1. Background

Studies have shown that important events in life can affect a person’s emotional performance, but some of these events do not necessarily have long-term destructive effects and vary between different people depending on the coping strategies employed. Studies have shown that patients with psychosomatic problems do not have adaptive coping strategies (1). Gastrointestinal diseases, such as peptic ulcer, are examples of psychosomatic diseases that largely lead to referral to hospitals (1). Peptic ulcer is referred to as mucosal lesions in the stomach, pylorus, duodenum, and esophagus. Peptic ulcer is a very common condition with a higher prevalence in men than in women (2). The most common symptom of peptic ulcer is the burning pain that can be felt anywhere above the sternum. Weight loss, anorexia, and blood in stool are the other common symptoms of this disease (3). Although this disease is not associated with a high mortality rate, it has many psychosocial, emotional, and economic consequences as it is highly prevalent (10 to 12%) (4). Small ulcers are responsible for about 45% to 60% of hospitalizations due to acute gastrointestinal bleeding in the world (5).

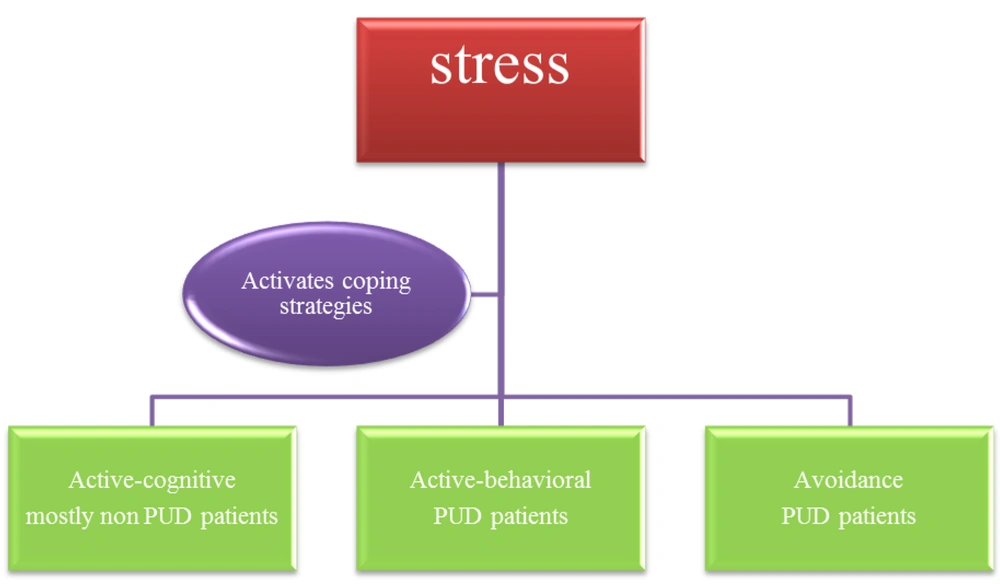

Preliminary studies on gastric ulcer have shown the role of psychological factors in the development of gastric ulcers (6, 7). Psychological stress has been reported to induce gastric acid secretion (8). Although stressful events have been considered major risk factors in bio-psychosocial research, many researchers believe that how people react to stressful events is more important than the stress itself (9). Recent research has shown that the type of the coping strategies used by a person affect not only his/her mental health but also his/her physical well-being (10). Coping strategies are the same behaviors and thoughts that are automatically used by people to deal with and minimize psychological damage. Stressful situations, if they are not managed properly, can cause psychological problems (11). There are three types of coping strategies: (1) cognitive strategy, which involves evaluating the event as stressful (e.g., comparing it to past situations), (2) active-behavioral coping strategies, which include tasks used by people to assess stressful situations, which sometimes makes situations worse (such as smoking, rather than solving the problem), and (3) avoidance coping strategy, referring to avoiding facing a problem (i.e., escaping from it, for example, sleeping more hours and trying not to think about it (12). Studies have shown that coping strategies are recognized as mediators between stress and illness (13) and play an important role in reducing anxiety, depression, and physical problems (14).

Peptic ulcers may develop in patients whose personalities and life experiences make them physically react to stressful stimuli. Some studies have identified active-behavioral and avoidance coping strategies as the most effective mediators of the disease-stress relationship (15). Some other studies suggested that stress-related illnesses such as peptic ulcer were more common in those who constantly use active-behavioral and avoidance coping strategies (16). On the other hand, employment of the cognitive coping strategy against stressful situations render events less stressful and soften reactions to its negative consequences (16). Figure 1 shows the relationship between coping strategies and stress in people with and without PUD, as mentioned in various studies (17-20).

Previous reports have often been focused on the role of biological agents, such as Helicobacter pylori, and used a clinical approach and pharmaceutical treatment to manage PUD (21). Meanwhile, the effect of socio-psychological variables on the occurrence and progression of peptic ulcers has not been investigated, especially in Iran. A few studies have examined the relationship between coping strategies in the face with stressful situations and PUD among Iranians (17-20), but most of these studies are correlational, and no interventional experiments have yet been done to assess the causative effects of these coping strategies. Therefore, this research investigated the efficacy of emotion regulation training on coping responses in attenuating the stress of life events in patients with PUD.

2. Objectives

Most previous studies have focused on the effectiveness of pharmaceutical therapeutic approaches in PUD patients, but in this study, we investigated the effectiveness of emotion regulation training on coping responses in attenuating the stress of life events in patients with PUD.

3. Methods

The present semi-experimental research was conducted in Tehran, Iran, between October and December 2021. Subjects were selected by the purposeful sampling method from March 2021 to June 2021. Eligible participants were randomly divided into the experimental and control groups. The experimental group started to receive emotion regulation training after two weeks of recruitment. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the training sessions were conducted online via WhatsApp or Skype, and face-to-face sessions were held only if the patient had referred to Ayatollah Taleghani Hospital to pursue his medical routines.

3.1. Instruments

3.1.1. Coping Style Scale (CSS)

This 19-item questionnaire was developed by Billings and Moos to assess how people respond to stressful events. When completing the questionnaire, respondents are asked to consider a crisis or stressful event they have just experienced and answer the questions according to how they coped with the event. The response options for each item were set on a Likert scale from never = 0 to always = 3. This questionnaire includes six sentences for cognitive coping strategy, six sentences for active-behavior strategy, and seven sentences for avoidance strategy. Its reliability was confirmed based on Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.78), and internal consistency values for its subscales ranged from 0.44 to 0.80. The content validity of the questionnaire was also obtained 0.88 (12). For its Persian version, Sayadi et al. obtained Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.73 (for the whole questionnaire), 0.77 (behavioral coping strategy), 0.83 (cognitive coping strategy), and 0.60 (avoidance coping strategy) (22).

3.1.2. Treatment Protocol

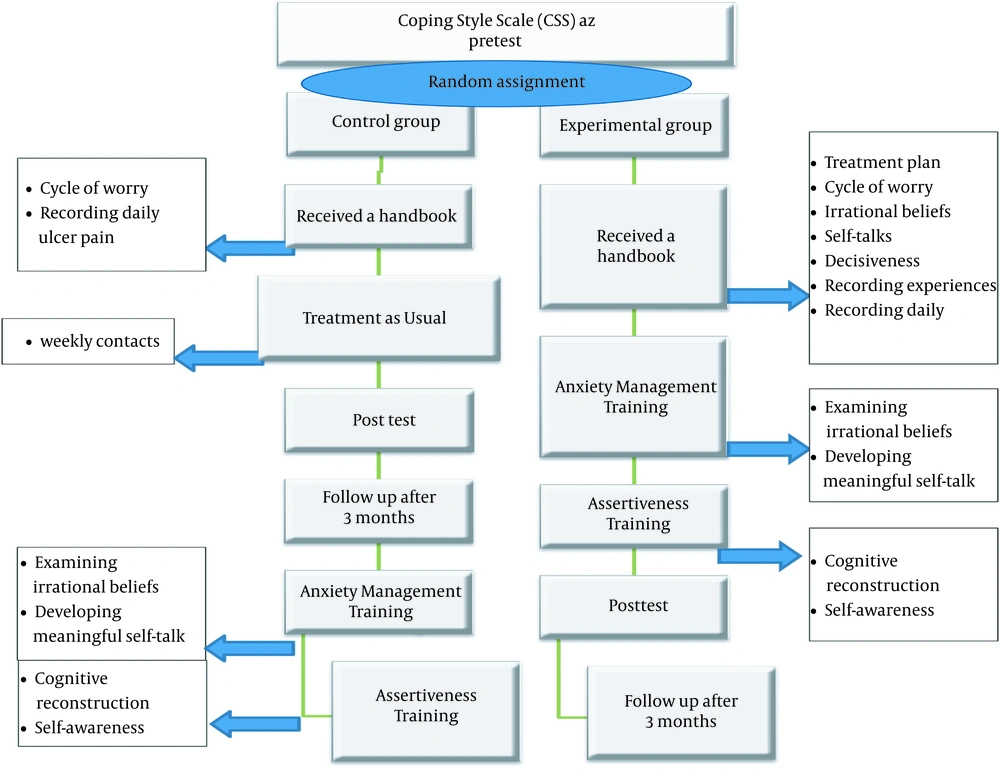

All stages of the study were performed in the Ayatollah Taleghani Hospital of Tehran. The training protocol included eight sessions delivered in eight consecutive weeks. This protocol was based on the Brooks treatment (1980), which was developed to treat duodenal ulcers (23). The experimental group was provided with a booklet that explained (A) the logic of the plan and the relationship between gastric ulcers, emotional control, and anxiety, (B) the cycle of anxiety and stomach pain using a graph, (C) the root causes of unnecessary anxiety, (D) positive self-talk and negative self-talk, and (E) assertiveness concepts. Furthermore, important experiences with newly learned behaviors were recorded, and charts were presented to record daily pain during the treatment period. The control group was provided with a booklet that explained the cycle of worry and contained graphs for recording daily ulcerative pain.

The emotional skills training program had eight sessions of 60 - 90 minutes and was performed individually for each patient in the experimental group. Four sessions of the program were dedicated to anxiety management training, and four other sessions focused on courage and assertiveness.

3.2. Anxiety Management Training

The program of anxiety management followed that presented by Richardson (1976) and included four sessions. During these sessions, the patients, with the help of the therapist, (A) examined their irrational beliefs causing them anxiousness (Ellis, 1973; Richardson, 1976) and negative self-talk in stressful situations and (B) developed and wrote personal beliefs and meaningful self-talks.

Training for Assertiveness: The second four sessions were according to the protocol presented by Lazarus in 1971. In these sessions, two factors were emphasized: (A) cognitive reconstruction focusing on correcting misconceptions about assertiveness and the consequences of non-judgment (with particular reference to ulcer-related problems) and (B) practicing assertive behaviors in every-day situations. Much of the courage training time was spent on the need to learn self-awareness. Chronic resentment with periodic anger outbursts and subsequent stressful guilt were particularly emphasized.

Usual treatment continued for the control group. In this group, contact were made with patients once a week for 15 minutes for eight weeks, but no major psychological interventions were performed. After the post-test and follow-up, the same interventions according to the protocol were performed for the control group as well. Figure 2 summarizes the procedures performed for the control and experimental groups.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee (code: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1400.519) and registered at Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (code: IRCT20201103049252N2).

3.4. Procedures

Ayatollah Taleghani Hospital is affiliated to the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and was selected purposefully to conduct the research. Inclusion criteria for participants were: (1) age between 18 and 50 years old and (2) peptic ulcer diagnosis based on endoscopic evidence and clinical symptoms approved by a gastroenterologist. Substance abuse, psychotic disorders, and suicidal ideation were among exclusion criteria. Also, one of the criteria for exclusion from the study was failure to participate in more than three therapy sessions, but all patients fully participated in the sessions, and no one was excluded from the study due to this reason.

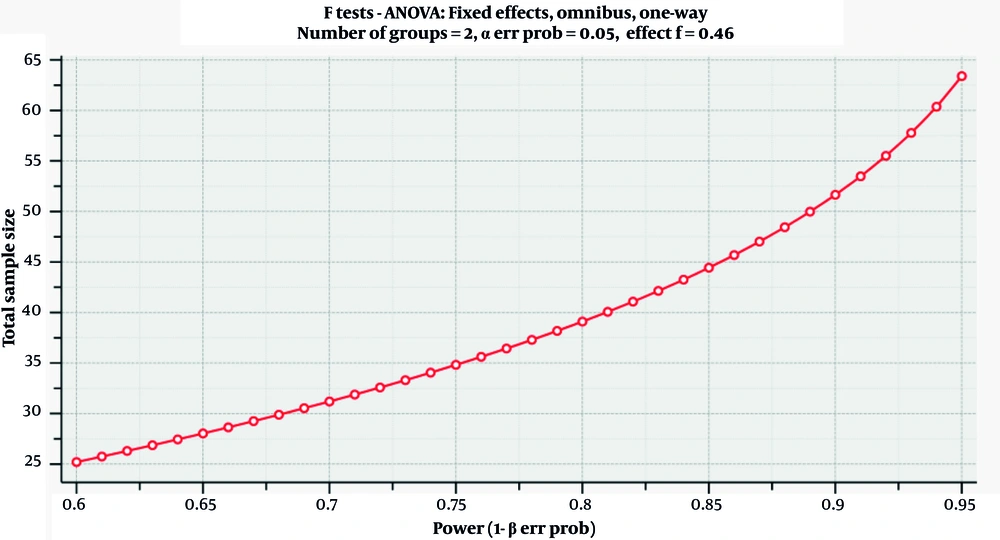

Using Gpower software for calculating the sample size, 40 people should have been included in the study group based on a type 1 error of 5%, frequency of occurrence of 77%, and accuracy of 0.1 (5). Regarding the possible dropout, 46 participants were included as participants in the research, all of whom completed the post-test with no withdrawal during the study. Figure 3 shows the formula used for calculating the sample size.

3.5. Data Analysis

The data required were collected before the intervention (i.e., baseline) and one week after the last training session. SPSS version 22.0 was used for data analysis, including descriptive characteristics, as well as inferential statistics (the ANCOVA test).

4. Results

The research findings are described in this section. Twenty-two and 24 patients were included in the experimental and control groups, respectively. In the experimental group, the minimum age was 18 years, and the maximum age was 40 years (mean = 32.54, SD = 2.21). Also, eight people were undergraduates; six people had diplomas; five people had bachelor’s degrees, and three people had master’s degrees. Regarding marriage status, 15 (68.2%) individuals in the experimental group were single, and seven (31.8%) were married. In the control group, minimum and maximum ages were 18 and 38 years, respectively (mean = 34.12, SD = 3.65). Also, nine people were undergraduates; eight individuals had diplomas; five people had bachelor’s degrees, and two people had master’s degrees. In this group, 14 (58.3%) individuals were single, and 10 (41.7%) were married. Table 1 shows the demographic information of the people participating in this research.

| Variables | Experimental Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 32.54 ± 2.21 | 34.12 ± 3.65 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 8 | 11 |

| Female | 14 | 13 |

| Education | ||

| Under diploma | 8 | 9 |

| Diploma | 6 | 8 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 5 | 5 |

| Master’s degree | 3 | 2 |

| Marriage status | ||

| Single | 15 | 14 |

| Married | 7 | 10 |

Demographic Information of Participants in the Experimental and Control Groups a

The normality of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Considering that P-values were higher than 0.05 for all variables, all of them were supposed to have normal distribution.

As shown in Table 2, the two groups had significantly different cognitive coping strategy posttest scores (P < 0.001), indicating that emotion regulation was effective in increasing cognitive coping strategies in PUD patients.

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive coping strategies | 1474.775 | 1 | 1474.775 | 559.467 | < 0.001 |

| Group memberships | 138.625 | 1 | 138.625 | 52.58 | < 0.001 |

Covariance Analysis of Cognitive Coping Strategies

According to Table 3, the two groups had a significant difference regarding the active behavioral coping strategy posttest score (P < 0.001), indicating the effectiveness of emotion regulation in reducing active behavioral coping strategies in PUD patients.

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active behavioral coping strategies | 156.874 | 1 | 156.874 | 3.25 | 0.07 |

| Group memberships | 5475.289 | 1 | 5475.289 | 113.69 | < 0.001 |

Covariance Analysis of Active Behavioral Coping Strategies

As shown in Table 4, the two groups had a significant difference in terms of the avoidance coping strategy posttest score (P < 0.01).

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoidance coping strategies | 1142.794 | 1 | 1142.794 | 9. 28 | 0.004 |

| Group memberships | 1732.196 | 1 | 1732.196 | 14.06 | 0.001 |

Covariance Analysis of Avoidance Coping Strategies

5. Discussion

This study showed that emotion regulation training could enhance cognitive coping strategies and reduce active behavioral and avoidance coping strategies. The findings of the present study were consistent with those of previous research. One study noted that stress coping styles employed by patients with gastrointestinal problems were significantly different compared to that used by healthy individuals (19). It was also reported that stress management program was effective in modulating psychological and physiologic stress reactions in patients with peptic ulcers (24).

Our study showed that emotion regulation training increased the use of cognitive coping strategies by patients with peptic ulcer symptoms. Researchers have shown that people who use problem-solving coping strategies have relatively adequate cognitive and dynamic skills to deal with the problem (25), enabling them to solve problems better and change stressful situations. After participating in the training sessions, PUD patients reported that they would try to analyze the stressful situation, plan to alleviate or eliminate the stressful situation, and think about the best way to control their problems. Therefore, the use of these techniques had made these people less likely to avoid problems and encouraged them to deal with them in a problem-oriented manner. Patients also reported that they did not have the power to reject irrational requests from others before treatment but were able to respond negatively after receiving assertiveness training.

Explaining this finding, it can be said that people with peptic ulcer symptoms are more inclined to forget their problems and try to reduce the stress caused by the problem by working and doing leisure activities rather than changing or solving the problem (20). These behaviors reduce stress in the short term, but because the problem remains unresolved, in the long term, these people become more vulnerable to stress, exaggerating stomach pain and causing peptic ulcers to recur (26). In the present study, during the training sessions, irrational beliefs were discussed to make people recognize and replace them with more rational beliefs. Individual self-talk were reviewed during the sessions and replaced with healthier self-talk. A combination of all of these techniques would allow the person to deal with stressful events in a thoughtful and healthier manner rather than neglecting them.

Another finding of this study showed that emotion regulation was effective in reducing avoidance coping strategies. Researchers have shown that patients with gastrointestinal symptoms tend to use an inflexible coping strategy when facing stressful situations (27). This coping style allows their problems to remain unchanged regardless of their ability to change. In this regard, the results of another study showed that avoiding the stressor (by ignoring the condition, using sedatives, or smoking) was more prevalent among patients with peptic ulcers than healthy people (17). One study found that severe gastrointestinal illnesses were associated with avoidance coping strategies characterized by poor adaptation and escaping from rather than engaging in stressful situations. In the long run, this strategy hinders psychological adjustment and increases feeling of helplessness and depression (28). Instead of avoiding stressful situations, cognitive reconstruction helps people endure the anxiety caused by these events and think of a solution for them (29). In this study, our results supported this notion as these techniques attenuated avoidance coping strategies.

More comprehensive research and longer following up patients in terms of psychological problems can provide better perspectives in future studies to clarify the role of psychological factors and psychotherapy in the management of patients with PUD.

5.1. Limitations

People suffering from peptic ulcers considered their illness a physical problem and did not cooperate much with psychological treatment. For this reason, among the many people who were interviewed, only a few were willing to participate in the treatment. On the other hand, this intervention was performed amid the COVID-19 pandemic when in-person referrals harbored the risk of disease transmission, so the treatment sessions were conducted online via video calls, which may not be as effective as face-to-face treatments.

5.2. Conclusions

Considering the positive effects of emotion regulation training in patients with peptic ulcers, it is concluded that this strategy is used to augment cognitive coping strategies in these patients. Such interventions, along with drug therapies, can help better manage these patients.