1. Context

Low back pain (LBP) is recorded as a normal medical issue worldwide (1); however, Lopez et al. (2) mentioned that its burden is often considered trivial. LBP is said to be the most common cause of functional disability and absence from work in the world (3). Additionally, LBP is the main source of functional disability and work absence through a significant part of the world (3), and it imposes colossal socioeconomic weight on people, families, groups, industry, and governments (4). Violinn (5) expressed that an expanding measure of research exhibited that low back torment is a noteworthy issue in the low and middle income countries. LBP is reported as a major cause of morbidity in high, middle, and low income countries (6). However, it is relatively under-prioritized and under-funded. Hoy et al. (7) reported under-organization and under-subsidization of LBP might be due to its low position among numerous different conditions incorporated into the previous worldwide studies. They asserted that it might be due to the significant heterogeneity existing among the LBP epidemiological reviews, restricting the capacity to think about it and pool information (6, 7), and furthermore to a limited extent because of the lack of appropriate information. While, it is clear that individuals in all strata of society commonly experience LBP, its prevalence in a number of studies varies, which may be due to factors such as differences in social structure, economy of the developing and developed countries, population studied, environmental factors, and methodological issues, which influence the prevalence of LBP (8). Based on the the aforementioned diversity in epidemiological study of LBP, and paucity of regional or national representative data on LBP prevalence in Nigeria, the current review aimed at assessing the predominance of LBP in Nigeria.

2. Evidence Acquisition

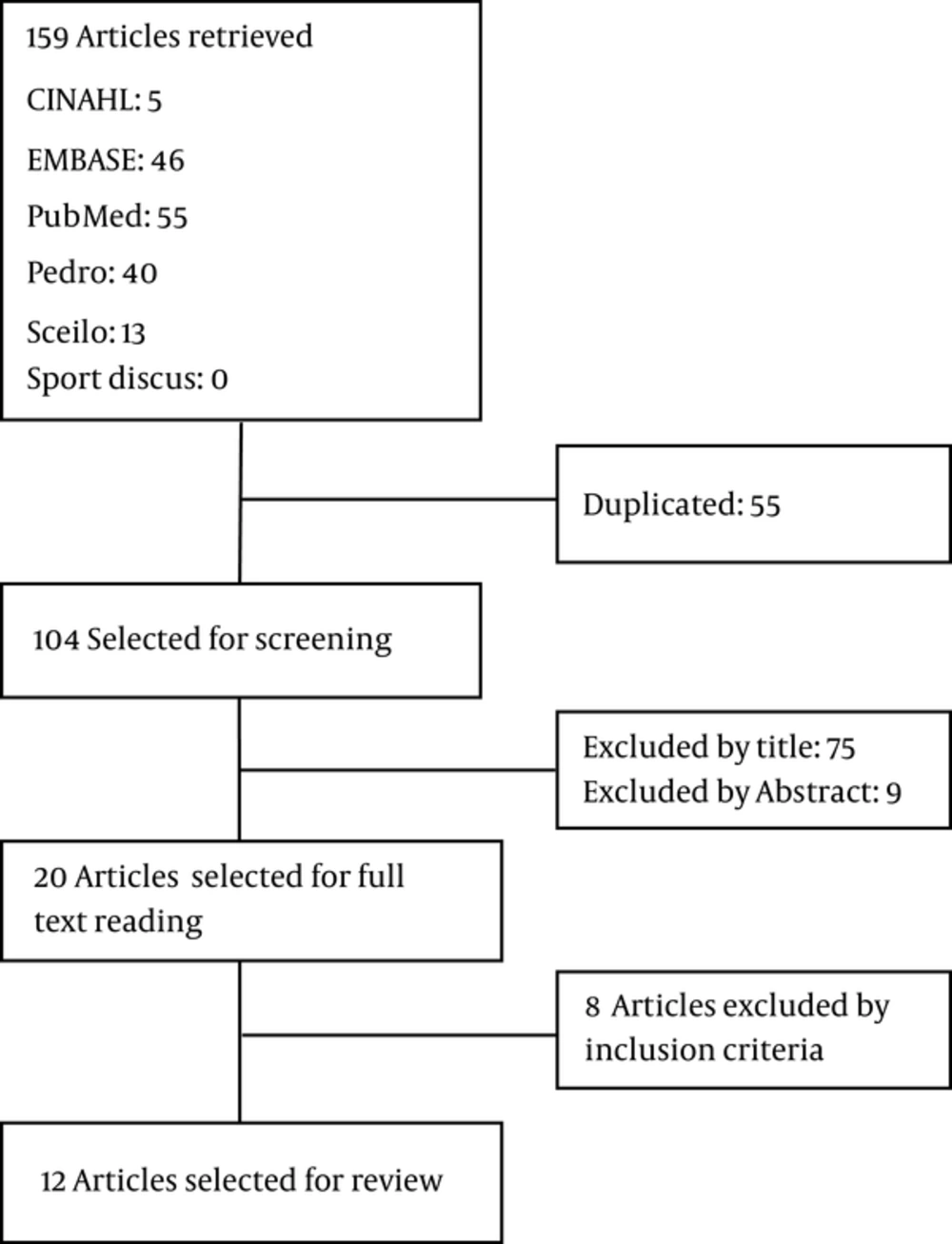

Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the study procedure. The databases of PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, and SciELO were searched from May 1980 to May 2016. The terms “back pain,” “lumbar pain,” “back ache,” “backache,” “lumbago”, “low back pain”, and “lower back pain” were used individually and combined with each of the following: “prevalence,” “incidence,” “cross-sectional,”, “epidemiology”, and “Nigeria”. In PubMed, medical subject headings (MeSH) and Boolean operators were used. In PEDro simple search was conducted, combining search terms separately. The Search strategies are shown in Appendix 1 in the supplementary file. Titles and abstracts of the distinguished review were screened utilizing the inclusion criteria underneath. Full content of conceivably applicable articles were additionally screened to guarantee qualification. The MOOSE checklist was used by 2 independent reviewers who carried out the search based on the inclusion criteria, and studies were excluded if the back pain was due to trauma, infection, malignancy, or pregnancy. Duplicates were also removed.

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Articles were retrieved for this review if they met the following inclusion criteria:

1. Studies that reported epidemiological research.

2. Studies conducted in Nigeria.

3. Studies with the main objectives of the prevalence of LBP.

2.2. Data Extraction

The following headings were used to extract data for the table of evidence: author, year of publication, state, urban or rural area, study setting, sample size, population, age, gender, response rate, LBP point prevalence, LBP 1-year prevalence, LBP lifetime prevalence.

3. Results

The overall search resulted in 12 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The PubMed search yielded 55 results of which 12 were relevant; the PubMed search also yielded a systematic review, but articles that met the inclusion criteria were duplicates of relevant PubMed results. PEDro resulted in 53 studies with nil relevant articles.

Most of the studies were conducted in the Southwestern Nigeria (55.5%), mostly in Ibadan; other Southwestern states are Osun, Lagos, Oyo, and Ondo. Northwestern and Eastern regions accounted for 16% of the included studies each; while, 11% of the included studies were conducted in South regions, particularly Port-Harcourt.

Questionnaires were the common data collection tool. Interview was used in only 1 study (9). Sample size varied from 200 to 900; response rate varied from 53% to 100% in the reviewed studies. Five studies investigated the rural population, while 7 studies investigated the urban population.

Recall periods for LBP varied from the point of prevalence to 12 months and lifetime prevalence.

A study that reported the prevalence of LBP only among males had been conducted on drivers.

Only 3 studies provided a definition for LBP (Table 1).

| Author | State | Urban/Rural | Setting | Sample Size | Population | Age | Gendera | Response Rate, % | Prevalence Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vincent Onabajo et al. (10) | West; East; North | U | School | 207 | Student | 20 - 47 | M = 110 (53.1); F = 97 (46.9) | 71 | Lifetime, 12- month, 1- month, and 7-day |

| Adegoke et al. (11) | Ibadan | U | Schools | 680 | Students | M = 80 (63.5); F = 46 (36.5) | 83.97 | 12- month | |

| Tella et al. (12) | Osun | R | Community | 604 | Farmers | M = 368 (60.9); F = 236 (39.1) | 84 | 12- month | |

| Rufai et al. (13) | Kano | U | Motor Park | 200 | Drivers | 19 - 64 | M = 200 (100); M = 132 (32.48) | 86.3 | 12- month |

| Birabi et al. (9) | Port-Harcourt | R | Community | 310 | Farmers | 18 - 58 | M = 132 (32.48); F = 178; (57.42) | 12- month | |

| Sikiru et al. (14) | Kano | U | Hospital | 408 | Nurses | M = 148 (36.3); F = 260 (63.7) | 81.6 | 12- month | |

| Fabunmi et al. (15) | Ondo | R | Farm | 500 | Farmers | 25 - 84 | M = 276 (55.2) F = 224 (44.8) | 100 | 12- month |

| Sanya et al. (16) | Oyo | U | Industry | 604 | Industrial workers | 20 - 60 | M = 515 (85.3); F = 89 (14.7) | 53 | 12- month |

| Omokhodion et al. (17) | Oyo | U | House to house | 474 | Residents | M = 271 (57); F = 203 (43) | Point prevalence, 12- month | ||

| Omokhodion et al. (18) | Ibadan | U | Workplace | 840 | Clerks | M = 49 (66.2); F = 25 (33.8) | 66 | 12- month | |

| Omokhodion et al. (19) | Ibadan | R | Houses | 900 | Residents | 20 - 85 | M = 570 (63.3); F = 330 (36.7) | 100 | 12- month |

| Omokhodion et al. (20) | Oyo | R | Hospital | 80 | Hospital staff | 20 - 60 | M = 49 (66.2); F = 25 (33.8) | 93 | 12- month |

Summary of Evidence

3.1. Methodological Appraisal

The methodological quality score of the reviewed studies are reported in Table 2. A critical appraisal tool called the Joanna Briggs institute prevalence critical appraisal tool containing 12 items was used. As the questionnaires were the main data collection instruments, criteria 8 and 9 in the critical appraisal tool were not applicable, and thus, were omitted. However, an exception was made for the study by Birabi et al. (9), as it was the only study that used interview together with the questionnaire. Thus, question 9 was omitted and question 8 reinstated. Consequently, the total possible methodological quality score was 10 to 11 (see Appendix 1 in the supplementary file).

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Score, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vincent Onabajo et al. (10) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | N | N | Y | 60 |

| Adegoke et al. (11) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | 90 |

| Tella et al. (12) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | N | Y | Y | 70 |

| Rufai et al. (13) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | 90 |

| Birabi et al. (9) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | 110 |

| Sikiru et al. (14) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | N | Y | Y | 80 |

| Fabunmi et al. (15) | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | 80 |

| Sanya et al. (16) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | N | Y | Y | 70 |

| Omokhodion et al. (17) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | N | Y | Y | 90 |

| Omokhodion et al. (18) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | N | Y | Y | 70 |

| Omokhodion et al. (19) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | 90 |

| Omokhodion et al. (20) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | N | Y | Y | 70 |

Methodological Quality Score

3.2. Low Back Pain Prevalence in Nigeria

The LBP prevalence is reported in Table 3. All the 12 relevant studies reported 12-month prevalence of LBP. The 12-month prevalence ranged from 32.5% to 73.53%. Five studies reported point prevalence of LBP and it ranged from 14.7% to 59.7%. Two studies reported lifetime prevalence of LBP, which were 45.5% and 58%. One study reported 7-day prevalence, which was 11.5%.

| S/No | Author | Point Prevalence | 12-month Prevalence | Lifetime Prevalence | 1-Month Prevalence | 7-Day Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vincent Onabajo et al. (10) | - | 32.5 | 45.5 | 17.7 | 11.5 |

| 2 | Adegoke et al. (11) | 14.7 | 43.8 | 58 | 25.6 | |

| 3 | Tella et al. (12) | - | 74.4 | - | - | - |

| 4 | Rufai et al. (13) | - | 73.5 | - | - | - |

| 5 | Birabi et al. (9) | - | 67.1 | - | - | - |

| 6 | Sikiru et al. (14) | - | 72.4 | - | - | - |

| 7 | Fabunmi et al. (15) | - | 73.53 | - | - | - |

| 8 | Sanya et al. (16) | 59.7 | 59.5 | |||

| 9 | Omokhodion et al. (17) | 39 | 44 | - | - | - |

| 10 | Omokhodion et al. (18) | 20 | 38 | |||

| 11 | Omokhodion et al. (19) | 33 | 40 | - | - | - |

| 12 | Omokhodion et al. (20) | - | 46 | - | - | - |

Prevalence of Low Back Pain in Nigeria

4. Discussion

In the current study, the most reported recall period was 12 months, and the estimate of the 12-month prevalence of LBP ranged from 32.5% to 73.53% (mean estimate: 55.39%); however, the mean estimates should be interpreted with caution due to heterogeneity of data. This finding demonstrated that the 1-year prevalence estimates of LBP in Nigeria were higher than that of the Western societies as 20% and 62% respectively (9), and also among African countries reported 14% to 72% (21).

Hoy et al. (6) described that comparing the prevalence of LBP between populations is challenging because of considerable methodological inadequacies across the studies and troubles to acquire genuine populace gauges. The published reviews incorporated into the current study demonstrated a high risk of methodological flaws such as sample size estimation, study on vulnerable population only (workers) and lack of definition of LBP; all capable of biasing the prevalence data. Other factors that could lead to methodological flaws were lack of detailed outcome measurement tools, and acceptable psychometric properties of the measuring tools (questionnaires). All these methodological shortcomings have ramifications for the validity of the study findings. For example, a clear definition or representation of LBP was not stated by most studies; it could mean that inappropriate or incomplete questions were asked pertaining to the presence or absence of LBP symptoms. A uniform definition of LBP with the end goal of LBP epidemiological reviews would improve the capacity to think and pool results across the studies. Dionne et al. (1) conducted a Delphi procedure to achieve a global concurrence on a uniform definition of LBP to be used in the studies. Their definition included specification of both temporality and topography as follows: pain between the inferior margin of the 12th rib and inferior gluteal folds that is bad enough to limit usual activities or change the daily routine for more than 1 day. This pain can be with or without pain going down into the leg. They explained that: ”This pain did not include the pain from feverish illness or menstruation”. It helped researchers to confine their definition of LBP to an internationally acceptable term that could be used across the population to enhance the quality of epidemiological LBP study.

In the current study, the most commonly studied population groups were workers, and the 12-month prevalence was high, especially among farmers and drivers. This finding was reasonable as most of the respondents were individuals (workers) vulnerable to LBP. This may not be a true representative of the general population including housewives, traders, politicians, athletes, and military personnel that may encompass all and sundry.

5. Conclusion

Analysis of the current review findings showed that the prevalence of LBP in Nigeria was high among workers. However, the high risk of bias may affect generalization of the result. Future studies that may incorporate general population with appropriate methodological design are needed to ascertain the burden of LBP in Nigeria. It may help to guide clinical practice and policy making in allocation of resources for non- communicable diseases management.