1. Context

1.1. Definition of Morbihan Disease

Morbihan disease (MD), also known as lymphedema rosacea, solid persistent facial edema, Morbihan syndrome, and morbus Morbihan, is a rare condition characterized by chronic, progressive, asymptomatic non-pitting edema and/or erythema of the upper two-thirds of the face. This primarily affects the forehead, glabella, periorbital areas, cheeks, and nose, potentially leading to facial contour deformity and sometimes narrowing of the visual field (1-3).

1.2. History of Morbihan Disease

"Morbihan" refers to an area in France where the first French patient was diagnosed by dermatologist Dr. Robert Degos in 1957 (4).

1.3. Etiopathogenesis of Morbihan Disease

The etiopathogenesis of MD is still unknown. It has been suggested that MD results from lymphatic dysfunction, chronic cutaneous inflammation, or both. These hypotheses can be explained as follows:

- There is an imbalance between lymphatic synthesis and drainage (5).

- Increased dermal mast cell infiltrations could obstruct lymphatics or cause dermal fibrosis (3, 6).

- The presence of intra- and perilymphatic granulomas could obstruct lymphatic drainage (7).

- Chronic cutaneous inflammatory reactions, due to underlying autoimmune diseases or infections, release several inflammatory mediators, which could lead to cutaneous vascular damage and the breakdown of dermal connective tissue, resulting in persistent exudation and edema (8, 9).

- Contact urticaria from the use of topical irritants could trigger local inflammatory reactions, resulting in insufficient lymphatic drainage in patients with pre-existing lymphatic drainage defects (5, 10).

- There is a possible association between MD and diabetes mellitus, as diabetes can disrupt lymphatic vascular integrity through impairment of nitric oxide signaling (11).

The associations between rosacea, acne, and MD are still unclear. The relationship between MD, rosacea, and acne has been suggested due to histopathological similarities (8). However, several patients with MD do not have acne or rosacea (1, 2).

1.4. Clinical Presentations of Morbihan Disease

- Sex: Morbihan disease can affect both sexes. However, more cases are reported in men than in women (1, 3).

- Age: Morbihan disease primarily affects individuals in middle age (40 - 60 years old) (1, 3).

- Ethnicity: Most patients with MD are Caucasian, followed by Asians (Korean, Japanese, and Chinese) (1).

- Clinical Picture: Patients with MD typically present with asymptomatic, recurrent bilateral symmetrical pitting edema with an insidious onset and progressive course affecting the upper two-thirds of the face (forehead, glabella, periorbital area, cheeks, and nose) with or without erythema. This condition progressively evolves into persistent solid, non-pitting, asymptomatic edema (non-painful and non-pruritic), potentially causing facial contour deformities and sometimes narrowing of the visual field. Most patients do not exhibit systemic manifestations (1-3, 6, 10, 12, 13). There has been a report of a 46-year-old male presenting with unilateral swelling in the right infraorbital cheek area, diagnosed clinically and histopathologically as unilateral MD (14) (Table 1).

- Diagnosis: Morbihan disease has numerous morphological and histological overlaps with several granulomatous and inflammatory facial disorders, making diagnosis challenging. The key symptoms of chronic, localized facial edema and erythema suggest a wide range of differential diagnoses, including Hansen’s disease, sarcoidosis, angioedema, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, cutaneous leishmaniasis, foreign body granuloma, facial granuloma, superior vena cava syndrome, and scleredema of Buschke. Cutaneous drug reactions, particularly to barbiturates, chlorpromazine, and diltiazem, should also be considered (15).

- Mimickers: The most convincing mimickers for MD may be cutaneous inflammatory diseases with facial involvement, such as Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (6). The slow onset and chronic course of MD are essential clinical characteristics that can help differentiate it from other diseases (16).

1.5. Histopathology of Morbihan Disease

The classical histopathological features in the early stage of MD include localized lymphedema, the presence of dilated blood vessels, and perivascular and perifollicular inflammatory infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and mast cells. Recurrent and prolonged inflammatory responses can lead to dermal lymphatic vessel dilation, obstruction, and altered lymph drainage. Ultimately, non-pitting edema transitions into a persistent solid mass, indicating the formation of fibrotic induration and occasionally sarcoidal granulomas (6, 7). Immunohistochemical studies have shown D2-40 expression in lymphatic endothelial cells, which are considered the classical endothelial cell phenotype in MD. Additionally, CD68 can be used as a histological biomarker for MD to exclude carcinoma (6).

1.6. Diagnosis of Morbihan Disease

There are no specific criteria for diagnosing MD; therefore, the diagnosis is primarily based on clinical features, histopathology, and imaging information. These investigations are used to exclude other causes of facial edema (1, 3, 4, 6, 7). Recent advances in imaging may shed light on the anatomic alterations in the lymphatic system associated with MD. However, imaging has rarely been used in diagnosing MD. Cerebrofacial magnetic resonance imaging has been employed to exclude tumor compression or regional infectious factors as contributing mechanisms. Near-infrared imaging and non-invasive, contrast agent-free imaging systems (such as optical coherence tomography, optical frequency domain imaging, and multispectral imaging) could be essential tools for visualizing the lymphatic system and narrowing the broad differential diagnosis that currently challenges clinicians (10, 17, 18).

1.7. Treatment of Morbihan Disease

Currently, there are no controlled clinical studies on the treatment of MD due to the rarity of the disease; thus, its management remains primarily empirical. The uncertain etiopathogenesis limits the development of targeted treatments. Therapeutic regimens are classified into systemic, local, and surgical treatments.

1.8. Systemic Treatment

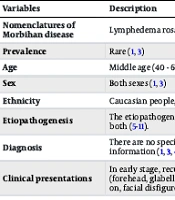

Therapeutic options mainly consist of systemic anti-inflammatory drugs, either given alone or in combination (1, 2, 17) (Table 1).

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| Nomenclatures of Morbihan disease | Lymphedema rosacea, solid persistent facial edema, morbus Morbihan, Morbihan syndrome (1, 3) |

| Prevalence | Rare (1, 3) |

| Age | Middle age (40 - 60 years old) (1, 3) |

| Sex | Both sexes (1, 3) |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian people, followed by Asian people (1) |

| Etiopathogenesis | The etiopathogenesis of Morbihan disease (MD) is still unknown. It may be due to lymphatic dysfunction, chronic cutaneous inflammation, or both (5-11). |

| Diagnosis | There are no specific criteria for diagnosis of MD. So, the diagnosis of MD is primarily based on clinical features, histopathology and imaging information (1, 3, 4, 6, 7). |

| Clinical presentations | In early stage, recurrent bilateral symmetrical pitting edema with insidious onset and progressive course on the upper two thirds of face (forehead, glabella, periorbital region, cheeks and nose) with or without erythema then persistent solid, non-pitting, asymptomatic edema. Later on, facial disfigurement and even visual field narrowing (1-3, 6, 10, 12, 13). |

| Histopathology | In early stage of MD, localized lymphedema, presence of dilated blood vessels, perivascular and perifollicular inflammatory infiltrations with lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and mast cells. Then, dermal lymphatic vessel dilation, obstruction, and lymph drainage alterations. Later on, fibrotic induration and sometimes sarcoidal granulomas (6, 7). |

| Treatment | There are no controlled clinical studies on treatment of MD, because of the rarity of the disease; so, its management remains mainly empirical (1, 2, 17). |

| Systemic treatment | Doxycycline 200 mg daily for 3 - 6.5 months (1, 19). Isotretinoin (10 - 20 mg per day) alone or with ketotifen (1 mg two times per day) for 3 - 6 months has been recoded to be effective (20, 21). Others drugs as diuretics, thalidomide, metronidazole, systemic steroids, clofazimine (22-24). Recently, omalizumab was successful treatment for MD (25). |

| Local treatment | Long‐term intralesional injection of triamcinolone (every 4 - 6 weeks for 4 months) for resistant MD (26). Local lymphedema management as compression therapy, manual lymphatic drainage, and skin care (27, 28). |

| Surgical treatment | Surgical debulking eyelid mass with triamcinolone injections (9). Blepharoplasty (29). |

| Prognosis | Without treatment, MD is improbable to improve spontaneously (3, 30). |

Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Morbihan Disease (MD)

The most commonly used drugs are tetracycline antibiotics (doxycycline or minocycline) and isotretinoin. Doxycycline is typically administered at 200 mg per day for 3 - 6.5 months (1, 19). Isotretinoin, at a dose of 10 - 20 mg per day, either alone or combined with ketotifen (1 mg twice a day) for 3 - 6 months, has been reported to be effective. However, responses may be uncertain (20, 21).

Additionally, several other drugs have been used for the treatment of MD with no or only short-term efficacy, such as diuretics (furosemide and spironolactone), thalidomide, metronidazole, systemic steroids, and clofazimine (22-24). Recently, omalizumab has shown success in the treatment of MD (25).

1.9. Local Treatment

Long-term intralesional injections of triamcinolone, administered every 4 - 6 weeks for 4 months, have been recorded as an effective, safe, and minimally invasive treatment for resistant MD of the upper and lower eyelids, particularly when mast cell infiltration is present (26).

Local management of lymphedema, including compression therapy, manual lymphatic drainage, and skin care, may effectively improve the condition of patients with MD (27, 28).

1.10. Surgical Treatment

Surgical debulking of the eyelid mass combined with triamcinolone injections has been reported as an effective management strategy for five patients with resistant MD (9). Additionally, CO2 laser blepharoplasty has proven to be an effective therapy for addressing visual impairment caused by MD progression, particularly in patients with pupillary axis obstruction (29).

1.11. Prognosis of Morbihan Disease

Without treatment, MD is unlikely to improve spontaneously. Therefore, early management is crucial for the well-being of the patient. Lack of awareness about MD progression from both the patient and physician, coupled with the absence of effective treatment, may contribute to the chronic progressive course of MD (13, 30).

2. Conclusions

Morbihan disease is a rare and infrequent disease characterized by asymptomatic, recurrent bilateral symmetrical pitting edema with an insidious onset and progressive course on the upper two-thirds of the face, with or without erythema. Over time, it evolves into persistent solid, non-pitting, asymptomatic edema (non-painful and non-pruritic). This condition may lead to facial contour deformity and sometimes narrowing of the visual field. The etiopathogenesis of MD is still unknown, and currently, there is no specific treatment for MD. This review article provides an update on MD, aiming to increase awareness and knowledge about its etiopathogenesis and management.