1. Context

Aging is a complex phenomenon. Numerous theories have been proposed to explain the concept of aging, but none has been able to clarify the mechanism and complexity of the aging process. Different classifications have also been developed for old age which is mostly defined as the calendar age of 65 years or older (1).

The significant and rapid growth of the aging in the world is one of the most important phenomena of the current century. The elderly population worldwide has been growing approximately 3% annually (2) and, according to the estimates by Rudnicka et al., the population aged over 60 will reach to 22% by 2050 (3). Furthermore, a high percentage of the population pyramid in developing countries falls within the age group of 15 - 64 years, which will lead to an increase in the elderly population during the following decades (4).

It is expected that the elderly population will grow faster in Iran than in other countries from 2040. According to the general population and housing census of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 2011, elderly people accounted for nearly 2.8% of Iran's population; this number increased to about 9.28% in 2016, and it was estimated that this statistic would increase in the next 25 years (5). With a deeper insight into population growth, aging is perceived as an enormous challenge for countries regarding the provision of safety and welfare for their elderly population (4).

Since aging has various marked effects on life, the major topic of "healthy and successful aging" takes on added importance. It is defined as creating empowerment opportunities to improve health, to participate as much as possible in order for enjoying a higher quality of life, and to achieve maximum physical, cognitive, and psychosocial health during a person's lifetime (WHO 2005) (3).

Healthy and successful aging is not separable from older adults attaining meaningful and productive live courses in order to contribute to society (3). Urban lifestyle changes including social networks, demographic conditions, socio-economic and health status may decrease the satisfaction and quality of life in the elderly. However, participation in social activities and activities related to leisure can resolve the given issues for the elders (4, 6). Social participation is now the focus of many research studies in gerontology, and is included in many conceptual models of successful aging (3).

According to Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (4th Edition) (OTPF-4), the social participation is defined as "activities that involve social interaction with family, friends, peers, and other members of society resulting in mutual social interaction” (6). The subject of social participation and leisure have a reciprocal connection in lives of older adults (3). Leisure is also defined by OTPF-4 as "an activity that is motivated internally and intrinsically, is not compulsory, and is performed in a free time which is not dedicated to other occupations and activities" (7).

The main component of WHO concerning globe aging can be followed via older adults’ informal assistance and formal community engagement (represented as social participation), and can be operationalized through social and leisure activities (8).

Since participation of community-dwelling older adults in social and leisure activities increases the quality of life, mental and physical health, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and sense of belonging to community, as well as decreases the risk of mortality and depression rates (9), the current study aimed to investigate the factors affecting the participation of community-dwelling older adults in activities associated with leisure and social participation.

2. Methods

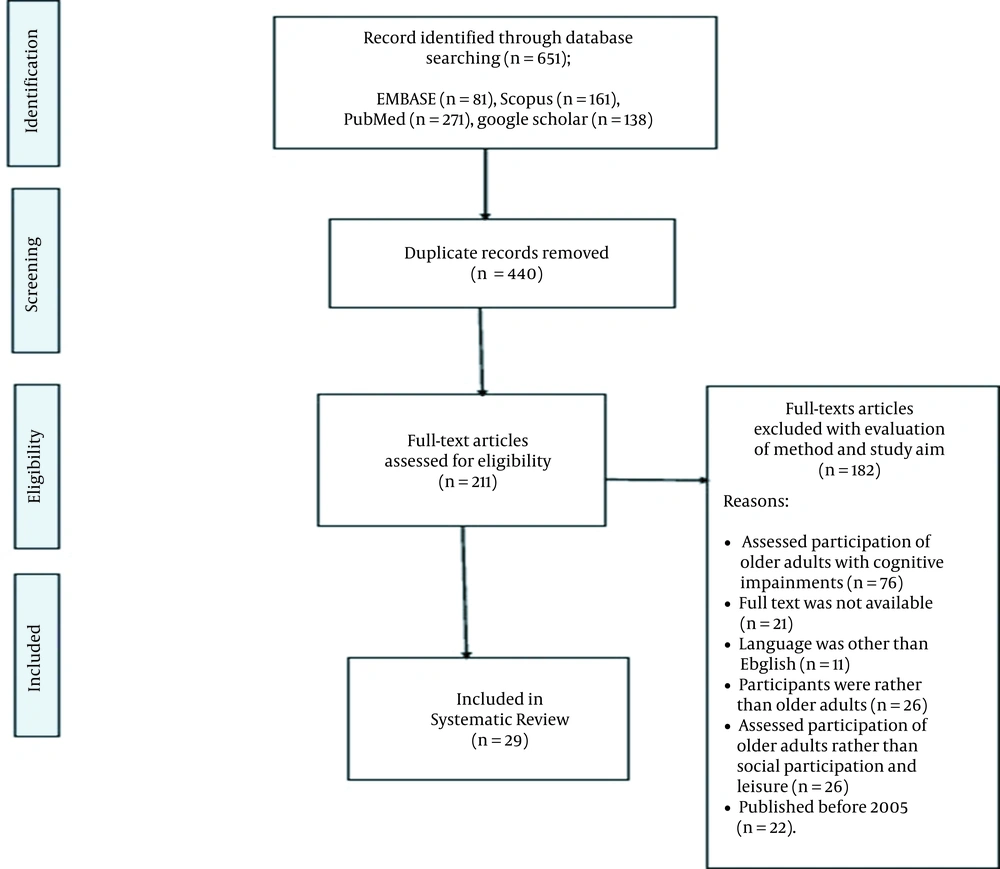

In this study, the systematic evidence-based review method was adopted (10). To report the review results, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) were used (11). Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, and EMBASE databases were searched using the following keywords: Aging, Ageing, Older, Elder, Senior, Age, Social Participation, Participation, Leisure, Activity, Quality of Life, Leisure Activities, Older Adult, Frail, and Engagement. "AND" and "OR" as the main Boolean operators were also used to combine searched terms (e.g., "Aging AND Leisure").

3. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: Published articles in a peer-reviewed journals, the topics associated with participation of community-dwelling older adults in activities related to social participation and leisure, English language articles published from 2005 to 2022 in one of the I (systematic review, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trials), II (groups, non-randomized studies [e.g., cohort, case control]), III (one group, non-randomized [e.g., before and after, pretest and posttest]), and IV (descriptive studies including analysis of outcomes [single subject design, case control]) of American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) levels of evidence (12). As for the exclusion criteria, those articles at level V (case report and expert opinion including narrative literature reviews and consensus statements), as well as theses, presentations, and conference papers, were excluded from our study.

In this study, the first author and an independent researcher searched and reviewed the articles based on the title and abstract between April 9, 2022, and May 21, 2022, individually, and then the full text was screened carefully by them if the article met eligible criteria. A total of 651 articles were identified by them, but only 211 articles remained after removing the duplicate articles. The remaining studies were re-screened by two authors (i.e., first and second authors) according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reasons for excluding the articles were as follows: Assessing participation of older adults with different cognitive impairments (n = 76), unavailability of the full text (n = 21), articles written in non-English language (n = 11), participation of individuals other than older adults (n = 26), assessing participation of older adults rather than social participation and leisure (n = 26), and publications before 2005 (n = 22). Finally, 29 articles determined eligible by both authors (the rate of agreement = 92%) were included in our study (Figure 1). Any opposition were resolved through discussion with the third author.

4. Data Extraction

Data on the authors, title, type of study, sample size (No./ age, mean ± SD/ (male/female), assessment tool, areas (leisure or social participation), related factors, and relevant results (Table 1) were extracted from the selected articles by first and third author.

| The Data Extracted from 29 Studies/Authors | Title | Type of Study | Sample Size, No./ Age, Mean ± SD/ (Male/Female) | Assessment Tool | Areas (Leisure or Social Participation) | Results | Associated Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giles et al. (13) | Social networks and memory over 15 years of follow-up in a cohort of older Australian | Cohort study (longitudinal) | N = 706/ Age = 78.6 ± 5.7/ (476/230) | Social networks Measure | Social participation | The participants having more friends and more social connections had a stronger memory with a higher score compared to the elderly having less social connections with their friends. | Memory (episodic), place of residency, marital status, disability, age, social networks (family, children, friends), personal contact, phone contact |

| Gottlieb & Gillespie (14) | Volunteerism, health, and civic engagement among older adults | Cohort | ? | - | Social participation | The elderly participating in voluntary work enjoyed higher level of health and well-being compared to other elderly, so there was a need to plan to encourage the elderly to participate in voluntary work. | Disability (mobility restriction), illness, education, socioeconomic, condition, immigration |

| Parkinson et al. (15) | Volunteering and older women: Psychosocial and health predictors of participation | Cohort (longitudinal study) | N = 1744/ Age = 70 - 75 ± ?/ (0/1744) | Duke social support index (DSSI) | Social participation | All women active in voluntary work enjoyed higher level of social support and higher quality of life compared to other elderly women. | Place of residency, birth country, language, economic status, insurance, education, disability (physical restriction) |

| Olesen & Berry (16) | Community participation and mental health during retirement in community sample of Australians | Cohort | N = 633/ Age > 45/ (322/311) | Types of community participation (ACPQ) | Social participation | In Australia, retirees had less desire to participate in social work and activities compared to working people, and one of the most important factors was the transition age to the retirement stage in this country. | Sex, economic status, education level, residency |

| Rezaeipandari et al. (17) | Social participation and loneliness among older adults in Yazd, Iran | Cross-sectional study | N = 200/ Age > 60/ (64/136) | Social participation activities | social participation | In Yazd, the presence of comorbidities, participation in social activities, and prevailing obstacles to social participation activities were predictors of isolation in the elderly. | Disability (visual, auditory), illness (pain in joints, osteoporosis, orthostatic hypotension, obesity, oral/dental problems), sleep disorder |

| Coyle & Dugan (18) | Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults | Cohort (longitudinal study) | N = 11,825/ Age = 67.67 ± 10.312/ (4348/6977) | Hughes 3-Item Loneliness Scale | Social participation | In the present study, loneliness was not associated with social isolation. Loneliness was more associated with mental health disorder, and isolation was more associated with one's fair/poor health. | Physical and mental health, age, economic status, education, habit (smoking, drinking), number of children,, family, friendship, relationships |

| Dahan-Oliel et al. (19) | Transportation use in community-dwelling older adults: Association with participation and leisure activities | Cross-sectional study | N = 90/ Age > 65; 76.3 ± 7.7/ (32/58) | Craig handicap assessment and reporting technique (CHART) & Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire (NLQ). | Social participation & Leisure | Elderly people using public transportation had greater mobility and, as a result, active social participation compared to other elderly people. | Gender, education, economic status, physical, condition |

| Dicken et al. (20) | An evaluation of the effectiveness of a community mentoring service for socially isolated older people: A controlled trial | Prospective controlled trial study | N = 395 (control group: 195, intervention roup: 200)/ Age = 71.8 ± 12.2 (intervention group); 69.8 ± 11.6 (control group/ (62/138: Intervention group); (76/115: Control group) | Social Activity, Social Support and Morbidities Questionnaires | Social participation | Social counseling was not effective in improving the health/social activity and reducing depression of the elderly; these interventions were community-based, which could prevent their social isolation by promoting the social participation of the elderly. | Marital status, place residency or accommodation type, economic status |

| Bertelli-Costa & Neri (21) | Life satisfaction & participation among community-dwelling older adults: Data from the FIBRA study | Cross-sectional study (part of FIBRA study) | N = 2344/ Age > 65; 72.3 ± 5.5/ (806/1538) | Social activity index | Social participation & Leisure | Good physical activity associated with leisure led to life satisfaction in the elderly and life satisfaction, in turn, increased the social participation of the elderly. | Economic status, habit (physical exercise) |

| Gale et al. (22) | Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for the progression of frailty | Longitudinal study | N = 2,817/ Age ≥ 60; 69.3 ± 6.9/ (1213/1,604) | Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale and Social Isolation | Social participation & Leisure | Social isolation did not cause physical weakness in the elderly, but increased the risk of contracting physical diseases and subsequent physical weakness among the elderly, especially among the elderly men. | Contact with family and friends, participation in social organization |

| Merz & Huxhold (23) | Well-being depends on social relationship characteristics: Comparing different types and providers of support to older adults | Cohort study | N = 1146/ Age > 65; 75.16 ± 5.24/ (583/563) | Deutscher Alterssurvey (German Ageing Survey; DEAS) | Social participation & Leisure | No relationship was found between social well-being and social participation; other factors were more associated with the level of social participation of the elderly. | Age, sex, insurance, relationships, kin and non-kin support, subjective health, functional health, marital status |

| Okura et al. (24) | The relationship of community activities with cognitive impairment and depressive mood independent of mobility disorder in Japanese older adults | Cross-sectional study | N = 5,076/ Age = 75.9 ± ?/ (2113/2963) | The Kihon checklist | Social participation & Leisure | Participation in social activities significantly reduced the cognitive disorders/depression in the elderly and promoted the participation in voluntary work, daily shopping, communication with friends and family, and leisure activities. | Physical fitness, memory, mood |

| Santini et al. (25) | Social relationships, loneliness, and mental health among older men and women in Ireland: A prospective community-based study | Longitudinal study (A prospective community-based study) | N = 6105/ Age > 50/ (2779/3326) | Berkman-Syme social network index (SNI) and University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale | Social participation & Leisure | Spouse support in the elderly and more effective social communication with friends and children reduced the symptoms of depression in elderly women and, subsequently, increased their social participation. | Support/strain from spouse/children from other family, social network index, |

| Schnittger et al. (26) | Psychological distress as a key component of psychosocial functioning in community-dwelling older people | Cross-sectional observational study | N = 579/ Age = 72.53 ± 7.14/ (179/400) | Practitioner Assessment of Network Type, and Lubben Social Network Scale | Social participation | The presence of psychotic disorders in the elderly decreased the psychosocial functioning in the elderly and, therefore, decreased the social communication and social participation in the elderly. | Age, gender, balance, educational, marital status, friends’ frailty, |

| Vozikaki et al. (27) | Activity participation and well-being among European adults aged 65 years and older | Cross-sectional (Cross-European Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE, http://www.share-project.org) | N = 7025/ Age > 65 | Activity Participation Questionnaire | Social participation & leisure | Social participation in old age was important for the well-being of the elderly, and increased the public health and social health of people. | Age, gender, educational, economic status, marital status, productive activity participation (in previous month), social activity participation (in previous month) |

| Wang et al. (28) | Associations between social networks, social contacts, and cognitive function among Chinese nonagenarians-centenarians | Cross-sectional study (data were from subjects of the Project of Longevity and Ageing in Dujiangyan, China.) | N = 870/ Age = 93.47 ± ?/ (284/586) | Social Networks Questionnaire, and Social Contacts Questionnaire | Social participation | Being single, having poor relationships with friends, and having poor social relationships with others were associated with an increased risk of dementia and cognitive problems in the elderly. | Age, gender, education, economic status, number of children/close friends, marital status, place of residency, social contact |

| Czaja et al. (29) | Improving social support for older adults through technology: Findings from the PRISM randomized controlled trial | Randomized, controlled trial | N = 300 (Control group: 150, intervention roup:150)/ Age = 76.15 ± 7.4/ (66/234) | Friendship Scale, Loneliness Scale, interpersonal support evaluation list, and Lubben social network index | Social participation | Participation in social activities improved social well-being in the elderly; all interventions made to improve the social participation of the elderly (e.g., working with technology, computers) increased self-efficacy and sense of sufficiency in the elderly. | Age, education, economic status, social support, marital status, place of residency, social functioning |

| Jansen-Kosterink et al. (30) | The first evaluation of a mobile application to encourage social participation for community-dwelling older adults | Cross-sectional study | N = 91/ Age = 73.4 ± 7.8/ (50/41) | System Usability Scale (SUS), technology acceptance model (TAM), and the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (DJGLS) | Social participation | Using smart programs in the cellphones by the elderly increased the life satisfaction and quality of life in the elderly; majority of the elderly were inclined to keep using such smart programs in their cellphones. | Age, education, place of residency, attitudes toward technology, marital status |

| Matz-Costa et al. (31) | Parallel, two-arm pilot randomized controlled trial | Randomized trial | N = 30 (control group: 15, intervention roup:15)/ Age = 72.92 ± 6.65/ (8/24) | physical activity (PA), cognitive activity (CA), social interaction (SI), and personal meaning (PM) | Social participation | Improving the factors associated with social participation increased the well-being and quality of life in the elderly. | Cognitive ability |

| Neil-Sztramko et al. (32) | Impact of the AGE-ON tablet training program on social isolation, loneliness, and attitudes toward technology in older adults: Single-group pre-post study | single-group pre-post program | N = 32/ Age > 60; mean: 76.3/ (12/20) | 6 Likert Scale Questions & Questionnaire | Social participation | Using tablets and the teaching the elderly to use them increased their quality of life and improved their attitudes; however, it did not significantly affect the social isolation and social support of the elderly. | Age, education, marital status, place of residency, cognitive function |

| He et al. (33) | Social participation, willingness and quality of life: A population-based study among older adults in rural areas of China | Cross-sectional study | N = 2644/ Age > 60; 70.6 ± 15.5/ (1079/1565) | Social Participation Questionnaires, Willingness of Taking Part in Social Activities Questionnaire, HQOL, and Demographic Health-related and Environment Variables Questionnaire | Social participation | The rural elderly were less willing to participate in social activities and, consequently, had less quality of life related to health and social support; therefore, it was recommended that the policymakers should develop appropriate incentive programs to promote the participation of the elderly in social activities as much as possible. | Place of residency, education, marital status, social support |

| Marsh et al. (34) | Factors associated with social participation amongst elders in rural Sri Lanka: A cross-sectional mixed methods analysis | Cross-sectional study | N = 1028/ (485/543) | Outcome-Level of Social Participation, Quality of Life Instrument, and Sociodemographic Questionnaire | Social participation | Elderly people living in poor and isolated geographical areas had less social participation compared to other elderly people. | Economic status, place of residency |

| Vogelsang (35) | Older adult social participation and its relationship with health: Rural-urban difference | Longitudinal study (Wisconsin longitudinal study (WLS)) | N = 3,006/ Age = 71.2 ± 0.92/ (1389/1617) | Interview, self-rated health (SRH) | Social participation | Compared to the elderly living in the cities, the elderly from the villages were more passive in terms of social participation; even the type of activity and the place of their activity were different. | Meeting friends, physical activity, civic groups, community centers, charity or welfare organizations |

| Marken & Howard (36) | Grandparents raising grandchildren: The influence of a late-life transition on occupational engagement | Data analysis (descriptive statistics)/mixed method study | N = 10/ Age = 60 – 72/ (5/5) | SF-36v2 Health Survey, Activity Card Sort, Demographic Questionnaire, and Interview | Leisure & social participation | Raising and taking care of a grandchild as a social activity had a positive effect from the grandfathers’ viewpoint, and a negative effect from the grandmothers’ viewpoint, on mental and physical health. | Physical functioning, pain, general health, vitality, mental health |

| Luo et al. (37) | Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study | Cohort study | N = 2101/ Age > 50 | The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale, and Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) | Social participation, & Leisure | The presence of a sense of loneliness in the elderly increased the risk of elderly mortality, depressive symptoms, and functional limitations in the elderly. Therefore, attempts to improve the social participation of the elderly may have exerted a significant effect on the quality of life and social well-being of them. | Depressive symptoms, age, race, self-rated health, marital status, education, household asses, physical exercise |

| Lee et al. (38) | Leisure activity participation as a predictor of quality of life in Korean urban dwelling elderly | Cross-sectional study | N = 185/ Age = 69.53 ± 4.81/ (81/74) | Time Use Survey, Korean Version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment, Instrument-BREF: WHOQOL-BREF (2002), and participation time in leisure activities | Leisure & social participation | Participation in leisure activities was largely associated with the quality of life of the elderly, and among them, the type of participation in leisure activities was associated with the culture of the Korean people; culture was a relevant factor in this field. | Participation in outdoor activity, sports, using media (technology), religious |

| Momtaz et al. (39) | Social embeddedness as a mechanism for linking social cohesion to well-being among older adults: Moderating effect of gender | Cross-sectional study (national survey) | N = 1,880/ Age > 60; 69.79 ± 7.36/ (891/989) | Social cohesion, WHO well-being index (WHO-5), social embeddedness, Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS), and emotional support | Social participation | The social participation of the elderly was associated with their social well-being and social cohesion, and among them, this communication pattern was different in elderly men than in elderly women; the type of neighborhood residence also determined the amount and type of participation. | Social cohesion/support, emotional support |

| Chang et al. (40) | Social relationships, leisure activity, and health in older adults | Cohort study (Using data from the 2006 and 2010 waves of the nationally representative U.S. Health and Retirement Study) | N = 2,965/ Age ≥ 50/ (1476/1489) | Social relationships, Leisure Activities, Physical Health, Psychological Well-being Questionnaires | Leisure & social participation | Participation in leisure activities was considered as a mediator between social participation and social health in the elderly. In the meantime, the elderly more willing to participate in leisure activities participated in more social activities with more variety. | Age, race, education, psychological status, mental status, social support from family |

| Chan et al. (41) | Living arrangements, social networks and depressive symptoms among older men and women in Singapore | Cohort study social isolation, health and lifestyles survey (SIHLS) (2009) | N = 4489/ Age > 60; 69.3 ± 7.2/ (2078/2411) | 11-item CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression), Scale, Social Network and Social Activities Questionnaire | Social participation | Older adults living without a spouse reported more depressive symptoms and less social participation compared to older adults with a spouse and children. | Place of residency, social networks, age, race, education, chronic disease |

5. Results

Out of 29 articles, three articles were at evidence level I, 12 were at evidence level II, one was at evidence level III, and 13 were at evidence level IV. The social participation of the elderly was discussed in all 29 articles; however, the leisure activities of the elders, in addition to the social participation, was discussed in only 11 articles.

In the present study, factors associated with participation of community-dwelling older adults in activities related to leisure and social participation were found to fall into two categories of individual and environmental factors.

6. Factors Associated with Social Participation of Community-Dwelling Older Adults

6.1. Individual Factors

In the current study, the highest individual factor directly associated with the social participation of community-dwelling older adults was the level of education of the elderly, which was discussed in 14 studies (14-16, 18, 19, 26-30, 32, 33, 37, 40). On the other hand, the lowest factors were associated with religion (38), language (15), and sleep disorders (17) of the elderly. Other individual factors associated with social participation of community-dwelling older adults in the given studies in order of the highest to the lowest factor were: age (18, 23, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 37, 40-42), disability (e.g., mobility restriction, vision problems, audio problems, physical, mental and cognitive functions disorders, etc.) (13, 14, 17, 19, 24, 26, 31, 32, 36, 37, 40), marital status (13, 20, 23, 26-30, 32, 33), Illness (e.g., joints pain, osteoporosis, orthostatic hypotension, obesity, oral/ dental problems,…) (13-15, 17, 18, 23, 36, 37, 41) sex or gender (16, 19, 23, 26-28), and habitual behavior (e.g., smoking, drinking, physical exercise,…) (18, 21, 35, 37).

7. Environmental Factors

The highest environmental factors directly associated with social participation of community-dwelling older adults was the social networks/support (e.g., family, children, friends, organizations, etc.) of the elderly, which was discussed in 16 studies (13, 18, 23, 25-29, 33, 37-41). The lowest factors, on the other hand, were associated with the immigration (14) and birth country (15) of the elderly. Other environmental factors associated with social participation of community-dwelling older adults in the given studies in order of the highest to the lowest factor were: Place of residency (13, 15, 16, 20, 28-30, 32-34, 41), economic status (14-16, 18-21, 27, 29, 34), insurance (15, 23), and use of technology/media (30, 38).

8. Factors Associated with Leisure Activities of Community-Dwelling Older Adults

8.1. Individual Factors

In the current study, the highest individual factor directly associated with leisure activities of community-dwelling older adults was the disability (e.g., mobility restriction, vision problems, audio problems, physical, mental and cognitive functions disorders, etc.), which was discussed in five studies (19, 24, 36, 37, 40). The lowest factors, on the other hand, were associated with the religion (38) of the elderly. Other individual factors associated with leisure activities of community-dwelling older adults in the given studies in order of the highest to the lowest factor were: Level of education (19, 27, 37, 40), age (23, 27, 37, 40), sex or gender (19, 23, 27), Illness (e.g., joints pain, osteoporosis, orthostatic hypotension, obesity, oral/ dental problems, etc.) (23, 36, 37), marital status (23, 27, 37), habitual behaviors (smoking, drinking, physical exercise, etc.) (21, 37), and race (37, 40).

8.2. Environmental Factors

In the current study, the highest environmental factor directly associated with leisure activities of community-dwelling older adults was the social network (e.g., family, children, friends, organizations, etc.), which was discussed in six studies (22, 25, 27, 37, 38, 40). The lowest factors, on the other hand, were associated with Insurance (23) and Use of technology/media (38) by the elderly. Another environmental factor associated with leisure activities of community-dwelling older adults in the given studies was Economic status that was discussed in three studies (19, 21, 27).

The data extracted from 29 studies are shown in Table 1.

9. Discussion

The present study facilitated the understanding of the concepts of social and leisure participation of older adults and a successful aging process and addressed the question of how they promoted health outcomes and enabled communities to positively influence the aging process of the most vulnerable group of society (9).

According to a follow-up cohort study by Tabue Teguo et al., factors like feeling of loneliness and living alone were effective predictors of mortality rate in older adults (43). Therefore, it is essential to investigate the most important factors affecting the social and leisure participation of older adults in all types and to explore their activity engagement levels.

Social participation and leisure activities are positively associated with higher social welfare as well as with decreased rate of mortality and physical/mental complications caused by old age (43). In this review, the discussion was categorized into two parts of: (1) factors associated with social participation of community-dwelling older adults, and (2) factors associated with participation of community-dwelling older adults in leisure activities.

9.1. Factors Associated with Social Participation of Community-Dwelling Older Adults

Dealing with aging properly requires paying special attention to the factors associated with aging process and eliminating the risks of loneliness and social isolation. In this study, it was demonstrated that the social participation of the elderly was closely associated with the level of education as a personal factor, and with the social network (e.g., relationship with family, friends, etc.) as an environmental factor. Placing the elderly in a large and supportive social network increases their life satisfaction (9). Taking into account the age condition of the elderly, changing the education level of the elderly is not an effective intervention to improve their social participation; however, occupational therapists can facilitate the social participation of them by making an intervention in environmental factors (i.e., creating a supportive and friendly social environment, which improves their life satisfaction) (44). Participation in different activities provides opportunities for different members of the social networks (e.g., family and friend groups) (44). Some studies have investigated the effect of caring on the social participation of elders based on their marital status, and shown that caring significantly and positively affects them. According to the study by Nay et al., The experience of losing a spouse, or in other words, losing a caregiver, is a common issue among the elderly, which, to some extent or even sometimes completely, prevents the elderly from engagement in leisure activities and social participation (45). Andonian and MacRae focused, among other factors, on a variety of social networks and how social connections helped to foster happiness and a sense of well-being, and confirmed that the occupational therapy interventions may have facilitated the social participation and activity engagement of the elderly (46). Encouraging social participation in all forms (i.e., formal or informal) results in the formation of an aged population who is healthy physically and mentally (9, 43).

9.2. Factors Associated with the Participation of Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Activities Related to Leisure

It was found that a variety of factors may have affected different types of leisure activities, among which disabilities as an individual factor and social networks as an environmental factor were the most relevant factors influencing the participation of community-dwelling older adults in leisure activities. Leisure activities were not valued as much as social participation; in families with low levels of socio-economic status. However, greater attention was given to this concept (19, 21, 27). Bertelli-Costa and Neri revealed that socio-economic status and physical health had an impact on the stated leisure activities which could be outdoors or in doors, depending on the level of disability or frailty of individuals (21). Therefore, providing secure economic foundation for the elderly by the government and creating more favorable socio-economic conditions may have facilitated the greater participation of the elderly in leisure activities. Few studies have directly suggested contributing factors other than those previously stated. Santini et al. examined the support provided by social networks for the elderly and the way this support increased the quality of their interactions. They showed that social support may have also improved the quality of the elders’ participation in the leisure activities (25).

9.3. Conclusions

It was concluded that only three articles out of 29 articles were at evidence level I, which highlighted the need for further interventions and creation of a higher evidence level in this field. Since the leisure activities of the elderly were not very much different from the activities associated with social participation, moreover, it seemed necessary to pay special attention to this area. Since social networks were recognized as the most relevant environmental factors both in the field of leisure and social participation, it was recommended that occupational therapists and other geriatric specialists should increase their knowledge about the consequences of social isolation and about the way it affects the mental/physical health, cognition, memory, and overall health status of the frail population, and should make advocacy-based interventions in the social networks in order to give a more accurate prognosis of a future community.

9.4. Limitations

One of the most important limitations of review studies is the existence of the bias risk, which also affected our study since our authoring team participated in both the search and data extraction processes; this limitation may have been addressed by including at least two independent researchers in the search and data extraction processes. Another limitation of the current study was the lack of access to the full text of some articles, despite sending emails to the responsible authors of the articles.