1. Background

Physical attractiveness is regarded as an important aspect of mental health and life satisfaction worldwide. Earlier studies have established that physically attractive individuals are more liked in almost all cultures. They have better opportunities and are more satisfied with life (1-5). Conversely, physically less attractive individuals face several psychosocial problems, including body dissatisfaction, body shaming, self-hate, charismaphobia, low self-esteem, depression, social withdrawal, and loneliness (6-10).

Self-esteem is a fundamental concept in psychology and has been approached and defined from various angles, reflecting its complex nature. It has been viewed as an indicator of an individual's perceived capability to achieve life goals (11), the degree to which a person values oneself, encompassing positive self-evaluations and self-respect (12-14). Self-esteem involves a personalized assessment of one's worthiness as an individual, incorporating sentiments of self-acceptance (15). It can also be related to competence, worth, performance, social acceptance, and physical well-being (16). Self-esteem is grounded in a strong sense of self, expressed through action, initiative, and an intrinsic sense of worth (17). Theorists also categorize self-esteem into trait self-esteem, which represents an individual's average sense of self-worth stable across situations and time, and state self-esteem, which is situational and fluctuates due to various factors such as recent successes or failures, acceptance, or rejection (18).

The development of self-esteem has been extensively researched. While family interactions were once considered primary (19), it is now understood that childhood experiences, and reactions from family, teachers, classmates, and authorities all shape our basic self-esteem (20). Research indicates that approximately half of our personality and feelings of self-worth are inherited, with environmental factors playing a substantial role (21, 22). Behavioral genetic studies suggest a joint influence of genes and environment on self-esteem, with environmental factors exerting slightly stronger effects (22). Self-esteem functions as an internal mechanism, monitoring social attachments to inspire behaviors that fulfill the basic desire for social belonging (23). It also acts as a psychological defense mechanism, protecting humans from the existential anxiety arising from the awareness of mortality (24).

Body-esteem is also a key aspect of self-representation and self-evaluation (25). Body-esteem is regarded as the level of contentment with one's current physical self, encompassing aspects like size, shape, and overall appearance (26). It reflects how aesthetically and sexually appealing an individual believes their body to be in the eyes of others (27). Factors involved in body-esteem mostly include physical attractiveness, involving important facial and bodily features such as skin tone, facial symmetry, body weight, Body Mass Index, waist-to-hip ratio, body shape, and baby-like features (28, 29). External feedback and reactions play a fundamental role in shaping one's body-esteem (30). Body-esteem is an important contributor to the overall self-esteem of a person (31).

Charismaphobia is a recently coined mental condition that refers to an excessive and persistent fear of being or becoming unattractive (9). Symptoms include a strong desire to be socially appreciated solely for physical attractiveness and bodily features; a strong desire to dominate others through physical attractiveness alone; a strong desire to look significantly younger than one's chronological age; a strong belief in being comparatively better than others based on physical attractiveness and bodily features alone; spending excessive time on the internet following the latest fashion trends; being extremely sensitive and selective in dressing; having anxious thoughts about being regarded as unattractive by others; and taking medically unjustified measures to become or stay attractive (8). As a new phenomenon, charismaphobia has not been studied extensively in combination with its related psychosocial factors.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to analyze the role of body-esteem and self-esteem in charismaphobia, along with measuring differences between men and women.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This survey involved 879 conveniently selected participants from Islamabad, Pakistan, including both men (n = 261) and women (n = 618). Since the participants were selected through a convenient sampling technique, more women than men were willing to participate in the survey. This disproportionate sample has been appropriately addressed by calculating Cohen’s d while comparing men and women. The participants' ages ranged from 18 to 75 years, with a mean age of 32 years. The educational qualifications of the participants ranged from matriculation (10 years of formal education) to a doctorate, with the mean educational qualification being graduation (14 years of formal education).

3.2. The Instruments

The Charismaphobia Scale (9) was used to measure the fear of being or becoming unattractive. The scale comprises 19 items with a 5-point Likert-type response format ranging from "extremely false" to "extremely true." It is categorized into four sub-scales: Self-exhibition, narcissistic trends, media consumption, and anxiety. The developer of the scale established its strong reliability and validity through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (9). The Self-Esteem Scale (32) and the Body-Esteem Scale (25) were also used. Both scales have been proven reliable and valid in various studies. Additionally, a demographic information questionnaire was employed to collect data on the gender and age of the participants.

3.3. Procedure

The study received approval from the Departmental Ethics Review Committee at (blinded) University. The data collection procedures strictly adhered to the principles outlined in the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its subsequent revisions. Prospective participants were recruited from various educational institutions, hospitals, clinics, and public offices. Before their involvement, participants were provided with comprehensive information about the study's objectives, and their consent to participate was obtained ethically. Participants were also guaranteed confidentiality regarding their data and were sincerely thanked for their valuable contributions to the research.

3.4. Analysis

The collected data was entered and organized using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS). To assess the reliability of the instruments, Cronbach's alpha was calculated. Pearson correlation coefficient, t-test, Cohen’s d, regression analysis, and descriptive statistics were used to finalize the results.

4. Results

The instruments used in the study demonstrated excellent reliability (Table 1 α = 0.951 for the Charismaphobia Scale, 0.846 for the Self-Esteem Scale, and 0.925 for the Body-Esteem Scale). The level of charismaphobia was found to be significantly higher in women compared to men (Table 2 Men = 52.53% vs. Women = 68.04%; P = 0.000; Cohen’s d = 0.710). Conversely, men had significantly higher levels of body-esteem (Table 2 Men = 80.03% vs. Women = 70.37%; P = 0.000; Cohen’s d = 1.040) and self-esteem (Table 2 Men = 68.85% vs. Women = 53.69%; P = 0.000; Cohen’s d = 0.985) compared to women.

| Variables | Items | α a | Mean ± SD | % | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential | Actual | |||||||

| Charsimaphobia | 19 | .951 | 61.049 ± 17.937 | 64.26 | 19 - 95 | 27 - 92 | -0.331 | -1.215 |

| Self esteem | 10 | .846 | 23.277 ± 6.749 | 58.19 | 10 - 40 | 12 - 38 | 0.054 | -1.119 |

| Body esteem | 35 | .925 | 128.171 ± 18.001 | 73.24 | 35 - 175 | 93 - 165 | 0.011 | -1.073 |

a α = Cronbach’s Alpha.

| Variables | Men (n = 261) | Women (n = 618) | t (877) | P-Value | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | % | Mean ± SD | % | ||||

| Charismaphobia | 52.533 ± 18.683 | 55.29 | 64.646 ± 16.344 | 68.04 | 9.613 | 0.000 | 0.710 |

| Self esteem | 27.540 ± 6.255 | 68.85 | 21.476 ± 6.115 | 53.69 | 13.341 | 0.000 | 0.985 |

| Body esteem | 140.065 ± 13.503 | 80.03 | 123.148 ± 17.296 | 70.37 | 14.090 | 0.000 | 1.040 |

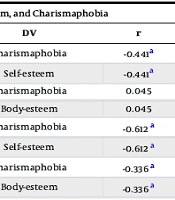

A significant inverse correlation was found between charismaphobia and body-esteem (Table 3 r = -.329; P < 0.01), as well as between charismaphobia and self-esteem (Table 3 r = -.608; P < 0.01). To analyze the direction of the effects between these variables, simple regression analysis was performed. Self-esteem affected charismaphobia more (Table 3 B = -1.318 in men & -1.637 in women; P = 0.000) than charismaphobia affected self-esteem (Table 3 B = -0.148 in men & -0.229 in women; P = 0.000) in both men and women. The effects between charismaphobia and body-esteem were not as significant. A slight difference was found among women, whereby charismaphobia affected body-esteem slightly more (Table 3 B = -0.356; P = 0.000) than body-esteem affected charismaphobia (Table 3 B = -0.318; P = 0.000).

| Variables | IV | DV | r | B | SE B | β | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Self-esteem | Charismaphobia | -0.441 a | -1.318 | 0.167 | -0.441 | -7.913 | 0.000 |

| Charismaphobia | Self-esteem | -0.441 a | -0.148 | 0.019 | -0.441 | -7.913 | 0.000 | |

| Body-esteem | Charismaphobia | 0.045 | 0.062 | 0.086 | 0.045 | 0.722 | 0.471 | |

| Charismaphobia | Body-esteem | 0.045 | 0.032 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.722 | 0.471 | |

| Women | Self-esteem | Charismaphobia | -0.612 a | -1.637 | 0.085 | -0.612 | -19.228 | 0.000 |

| Charismaphobia | Self-esteem | -0.612 a | -0.229 | 0.012 | -0.612 | -19.228 | 0.000 | |

| Body-esteem | Charismaphobia | -0.336 a | -0.318 | 0.036 | -0.336 | -8.863 | 0.000 | |

| Charismaphobia | Body-esteem | -0.336 a | -0.356 | 0.040 | -0.336 | -8.863 | 0.000 |

a Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

As indicated by the correlations above, the relationship between charismaphobia and self-esteem was comparatively stronger than the relationship between charismaphobia and body-esteem. This was confirmed by regression analysis, which showed that self-esteem was more relevant for charismaphobia (Table 4 β = -0.731 vs. 0.483 in men & -0.564 vs. -0.137 in women; P = 0.000) than body-esteem.

a P = 0.000.

5. Discussion

The modern world is marked by pervasive discrimination based on appearance, particularly concerning attractiveness. Research shows that individuals with lighter skin tones and better physiques tend to experience more success, education, and job opportunities (33). This phenomenon highlights the impact of societal beauty norms on individuals’ lives. For instance, taste-based discrimination in hiring processes illustrates that women are often chosen for their beauty, even at the expense of productivity (34). Societal norms have led to a scenario where people, especially women, feel compelled to conform to these standards, leading to significant identity struggles. Social recognition is often associated with mental health more than any other contributor (35). The pressure to conform to societal expectations has led people to engage in practices aimed at meeting these beauty standards.

Women face many challenges in this regard. From adhering to norms related to hair length and body hair removal to using makeup and undergoing cosmetic surgeries, the lengths to which women go to fit in are extensive (36). This social pressure extends to men as well, with the rise of beauty products catering specifically to them.

The present study investigated charismaphobia, specifically examining its gender-specific manifestations in relation to body-esteem and self-esteem. The research revealed interesting findings in this regard. Women exhibited significantly higher levels of charismaphobia compared to men, highlighting the societal pressure faced by women regarding their physical appearance (37, 38). This observation aligns with existing literature, where cultural norms dictate distinct standards of physical attractiveness for men and women (39). The phenomenon is further reinforced by the fact that women tend to seek cosmetic interventions more frequently than men (38, 40), indicating a heightened concern among women about being or becoming unattractive. Generally, women are more inclined toward social compliance (41) and report higher levels of several mental disorders compared to men (42).

In examining the factors contributing to charismaphobia, both self-esteem and body-esteem emerged as significant determinants. Self-esteem, encompassing a broader spectrum of human attributes and competencies, emerged as a potent predictor of charismaphobia. This finding aligns with prior research indicating that dissatisfaction with one’s body and physical appearance correlates with diminished self-esteem and body-esteem (43).

5.1. Implications and Recommendations

The rise of cosmetic dermatology as a medical subfield highlights the growing fusion of medical treatments with beauty standards. Cosmetic dermatologists employ a range of procedures, both surgical and non-surgical, to address individuals’ appearance-related concerns (44). However, this pursuit of aesthetic perfection is not without its challenges. Patient suitability for procedures, careful psychological assessment, and ethical considerations are paramount (45). Additionally, psychological disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder and charismaphobia can render cosmetic procedures ineffective and even worsen patients’ conditions (46). The emergence of psychoneurocutaneous medicine and psychodermatology signifies a shift towards addressing the psychological aspects of dermatological conditions (47). Addressing these challenges necessitates a comprehensive approach, combining ethical guidelines, psychological assessments, and societal awareness to ensure the psychosocial well-being of individuals in their pursuit of societal beauty standards.

For both men and women, relying solely on physical attractiveness as a measure of self-satisfaction is evidently harmful to mental health. Instead, fostering a holistic sense of self-worth, encompassing one's abilities, talents, and personal achievements, can serve as a buffer against the dangers of charismaphobia. Educators and mental health professionals should promote comprehensive self-esteem interventions that emphasize these diverse aspects of identity.

Cosmetic dermatologists play a crucial role not only in enhancing their clients' physical appearance but also in enlightening them about the complex psychosocial elements contributing to attractiveness. True beauty extends far beyond mere skin tone or physique; it encompasses emotional expressiveness and a captivating character. Therefore, it is imperative for these professionals to educate their clients comprehensively, emphasizing that attractiveness is a multifaceted trait, woven from both inner qualities and external features. By understanding and appreciating these deeper aspects, clients can truly embrace the essence of being beautiful or handsome.

5.2. Conclusions

In the pursuit of physical attractiveness, individuals often find themselves entangled in thoughts, attitudes, behaviors, and even medical procedures. This pursuit not only shapes their appearance but also paves the way for various psychodermatological issues, one of which is charismaphobia, i.e., the fear of becoming or being perceived as unattractive. The present paper addresses a critical gap in our understanding by exploring the intricate links between charismaphobia, self-esteem, and body-esteem. By analyzing these connections, this study offers fresh perspectives to mental health practitioners and cosmetic dermatologists alike.