1. Background

The current COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, is considered the most severe worldwide public health problem of the last 100 years. As known, COVID-19 is an upper respiratory tract infection with a high transmission rate diagnosed through clinical evaluations and confirmed with laboratory testing or imaging (1). Measures to prevent COVID-19 transmission and control the outbreak mainly consist of social distancing and isolation, introduced in Brazil in mid-March of 2020, based on recommendations from national and international public health agencies and supported in the scientific literature (2).

People with spinal cord injury (SCI) are among those with greater susceptibility to COVID-19, as they may require caregiver support to help perform daily tasks (3), and previous pulmonary diseases can complicate the prognoses (4). In addition, people with SCI suffer reduced mobility and may also need to interrupt rehabilitation therapy, among other impairments. Therefore, the pandemic has highlighted the need to advocate for people with SCI and urgently provide educational tools for health workers on the best approaches for this group, as these workers may have little or no experience treating such individuals, and considering that patients with tetraplegia can be diagnosed with viral pneumonia without presenting a cough (5).

In light of the above, a survey was conducted in which SCI people were objectively asked if they believe the post-pandemic world will improve, stay the same, or get worse. In addition, the respondents were requested subjective questions to express their opinion on the theme to the researchers openly.

2. Objectives

The challenges associated with COVID-19 faced by citizens worldwide are more intense among people with SCI, and the neglect of people with disabilities in terms of access to health care, assistance, and support services is unacceptable and requires an inclusive disability response to the COVID-19 crisis (6). However, although some certainties about the virus have emerged, social distancing and COVID-19 impacts on people’s lives with SCI remain unknown, especially in Brazil. Despite uncertainties regarding the future, it is necessary to demonstrate the vulnerabilities perceived by SCI people and understand how they foresee their future. Therefore, this study aimed to understand the perceptions of SCI people in Brazil concerning the post-pandemic world.

3. Methods

This study was conducted using an online survey with a qualitative approach covering the entire Brazilian territory. Data were collected using the Survey Monkey® platform with an online questionnaire composed of 20 closed-ended and three open-ended questions, developed and validated by a group of nurses experienced in the rehabilitation of SCI people (available at https://surveymonkey.com/r/forpapers). Between May and June 2020, the questionnaire was sent to 1,300 volunteers diagnosed with SCI registered on the database of the research center linked to the University of São Paulo. Participants who did not complete the questionnaire were excluded, and those who completed the questionnaire were included, resulting in a sample of 204 participants. Informed consent, which was a requirement for completing the survey, was obtained from each patient included in the study.

In this research, only sociodemographic data and open-ended responses were considered. The sociodemographic data were subjected to descriptive analysis using absolute frequency, mean, median, percentage, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum. The means were followed by the standard deviation and the medians by the interquartile range. The open-ended responses were analyzed according to Bardin (7) for a more profound understanding of the data. This stage was immersed in the philosophical bases of Axel Honneth (8) on the Theory of recognition and ernst bloch (9) on the principle of hope.

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected in a prior approval by the institution’s human research committee, the Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Paulo, under the CAAE protocol 07355319.9. 0000.5393.

4. Results

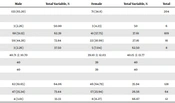

Most of the 204 study participants were male (65.19%), aged between 18 and 62, with a mean age of 40.71 years (SD = 10.70). The type of lesions included paraplegia (62.74%), tetraplegia (31.37%), and myelomeningocele (5.88%). The participants came from many regions of Brazil, especially the southeast (61.27%). Table 1 shows the characterization of the participants, and Table 2 shows the study participants according to gender, age, and injury level.

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 133 (65.19) |

| Female | 71 (34.80) |

| Origin | |

| Southeast | 125 (61.27) |

| South | 37 (18.13) |

| Northeast | 22 (10.78) |

| Central-West | 13 (6.37) |

| North | 07 (3.43) |

| Education | |

| Elementary school | 78 (12.6) |

| High school | 232 (37.5) |

| University | 306 (49.5) |

| SCI type | |

| Paraplegia | 128 (62.74) |

| Tetraplegia | 64 (31.37) |

| Myelomeningocele | 12 (5.88) |

| Total | 204 (100.0) |

Abbreviation: SCI, spinal cord injury.

| Male | Total Variable, % | Female | Total Variable, % | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 133 (65.20) | 71 (34.8) | 204 | ||

| Age | |||||

| > 20 | 3 (2.26) | 50.00 | 3 (4.23) | 50 | 6 |

| 21 - 40 | 68 (51.13) | 62.39 | 41 (57.75) | 37.61 | 109 |

| 41 - 60 | 59 (44.36) | 72.84 | 22 (30.99) | 27.16 | 81 |

| < 61 | 3 (2.26) | 37.50 | 5 (7.04) | 62.50 | 8 |

| Mean ± SD | 40.71 ± 10.70 | 39.10 ± 12.03 | 40.15 ± 13.77 | ||

| Mode | 40 | 39 | 40 | ||

| Median | 40 | 39 | 40 | ||

| Level spinal cord injury | |||||

| Paraplegia | 82 (61.65) | 64.06 | 46 (64.79) | 35.94 | 128 |

| Tetraplegia | 47 (35.34) | 73.44 | 17 (23.94) | 26.56 | 64 |

| Myelomeningocele | 4 (3.01) | 33.33 | 8 (11.27) | 66.67 | 12 |

aValues are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

When asked, “what is your perception of the post-pandemic world that we will live in?” the participants freely discussed their interpretations and reflections. The complexity of this type of analysis lies in understanding the inferences of themes or words and not in the frequency of their appearance in each individual communication. Therefore, to facilitate analysis in the qualitative study, the following four stages were defined: (A) Organization of the analysis; (B) coding; (C) categorization; and (D) treatment, inference, and interpretation of results (7). This analytical strategy gave rise to two central themes that will be analyzed in this study: “It will be the same or worse” and “there is still hope”.

4.1. Theme 1: It Will be the Same or Worse

Most participants (141 individuals, 69.11%) reported that the future in the post-pandemic world would be the same or worse given their perception of a materialistic and egocentric society. These individuals considered that issues such as economy, politics, and ideology would always be more important than the active and loving concern for others. Moreover, they reported that the pandemic would exacerbate this selfish perspective of people by directly and indirectly influencing market relations and, subsequently, causing an increase in poverty and violence.

The participants expressed insecurity about the future concerning the political inconsistencies they are currently experiencing, with poor administration and corruption strongly contributing to this insecurity. In addition, the participants mentioned that there is a lack of harmony in the relationship between human beings and the planet, with prioritization of financial profit and a lack of respect for the collective. These perspectives can be observed in the following excerpts: The economy is collapsing because of Coronavirus. This leads to numerous social problems that worsen the world (P. 13).

When all this is over, business people will want to make up for the delay, and pollution will get worse (P. 18).

The participants also reinforced that conflict between people is part of human nature, revealing the perception that there will be no significant societal changes. This perspective that humans are essentially self-centered and unchanging supports the perception that people will not be different after the pandemic and will soon forget the experience.

Our civilization has often gone through extreme situations and keeps repeating the pattern of behavior. When you return to normality, everything is forgotten (P. 43).

People do not respect social distancing and believe that personal desires are more significant than the health of an entire society (P. 61).

For the participants, another reason for this perspective is that they are already socially isolated due to SCI and not due to the pandemic:

Social isolation is already a reality for anyone with SCI, regardless of the pandemic. We live in a society that is exclusionary, unsupportive, and inaccessible to most of us (P. 85).

The vast majority of people with disabilities already live in never-ending social isolation caused by the lack of accessibility (P. 109).

The statements also revealed the mental impact of social distancing and isolation for people with SCI. Distancing is understood by the participants as the restriction of mobility, while social isolation is considered the impossibility of interacting with others. The participants reported that life has been mentally distressing, whereas difficulties of family adjustments, lack of access to treatments and rehabilitation, insecurity and fear concerning the future, awareness of the risk of transmission, and the political and economic consequences enhanced emotional fragility during the pandemic.

The suicide rate of the disabled is very high, and I do not see health policies concerned with this prevalence (P. 28).

I started having anxiety attacks again, and insomnia and my symptoms of spasticity increased due to the lack of physical therapy and physical activities (P. 87).

4.2. Theme 2: There Is Still Hope

Some participants (63 individuals, 30.88%) reported optimism in the situation they were experiencing. Even with the high numbers of those infected with and killed by COVID-19 in Brazil, people believe in a more supportive post-pandemic world. They believe in reconstructing values based on more respectful and trusting relationships through technology, reflection, and dialogue. Another factor possibly influential on humanity’s solidarity after the pandemic is that of the divine lesson: understanding the expression of divinity as a way of improving human existence and giving meaning to life.

The pandemic is an awakening to the existence of God because He shows us that we have to overcome material attachment (P. 21).

People, regardless of social class, are becoming more sensitive to others. Many are changing how they think and consume; they share more and act more sustainably (P. 100).

The present moment calls everyone to reflect on our reality. I suppose that has positive effects on humanity (P. 118).

The optimism of these participants also reveals opportunities to reflect on the world situation and rethink how to perform daily activities. Staying at home can be an opportunity to explore inter-family relationships and leisure activities. The pandemic has fostered a scientific evolution that makes the population more aware of self-care measures, hygiene, and empathy in diversity, in addition to the dissemination of knowledge through online courses. The home has started to represent more than the shelter of the family nucleus and has gradually become the place of work, leisure, and reflection.

Before, everything was restricted because of my mobility; today, this restriction does not exist because I only need a cell phone or computer (P. 103).

Usually, new technologies emerge after crises and scientific knowledge advances (P. 104).

I believe that the pandemic has been a time for humanity to rethink its very existence (P. 105).

People who believe in changing the planet for the better, with new meaning for priorities and behavioral changes, idealize this moment of humanity as a possibility to break with the biomedical model of disability. However, the participants believe it is also time to rethink the social model of disability, as it seems insufficient in the eyes of those living with the condition. The participants report that the moment we live is a time to rethink society’s behavior.

It is time to overcome the biomedical model of disability and reassess our social model. Everything must be reviewed. There is no concept or certainty that should not be reframed in this current moment in which we live (P. 110).

5. Discussion

The results showed a contradictory parallel between the participants with a pessimistic and hopeless perspective, who reported that the world would be the same or worse, and the participants who say that there is still hope and optimistically believe in a more supportive post-pandemic world.

Some statements confirm this pessimistic view of human nature with adverse reports regarding the present reality. Humans have lived for thousands of years and remain unsympathetic to the diversity of their own species. The construction of social values based on individualistic relationships restricts collective elaboration, resulting in the valuation of money and the devaluation of life. Furthermore, during the global crisis itself, people disregarded guidelines from international health organizations and overlooked the magnitude of a social, political, economic, and ideological pandemic.

The pessimistic perspective of Brazilians with SCI regarding society is based on the discourse of the egocentric and disrespectful nature of humanity. The participants mentioned the construction of human history as relentless and unchangeable, insofar as disrespect and immoral relationships are the foundations of civilization. For example, the invisibility of people with disabilities in Brazil is not new. However, the pandemic crisis has revealed how the transversal policies of education, health, social assistance, and accessibility are ineffective in Brazil and do not effectively communicate with each other (10).

Another factor that feeds the hopelessness of future improvements in humanity after the pandemic stems from the ideological crossroads between the economy and modern life. This mismatch is justified by the capitalist structure that fosters the value of technology and control over life. Thus, the COVID-19 crisis highlights this contradiction, with greater competitiveness in search of profit, based on pharmaceutical incorporations, the guidelines of political authority, and the cult of fear (11).

The participants believe that the daily life of people with disabilities in Brazil is one of disrespect, neglect, and isolation. This perspective of reality is the basis for the future of the world itself, as these people routinely experience the repercussions of a selfish society, incapable of reflecting on their own mistakes. Therefore, the routine of SCI people is impacted more strongly by lacking social accessibility than by the pandemic per se. The participants reported that they did not notice significant changes in their routine, as they already experienced social distancing daily because they are prevented from participating in society due to the challenges of accessibility in Brazil.

Therefore, some participants recognize the weaknesses experienced before the pandemic and thus believe there is no prospect of improvement for the future. These reports are based on the daily experiences of individuals with SCI in Brazil, who already live with social restrictions resulting from inaccessibility and the neglect of public policies (12). However, these participants reinforced that increased vulnerability occurred during the pandemic, stating that immobility can cause late deformities, and limited resources for medical care can cause neurological deterioration.

In addition, the unpreparedness of health care institutions to receive individuals with SCI represents another challenge, further indicating there is much to be learned about the impact of COVID-19 on the community with SCI (13). Moreover, extensive social isolation measures increase the psychological suffering of the human collective. This distance caused by the ordered restrictions is experienced by humanity as the suppression of individual needs and, simultaneously, as a gap in the cultural and attitudinal experience (3). As such, social isolation, which was not new for people with disabilities, began impacting people’s daily lives with the addition of emotional suffering (14).

In contrast, amid the contradictions of human nature, some participants believe there is still hope for a better world after the pandemic. This optimistic and forward-looking notion emerges from the ideology of social justice based on relationships of love, trust, and solidarity that will be reframed after the experience of the world crisis. The study participants and the literature alike define the civilizational crisis as a process in recreating concepts of human dignity (15). Therefore, hope emerges as the possibility to feedback this anguish from past reality and build a future based on relations of law and social conscience (16).

People see possibilities among difficulties, and this hope is founded on the creative impetus of people, who can then find ways to reinvent their own existence and keep trying. For this reason, optimistic people with SCI do not disregard the facts that hinder their confrontations in the face of the pandemic; instead, they recognize the obstacles as social expressions of transformation (16).

The hope of people with SCI helps make fundamental changes in their daily lives; moreover, this driving force is an effective coping strategy for establishing and achieving goals (16). Recognizing the human priority of reflecting on the historical trajectory and constructing new concepts also fosters more dignified relationships based on trust, respect, and social esteem. Recognition is a struggle, and, for this reason, the participant’s statements may seem pessimistic when, in fact, we are all in an eternal conflict to achieve reciprocal relationships. Therefore, this study reveals much more than the idealization of a world after the pandemic, as it enables the possible destruction of failed praxis as a springboard for an emancipated society (17).

The online survey revealed the processes people with SCI experience while questioning their perceptions of the future based on historical and social characteristics. The data showed that human nature is revealed through the process of struggle for recognition, founded on relations of disrespect to the intersubjective integrity of human identity and crossed by the relentless potential for individual and collective hope. Therefore, the future transformation of the world depends on present changes in human relations based on recognition, through dimensions of love, law, and solidarity as the pillars for the improvement of social awareness and good living.

Given the COVID-19 pandemic experienced in 2020, new research is needed to resolve the concerns identified in this study and standardize the best practice protocols for rehabilitation and health promotion of people with SCI, considering their emotional aspects. The limits of this research involve the non-participation of Brazilians with SCI who did not have internet access or a smartphone. In this regard, we also recognize the lack of accessibility of our research to all Brazilians with SCI.

5.1. Limitations

The study limitations were due to the pandemic and the need to conduct the survey online, which prevented us from obtaining certain information, such as the participants’ ASIA classification.