1. Context

If a burning sensation occurs in the oral area in the absence of systematic or local disease and clinical symptoms, it is called burning mouth syndrome (BMS) (1-3). The prevalence of this syndrome has been reported from 6% to 15% and even up to 40% in the general population (4, 5). The prevalence of BMS in Iran is estimated at one-third of the population (6). The most common age of onset is the fifth to seventh decades of life, with female predominance (7, 8). The most commonly involved areas of the oral mucosa are two-thirds of the anterior tongue, hard palate, lips, and gums. The burning sensation in the tongue is comparable to when a hot drink has irritated the tongue and so-called scalded tongue. The average pain intensity in BMS is 5 - 8 cm on the VAS (9). Changing of taste sense presents in two-thirds of patients with BMS, and a metallic taste with an increase or decrease in response to saltiness, sweetness, or sourness is found (10, 11). In more than half of the patients, the pain starts spontaneously without any predisposing factors, while in almost a third of the patients, the spread of symptoms is associated with dental procedures, illness, or drugs (12). The severity of the burning sensation in patients is described as mild to severe. Complaints of dry mouth and taste disturbance are also common among patients with BMS (1-4). Its etiology is yet unknown (13, 14). Hence, a multifactorial etiology is considered (14). Degenerative changes, especially the sensation of heat and cold taste and painful stimuli disorders of the central nervous system and peripheral neuropathies, have been effective in causing the disease (11). In addition, the role of psychological factors is plausible in the absence of organic causes, although the relationship between psychological factors and organic causes has not yet been determined (15).

The proinflammatory neuropeptides and cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α are among the most important factors in increasing sensory stimulation circuits and pain sensitivity. These cytokines, chemokines, and other molecules lead to more inflammation and stimulation of inflammatory cells (16). Some studies have suggested the use of interleukins in the diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome. Simcic et al. showed that IL-2 and IL-6 levels in saliva increased, which were associated with disease severity (17). A study by Chen et al. illustrated that burning mouth syndrome is accompanied by an IL-6 drop, followed by chronic pain. Psychological and neuropathic sickness can negatively play a role as pathogens to BMS (18). Boras et al. presented a different result; they found no significant difference between the control and patient groups in IL-6 and TNF-α (19). The results of many studies indicate the critical role of inflammatory mediators, such as proinflammatory cytokines, in the development and persistence of pain due to nerve damage (20-22). Furthermore, some salivary interleukins (IL-6 and IL-2) have been reported to rise in BMS patients and may be responsible for inducing BMS through inflammatory responses (23). However, the comparison between BMS patients and healthy periodontium and normal people showed that the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were similar in both groups (24). Numerous studies have been performed on salivary cytokines in BMS patients. This systematic review study aimed to investigate the salivary biomarkers IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α in BMS.

2. Methods

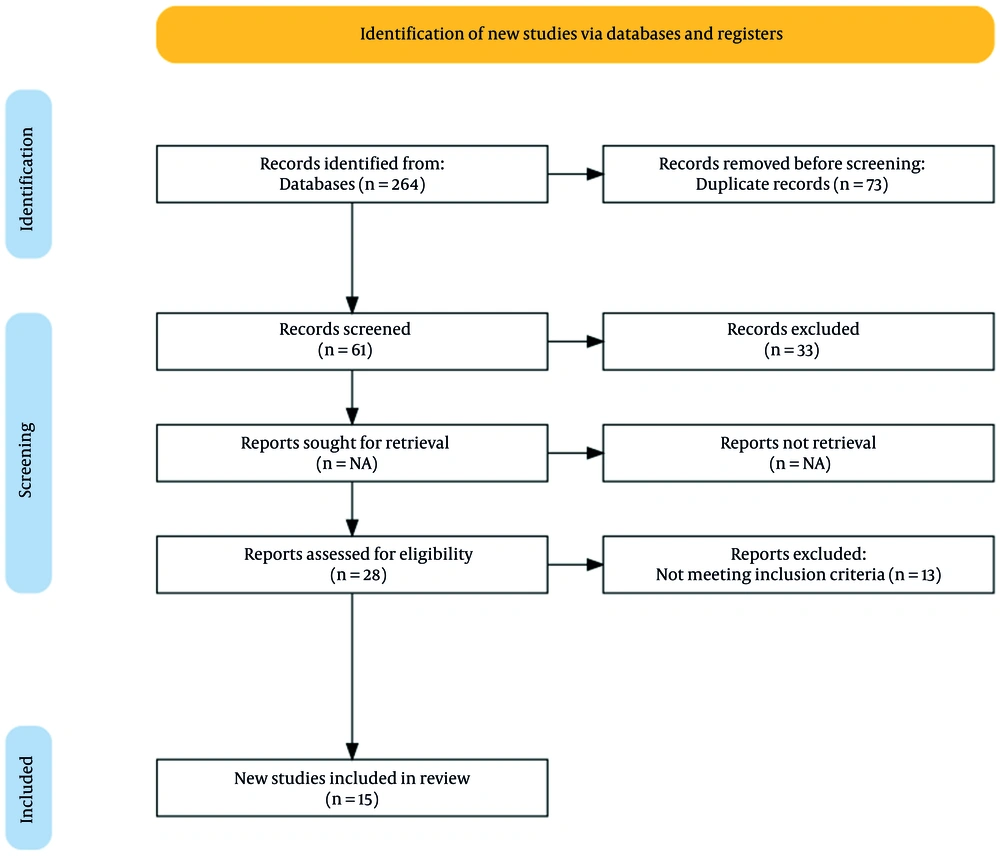

This systematic review was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1400.872). We observed all ethical considerations related to the documents and articles in this systematic review, including compliance with confidentiality in the transmission of scientific data and observance of the moral rights of authors. This study utilized a comprehensive approach and gathered all evidence and studies on the effect of salivary biomarkers IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α on BMS. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of study selection. Articles in Google Scholar, PubMed, SCOPUS, The Cochrane Databases Library, PsycINFO, CINHAL, Medline, ProQuest, Web of Sciences, and other reputable databases were searched. Also, Magiran, IranDoc, SID, and Iranmedex databases from 2000 to 2021 were searched to find Persian articles. Articles were selected by reviewing titles, abstracts, and references. Keywords for searching articles were created using the PICO method, where:

P: Burning mouth syndrome;

I: Treatment;

C: Healthy people;

O: Changes in interleukins IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α.

The search keywords included burning mouth syndrome, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL-6), interleukin (IL-1β), saliva, cytokine, interleukin, burning pain, anxiety, and stress.

Inclusion criteria included articles published from 2000 to 2021, English original articles with a specific and relevant methodology, clinical trials, and in vitro and in vivo studies. Exclusion criteria included review articles, case reports, letters, and articles of poor quality. First, article titles irrelevant to the study objectives were excluded from the study. In the next step, we reviewed the abstracts and full texts of the articles to identify and exclude studies that contained exclusion criteria and were weakly relevant to our research objectives. Two experts assessed the select studies using a risk of bias checklist (STROBE), and the disputes between the two reviewers were referred to a third party. After the final study selection, the necessary information was extracted and summarized in a form (Tables 1 and 2) in Excel software. Endnote X8 was used to organize headings and abstracts and identify duplicates. Finally, 15 related articles were used in this study.

| Author | Year | Title | Study Population | Type of Study | Outcome Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (22) | 2017 | Polymorphisms of interleukin-1β and MUC7 genes in burning mouth syndrome | 40 BMS patients; 40 healthy people | Case-control | Gene polymorphism of IL-1β |

| Guimaraes et al. (25) | 2006 | Interleukin-1beta and serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms in burning mouth syndrome patients | 30 BMS patients; 31 healthy people | Case-control | Genetic polymorphism of IL-1β |

| Suh et al. (26) | 2009 | Salivary levels of IL-1beta, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-alpha in patients with burning mouth syndrome | 40 BMS patients; 20 healthy people | Case-control | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α of saliva |

| Miyauchi et al. (27) | 2019 | Effect of antidepressant treatment on plasma levels of neuroinflammation-associated molecules in patients with somatic symptom disorder with predominant pain around the orofacial region | 48 BMS/AO patients; 44 healthy people | Case-control | IL-1 and IL-6 |

| Chen et al. (18) | 2007 | Serum interleukin-6 in patients with burning mouth syndrome and relationship with depression and perceived pain | 48 BMS patients; 31 healthy people | Case-control | IL-6 of serum; HRSD |

| de Souza et al. (28) | 2012 | Burning mouth syndrome: A therapeutic approach involving mechanical salivary stimulation | 26 BMS patients | Clinical trial (treatment: Mechanical salivary stimulation) | IL-10, IL-6, growth factors, proteins of salvia, and TNF-α |

| Boras et al. (19) | 2006 | Salivary interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with burning mouth syndrome | 28 BMS females; 28 healthy females | Case-control | TNF-α, IL-6 |

| Pekiner et al. (29) | 2009 | Burning mouth syndrome and saliva: Detection of salivary trace elements and cytokines | 30 BMS patients; 30 healthy people | Case-control | Magnesium, zinc, copper, IL-2, and IL-6 |

| Simcic et al. (17) | 2006 | Detection of salivary interleukin-2 and interleukin-6 in patients with burning mouth syndrome | 30 BMS patients; 30 healthy people | Case-control | IL-2 and IL-6 of salvia |

| Xia et al. (30) | 2003 | Correlations among mood disorder, serum interleukin-2, and interleukin-6 in patients with burning mouth syndrome | 48 BMS patients with and without depression | Case-control | IL-2 and IL-6 in saliva; HRSD |

| de Souza et al. (31) | 2015 | The association of openness personality trait with stress-related salivary biomarkers in burning mouth syndrome | 30 BMS patients; 32 healthy people | Case-control | BDNF, IL-10, TNF-α, IL-6, cortisol, growth factor |

| Pezelj-Ribaric et al. (32) | 2013 | Proinflammatory cytokine levels in saliva in patients with burning mouth syndrome before and after treatment with low-level laser therapy | Clinical trial (low-level laser) | TNF-α and IL-6 of saliva | |

| Barbosa et al. (33) | 2018 | Evaluation of laser therapy and alpha-lipoic acid for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome: a randomized clinical trial | BMS with laser; BMS with ALA; SOB with laser; SOB with ALA; control (healthy) | Clinical trial (low-level laser) | TNF-α of saliva |

| Kho et al. (34) | 2013 | MUC1 and Toll-like receptor-2 expression in burning mouth syndrome and oral lichen planus | BMS; OLP; healthy | Case-control | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α |

| Zhang et al. (35) | 2021 | Effectiveness of photobiomodulation in the treatment of primary burning mouth syndrome-a systematic review and meta-analysis | Review study | Pain, TNF-α, quality of life, and IL-6 |

Qualitative Information in the Reviewed Articles

| No. | Author | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kim et al. (22) | There were no significant differences in IL-1β-511 and +3954 genotypes between healthy and sick individuals. There was no significant difference in IL-1β genotype during the symptoms and severity of BMS patients. Genotypic polymorphisms IL-1β -511 and +3954 had no direct relationship with the severity of BMS. |

| 2 | Guimaraes et al. (25) | This article presents evidence that genetic polymorphisms associated with genotypes with high IL-1β production are involved in the pathogenesis of BMS. Modulating IL-1β production may be effective in managing BMS. |

| 3 | Suh et al. (26) | There was no difference in saliva levels of IL-1beta, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-alpha in BMS patients compared to the control group. The level of cytokines in the saliva is mainly affected by the level of blood contamination. |

| 4 | Miyauchi et al. (27) | Before treatment, IL-1β, IL-1, and IL-6 interleukin levels were significantly higher in patients than in controls. These variables decreased after treatment with Duloxetine. |

| 5 | Chen et al. (18) | Psychological and neuropathic disorders may contribute to the etiopathogenesis of BMS. HRSD scores of patients were significantly higher than those of controls. There was no significant relationship between IL-6 levels and depression. |

| 6 | de Souza et al. (28) | Treatment of patients with BMS caused a significant increase in TNF-α. |

| 7 | Boras et al. (19) | There was no significant difference between patients and controls in levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in saliva. |

| 8 | Pekiner et al. (29) | IL-2 and IL-6 levels were similar in BMS and control groups, although IL-6 levels were slightly lower in the BMS group than in the control group. |

| 9 | Simcic et al. (17) | In patients with BMS, the levels of IL-2 and IL-6 in saliva increased, which was associated with the severity of the disease. |

| 10 | Xia et al. (30) | Depression may not significantly affect serum IL-2 and IL-6 levels but is associated with BMS. |

| 11 | de Souza et al. (31) | Patients with BMS showed more neurotic traits and less aperture than the control group. Aperture showed a moderate and negative correlation with IL-6. |

| 12 | Pezelj-Ribaric et al. (32) | IL6 and TNF-α levels were significantly reduced after the low-power laser treatment in the experimental group. |

| 13 | Barbosa et al. (33) | TNF-α levels did not differ between patients with BMS and SOB and the control group. No differences in TNF-α levels were observed after laser treatment in either disease. |

| 14 | Kho et al. (34) | OLP patients showed significantly higher levels of IL-6 in blood and saliva than BMS patients. |

| 15 | Zhang et al. (35) | The biological efficacy of modulation (PBM) may play a role in reducing TNF-α and IL-6 in the saliva of BMS patients. |

Summary of the Results of the Reviewed Articles

3. Results

Our search identified 264 articles related to the search keywords. After screening the titles and abstracts, 61 articles were selected. A further review reduced this number to 28 articles. The full texts of these 28 articles were reviewed, and finally, 15 articles had inclusion criteria and met the objectives of the present study. Regarding the purpose of the research, no review or systematic review study was found.

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), a checklist of clinical trials and case-control studies, was used to assess the risk of bias. There were three clinical trials, 11 case-control studies, and one review study.

In clinical trial studies, almost all clauses were valid, and the studies had a low risk of bias. In the case studies, paragraphs 1, 6, 7, and 9 were not established, and the sample size was small. Overall, this study had a high risk of bias.

4. Discussion

Burning mouth syndrome is a burning pain with no clinical or subclinical findings (1-3). A burning sensation often occurs in multiple areas of the oral cavity. Two-thirds of the mucous membranes of the anterior tongue, anterior hard palate, and lower lip are often involved (36). Facial skin is usually unaffected. There is no relationship between the site of oral involvement and the duration of the disorder and response to treatment (37). The patient’s pain intensity increases throughout the day and peaks in the afternoon. Nevertheless, most patients have no problems at night. Pain levels have been reported to range from moderate to severe, similar to a toothache (38, 39). The disease often occurs in postmenopausal women and is often accompanied by dry mouth. Numerous local and systemic factors are involved in BMS-related symptoms. Systemic factors, such as menopausal disorders, diabetes, and nutritional deficiencies, are important predisposing conditions (1-3). Recently, several studies have shown that clinically insignificant levels of inflammation can lead to inflammatory symptoms and changes in proinflammatory cytokines (40, 41). This study aimed to systematically examine the salivary biomarkers IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α in BMS.

Several studies have examined the possible effect of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α interleukins in patients with BMS. Simcic et al. showed that IL-2 and IL-6 were elevated in the saliva of BMS patients, with proportions attributed to disease severity (17). Some studies have shown changes in interleukins during the treatment of BMS, indicating these proinflammatory cytokines’ role in the burning mouth. Burning mouth syndrome was associated with a significant increase in TNF-α (28). Miyauchi et al. showed that IL-1β and IL-6 levels were significantly higher in patients than in controls before treatment, but they decreased after treatment with duloxetine (27). Pezelj-Ribaric et al. showed that TNF-α and IL-6 decreased after low-power laser treatment (32). Barbosa et al. demonstrated that there is no difference in TNF-α level between secondary oral irritation (SOB) of patients with burning mouths and the control group (33). Also, there was no difference in TNF-α levels after laser treatment in both disorders (33). A systematic review by Zhang et al. showed the biological effects of modulation (PBM) on reducing TNF-α and IL-6 in the saliva of BMS patients (35).

Due to BMS’s chronic nature and prevalence, it is necessary to know an effective treatment method to relieve the patient’s pain and suffering. Although many treatments have been proposed to reduce the symptoms of mouth soreness in BMS patients, there is still insufficient evidence on a standard course of treatment. In addition, evaluation criteria for direct comparison of therapeutic effects are still problematic unless standardized test criteria for evaluating and comparing different treatments are available. For example, it is not yet clear which of the treatment goals, such as relieving the patient’s symptoms and irritation, adapting the patient to chronic pain, improving the patient’s social activity, reducing anxiety and depression following chronic pain, or improving the patient’s quality of life, is more valuable.

An important point that emerges from the results of various studies is that in most studies, the sample size is limited, the duration of follow-up is short, and treatments have been compared with placebo only in a few studies. Most studies on the treatment of BMS have been open-label uncontrolled. Therefore, the interpretation of the results should be carried out carefully after reviewing the quality of the research methodology.

Several studies also exhibited no association between the interleukins IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α and BMS. Suh et al. reported no difference in IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the salvia of BMS patients compared with controls (26). Boras et al. did not observe a significant difference between BMS patients and the control group in salivary IL-6 and TNF-α (19). Pekiner et al. reported similar results on the lack of significant IL-6 differences between patients and controls (29).

Another critical factor attributed to mouth-burning patients is psychological problems. Most people with BMS have mental disorders such as depression, so cognitive and behavioral therapy has been effective in relieving the patient’s pain, and suffering (42, 43). Xia et al. showed that depression might not significantly affect serum IL-2 and IL-6 levels, whereas, it is associated with BMS (30). Chen et al. suggested that psychological and neuropathic disorders may contribute to the etiopathogenesis of BMS (18). Patients’ depression scores were significantly higher than controls in these studies. However, there was no significant relationship between IL-6 levels and depression. In a study by de Souza et al., patients with BMS had more neurotic features and less happiness than controls, whereas happiness was moderately negatively correlated with IL-6 (31).

Kim et al. showed that the T allele level of IL-1β may increase the BMS risk by raising the threshold for psychiatric disorders (22). Guimaraes et al. showed that genetic polymorphisms associated with the high-producing IL-1β genotype are involved in the pathogenesis of BMS. Modulation of IL-1β production may be a suitable approach for BMS management (25). In 2013, Kho et al. showed that patients with oral lichen planus (OLP) had significantly higher levels of IL-6 in blood and saliva than BMS patients (34).

There were three clinical trials in this systematic review. The others were case-control studies with relatively small sample sizes, increasing the risk of bias in these studies. Given the conflicting results, further studies are needed to determine whether IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α interleukins are associated with stomatitis syndrome. We need further clinical studies, as there is a lack of previous studies on the type of treatment and the presence of psychiatric disorders in these patients and the measurement of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels. There were some limitations to this study. First, there were inadequate studies on this topic, and more clinical trials are needed. Besides, further investigation into the relationship between mental disorders and the quantity of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α is suggested.