1. Background

Gender identity disorder (GID) refers to a condition characterized by a clear incongruence between an individual’s experienced or expressed gender and their biological gender at birth (1). According to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V) criteria, this condition must persist for at least six months and be associated with clinical distress or impairment in interpersonal, social, or professional functioning, or with an increased risk of health complications (2, 3). Gender identity disorder can result from abnormal sexual function, a common and treatable issue that significantly impacts individuals' lives and causes emotional tension (4). Broadly, GID signifies dissatisfaction or conflict with one’s biological gender assigned at birth, leading to clinical challenges. From a psychological perspective, it highlights the distinction between sexuality and gender (5).

The prevalence of GID varies across countries, reported as ranging from 1:11,900 to 1:45,000 for male-to-female transsexuals and 1:30,400 to 1:20,000 for female-to-male transsexuals (6). In Iran, the prevalence of GID is estimated at 1.46 per 100,000 individuals (7). Mental and behavioral disorders are particularly common among people with GID (8). According to de Freitas et al., an average of 53.2% of individuals with GID experience at least one mental disorder during their lifetime (9). Studies report rates of depression and anxiety in people with GID ranging from 48% to 62% and 26% to 38%, respectively (8). A study by Meybodi and Jolfaei revealed that the prevalence of personality disorders among individuals with GID is 81.4% (10). Social pressures, frequent rebukes for unexpected behaviors, living with guilt, and emotional suppression are among the significant contributors to comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, and aggression in this population (11, 12). Accurate diagnosis of these psychiatric disorders can provide better insights into GID and improve management strategies (10).

Regarding Iran’s cultural context, particularly the traditional culture of Ilam province, individuals suffering from GID may not only be denied recognition as patients but may also have their behaviors interpreted as delinquent or misguided. Furthermore, the social acceptance of the behaviors of individuals with GID is challenging, creating an additional source of anxiety for these individuals and rendering them more vulnerable to personality and psychological problems (13, 14). Gender confusion causes perplexity and disruption in a person’s appropriate sexual role and behavior, further deteriorating social and interpersonal relationships and leading to sexual deviance and psychological distress (12). Additionally, many individuals with GID are married, and some have children. For these individuals, gender transformation is often a significant source of anxiety and aggression, frequently culminating in divorce (12, 13).

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in individuals with GID remains an area of considerable uncertainty, as there is a lack of research exploring the relationship between personality type and the prevalence of psychiatric disorders.

2. Objectives

Given the significance of the issue, this study aimed to determine the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and aggression among individuals with two different personality types (A and B) suffering from GID.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This cross-sectional study included all patients (n = 40) who were selected by census and referred to the Forensic Medicine Department of Ilam city in 2020 for gender transformation. The inclusion criteria were: Being 18 years of age or older, having a diagnosis of GID, and being a resident of Ilam. Patients who did not provide informed consent were excluded. All participants received psychological counseling from a trained psychiatrist. The diagnosis of GID was made by a psychiatrist through a clinical interview, and all patient data were collected under the supervision of the psychiatrist.

3.2. Tools

To determine the levels of depression, anxiety, personality type, and aggression, the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Aggression Questionnaire (AGQ), and Spencer’s A or B Personality Type Questionnaire were used, respectively. Other study variables were then analyzed based on these separate groups. The BDI-II consists of 21 items scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, which evaluate symptoms related to depressive disorders over the past two weeks, with a total score calculated out of 63. Scores of 0 - 13 are considered minimal, 14 - 19 mild, 20 - 28 moderate, and 29 - 63 severe depression (15). The BAI also consists of 21 items, each scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3, with scores of 0 - 9 indicating normal levels of anxiety, 10 - 18 mild, 19 - 29 moderate, and 30 - 63 severe anxiety. The AGQ includes 21 items, with each item scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3, where higher scores indicate greater levels of aggression. In Spencer’s A or B Personality Type Questionnaire, the cut-off score is 13; individuals scoring below this threshold are designated as having a type B personality, while those scoring 13 or higher are categorized as having a type A personality (16). The Persian version of the AGQ has demonstrated test-retest reliability of 0.70 and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87, ensuring its validity and reliability for this study (17).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The patients' data were analyzed using the t-test, Fisher’s exact test, and linear regression with STATA 12 software. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of the data distribution for depression, anxiety, and aggression, with results indicating normal distribution (P > 0.05). The adjusted R2 value was used to identify the best-fit model for the data. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

Of the study participants, 95% were women, and 5% were men. Ten participants (25%) had academic education, while 25 (75%) had diplomas or lower education levels. The mean ± SD Beck depression scores were 16.23 ± 8.23 for individuals with personality type A and 13.83 ± 10.37 for those with personality type B. The overall mean ± SD depression score was 15.2 ± 9.2, and the mean anxiety score was 21.4 ± 13.2. The mean ± SD Beck anxiety scores were 23.36 ± 13.11 for individuals with type A personality and 13.32 ± 19.00 for those with type B personality. The average aggression score for individuals with type A personality was significantly higher than for those with type B personality (Table 1). Among participants with type B and type A personalities, 11 (64.1%) and 10 (45.5%) individuals, respectively, exhibited no symptoms of depression, while six (33.3%) and one (4.6%) had no anxiety symptoms. Additionally, 22 (55%) of the participants had type A personality, and 18 (45%) had type B personality.

| Characteristics | Total Sample (N = 40) | Personality Type A (N = 22) | Personality Type B (N = 18) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 19.5 ± 1.7 | 19.68 ± 0.3 | 19.3 ± 0.4 | 0.45 b |

| Gender | 0.70 c | |||

| Male | 2.0 (5) | 1.0 (50) | 1.0 (50) | |

| Female | 38 (95) | 21 (55) | 17 (45) | |

| Education | 0.08 c | |||

| Diploma | 30 (75) | 14 (47) | 16 (53) | |

| University education | 10 (25) | 8 (80) | 2 (20) | |

| Depression | 0.45 c | |||

| No or very low | 21 (52) | 10 (48) | 11 (52) | |

| Mild | 3 (8) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Moderate | 12 (30) | 7 (58) | 5 (42) | |

| Severe | 4 (10) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | |

| Anxiety | 0.06 c | |||

| No or very low | 7 (17.5) | 1 (14) | 6 (86) | |

| Mild | 7 (17.5) | 6 (86) | 1 (14) | |

| Moderate | 12 (30) | 7 (58) | 5 (42) | |

| Severe | 14 (35) | 8 (57) | 6 (43) | |

| Aggression | 41 ± 10 | 45 ± 2 | 36 ± 2 | 0.01 b |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

bt-test.

c Fisher's exact test.

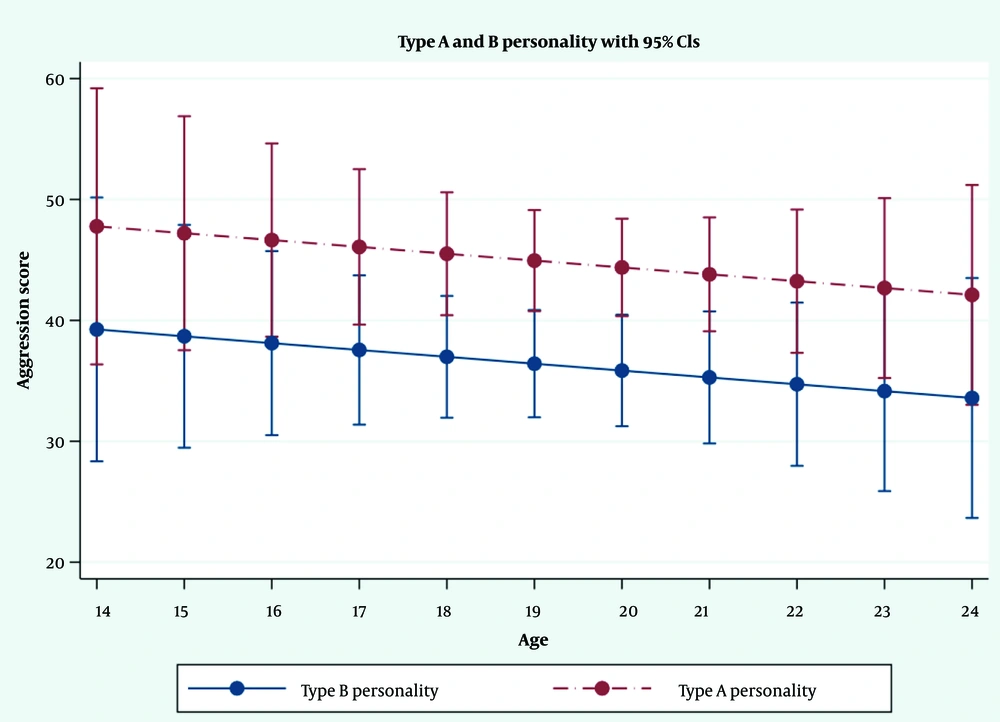

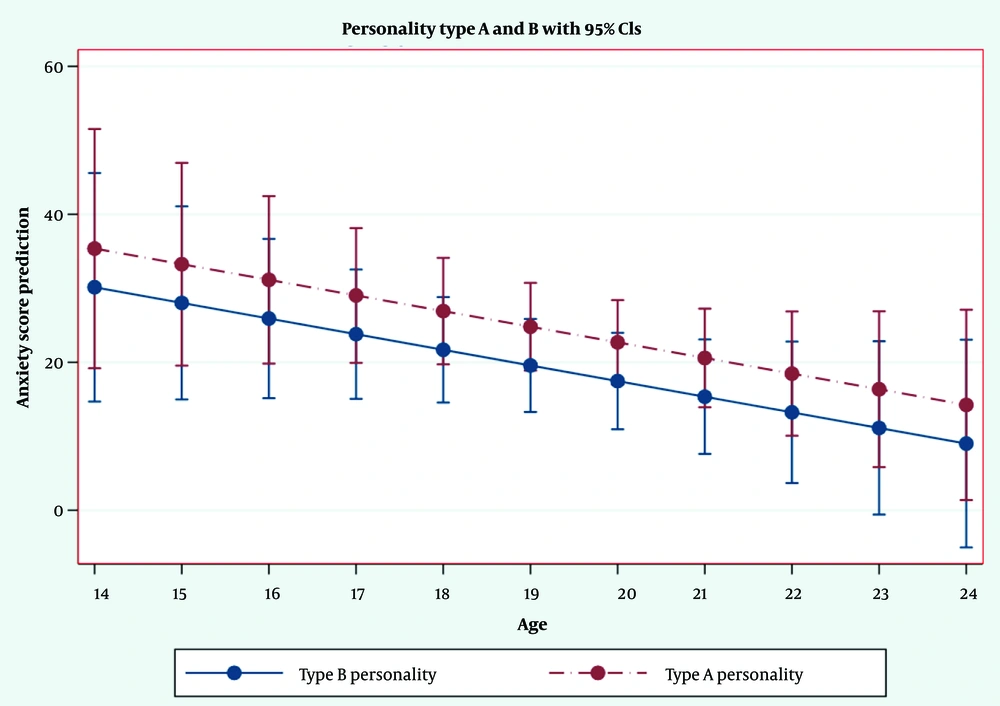

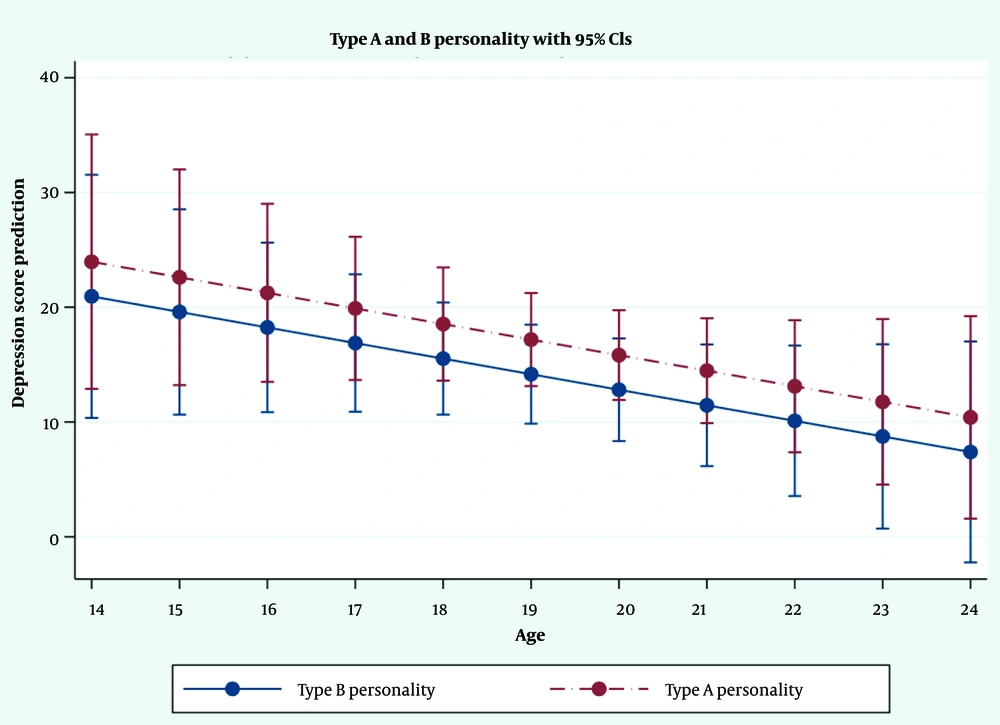

There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age or depression symptoms; however, a near-statistically significant difference in anxiety symptoms was observed (P = 0.06), with anxiety being slightly more prevalent in individuals with type A personality than in those with type B personality. As shown in Figures 1 - 3, although aggression, anxiety, and depression scores were higher for type A personality than for type B, the difference between these two personality types diminished with age. However, linear regression analysis revealed a significant relationship between type A personality and aggression. Specifically, aggression levels increased by an average of 6.23 points for individuals with type A personality compared to those with type B personality (P = 0.03) (Table 2). No significant relationship was found between personality type and anxiety or depression based on the linear regression model (Table 2) (Figure 1).

| Variables | Depression | Anxiety | Aggression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient (95%CI) | P-Value | Regression Coefficient (95%CI) | P-Value | Regression Coefficient (95%CI) | P-Value | |

| Personality type | ||||||

| Type B | 1 a | - | 1 a | - | 1 a | - |

| Type A | 1.23 (-4.47, - 6.93) | 0.67 | 3.11 (-5.43, - 11.64) | 6.23 (0.61, - 11.85) | 0.03 b | |

| Model summaryc | R 2 = 0.25; adjusted R2 = 0.16 | R 2 = 0.18; adjusted R2 = 0.10 | R 2 = 0.36; adjusted R2 = 0.29 | |||

a Reference category.

b Significant.

c Adjusted model for age, sex, and education.

5. Discussion

In our study, a higher proportion of participants were classified as having type A personality. Individuals with type A personality tend to exhibit more aggressive behavior in their interactions with others. Although the mean aggression score was low in our sample population, individuals with type A personality demonstrated higher aggression scores compared to those with type B personality, reflecting a greater tendency toward aggressive behavior in this group. Previous studies have established a relationship between anxiety and aggression, indicating that individuals who exhibit higher levels of aggression also tend to experience elevated levels of anxiety. These findings suggest that anxiety may contribute to aggression in these patients, similar to patterns observed in the general population (18, 19). While some studies have dismissed a direct connection between GIDs and aggression, aggression in these patients may stem from factors such as self-destructive behaviors driven by grief, anger, and hopelessness caused by social discrimination, interpersonal relationship challenges, delayed and incorrect diagnoses, and inadequate treatments (19). Previous research has shown that, on average, 53.2% of transgender individuals develop at least one mental disorder during their lifetime (18).

The prevalence of depression in our sample population was 47.5%. Smith et al. (19) reported that transgender women (assigned male at birth) are at high risk of being diagnosed with depression. Similar findings have been observed in transgender men (assigned female at birth) (20). In another study by Heylens et al., the prevalence of mood disorders was reported to be 60% in both transgender men and women (21). A systematic review by Freitas et al. found that 42.1% of transgender individuals suffer from emotional disorders, including depression (9). Weiselberg et al. reported that more than 60% of transgender individuals experience depression (22). Studies have shown that psychological distress in individuals with GIDs is linked to numerous external psychological stressors, such as victimization, harassment, and discrimination (23, 24).

In this study, the mean depression score was higher among individuals with type A personality compared to those with type B personality; however, this difference was not statistically significant. Overall, some degree of anxiety was observed in 82.5% of the participants, with respective rates of 95.5% in individuals with type A personality and 66.6% in those with type B personality. In a study by Heylens et al., the prevalence of anxiety was reported as 28% in their sample population (21), while a systematic review by de Freitas et al. found the prevalence of anxiety disorders to be 26.8% (9).

In the present study, Beck’s Anxiety and Depression Inventories were utilized as screening tools to assess anxiety and depression. The high prevalence of these conditions observed in this study may partly reflect the high sensitivity of these instruments. Furthermore, considering that the patients were interviewed during the COVID-19 pandemic, the elevated rates of depression and anxiety may be partially attributable to the psychological impact of the pandemic. However, the findings of this study are not generalizable due to the limited sample size and the lack of broader applicability.

5.1. Conclusions

Gender identity disorder patients with mental health challenges may experience varying frequencies of disorders based on their gender and personality type. A significant difference was observed between individuals with type A and type B personalities in terms of aggressive behavior. However, despite the high prevalence of mental health issues, no significant difference was found in depression and anxiety between the two groups. It is essential for GID patients to receive appropriate psychiatric interventions, which may include individual therapy, group therapy, family therapy, and social counseling to address their mental health needs effectively.