asymptomatically in the sensory cranial nerve ganglions and spinal dorsal root ganglia. As cellular immunity to the VZV decreases with age or due to immunosuppression, the virus reactivates and travels along sensory nerves to the skin, causing the distinctive prodromal pain followed by the eruption of the papulovesicular rash. Clinically, the disease is characterized by the eruption of grouped vesicles on erythematous bases or erythematous papules distributed in a particular dermatolme (1). As the age increases, the incidence of shingles increases, particularly after 50 years of age. Moreover, shingles is more frequently observed in immunocompromised patients and children with a history of intrauterine varicella or varicella occurring within the first year of life; the latter has increased the risk of developing shingles at an earlier age (2).

The mainstay of the prevention of HZ infection is vaccination against the HZ virus (3). There are a great number of treatment modalities available for HZ infection and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). Nonetheless, approximately 22% of patients with HZ still suffer from PHN (4). The wider adoption of varicella vaccination results in the decreased prevalence of varicella, thereby leading to decreased chances of periodic re-exposure to varicella. This, in turn, makes it possible to decrease the natural boosting of immunity and result in an increased incidence of HZ (5). Although HZ is a common condition without any serious consequences, its incidence and pattern of occurrence in the era of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, use of newer immunosuppressive agents, and associated systemic conditions require constant relook. This study was carried out to investigate the clinico-epidemiological profile of this disease in a busy tertiary care setup where dermatology load is high with numerous cross-referrals from other specialties.

2. Objectives

To study the clinical and epidemiological profile of cases of HZ in a tertiary care centre with an emphasis on precipitating factors, immunocompromised status, and association with HIV infection or any systemic disease; to determine the incidence of PHN and disease burden in a tertiary care centre.

3. Methods

This prospective study was conducted in a tertiary care centre of North India within January-June 2019. All consecutive cases of HZ attending dermatology outpatient department (OPD) and referred from other departments were enrolled in the study after obtaining informed consent. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the hospital. The diagnosis of HZ was clinical. Whenever doubt existed, Tzanck smear was prepared to confirm the diagnosis. The patients who were less than 10 years of age or unwilling for follow-up were excluded from the study. All patients were followed up for at least 3 months to a maximum of 6 months since HZ diagnosis.

The data were collected as per predesigned proforma and included age, gender, duration of HZ, precipitating factors, a history recurrence, and family history. A detailed clinical examination was carried out. Furthermore, the clinical data, including morphology, involvement segment, duration between neuralgia, vesicular eruptions, and complications, if any, were recorded. Laboratory investigations, including complete blood count, blood sugar, renal function test, and urine analysis, were carried out. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for HIV antibody was performed in all cases.

All patients were treated with acyclovir if reported with supportive therapies within 72 hours of onset. Follow-up was planned fortnightly for 1 month and monthly for the next 5 months. During the follow-up course of the disease, resolution time and complications, including PHN, were assessed. The opinions of other specialties, such as ophthalmology and general medicine, were sought whenever necessary. The detailed data were endorsed in an Excel sheet for analysis. Mean, average, percentage, and standard deviation were calculated based on the collected data using Microsoft Excel for Windows 10 operating system.

4. Results

Overall, 203 cases of HZ were reported to the dermatology OPD within January - June 2019. Moreover, 13 patients could not report for follow-up and were excluded from the study. A total of 190 consecutive cases were included in the present study, 126 and 64 of whom were male and female, respectively (a male to female ratio of 2: 1). This ratio constituted 0.84% of the total dermatology OPD cases for the aforementioned duration. The age group of patients included in the study was within the range of 10 - 90 years (mean age: 43.2 ± 12.4 years). Of the 190 patients, 101 subjects (53%) were below 50 years of age; however, the remaining 89 subjects (47%) were above 50 years of age. Additionally, 14 cases (7.3%) were below 20 years of age. Table 1 shows the age and gender distribution in this study.

| Age Groups (y) | Male | Female | Total Cases; No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 - 20 | 8 | 6 | 14 (7.3) |

| 21 - 30 | 11 | 7 | 18 (9.4) |

| 31 - 40 | 20 | 12 | 32 (16.8) |

| 41 - 50 | 24 | 13 | 37 (19.4) |

| 51 - 60 | 27 | 15 | 42 (22.1) |

| 61 - 70 | 21 | 7 | 28 (14.7) |

| 71 - 80 | 16 | 4 | 18 (9.4) |

| 81 - 90 | 01 | - | 1 (0.5) |

The mean age values of male and female patients were 50.3 ± 12.3 and 48.2 ± 10.2 years, respectively. The majority (n = 120; 63%) of cases were observed in summer within April-June. Out of the 190 cases, 112 cases (59%) had a definite history of chickenpox during childhood. The remaining 78 cases (41%) either had no history of chickenpox at all or did not remember it.

A total of 66 patients (34%) had comorbidities in the form of diabetes mellitus (thirty five), hypertension (twenty eight), carcinomas (nine), coronary artery disease (eight), chronic kidney disease (two), skin diseases (six), pulmonary tuberculosis (two), rheumatoid arthritis (one), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (one), ankylosing spondylitis (one), and squamous cell carcinoma (one). Additionally, 18 patients (9%) recently had precipitating factors in the form of extreme physical exertion, a history of fever, and surgery. In this study, 43 patients (22%) had some form of immune suppression in the form of diabetes mellitus and steroid or immunosuppressive intake. Moreover, 11 patients had HIV infection, inclusive of 8 male and 3 female subjects. Two patients were diagnosed with HIV while screening. Recurrence was observed in four cases (2.1%), and family history was present in five cases (2.6%).

In this study, 11 cases (5.7%) had significant constitutional symptoms, including high-grade fever, headaches, body ache, and joint pains as a prodrome or concurrently with eruption. Five cases had a sore throat with a dry cough. Persistent hiccup as an uncommon complaint in HZ was observed in one patient in whom thoracic dermatome involvement was present. Table 2 shows the segment-wise distribution. Thoracic dermatome was most commonly affected (n = 90; 47.3%) followed by the trigeminal nerve (n = 28; 14.7%). A total of 17 patients (8.9%) had herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), 4 of whom had corneal involvement. Three subjects had multidermatomal involvement, two of whom were HIV positive. Furthermore, 98 patients had right-sided lesions; nonetheless, 92 patients presented with the involvement of the left side. Segmental neuralgia during the course of the disease was observed in more than 90% of patients in the form of pricking, burning, shooting, deep boring pain, and interfering with sleep in a few cases. The pain was more evident in old age than in the other age group. The vesicular eruption was preceded by pain in 169 cases (90%). Eruptions were noticed within 2 days of pain in 70% of patients. They followed the classical progression of erythematous papule or macule, vesiculation (1 - 2 days), pustulation (1 - 7 days), and crusting over 10 - 15 days.

| Region | Gender | Side | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Right | Left | ||

| Cranial | 24 | 04 | 16 | 12 | 28 (14.7) |

| Cervical | 8 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 18 (9.4) |

| Thoracic | 56 | 34 | 48 | 42 | 90 (47.3) |

| Lumbar | 12 | 07 | 10 | 9 | 19 (10) |

| Sacral | 05 | 03 | 5 | 3 | 08 (4.2) |

| Cervicothoracic | 03 | 01 | 2 | 2 | 04 (2.1) |

| Thoracolumbar | 03 | 02 | 3 | 2 | 05 (2.6) |

| Lumbosacral | 05 | 01 | 4 | 2 | 06 (3.1) |

| Multidermatomal | 02 | 01 | 2 | 1 | 03 (1.5) |

The resolution period was within the range of 8 - 15 days. In immunocompromised individuals, it was prolonged and lasted up to 20 days. A total of 21 patients (11%) required hospitalization. The duration of hospitalization varied within 7 - 16 days, with an average of 9 days. Additionally, 51 (27%) out of the total of 190 patients developed complications, including secondary bacterial infection (n = 12), severe ulceration (n = 3), keloid (n = 2), scarring (n = 2), motor weakness (n = 1), trigeminal neuralgia (n = 1), and eye involvement (n = 4).

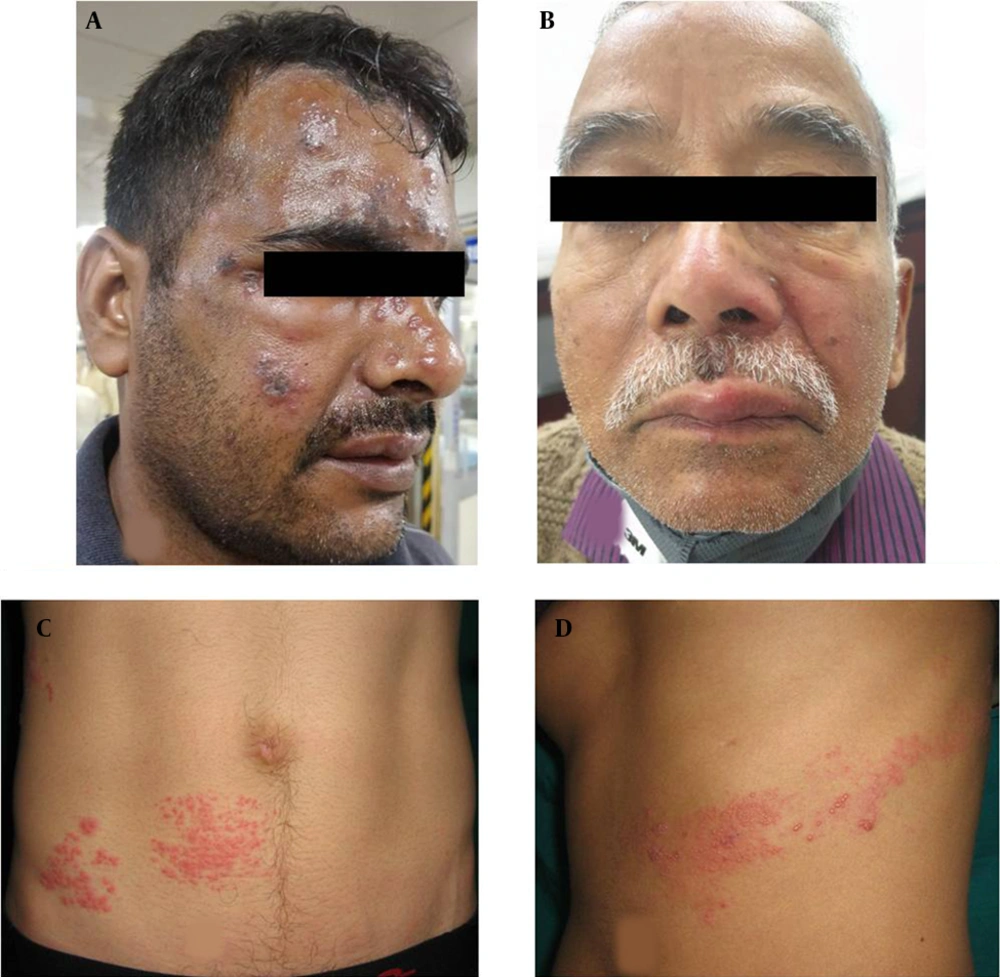

The PHN occurred in 41 cases (21.5%), including 23 and 18 male and female patients, respectively. Among the aforementioned subjects, 33 cases (80%) were above 60 years of age. These patients presented mainly with continuous deep nagging and intermittent pricking sensation or lancinating pain with allodynia. The thoracic segment was most commonly involved, followed by the trigeminal nerve in PHN. The extension of pain beyond dermatome was not observed. Furthermore, it was observed that 56% of PHN cases had coexistence of the above-mentioned complications. Interference with sleep was observed in 20% of cases leading to constant fatigue and interference with daily activities, especially in patients over 70 years of age and more in females. In follow-up, PHN persisted up to 6 months in 29 (70%) of the total PHN cases. Out of these 29 cases, among whom PHN persisted beyond 6 months, 23 subjects were above 60 years of age. Figure 1A - C, and d depict the clinical images of the involvement of different dermatomes. Figure 2A - C, and d illustrate the complications observed in HZ cases.

Clinical images of different morphological forms of herpes zoster; A, Illustrating herpes zoster ophthalimicus in right side; B, Illustrating herpes zoster involving maxillary branch of trigeminal nerve; C and D, Illustrating herpes zoster involving T11 right and T7 dermatomes, respectively.

Clinical images illustrating different complications of herpes zoster; A, Illustrating severe necrosis of skin following herpes zoster ophthalmicus; B, Illustrating abscess and scarring following herpes zoster of T6 dermatome left side; C, Illustrating severe oedema of both eyelids of left side; This patient had corneal ulceration which is not observed in the image.

5. Discussion

The HZ constitutes a sizable burden that is 0.84% of total dermatology cases in a tertiary care center. This study involving 190 consecutive cases of HZ revealed that a majority of the affected patients were adults, with 53% of patients being younger than 50 years of age. Nevertheless, the majority of studies have demonstrated an age-dependent increase in the incidence of HZ, chiefly attributable to the progressive decline in cell-mediated immunity to the VZV (6-10). The obtained data of the present study suggest that HZ is not only a disease of the elderly. Other studies, such as those performed by Abdul Lateef and Pavithran (11), Pavithran (12), Sehgal et al. (13), and Chandrika and Tharini (14), have reported similar observations.

An increase in the incidence of HZ in a relatively younger age group has been attributed to a variety of factors. Brisson et al. (9), through a mathematical model of the VZV transmission, showed that mass childhood vaccination increases the incidence of HZ in individuals within the age range of 30 - 50 years. In another instance, a Chinese study described the increased incidence of HZ in a relatively younger group due to poor housing conditions poor diets due to urbanization (15). The current study, not a population-based study, failed to draw such a conclusion on the possible causes of a relatively higher incidence of HZ in younger adults.

Nearly two-thirds of the 190 consecutive HZ cases included in this study were male. The differences in the gender distribution of HZ cases in this study possibly stems from the fact that this hospital primarily caters to security personnel with mandatory reporting to the hospital in case of any illness and their dependents correspondingly.

Male preponderance has been reported in certain studies from India, Nepal, and Pakistan (14, 16, 17). This finding is in contrast to the findings of western studies (18, 19) where both male and female subjects have been observed to be equally affected. Trauma and physical exertion could be the possible risk factors contributing to the male preponderance of HZ in the Indian setup (11, 20-22). A population-based study carried out in Korea by Kim et al. (10) showed a female preponderance. Higher female incidence, as reported in the literature, could probably be due to differences in the immune response to latent virus (23, 24).

Other possible risk factors of HZ have been described in the literature. Family history as a likely risk factor has been recently reported by Lai and Yew (20) as observed in 2.6% of cases. Although HZ does not occur following VZV exposure, physical and mental stress, surgical history, and recent fever episode might be predisposing factors (11, 20-22). Immune suppression in the form of steroid intake (n = 17), malignancies (n = 10), diabetes mellitus (n = 35), and HIV (n = 11 diagnosed cases, n = 2 newly diagnosed cases) as provoking factors was commonly (40% cases) observed. Depressed cellular immunity in these conditions could be a possible factor for the development of HZ (25). Immune suppression, as per available literature, is also associated with extensive involvement and serious complications (26).

More than half of the total number of cases occurred during the summer months (i.e., April - June). Increased incidence during the summer, as observed in the present study, could be explained by the reactivation of latent infection on exposure to varicella virus as chickenpox is also common during the summer (17). However, this finding contradicts the hypothesis of HZ risk reduction through exposure to chickenpox patients. This exogenous boosting hypothesis states that re-exposure to circulating VZV can inhibit viral reactivation and consequently HZ in VZV-immune individuals, which is also the basis for varicella-zoster vaccination (27). Meanwhile, certain studies have documented no significant seasonal variation of HZ (10, 28).

Constitutional symptoms were observed in 25% of cases as per previous Indian study (12, 19) but in contrast to high incidence studies conducted in South India in 2011 (11, 14). In accordance with the previous literature reports (20, 29, 30), pain followed by the vesicular eruption was noticed in most of the cases (90%), including in the present study. The incidence of prodrome was observed to be higher in the current study than in other studies (11). Prodrome was more evident in patients aged more than 60 years. Rash was more severe in cases who were above 50 years of age. These observations corroborate previous reports (16, 29). Eleven cases were asymptomatic with mild discomfort, and seven had neuralgia without vesicular eruptions (zoster sine herpete), as also observed in a study by Wollina (31). Persistent hiccups preceding HZ in the present study were observed in one patient, a presentation similar to that described by Reddy et al. as a rare prodromal manifestation of HZ (32).

In the current study, the thoracic segment was most commonly involved, followed by cranial nerve involvement, a similar distribution also reported in other studies (14, 30, 33). The pattern of dermatomal involvement was slightly different from those of certain previous Indian studies that reported cranial or lumbar segments as the most commonly involved (6, 7, 16). Among the cranial nerves, the trigeminal nerve was involved in 28 patients, and 1 patient developed Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Overall, 17 patients had HZO, 4 of whom had corneal involvement, less than the literature with 20 - 70% eye involvement in HZO (34). No case of disseminated HZ characterized by 20 vesicles away from primary or adjacent dermatome was observed during this period.

Neurological complications, including herpes zoster myelitis, segmental zoster paresis, and acute urinary retention (35-37), were not noticed in the present study. The PHN was observed in 21.5% of cases, 80% of whom were over 60 years of age. There was female predilection with 60% of cases as observed in previous studies (28, 38). The diagnosis of PHN was considered after 3 months of persistent neuralgia postdiagnosis of HZ. The incidence of PHN observed in the current study is higher than earlier studies and other investigations in the literature (8, 12, 39). Gauthier et al. reported that 19.5% and 13.7% of HZ patients develop PHN1 (pain persisting at least 1 month after rash onset) and PHN3 (pain persisting at least 3 months after rash onset), respectively (38).

The increased incidence of PHN in the present study might be due to long-term 6-month follow-up and the increased life expectancy. In the current study, PHN affected thoracic dermatome, compared to ophthalmic in a study by Jung et al. (40). It was more common in cases with initial greater acute pain severity, as observed by Jung (40). Some patients had temporary cessation of pain return after a few weeks in accordance with a few previous studies (39). The extension of pain beyond dermatome as reported in a study was not observed in the present study’s cases (41). A single case of HZO developed trigeminal neuralgia as reported in two studies (42, 43).

The HZ presented features in two HIV patients out of 11 cases. The HZ is associated with HIV diagnosis and is included as a stage II marker of the World Health Organization staging (44). A decline in CD4+ cells and an increase in CD8+ cells in HIV patients lead to a higher incidence of HZ in these patients (44). Patients with risk behaviours of HIV infection should receive regular surveillance for undiagnosed HIV infection when they present with HZ (45, 46).

Multidermatomal involvement with secondary infection was observed in two patients. The recurrence was noticed in two cases; however, unusual morphologies as reported in previous studies (16, 47) were not observed in the current study.

Diabetes and hypertension were freshly detected in 3 cases, each demonstrating HZ as an indicator of the existing disease. Few studies documented the association between diabetes and HZ (48). It is required to perform further studies in this regard. Despite other studies, no cerebrovascular accidents and myocardial infarction were noted. The increased risk of central nervous system infection has been noted following 3 - 12 months of HZ in a few population-based studies (49).

5.1. Conclusions

The HZ constituted 0.84% of total dermatology OPD in 6 months and reflected the sizable burden of HZ in a tertiary care centre. The presence of this disease in a relatively young population or in the male gender might be attributed to the demographic characteristics of the dependent clientele. Most cases were observed during the summer months of April - June. The thoracic segment followed by the trigeminal segment was most commonly affected. There was a high incidence of PHN (21.5%) in prolonged follow-up. The PHN mainly involves the thoracic dermatome, and more than half of the PHN cases were associated with complications, including secondary bacterial infection, severe ulceration, keloid and scarring, motor weakness, trigeminal neuralgia, and eye involvement.