1. Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder with severe pruritus and worldwide increasing prevalence (1, 2). Atopic dermatitis affects up to 20% of children and 1-3% of adults (3). Various factors such as genetic, immunological, and environmental factors including food and air allergens, anxiety and stress, hormonal factors, dust mites, and staphylococcal infections are thought to play roles in the pathogenesis of AD (4-6). Many therapeutic options including topical corticosteroids and immunomodulators, antihistamines and sometimes, systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and azathioprine might be used as the first line treatment for the management of AD. However, these options might not control severe disease or might associate with some serious side effects (7, 8).

Nowadays, various types of phototherapy with UVA including oral psoralen plus ultraviolet A (standard PUVA), topical psoralen plus ultraviolet A (bath PUVA), and UVA1 (340 - 400 nm) are used as promising treatments of the severe AD with less important side effects (7, 8). Phototherapy improves AD via several mechanisms. For instance, it causes immune suppression by inducing apoptosis and immunomodulatory cytokines and reducing Langerhans cells (7, 9). In addition, phototherapy might have a direct antimicrobial effect on Staphylococcus aureus (10). Since the first report concerning phototherapy was published in 1978, many studies have been performed regarding the effectiveness of phototherapy in the treatment of AD (7, 11-16). Some of them evaluated the efficacy of phototherapy or compared the effectiveness of various types of ultraviolet (13, 16, 17); however, various aspects of phototherapy should be evaluated by clinical trials and experimental studies.

Regarding the high prevalence of AD worldwide, especially in Iran, this study was designed to introduce alternative modalities to decrease corticosteroids side effects. Although there are several reports concerning oral psoralen UVA therapy in treating AD, studies regarding the efficacy of bath PUVA are limited. We aimed to evaluate the efficacy of bath PUVA in the treatment of severe and atopic dermatitis.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

At the beginning of this quasi - experimental study, we enrolled 28 patients including 16 females and 12 males with the severe or refractory AD. All of them were referred to Razi Hospital in 2011. Inclusion criteria were age > 10 years, definite clinical diagnosis of the AD by an expert dermatologist according to the Hanifin and Rajka criteria (18), referring to Razi Hospital within the last three months for chronicity, and repeated attacks of the AD and/or uncontrollable AD with first - line treatments.

Exclusion criteria were patients with other chronic diseases rather than AD such as asthma and allergic rhinitis, other diseases or psychological disorders that could affect patients’ follow - up, mild or short - course controllable AD with first - line treatments, lack of compliance, systemic immunosuppressive treatments such as corticosteroids, azathioprine, and cyclosporine, a history of using any topical steroids or immunomodulators within the past two weeks, ophthalmologic disorders, photosensitivity disorder, and history of skin cancer. Following the approval of the study protocol by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, 28 patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled. Aims and methods of this research were completely explained to each participant and written informed consent was obtained.

2.2. Phototherapy

For Bath PUVA, we diluted 50 mL of 8 - MOP (oral methoxsalen) in 100 L water to reach the concentration of 3.75 mg/L. Patients floated in this solution for 15 minutes and then, dried themselves and underwent phototherapy (14).

Phototherapy was carried out thrice a week for three months (13 weeks) in the phototherapy ward of Razi Hospital. UVA started with 0.7 J/cm2; every two sessions, 0.5 J/cm2 was added to reach a maximum 12 J/cm2 and maintained at this level until the end of the study. If any adverse event occurred, UVA was not increased until the improvement of the adverse effect. If moderate erythema or burn occurred, UVA was decreased until these side effects were resolved.

2.3. Patients Assessment

In the study period, a dermatologist visited patients in four sessions: before phototherapy, at the end of the first month, at the end of the second month, and at the end of the third month of phototherapy. In these visit sessions, the patients were examined completely and they were asked about itching and quality of sleep to determine their SCORAD score. The SCORAD score was defined in 1993 by the European task force on the AD; it is the abbreviation of scoring of atopic dermatitis. This sum score combines the extent of involved body surface (by the rule of nines), the severity of six clinical signs including erythema, infiltration, exudation, excoriation, lichenification, and dryness with the severity of itching and insomnia. The intensity items are graded as zero, one, two, and three representing absence, mild, moderate, and severe signs and symptoms, respectively. In addition, the mentioned subjective symptoms were graded as zero to 10 based on a visual analog scale (VAS) (16, 19, 20).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We used SPSS version 13 to analyze data. The quantitative data were presented as mean and standard deviation whereas the qualitative data were shown as frequency and percentage. For analyzing SCORAD scores changes trend during the three-month period, the repeated measurement method, which is a general linear model, was used with a 95% confidence interval. In this model, SCORAD was considered as the major variable and sex and age were considered as covariates.

3. Results

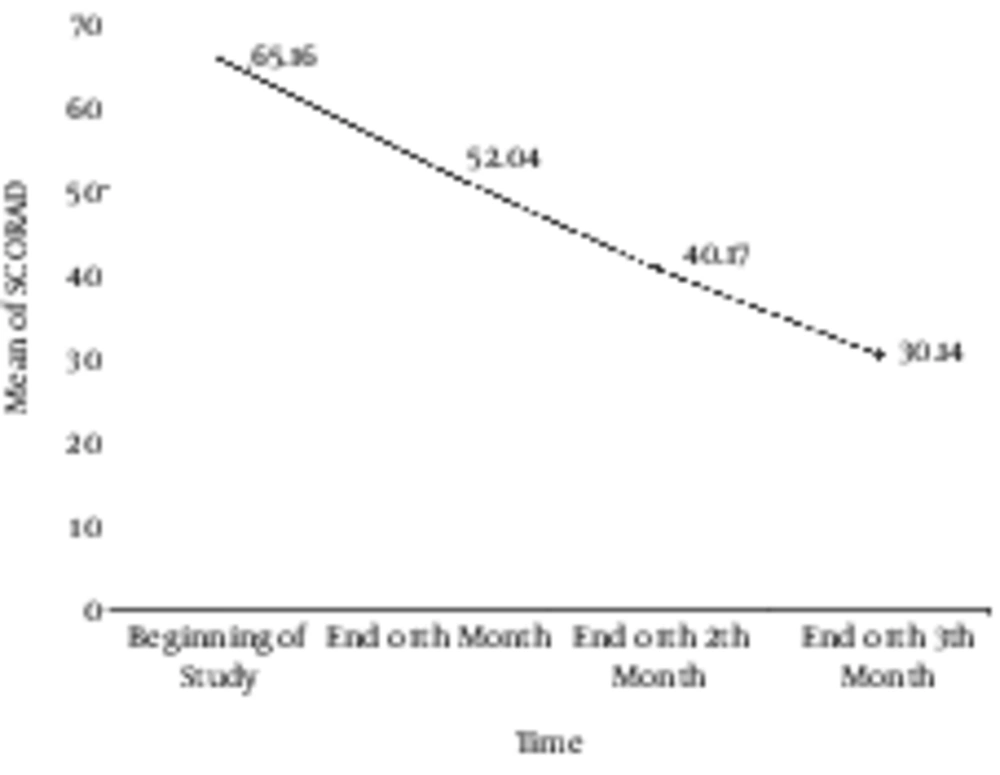

At the beginning of the study, 28 patients were enrolled; however, four patients left the study due to different reasons such as worsening clinical course, increasing itching, erythema, and hyperpigmentation in one patient, and immigration to another town in another one. In addition, two patients withdrew without any clear reasons. Finally, 24 patients remained in the study until the end of the three - month period. These 24 patients included 16 (66.7%) females and 8 (33.3%) males. The mean age of our patients was 29.39 ± 15.17 years ranging from ten to 65 years. A dermatologist visited the patients four times during the study to calculate their SCORAD. The mean of SCORAD in the four visits were 65.16 ± 11.18, 52.04 ± 14.95, 40.17 ± 15.90, and 30.14 ± 20.84 at the beginning of the study (SCORAD0), at the end of the first month (SCORAD1), at the end of the second month (SCORAD2), and at the end of the study (SCORAD3). The mean values of calculated SCORAD are shown in Figure 1. It indicates a significantly decreasing slope in the SCORAD values after the intervention. According to the multivariate test and the tests of within - subjects effects performed by Greenhouse - Geisser method with 95% confidence interval, we calculated a P value of less than 0.0001 and a power of one. These results show that bath PUVA had a significant effect on the decrease in the severity of AD. We evaluated confounding effects of age and sex on the results. Our findings showed that age and sex did not affect therapeutic outcomes of phototherapy; therefore, after omitting the effect of these two variables, we achieved a P value of 0.001 and a power of 0.948 with a 95% confidence interval.

| Complication | Results, N (%) |

|---|---|

| Hyperpigmentation | 20 (83.3) |

| Burning: Mild (stage 1) | 8 (33.3) |

| Burning: Moderate (stage 2) | 2 (8.3) |

| Itching exacerbation | 2 (8.3) |

| Xerosis | 14 (58.3) |

4. Discussion

Nowadays, phototherapy is a safe and effective therapeutic modality with less serious side effects for the severe and refractory - to - treatment AD (11, 16, 17, 21). Our quasi - experimental study showed that bath PUVA was effective and safe in the treatment of severe or refractory AD. The only limitation in using bath PUVA is its application to scalp and face eczema. Our results are supported by a variety of previous investigations on the efficacy of different types of phototherapy (8, 10-13, 15-17, 21). However, a few studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of bath PUVA in the AD so far (22). Therefore, we aimed to study bath PUVA rather than systemic PUVA that has some adverse effects due to the administration of oral psoralen. According to the present study, after 39 phototherapy sessions, SCORAD decreased significantly (P < 0.0001). In a similar study from Poland, a notable decrease occurred in AD signs after 30 phototherapy sessions (P < 0.001). In this study, 35 patients with severe AD underwent bath PUVA for 30 sessions with a maximum energy density of 12 J/cm2. Six patients left the study and worsening clinical signs occurred in three patients (21). In our study with smaller sample size, four patients left the study and no serious adverse effect was reported.

Many researchers proved the efficacy of systemic PUVA in the severe AD (11, 15, 22). For instance, Sheehan evaluated 53 children with the severe or refractory - to - treatment AD. After 18 sessions of systemic PUVA, 75% of them were treated without any sing (15). Moreover, some studies compared two different modalities of phototherapy (16, 22). For example, Der - Petrossian and colleagues compared the efficacy of 8 - methoxypsoralen bath PUVA versus narrow - band ultraviolet B phototherapy in 12 patients with the severe chronic AD. They found that the SCORAD score decreased by 65.7% in bath - PUVA and by 64.1% in narrow - band UVB. No serious adverse effect was observed at the end of the study (22). Although our study is not a controlled clinical trial, it showed a significant decreasing trend in SCORAD from 65.16 ± 11.18 at the beginning of the study to 30.14 ± 20.84 at the end of the study (P < 0.0001). In addition, reported adverse effects were not serious and the most common adverse events during the study were hyperpigmentation (83.3%) and xerosis (58.3%). Generally, based on some evidence, phototherapy adverse events include actinic keratosis, premature photoaging, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, hyperpigmentation, burning, nausea, headache, dizziness, urticaria, and cataract (14). Acute side effects in our study were burning, hyperpigmentation, xerosis, and exacerbation of itching.

Although our study was an interventional study, it had some limitations. It was quasi - experimental and we had no control group and randomization. In addition, our sample size was relatively small. For clear judgment about the efficacy of bath PUVA in patients with the AD, randomized controlled clinical trials with larger sample sizes are needed. In summary, the results of our study showed that bath PUVA is an effective and safe modality in the treatment of severe and/or refractory AD. Further randomized controlled clinical trials with a greater number of participants are recommended to confirm the efficacy of bath PUVA in the severe or refractory AD.