1. Background

The concept of beauty in humans has been explained through different psychosocial dimensions. The psychosocial perspective views beauty in a broader psychosocial context and argues that beauty, especially a stereotype for women, is essential for social recognition and is associated with several positive attributes (e.g., high intelligence, social competence, friendliness, likeability, and leadership skills) (1). Being and staying beautiful and attractive also cause several biopsychosocial problems. People regard such problems as skin-related or medical problems and usually consult dermatologists or cosmetic dermatologists to overcome these problems. The field of cosmetic dermatology has been expanding and realizing the role of mental conditions involved for the patients of cosmetic dermatology. Psychodermatology has been an emerging field in this regard, which merges cosmetic dermatology and clinical psychology. The existing clinical psychology, however, does not address beauty-related specific mental conditions. The current study was initiated after my frequent clinical observations of women with anxiety related to getting unattractive (2). I tried to find a proper label for this condition. While exploring the clinical aspects of “fear of unattractiveness,” I explored the diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) (3) and examined the symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder, other specified obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, and adjustment disorders. Apart from the DSM-5, I also explored 2 other conditions mentioned in the literature: Gerascophobia (4) and Dorian Gray syndrome (5). I concluded that the understudied concept (i.e., fear of unattractiveness due to social pressure resulting in lower self-esteem, anxiety, sense of failure, and sense of being ostracized) was not given an appropriate label and could be explored further. Therefore, the term charismaphobia was coined as a new mental condition that involves all the relevant symptoms prevalent in the patients of cosmetic dermatology (2).

Charismaphobia intends to comprehend all the unattractiveness-related symptoms under 1 label by differentially excluding the related mental conditions (e.g., body dysmorphic and dysmorphic-like disorders, adjustment disorders, gerascophobia, and Dorian Gray syndrome). Charismaphobia, as simply defined in the current study, is the fear of unattractiveness. It can be present in both men and women. It further includes 2 conditions: (a) fear of being unattractive; and (b) fear of getting unattractive (after being regarded as attractive earlier in life). The criterion and judgment for attractiveness, in both these conditions, are obtained through social recognition. The clinical symptoms of charismaphobia (2) include the excessive and persistent presence of the following items:

a. Having a strong desire to be socially appreciated for physical attractiveness and bodily features alone

b. Having a strong desire to dominate others through physical attractiveness alone

c. Having a strong desire to look significantly younger than the chronological age

d. Having a strong belief to be comparatively better than others based on physical attractiveness and bodily features alone

e. Spending unjustified time on the internet to follow the latest fashion trends

f. Being extremely sensitive and selective in dressing

g. Having anxious thoughts about being regarded as unattractive by others

h. Taking medically unjustified measures to get or stay attractive

The excessive nature of the presence of the symptoms discussed above can be calculated by the norms established in the study (Table 1) or by conducting similar studies in one’s own culture. The recommended persistent nature of the presence of the symptoms discussed above is 6 months (i.e., the required symptoms need to be present for the last 6 months to be labeled as charismaphobic). Furthermore, the presence of symptoms g and h is mandatory to label a person with charismaphobia. These symptoms are related to charismaphobic anxiety, which is the main theme of charismaphobia.

| Variables | Items | α | Mean ± SD | % | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential | Actual | |||||||

| Phase 3 (n = 1407) | ||||||||

| Charismaphobia | 19 | 0.939 | 70.319 ± 17.116 | 74.020 | 19 - 95 | 19 - 94 | -1.058 | 0.038 |

| Exhibition | 3 | 0.784 | 11.366 ± 2.941 | 75.773 | 3 - 15 | 3 - 15 | -1.239 | 1.011 |

| Narcissistic trends | 3 | 0.735 | 9.890 ± 3.329 | 65.933 | 3 - 15 | 3 - 15 | -0.497 | -0.799 |

| Media consumption | 5 | 0.891 | 18.339 ± 5.727 | 73.356 | 5 - 25 | 5 - 25 | -0.873 | -0.473 |

| Anxiety | 8 | 0.952 | 30.723 ± 8.851 | 76.808 | 8 - 40 | 8 - 40 | -1.134 | 0.133 |

| Phase 4 (n = 988) | ||||||||

| Charismaphobia | 19 | 0.843 | 52.167 ± 14.226 | 54.913 | 19 - 95 | 20 - 91 | 0.216 | -0.559 |

| Exhibition | 3 | 0.802 | 8.775 ± 3.665 | 58.500 | 3 - 15 | 3 - 15 | -0.089 | -1.197 |

| Narcissistic trends | 3 | 0.756 | 9.430 ± 3.495 | 62.867 | 3 - 15 | 3 - 15 | -0.322 | -1.130 |

| Media consumption | 5 | 0.860 | 15.109 ± 6.357 | 60.436 | 5 - 25 | 5 - 25 | -0.132 | -1.242 |

| Anxiety | 8 | 0.904 | 18.852 ± 8.717 | 47.130 | 8 - 40 | 8 - 40 | 0.556 | -0.724 |

| Phases 3 and 4 combined (n = 2395) | ||||||||

| Charismaphobia | 19 | 0.926 | 62.831 ± 18.313 | 66.138 | 19 - 95 | 19 - 94 | -0.312 | -1.116 |

| Exhibition | 3 | 0.820 | 10.297 ± 3.500 | 68.647 | 3 - 15 | 3 - 15 | -0.701 | -0.621 |

| Narcissistic trends | 3 | 0.745 | 9.700 ± 3.405 | 64.667 | 3 - 15 | 3 - 15 | -0.425 | -0.954 |

| Media consumption | 5 | 0.882 | 17.006 ± 6.201 | 68.024 | 5 - 25 | 5 - 25 | -0.543 | -1.009 |

| Anxiety | 8 | 0.953 | 25.826 ± 10.560 | 64.565 | 8 - 40 | 8 - 40 | -0.306 | -1.352 |

2. Objectives

The current study aimed to develop and validate a scale to measure charismaphobia based on the symptoms already identified.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This quantitative study was conducted on 2904 participants from Islamabad and Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Initial interviews were conducted with 62 women (purposively selected women among my clients for psychotherapy), 30 cosmetic dermatologists, and 73 beauticians in the first phase of the study. The second phase of the study (i.e., the development and principal component analysis) involved 344 conveniently selected participants (101 men and 243 women). The third phase of the study (exploratory factor analysis (EFA)) involved 1407 conveniently selected participants (427 men and 980 women). The fourth phase of the study (confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and convergent validity) involved 988 conveniently selected participants (62 men and 926 women). All the participants were conveniently included in the studies with only 1 condition: They could respond to the questionnaire in English. Participants' educational qualifications ranged from college-level education to a doctorate.

The average educational qualification of the participants was graduation from university. Participants' age ranged from 18 to 75 years. The mean age of the participants was 28 years.

3.2. Instruments

A semi-structured clinical interview sheet was used in the first phase of the study. The main objective of these interviews was to identify the possible habits and psychopathological behaviors in relation to the fear of unattractiveness. Based on the findings of the first phase of the study, a new scale (Charismaphobia Scale) was developed in the second phase of the study and validated in the third and fourth phases of the study. The generalized anxiety disorder assessment 7 (GAD-7) (6), Narcissistic Personality Inventory 16 (NPI-16) (7), and short version of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (8) were used to measure the convergent validity of the Charismaphobia Scale.

3.3. Procedure

Data for the first phase of the study were gathered by me in a private clinic. I did clinical interviews with the purposively selected private clients. Interviews with cosmetic dermatologists and beauticians were also carried out in this regard. I involved some students to gather data for the second, third, and fourth phases of the study. The participants were approached in various public offices, hospitals, clinics, and educational institutions. Data were collected from January 2021 to September 2022. The Departmental Ethics Review Committee of the Department of Humanities at COMSATS University, Islamabad, Pakistan, approved this study. Data collection procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

3.4. Analysis

SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to record and analyze the data. Data were cleaned before analysis. The main analyses carried out in the current study were EFA and CFA.

4. Results

The initial scale comprised 37 items and was presented to a panel of 5 clinical psychologists to determine its face validity, which was found accurate. The response format was based on a 5-point Likert scale, including extremely false to extremely true. The participants were requested to provide their answers considering the last 6 months. Eighteen items were discarded in the second phase of the study (principal component analysis) due to their statistical weaknesses. The third and fourth phases of the study (i.e., EFA and CFA) tested and validated the remaining 19 items of the scale.

The EFA and CFA were performed using SPSS version 23. The principal component analysis and varimax method were used for extraction and rotation. Sampling adequacy, using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) values (9), was found marvelous in phase 3 (KMO = 0.946) and meritorious in phase 4 (Table 2; KMO = 0.871). The adequacy of correlations between items was analyzed through the Bartlett test of sphericity (10). It was highly significant in phases 3 and 4 (Table 2; P = 0.000).

Abbreviations: KMO, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin; BTS, Bartlett test of sphericity; EFA, exploratory factor analysis; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis.

a P = 0.000.

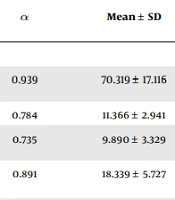

The Cronbach α reliability for the scale was excellent in phase 3 (α = 0.939) and good in phase 4 (Table 2; α = 0.843). Cronbach α values for the subscales ranged from 0.735 to 0.952 in phase 3 and from 0.756 to 0.904 in phase 4 (Table 1). Four factors were extracted with 72.15% variance explained in phase 3 and with 64.90% variance explained in phase 4 (Table 2). These factors were labeled as exhibition, narcissistic trends, media consumption, and anxiety (Table 3). The communalities for all 19 items ranged from 0.426 to 0.841 (Table 4) in phases 3 and 4 and were acceptable as all were above 0.4 (11). The item-total and item-scale correlations were highly significant for all 19 items (Table 4) in phases 3 and 4. The convergent validity of the Charismaphobia Scale with a generalized anxiety disorder (Table 5; r = 0.327; P < 0.001), obsessive-compulsive disorder (Table 5; r = 0.344; P < 0.001), and narcissistic personality disorder (r = 0.250; P < 0.001) was highly significant. The exploratory and confirmatory validations of the scale revealed that the Charismaphobia Scale was sufficiently reliable and valid to be used further.

| Item No. | Item | EFA | CFA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exh | Nar | Med | Anx | Exh | Nar | Med | Anx | ||

| 1 | I want to be liked by all because of my bodily features and physical attractiveness. | 0.769 b | 0.049 | 0.192 | 0.265 | 0.833 b | 0.005 | 0.088 | 0.150 |

| 2 | I want to be appreciated by all because of my physical attractiveness. | 0.808 b | 0.118 | 0.151 | 0.253 | 0.861 b | 0.013 | 0.069 | 0.154 |

| 3 | I want others to give me good comments on my physical attractiveness. | 0.694 b | 0.101 | 0.179 | 0.346 | 0.776 b | -0.026 | 0.077 | 0.163 |

| 4 | I want to be admired by all. | 0.052 | 0.849 b | 0.093 | 0.150 | 0.006 | 0.845 b | 0.018 | -0.055 |

| 5 | I want to be the most attractive person. | 0.092 | 0.845 b | 0.164 | 0.122 | -0.042 | 0.875 b | 0.024 | -0.009 |

| 6 | I am a special person with a unique attraction. | 0.140 | 0.541 b | 0.376 | 0.265 | 0.018 | 0.734 b | -0.005 | -0.027 |

| 7 | I usually watch advertisements related to beauty and fashion. | 0.121 | 0.063 | 0.802 b | 0.247 | 0.082 | 0.031 | 0.692 b | 0.164 |

| 8 | I remain interested in finding new beauty products to improve my attraction. | 0.129 | 0.140 | 0.824 b | 0.334 | 0.141 | -0.002 | 0.823 b | 0.157 |

| 9 | I usually spend a significant amount of money to buy beauty products. | 0.202 | 0.205 | 0.674 b | 0.359 | 0.081 | 0.024 | 0.808 b | 0.072 |

| 10 | I have subscribed to many beauty channels and blogs on social media. | 0.157 | 0.125 | 0.797 b | 0.293 | -0.010 | 0.006 | 0.777 b | 0.139 |

| 11 | I usually search the internet to find the best beauty products. | 0.127 | 0.160 | 0.695 b | 0.119 | 0.014 | -0.020 | 0.837 b | 0.084 |

| 12 | I feel worried when I think my physical attractiveness may decline with the passage of time. | 0.263 | 0.092 | 0.323 | 0.734 b | 0.207 | -0.057 | 0.211 | 0.703 b |

| 13 | I feel annoyed when I think I will be useless when I get older. | 0.118 | 0.128 | 0.301 | 0.823 b | 0.048 | 0.026 | 0.080 | 0.823 b |

| 14 | I feel worried when I think I will lose my value by getting older. | 0.165 | 0.128 | 0.238 | 0.846 b | 0.058 | 0.016 | 0.103 | 0.837 b |

| 15 | I feel sad when I think people will not appreciate my physical attractiveness when I will get older. | 0.210 | 0.125 | 0.288 | 0.835 b | 0.199 | -0.017 | 0.128 | 0.791 b |

| 16 | I am afraid to get older. | 0.240 | 0.197 | 0.172 | 0.745 b | 0.005 | -0.030 | 0.026 | 0.770 b |

| 17 | It hurts me when I think I am getting older day by day. | 0.249 | 0.185 | 0.138 | 0.776 b | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.046 | 0.788 b |

| 18 | I cannot think of being unattractive. | 0.245 | 0.068 | 0.255 | 0.747 b | 0.190 | -0.068 | 0.196 | 0.589 b |

| 19 | It hurts me when I think I will be considered unattractive in the future. | 0.220 | 0.133 | 0.257 | 0.813 b | 0.187 | -0.062 | 0.136 | 0.760 b |

Abbreviations: EFA, exploratory factor analysis; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; Exh, exhibition; Nar, narcissistic trends; Med, media consumption; Anx, anxiety.

a Extraction method: Principal component analysis. Rotation method: Varimax.

b These values represent the factor structure.

| Item No. | EFA | CFA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction | Item-Total and Item-Scale Correlations | Extraction | Item-Total and Item-Scale Correlations | |||||||||

| Chr | Exh | Nar | Med | Anx | Chr | Exh | Nar | Med | Anx | |||

| 1 | 0.701 | 0.581 a | 0.833 a | 0.724 | 0.464 a | 0.847 a | ||||||

| 2 | 0.754 | 0.589 a | 0.862 a | 0.770 | 0.468 a | 0.877 a | ||||||

| 3 | 0.643 | 0.616 a | 0.811 a | 0.636 | 0.444 a | 0.815 a | ||||||

| 4 | 0.754 | 0.453 a | 0.816 a | 0.718 | 0.165 a | 0.830 a | ||||||

| 5 | 0.765 | 0.487 a | 0.850 a | 0.768 | 0.191 a | 0.863 a | ||||||

| 6 | 0.524 | 0.611 a | 0.758 a | 0.540 | 0.160 a | 0.767 a | ||||||

| 7 | 0.723 | 0.667 a | 0.838 a | 0.514 | 0.541 a | 0.734 a | ||||||

| 8 | 0.826 | 0.765 a | 0.907 a | 0.721 | 0.615 a | 0.840 a | ||||||

| 9 | 0.666 | 0.748 a | 0.825 a | 0.664 | 0.534 a | 0.804 a | ||||||

| 10 | 0.762 | 0.728 a | 0.875 a | 0.622 | 0.535 a | 0.792 a | ||||||

| 11 | 0.539 | 0.556 a | 0.719 a | 0.709 | 0.530 a | 0.832 a | ||||||

| 12 | 0.720 | 0.800 a | 0.845 a | 0.586 | 0.676 a | 0.764 a | ||||||

| 13 | 0.798 | 0.810 a | 0.884 a | 0.686 | 0.645 a | 0.810 a | ||||||

| 14 | 0.816 | 0.810 a | 0.899 a | 0.715 | 0.667 a | 0.827 a | ||||||

| 15 | 0.841 | 0.845 a | 0.916 a | 0.681 | 0.687 a | 0.810 a | ||||||

| 16 | 0.681 | 0.753 a | 0.818 a | 0.594 | 0.569 a | 0.760 a | ||||||

| 17 | 0.717 | 0.757 a | 0.839 a | 0.623 | 0.596 a | 0.776 a | ||||||

| 18 | 0.688 | 0.761 a | 0.829 a | 0.426 | 0.580 a | 0.661 a | ||||||

| 19 | 0.793 | 0.818 a | 0.891 a | 0.634 | 0.662 a | 0.796 a | ||||||

Abbreviations: EFA, exploratory factor analysis; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; Chr, Charismaphobia Scale; Exh, exhibition; Nar, narcissistic trends; Med, media consumption; Anx, anxiety.

a The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

| Exhibition | Narcissistic Trends | Media Consumption | Anxiety | Generalized Anxiety Disorder | Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | Narcissistic Personality Disorder | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charismaphobia | 0.542 a | 0.210 a | 0.688 a | 0.818 a | 0.327 a | 0.344 a | 0.250 a |

| Exhibition | -0.020 | 0.197 a | 0.328a | 0.133 a | 0.141 a | 0.217 a | |

| Narcissistic trends | 0.016 | -0.061 | 0.047 | -0.011 | 0.001 | ||

| Media consumption | 0.304 a | 0.208 a | 0.265 a | 0.193 a | |||

| Anxiety | 0.308 a | 0.313 a | 0.176 a | ||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.520 a | 0.116 a | |||||

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 0.197 a |

a The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

5. Discussion

The Charismaphobia Scale revealed 4 factors for charismaphobia (i.e., self-exhibition, narcissistic trends, media consumption, and anxiety). Anxiety is the core ingredient of charismaphobia, whereby a charismaphobic person would get abnormally anxious about missing relevant information on the internet or social media to get the latest updates on fashion and beauty trends. The charismaphobic anxiety can also be due to the lack of social admiration against one’s physical attractiveness. Generalized anxiety disorder, which has been found to be significantly and positively correlated with charismaphobia in the current study, also has similar symptoms, but the object of anxiety in generalized anxiety disorder is usually unknown (3). Charismaphobic anxiety, on the other hand, is a known anxiety developed for being or getting unattractive and involves sociocultural pressures. Having appreciable physical attractiveness and avoiding a disliked body image have been recognized as major health concerns worldwide (12). People who have these concerns at severe levels also develop several other problems, such as frequent dieting (13), bulimic symptoms and dietary restraint (14), weight gain (15), poorer psychological well-being (16), depression (17), and lower self-esteem (18). Studies have also shown that people who are more satisfied with their physical appearances and bodies possess higher self-esteem, psychological well-being, and sexual satisfaction (19). The earlier literature also provides sufficient evidence for a positive connection between several dermatological conditions and mental disorders (12-18, 20-24). The patients who visit cosmetic dermatologists have almost 2 times more psychiatric symptoms than those who visit general dermatologists (20). Dermatologists must be aware of certain beauty-related psychological symptoms, such as body dimorphic disorder (2, 20), and should know about the mental health of their patients (21). Psychodermatology is a rapidly growing field that combines neurology, mind, and skin (25). Charismaphobia and Charismaphobia Scale would be valuable contributions to the field of psychodermatology as well.

The current research revealed that the presence of charismaphobia (i.e., the fear of being or getting unattractive) would also require people to indulge in excessive and persistent media consumption to explore the latest trends in fashion and beauty. Media plays a critical role in the development of body image in both men and women. Media has a proven role in changing perceptions of beauty (26), inducing age-related fear in public (27), constantly showing negative images of growing old to provide the marketed strategies to avoid aging (28), promoting the businesses of anti-aging products with the idea that beauty is strongly associated with youth (29), building rapport between cosmetic producers and consumers (30), presenting females as sex bombs by unrealistically editing pictures and videos of women through software (31), promoting eating disorders (32), decreasing self-reliance and decision making, and promoting body dissatisfaction (33). Media affects men and women (34) directly and indirectly (35). Women, however, take this effect more seriously (36). Media promotes cosmetic surgeries (20), and celebrity idealization is one of the strongest reasons for undergoing cosmetic surgery (37). Social media is more interactive than traditional media in developing beauty standards (34).

Self-exhibition and narcissistic trends are also essential aspects of charismaphobia through which people desire to be socially appraised for their physical attractiveness. The association between pleasing appearances and positive human qualities is also a cross-cultural trend (38). People considered unattractive in society are also regarded to have negative personality traits (1). By labeling individuals as socially unattractive, societies cause several psychosocial issues for those who do not meet the established standards of attraction in society. These issues include low self-esteem (39) and poor physical and psychological health (22). Body image (i.e., how one perceives one's own body) is an important part of a good life, and a negative body image can result in destructive behaviors (12). A positive body image results in better and more efficient outcomes, such as life satisfaction and happiness (40). Therefore, people all over the world spend a huge amount of money on their desire to stay young and attractive (i.e., by purchasing anti-aging products) (41).

The present research brings charismaphobia to the attention of dermatologists and other relevant professionals. It also highlights the importance of being attuned to the mental health of the patients. The Charismaphobia Scale, developed and validated during the current study, would be a useful tool for researchers, clinical psychologists, and cosmetic dermatologists. The scale would enable them to screen out the mental conditions underlying the dermatological problems.