1. Context

1.1. Coronavirus Disease 2019

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), as a respiratory disease, was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 (1). In the following four months, the disease spread rapidly to many countries around the world. Reports show that most countries will be affected by the aftermath of this global pandemic. Iran has been also involved with COVID-19 since the end of February 2020 (2). From the beginning of this pandemic, all health facilities have been prepared, and many public places and ceremonies, including schools, universities, cinemas, concerts, theater performances, competitions, and government offices, have been closed. Also, home quarantines and social distancing have been mandated in many countries (3).

The majority of people adhere to home quarantine guidelines. In addition, many businesses have been shut down due to the pandemic, and many people have lost their jobs and income (4). During the past couple of years, almost everyone has experienced the fear of contracting COVID-19 around the world. Some have become infected, and some have lost their loved ones. The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated physical damage have caused major psychological problems for people (5). Although the psychological consequences of this disease have been examined in previous studies (6), further research is still needed in this area.

Evidence shows that almost all people will experience a type of mental damage following the COVID-19 crisis (7). These mental problems include emotional breakdown (1), high levels of health anxiety (8), stress and depression (9), fear of death, feelings of loneliness and anger (10), feelings of shame and guilt, stigma, panic attacks, somatic symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and delirium (11). Also, the spread of fear (12), stress due to the unpredictability of the crisis, and uncertainties about the control and scope of the disease (13) are among other problems. People with exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic have experienced threats to their lives, jobs, incomes, and loved ones. Moreover, it is predicted that after this crisis, many people returning to their normal lives will experience disorders such as PTSD (14).

1.2. Posttraumatic Growth

Trauma is defined as an individual’s exposure to an event, resulting in serious injury or threat to the integrity of self and others. Commonly, fear and helplessness are the first responses to a traumatic event (15). Some important traumatic events include injuries, accidents, physical/sexual assaults, earthquakes, floods, storms, and chronic diseases; even witnessing a person’s death or serious injury can be a traumatic event (16). The COVID-19 pandemic is considered a trauma or crisis due to its unexpected and threatening nature and association with death and loss.

Over the past decades, research has moved away from focusing on the negative consequences of traumatic events and studying positive psychological changes after traumatic events. (17, 18). Although a traumatic event is usually perceived as a threat or loss by people, it can provide opportunities for growth and positive changes. These positive changes are known as trauma-related growth, excellence, or posttraumatic growth (PTG) (19).

Posttraumatic growth emphasizes the transformative quality of responding to traumatic events. Overall, PTG entails several domains: (1) Personal changes (i.e., new opportunities for identity development, new possibilities in life, feeling of personal strength, and ability to cope with life circumstances); (2) changes in relationships with others (i.e., establishing positive interpersonal relationships after struggling with a traumatic event); and (3) changes in philosophy of life (i.e., spirituality and connection to a higher power, engaging in spiritual development, and appreciation for life) (20, 21).

Following a traumatic event, an individual may experience disruptions in relationships, challenges to their values and beliefs, family and social roles, and desires and needs (22). Such experiences can lead to an appreciation for life, expanding interests, compassion, and empathy, closer relationships with others, new coping skills, and finally, access to more personal and social resources (21). Posttraumatic growth, as a construal of meaning, signifies a benefit attribution to the question "What for?" (23). Posttraumatic growth has been described as a type of self-enhancing appraisal that can help us cope with a threat (24).

The PTG may develop soon after a crisis and persist for four to five months (25). The transformative nature of PTG is arising from a personal struggle (26).

Following exposure to a traumatic event, personal, environmental, and event-related factors influence the development of PTG through cognitive appraisal processes and coping resources. The personal factors include demographic characteristics, personal resources, and psychological capital, such as self-efficacy, self-confidence, resilience, optimism, motivation, mental health status, and Previous experiences (27).

The environmental factors include social relationships, support from family, friends, society, and financial resources (28). Event-related factors include the severity, duration, time, and scope of the traumatic event. These factors highlight the importance of coping approaches such as rational analysis, positive reappraisal, and active coping for growth (22).

Post-traumatic growth can be considered both as a process and as an outcome of constructive cognitive processing. The PTG process begins when a traumatic event (e.g., the COVID-19 crisis) challenges or destroys a person's cognitive scheme toward life. On the other hand, PTG entails coping processes, adaptation to the traumatic event, and a positive attitude toward the world (29, 30). According to this background, the key question is: How can the COVID-19 crisis be an opportunity for PTG, and how can patience, which is a religious variable, facilitate PTG?

2. Evidence Acquisition

The present study was a narrative literature review (31). Content analysis is a research method with the aim of generating new knowledge through analysis and presentation of facts. Its purpose is to achieve a comprehensive description of the phenomenon, and its result is to analyze the concepts or categories describing the phenomenon and its result is to build a model, conceptual system, conceptual map, or classification. In this study, the qualitative content analysis method (deductive type) was used based on previous knowledge (32). The processes of this analysis include three main phases: Preparation, organization, and reporting.

In the preparation phase, the following keywords were searched: Post-traumatic growth, patience. The sources used were the Holy Quran and any books in the field of Islam. Scopus and Google Scholar databases were also used to search for articles with the keywords: "Patience" and "PTG." In this regard, the views of Islamic philosophers such as Muhammad Hussain Tabatabai on the interpretation of the Quran were considered. Additionally, we manually searched the reference sections of relevant review papers, dissertations, book chapters, and empirical articles (in Persian) to identify any studies that had not been identified in the literature databases. In this review, we obtained a doctoral thesis, two master's theses, and four articles in the Persian language. In all these references, Quranic concepts were used in conceptualizing patience.

In the organization phase, we started with a predetermined set of categories or codes and then applied them to the data in a top-down approach to meaning-making. The categories were done based on the patience process. The sub-codes included acceptance, positivity, responsibility and commitment, faith, hope, reliance, trust, and reliance.

In the reporting stage, after extracting the concepts, the relationship of these findings with the variables of this study was checked. Related concepts were synthesized using thematic analysis and open coding. A process in which concepts are divided into categories based on their characteristics. This was done through several studies of coded content, where relationships between themes and overarching concepts were determined. Then, all the entered studies and identified concepts were grouped in relation to each other. Then, the concepts and fields were explained in detail (32).

3. Results

3.1. Model of Patience for Posttraumatic Growth

Patience is defined as part of resilience. Resilience refers to one's ability to bounce back from trauma, resist illness, adapt to stress, and thrive in the face of adversity (33). It is also associated with equanimity, perseverance, self-reliance, meaningfulness, existential aloneness, a sense of humor, and feelings of self-efficacy, patience, optimism, and faith (34, 35). From our point of view, although patience has a relationship with resilience, it is important to consider it as a distinct concept.

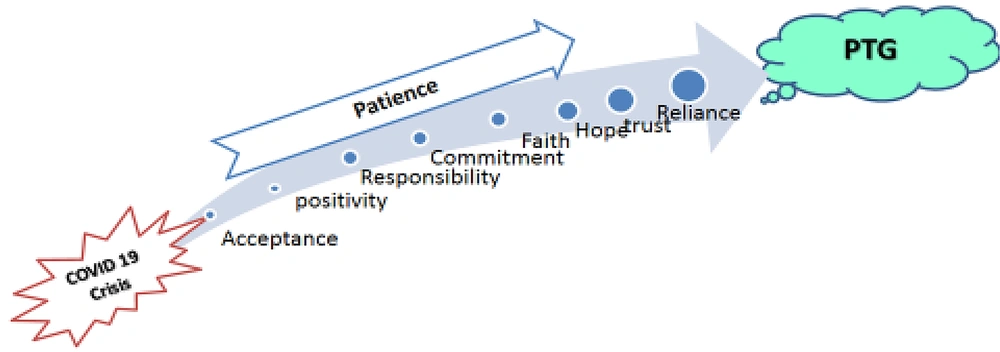

Patience is a largely religious concept and a product of one’s trust in a higher power. It entails understanding the principles of how humans operate mentally and spiritually to experience a more secure state of mind (36). It has been claimed that trauma leads to spirituality, and spirituality, in turn, results in PTG (37). In our opinion, patience not only increases one's capacity to endure trauma but also improves PTG (38). Here, we conceptualized the process of patience to facilitate PTG in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. The patience process for PTG is shown in Figure 1.

3.2. Patience Process

It is a combined and integrative model of emotional, cognitive, and spiritual approaches. A person can grow by taking advantage of the emotions associated with the crisis. Growth requires the cognitive processing and emotional engagement associated with emotional distress caused by trauma (21). Also, growth has a spiritual aspect, which enables people to reach perfection and achieve self-actualization. According to our model, patience involves acceptance, positivity, responsibility and commitment, faith, hope, trust, and reliance (39). Here, we discuss our patience model for the COVID-19 crisis in six steps:

3.2.1. Step 1: Acceptance

Denial is the first and most important step in responding to a crisis. In critical situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the severity of stress is very high, and for some people, it exceeds their tolerance and capacity. These individuals tend to suppress their emotions (40) and may deny their real-life experiences. This led many people to deny the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic at first. In Iran, it took one month for people to accept the reality of COVID-19. Denial was also common among politicians. Therefore, people may misinterpret the critical nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. They may show strong behavioral and emotional reactions, such as obsessive washing and disinfecting or excessive avoidance of human contact.

Whether a person's maladaptive response to a crisis is, denial or catastrophic depends on his/her emotional processing style. The reaction of some people to the COVID-19 pandemic was apathetic, and they did not exhibit any preventive behaviors against the disease. On the other hand, some people viewed it as a catastrophe and showed signs of panic and anxiety. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people, even officials, did not accept the risks and did not follow the health and preventive guidelines. As a result, many countries experienced an increase in morbidity and mortality since the outbreak (41).

Generally, prolonged denial can be delusional. The denial phase usually ends with the acceptance of reality. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people gradually accepted its threats and took precautionary measures (39). The sooner the risks of a crisis are accepted, the sooner it will be prevented, and less damage and harm will be done. In countries where the acceptance of COVID-19 was delayed, the amount of damage increased. Conversely, in countries where the risk of COVID-19 was accepted earlier and faster, the rates of morbidity and mortality were much lower (42).

Patience begins with the acceptance of reality. It entails one’s ability to cope with adverse circumstances, calamities, and difficulties and endure difficult times without blaming oneself or others. It enables people to create a meaningful life without feeling remorse, anger, or apprehension when confronting hardship. For example, regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, developing patience can prevent people from complaining about the quarantine conditions, the operation of healthcare systems, and family members' behaviors (43). When people accept the reality, they start to follow preventive protocols, find peace of mind, and adjust their life plans to new circumstances. Changing cognition and helping individuals adopt emotion regulation strategies can help individuals actively reevaluate traumatic experiences (44).

Generally, patience is the most difficult reaction to a crisis because it can prevent common destructive behaviors, such as remorse, anger toward oneself and others, high-risk behaviors, and revenge. It is very difficult for a person to control and regulate his/her emotions in times of uncontrollable crisis (45). However, by regulating and managing emotions, healthy and positive thinking will be promoted.

3.2.2. Step 2: Positivity

According to a study by Tedeschi and Calhoun on PTG, traumatic events can stimulate cognitive processing. When stress induced by traumatic events transforms into constructive processing, individuals can reconstruct their assumptions, resulting in positive changes (21). In this cognitive model, deliberate rumination is a key factor in PTG (25). When people are exposed to a crisis, they reappraise their personal goals and worldviews. It is important to reduce emotional distress following a crisis through recurrent positive rumination. Negative rumination leads to signs of injury and disorder, whereas positive rumination leads to growth. This step depends on whether rumination supports negative or positive thoughts. Such cognitive processing directs the person toward problem-solving and positive thinking. Therefore, positive appraisal plays a role in experiencing post-traumatic growth (44).

When trauma survivors struggle to successfully cope with a crisis, they tend to intentionally ruminate. Therefore, rumination is a form of constructive cognitive processing that allows trauma survivors to find the meaning of life and re-evaluate their lives positively. (21, 46). On the other hand, positive thinking requires one to maintain a calm and open attitude and show self-care and self-regulatory behaviors. When a person accepts the reality of a crisis, he/she can not only survive in the face of adversity without complaining but can also show more gratitude in his/her behaviors (47).

People who believe that every incident in life happens for a reason, whether they are aware of it or not (43), can think positively in times of crisis and remain optimistic. These individuals are satisfied with their own efforts and are optimistic about their ability to manage and control the problem. They consider home quarantine as a great opportunity for doing things they have always dreamed of doing. Therefore, optimism, as discussed by Tedeschi and Calhoun (21), leads to an effortless passage through crisis. These individuals do not allow disturbing thoughts and seek positive behaviors. Overall, positive people can remain calm, strong, and persistent in times of crisis and work hard to achieve their goals and resolve problems (47).

3.2.3. Step 3: Responsibility and Commitment

A sense of responsibility is one of the positive behaviors in times of crisis. Patients usually feel responsible for overcoming the challenges of their disease (43). The first step when exposed to trauma is to feel responsible for oneself and show self-control and self-care behaviors in the face of adversity (48). Self-control is defined as the ability to control emotions, desires, and thoughts, to practice forgiveness, and to show tolerance (47). The second step is related to empathy and a sense of responsibility toward people around us and caring for our family. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to empathy and help our family members avoid exposure to the virus (49), encourage them to take preventive measures without fear, help them overcome their boredom and tiredness during home quarantine, and encourage them to be happy and take advantage of their free time (50).

The third aspect of responsibility and commitment is the feeling of social responsibility. In the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to consider helping the community (49). In Iran, many people have come to the help of others in need. Some people work voluntarily in hospitals, produce masks, make free donations to hospitals, and help the poor and those who have lost their jobs and income (39). Overall, a sense of responsibility creates energy and strength in people and helps them go through critical events. Also, patience has a relationship with forgiveness, and patient people are normally forgiving (43).

Another important aspect of responsibility and commitment is having a deep commitment and purpose in life. Everyone must be committed to achieving an important goal in life. After overcoming a crisis, we have the best opportunity to understand and work for our main purpose in life. In other words, determination, diligence, and effort are necessary in the face of difficulty. Overall, patience is not a strategy of retreat, withdrawal, or passivity but is an attempt to transform and realize our hopes and dreams. Fear is one of the most important barriers to patience; therefore, it is necessary to overcome it and be courageous. Also, changes in life goals and plans and lifestyle modifications are necessary (51). However, achieving PTG can be difficult, leading to pain, suffering, and fatigue for the individual; therefore, perseverance is essential during a crisis.

3.2.4. Step 4: Faith

Another step to achieve PTG is faith and spirituality. Faith is the ability to refrain from things that are prohibited by religion and to show adequate strength to follow God’s commands (48). Generally, faithful people become stronger emotionally during a crisis and strive to live a more meaningful life by overcoming it. One of the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic is conflicts and challenges in people's fundamental beliefs and values. At this time, basic questions about the value of life and life after death are raised. Also, some social changes following the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the closure of mosques and places of worship and the impossibility of visiting patients or saying goodbye to dying loved ones, have been influential. When a crisis occurs, some people may wonder if it is God's wrath, if it is a divine test, or if it is an opportunity for personal growth; therefore, it provides an opportunity for people to think and rebuild their values.

According to a study by Bray (52, 53), in the psycho-spiritual transformation model of PTG, trauma may result in spiritual development. Studies show that exposure to trauma can shatter the core belief system of individuals in many societies. Religious people believe that trauma and suffering are God’s will or design (54). There are some speculations that people have grown spiritually since the COVID-19 pandemic. They may fundamentally change their views about themselves and the world, try to find meaning for their suffering, and pursue spiritual solutions. Overall, closeness to God can be effective in an individual’s adaptation to a disease (55). This can be achieved through saying prayers, reading religious texts, and feeling close to God, all of which provide a powerful, supportive, available, and reliable source, preparing them for current and future problems. It has been shown that spiritual meaning-making can alleviate suffering.

Religious people accept crisis as a divine test. This belief plays an important role in enduring suffering (56). Spirituality involves self-awareness, consciousness, and self-transcendence. It is among the most important contributors to the positive outcomes of PTG (57). Religious coping reduces the adverse psychological effects of trauma. Trauma often promotes spirituality among survivors and may help them find meaning during a traumatic experience (58).

In the Holy Quran, God says "perhaps you hate a thing, and it is good for you; and perhaps you love a thing, and it is bad for you. And Allāh knows, while you know not" (Verse 216, Surah Al-Baqara). Also, God says, "Do not despair of the mercy of Allāh” (Verse 53, Surah Az-Zomar). According to the abovementioned quotes and also regarding the fact that in the Holy Quran: “With hardship ease” (Verse 5, Surah Al-Sharh) (48), it can be concluded that difficulties and crisis will definitely pass by, and ease and relief will come back to human beings’ lives (49, 50).

Therefore, it seems that in a crisis situation such as COVID-19, the human duty, in addition to dealing with the damage caused by it, is to improve the psychological capacity of people to take opportunities to grow and improve their existential capacities.

Meaning-making is generally believed to be a critical aspect of recovery and growth after stressful events and experiences. It allows people to have a balanced perspective of events in life and helps them assume a less self-critical stance toward their failures in life. They may even use their experience as an opportunity to grow rather than ruminate on their failures (59).

3.2.5. Step 5: Hope

Exposure to trauma and crisis can be a major threatening factor for hopefulness. People with COVID-19, family members who are in quarantine or at risk of the disease, and especially those who have lost a loved one to the disease may experience very painful emotions. These people may feel strong emotions (60), such as loneliness, disappointment, and helplessness. Also, they may experience feelings of isolation and intense mourning. Some common feelings at this stage include depression, pain, silence, loneliness, discomfort, helplessness, despair, existential thoughts, emptiness, weakness, and preoccupation with negative thoughts (61).

The feeling of hopelessness is an important indicator of PTSD, which may even lead to suicide. Previous studies have reported suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic (12). Hopelessness is characterized by negative expectations about the future and is observed in many psychological disorders. During a crisis, hopeful people focus on the future, and survivors usually begin to experience moments of happiness as they learn to separate themselves from the experience of loss and identify new goals and opportunities; they also make some new plans with strength, passion, and hope (61).

Generally, hope is defined as a positive cognitive state to achieve a goal. It is the general expectation that positive outcomes can be achieved based on a sense of goal-directed determination as a result of one's interactions with the environment. In other words, it is one's capacity to imagine his/her ability to create paths toward goals and to motivate oneself in that direction. Overall, hopefulness increases when a person finds a better way for the future (62). Hope has two main stages, each consisting of two steps. The first step is to instill hope, and the second step is to increase hope and maintain it (63).

According to our observations and reports, hopelessness might have played a role in the death of some patients with COVID-19, especially in the early days of the pandemic, when inpatients experienced the peak of despair as they witnessed other patients die. Also, waiting for rewards (64) and delaying some instantaneous desires to achieve greater goals in the future (65-67) is similar to waiting. Hope, trust, and expectation are closely related concepts that make hardships bearable for people. In the hope of reward, one endures hardships and even transcends his/her capacity. The hope of success and belief in inevitable growth are the focus of this stage.

3.2.6. Step 6: Reliance and Trust

Patience enables people to adapt to difficult quarantine conditions and disease. Trust in God, as a coping strategy for anxiety and depression, is of even greater importance (68). People with patience tolerate and accept the pain and difficulties of life consciously. They are familiar with the reality of their problems and know that it will help them grow. These people maintain their patience and faith when facing adversity (69).

People with patience believe that trust in God will help them solve their problems and overcome trauma. They are submissive to God’s will (43) and believe that their attempts to overcome a catastrophic event are a great success and progress; therefore, they appreciate their day-to-day efforts to cope with difficult times. The highest level of patience is when a person fully surrenders to God and feels empowered for a great life (43). These people believe that all suffering and happiness in life come from God and that he gives us the power to survive (70). Overall, belief in God removes all anxiety and anger and improves peace of mind (71).

Moreover, self-confidence can boost an individual’s emotional strength. The highest level of strength can be achieved when one relies on a higher power to overcome trauma and grow as a strong individual. The COVID-19 patients, physicians, nurses, and those involved in this pandemic will experience this stage in the coming months and years, provided that the previous steps are taken. Everyone’s strength and power will increase up to several times at this stage. They will be able to do the things they were afraid to do or did not have the chance to do; this can lead to self-actualization, which is the highest level of PTG (72).

3.3. Patience and Resilience

Patience and resilience have some overlaps in meaning, which should be considered. Both concepts refer to coping styles in regard to life expectations, roles, hardships, challenges, risks, transitions, and health problems (73). Although both terms represent personality traits, they are characterized as more of a process than a present-or-absent trait. It is believed that individuals have different levels of these qualities relative to their age, gender, experience, education, available resources, cultural background, beliefs and values, religiosity, and individual, family, social, and geographical conditions.

On the other hand, the theoretical constructs of resilience include resistance, flexibility, adjustment, perseverance, capacity development, and change (36). Here, a question may arise as to whether patience is the same as resilience. In our opinion, there are differences between patience and resilience. Some of these differences have been further mentioned in order to clarify the distinction between these two concepts and address their overlaps. First, patience is a largely religious concept and a result of trust in a higher power. It entails understanding the principles of how humans operate mentally and spiritually to reach a more secure state of mind. However, the theoretical concept of resilience, which is predominantly based on health approaches, is characterized by the individual’s adaptive responses to life’s traumatic or adverse events. It involves one’s capabilities to take effective measures and trust in oneself to deal with change. Moreover, this concept signifies the ability to bounce back or withstand major or multiple stresses in life and the capacity to thrive despite adversity, change, uncertainty, and unpredictability (71).

Second, the development of patience includes acceptance, positivity, responsibility and commitment, faith, hope, and trust and reliance. On the other hand, the development of resilience involves resistance, adjustment, contentment, flexibility, bouncing back, awareness, perseverance, growth, and competence (74, 75). Finally, patience encompasses resilience and even transcends it, while resilience helps individuals cope with adversity, achieve adjustment and growth, and bounce back from trauma. Patience has a similar course of action, except for returning to the previous function while transcending to higher insight and understanding (positive expectations and idealism).

4. Conclusions

The development of patience involves emotional restraint (avoidance of complaining, expressing anger or inappropriate instinctual desires, and revenge), tolerance (having peace of mind, self-care, self-regulation, and openness), endurance (showing tenacity, perseverance, and firmness), and positive expectations (anticipating relief, hope of salvation, and reward or perfection) (39). Patience can enable people to overcome any problem in their life. These people, when faced with a crisis, consider it as an opportunity for their own growth and development. Overall, crisis increases the society's patience (76). In other words, during a crisis, patience is inevitable for overcoming and coping with problems. In times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, people need to practice patience at a higher level than before. It is worth mentioning that during crises, some people tend to reach PTG.

Along with the damages that the COVID-19 pandemic has caused, it has also provided opportunities for people to develop their existential and skill-building capacities. Some of the psychological achievements it has caused include emotional regulation, identifying individuals' capacities, controlling anxiety, psychological adjustment, reducing death anxiety, remembering God, hope and trust in God, creativity, self-esteem, courage, responsibility, patience, understanding of the value of health, empathy, and social support (77, 78). As a matter of fact, if we focus on growth when exposed to a crisis, we can expect more people to achieve PTG. In conclusion, patience and its steps, outlined in this article, can facilitate and expand PTG.

The development of this model and its training by counselors and therapists can help people who have severe anxiety disorders and depression caused by bereavement crises and other crises.