1. Background

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as the physical, emotional, and mental state related to a person's gender (1). Research has shown that certain diseases can exacerbate sexual problems (2). Among these, breast cancer is notably prevalent among women and is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths (3). Mastectomy, a common treatment for breast cancer, involves removing the breast and often leads to sexual health consequences that require clinical attention (4). The biopsychosocial perspective on sexual health goes beyond mere biological aspects, also considering the psychological factors associated with sexual well-being (5). In recent years, there has been significant research into people's perceptions of sex and related issues. Sexual distress, an important aspect of sexual health (6), involves experiencing negative emotions such as anxiety, worry, feelings of failure, and inadequacy during sexual experiences, which can adversely impact one's quality of life (7). Therefore, it is crucial to study the factors contributing to sexual distress, as understanding these can help develop effective interventions to improve sexual health (7).

In addition to the side effects of mastectomy, survivors often experience various emotional problems after surgery. A study conducted in Iran involving 82 breast cancer patients at Razi Hospital in Rasht, who underwent radiotherapy, found that 32 (39%) suffered from severe mental health issues (8). These emotional difficulties are linked to worsening sexual problems and increased sexual distress (2). Unlike medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, which are not typically associated with sexual distress in women (9), emotional issues significantly contribute to sexual problems in women (10). Moreover, after a mastectomy, many women feel uncomfortable with the changes in their appearance (11). Since women often place a high value on their appearance (12), they usually experience greater psychological distress when dealing with diseases that alter their appearance (11). Indeed, breast cancer and breast surgeries are associated with feelings of lost attractiveness, diminished femininity, and bodily imperfections (13), which are linked to increased distress and sexual problems in women (14). The significant role of body image has been emphasized in recent years, leading researchers to develop tools for measuring and evaluating patients' perceptions of changes in their physical appearance (15). Awareness of one's body is influenced by a non-judgmental attitude toward failures, known as self-compassion. Self-compassion involves caring for oneself, adopting a non-judgmental perspective, and demonstrating empathy during times of suffering (16). It is associated with less suffering, better mental health, and higher life satisfaction (17). Additionally, self-compassion plays a crucial role in reducing sexual distress and enhancing sexual satisfaction in women (18).

In a study conducted by Michael et al., the results indicated that both self-compassion and damaged body image were associated with higher levels of sexual distress in cancer patients. Thus, as self-compassion decreased and damaged body image increased, the level of sexual distress also increased (6). Fischer et al. found that difficulties in emotion regulation were associated with lower sexual health, problems in the sexual cycle, and reduced sexual satisfaction (19). Additionally, a study by Yousaf et al. demonstrated that body image and self-compassion significantly predicted sexual distress in women after mastectomy (14).

A better understanding of the causes and factors associated with sexual distress may assist therapists in designing appropriate treatments for these patients. In a study conducted in Iran by Bagheri-Sheykhangafshe et al., results showed that a self-compassion-based treatment led to significant improvement in sexual function in MS patients (20). Another study by Fischer et al. indicated that internet-based therapy focusing on emotion regulation could improve sexual health in various aspects (21). Despite these findings, the studies had significant limitations, including a small sample size of mastectomy patients and sample selection based solely on breast cancer, without consideration of the type of surgery. Another important challenge was the culturally based nature of self-compassion, which is influenced by cultural values. This issue has significant implications because the results from one society cannot necessarily be generalized to another. Furthermore, these studies have inadequately focused on the role of mediators and have seldom used structural equation modeling from an analytical perspective.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to predict sexual distress based on self-compassion and the mediating roles of body image and the ability to regulate emotions in women with a history of mastectomy.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

The sample size was calculated using the SOPER formula, considering the number of latent and observed variables (4 and 14, respectively) (22). Based on an anticipated effect size of 0.19, a desired statistical power level of 0.80, a probability level of 0.05, and the number of latent and observable variables, the sample size was calculated to be 138 people (22). Additionally, according to Bentler's formula, which recommends 10 participants per indicator, the sample size for this study with 14 indicators was 140 people (23). However, accounting for an attrition rate, this number was increased to 163 people. The statistical population included all patients with breast cancer in Tehran who had undergone a mastectomy. Patients were selected from Hazrat Rasool Akram, Bazarganan, and Tarbiat Modares Hospitals and the Sepid psychotherapy clinic in Tehran using a purposive sampling method. Three patients were excluded from the analysis due to incomplete responses, resulting in a final sample size of 160 people.

3.2. Tools

3.2.1. Demographic Information

The demographic information collected in this study includes age, marital status, employment status, and education status.

3.2.2. Body Image Scale

This scale, developed by Hopwood et al., comprises 10 items designed to measure affective problems (feelings of self-awareness), behavioral problems (difficulty looking at one's naked body), and cognitive problems such as satisfaction with physical appearance. It is tailored for cancer patients and is applicable to individuals with any type of cancer or treatment. Responses are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (not at all = 0, very much = 3). The minimum and maximum scores for this scale range from 0 to 30, respectively, with higher scores indicating greater concerns about body image (15). Rajabi et al. confirmed the one-factor model of the Body Image Scale (BIS). Additionally, its Cronbach's alpha coefficient is at an acceptable level (0.70), and in relation to the Rosenberg self-esteem scale, the coefficient of its discriminant validity is significant (r = -0.21, P < 0.001) (24).

3.2.3. Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R)

Derogatis developed a 13-item scale to assess women's sexual distress. Items on this scale are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The total score of this scale, which ranges from 0 to 52, is calculated by summing the scores of all items. A higher score indicates more distress related to sexual desire. This scale demonstrates good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86) and test-retest reliability (0.74), and it can significantly differentiate between women with sexual dysfunction and those with normal sexual function, thereby showing adequate incremental validity. Ghassami et al. examined the psychometric properties of this scale in Iran. Its test-retest reliability and convergent validity were reported as 0.86 and 0.64, respectively (25).

3.2.4. Self-compassion Scale (SCS)

Neff developed a 26-item scale to measure self-compassion, featuring six subscales representing the main components of self-compassion in three contrasting pairs: Self-kindness (5 items), self-judgment (5 items), common humanity (4 items), isolation (4 items), mindfulness (4 items), and over-identification (4 items). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Subscale scores are obtained by summing relevant items, and the total score is derived by summing all items, with scores for the negative subscales (self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification) being reversed. A higher self-compassion score indicates better self-compassion. The internal consistency for this scale is robust, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92. Azizi et al. evaluated the validity and reliability of the Iranian version of this scale. The overall Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78, and its convergent validity was 0.26 (P < 0.05) (26).

3.2.5. Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)

This scale, designed by Gratz and Roemer, consists of 36 items. Responses are scored on a five-point Likert scale. Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale includes five subscales: Non-acceptance, Goals, Lack of Control, Awareness, Strategies, and Clarity. Its reliability was confirmed through a test-retest method, resulting in a coefficient of 0.88. A higher score indicates greater difficulty in emotion regulation, suggesting more emotional problems (27). Mazaheri investigated the psychometric properties of the Persian version of DERS. Convergent validity and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the entire scale were 0.35 and 0.82, respectively (28).

3.3. Procedure

To achieve the goals of this study, a descriptive and correlational study was conducted in 2022 - 2023. Sampling was done both online (Online form) and in person. For patients requesting a survey link, an informed consent form was provided and completed before sending the link. Thus, patients who had a smartphone received the link to the online questionnaires, while those without smartphones were provided with a paper-pencil version during their follow-up checkups. Patients who referred to the psychotherapy clinic had not started psychotherapy. Inclusion criteria for the study included being able to understand the questions, having a history of breast cancer and mastectomy, no substance abuse, no psychotherapy, no history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorders based on consultations with a psychiatrist, not using psychiatric medications, consenting to participate in research, and no cancer recurrence. Exclusion criteria included taking psychiatric medication, substance abuse, and receiving psychotherapy.

3.4. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Sanandaj Azad University with the code IR.IAU.SDJ.REC.1401.020. To address ethical considerations, all participants' personal information was kept confidential. They were required to fill out an informed consent form before completing the questionnaires.

3.5. Statistics

The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationships between variables, and structural equation modeling was employed to test the direct and indirect effects among the variables. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 25 and R software. Significance levels were set at P < 0.01 and P < 0.05. Data normality was evaluated and reported using skewness and kurtosis.

4. Results

The average age of the patients was 46.05 years. Other demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | Values a |

|---|---|

| Marital status | |

| Married | 134 (83.75) |

| Single | 26 (16.25) |

| Education | |

| Diploma or below | 53 (33.12) |

| Bachelor's degree | 61 (38.12) |

| Master's degree | 29 (18.13) |

| Doctoral degree | 17 (10.62) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 41 (25.62) |

| Housekeeper | 119 (74.38) |

Demographic Characteristics of the Subjects

The correlations between the study variables are reported in Table 2. The results of the correlation analysis indicated significant correlations between the total score of self-compassion and the total scores of body image disorder, difficulties in emotion regulation, and sexual distress, which were -0.54, -0.59, and -0.67, respectively (P < 0.01). Additionally, the correlations between difficulties in emotion regulation and body image with sexual distress were 0.64 and 0.69, respectively (P < 0.01). Therefore, the suitability of the model was confirmed.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-kindness | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Self-judgement | 0.30 a | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Human commonality | 0.26 a | 0.38 a | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Isolation | 0.26 a | 0.38 a | 0.99 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Mindfulness | 0.18 b | 0.25 a | 0.17 b | 0.25 a | 1 | |||||||||||

| Over-identification | 0.27 a | 0.44 a | 0.28 a | 0.26 a | 0.29 a | 1 | ||||||||||

| Self-compassion | 0.61 a | 0.74 a | 0.58 a | 0.60 a | 0.56 a | -0.66 a | 1 | |||||||||

| Body image | -0.23 a | -0.31 a | -0.28 a | -0.41 a | -0.32 a | -0.49 a | -0.54 a | 1 | ||||||||

| Nonacceptance | -0.38 a | -0.32 a | -0.15 b | -0.34 a | -0.30 a | -0.37 a | -0.49 a | 0.36 a | 1 | |||||||

| Goal-directed behavior | -0.34 a | -0.28 | -0.31 a | -0.26 a | -0.24 a | -0.42 a | -0.49 a | 0.30 a | 0.62 a | 1 | ||||||

| impulse control | -0.30 a | -0.31 a | -0.27 a | -0.31 a | -0.26 a | -0.36 a | -0.48 a | 0.35 a | 0.66 a | 0.65 a | 1 | |||||

| Awareness | -0.23 a | -0.24 a | -0.26 a | -0.15 b | -0.29 a | -0.33 a | -0.40 a | -0.34 a | 0.60 a | 0.56 a | 0.61 a | 1 | ||||

| Limited access | -0.35 a | -0.36 a | -0.34 a | -0.42 a | -0.33 a | -0.43 a | -0.59 a | 0.40 a | 0.68 a | 0.59 a | 0.72 a | 0.57 a | 1 | |||

| Clarity | -0.34 a | 0.25 a | -0.23 a | -0.30 a | -0.32 a | -0.32 a | -0.47 a | 0.33 a | 0.59 a | 0.50 a | 0.62 a | 0.54 a | 0.65 a | 1 | ||

| Emotion regulation | -0.39 a | -0.36 a | -0.32 a | -0.37 a | -0.35 a | -0.45 a | -0.59 a | 0.43 a | 0.84 b | 0.77 a | 0.87 a | 0.77 a | 0.87 a | 0.78 a | 1 | |

| Sexual distress | -0.41 a | -0.39 a | -0.39 a | -0.48 a | -0.36 a | -0.51 a | -0.67 a | 0.69 a | 0.53 a | 0.47 a | 0.52 a | 0.49 a | 0.60 a | 0.52 a | 0.64a | 1 |

The results of Pearson Correlation among Self-compassion, Difficulty in Emotion Regulation, Body Image, and Sexual Distress

After conducting a descriptive analysis, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to assess the relationships between variables. Prior to presenting the results, the assumptions necessary for SEM were verified. The multicollinearity of the variables was examined using tolerance and the variance inflation factor (VIF), which indicated an absence of multicollinearity. Additionally, kurtosis and skewness assessments confirmed the normality of the data, as shown in Table 3.

| Variables | Skewness | Kurtosis | VIF | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-compassion | -0.078 | 0.292 | 1.85 | 0.540 |

| Body image | -0.090 | 0.258 | 1.45 | 0.688 |

| DERS | 0.322 | -0.254 | 1.59 | 0.626 |

| Sexual distress | -0.119 | -0.264 |

The Results of Skewness, Kurtosis, VIF, and Tolerance

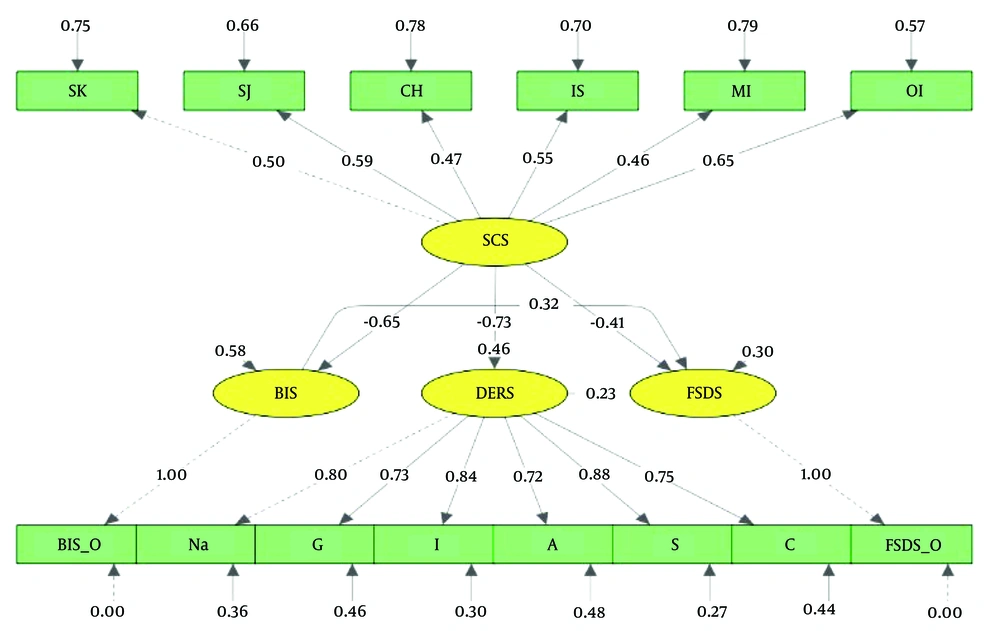

Structural equation modeling was utilized to explore the relationships among self-compassion, body image, difficulty in regulating emotions, and sexual distress. Figure 1 illustrates the results of the SEM, and Table 3 details the fit indices of the final model in the sample.

The conceptual model of the research, including the standardized regression coefficients. Key variables are labeled as follows: SK, self-kindness, SJ, self-judgment, CH, common-humanity, IS, isolation, MI, mindfulness, OI, over identification, SCS, self-compassion Scale, BIS, Body Image Scale, DERS, Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale, Na, non-acceptance, G, goals, I, irritability, A, awareness, S, strategies, C, clarity, FSDS, Female Sexual Distress Scale.

As shown in Table 4, the fit indices of the final model, including the comparative fit index (CFI = 0.93), goodness of fit index (GFI = 0.93), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI = 0.90), incremental fit index (IFI = 0.98), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.037), indicate a good model fit, thereby demonstrating the model's robustness. In Table 4, the fit indices of the final model comprised with acceptable level fit indices (29).

| Fit Index | DF | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | IFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptable level | + | < 0.08 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 |

| Final model | 74 | 0.037 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.93 |

Fit Indices of the Model

Furthermore, the direct standardized coefficients are detailed in Table 5. Results indicate that the direct effects of self-compassion on sexual distress, body image, and emotion regulation were -0.41, -0.65, and -0.73, respectively. Other direct effects are also reported.

| Path | Standardized Coefficients | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Self-compassion → difficulty in emotions regulation | -0.75 | 0.001 |

| Self-compassion → body image | -0.65 | 0.001 |

| Self-compassion → sexual distress | -0.41 | 0.001 |

| Body image → sexual distress | 0.32 | 0.001 |

| Difficulty in emotions regulation → sexual distress | 0.23 | 0.001 |

Results of Direct Relationships

Moreover, the indirect effect of self-compassion on sexual distress, mediated by body image, was statistically significant (-0.61). The indirect standardized coefficient of self-compassion impacting sexual distress, mediated by difficulty in emotion regulation, was also significant at -0.41. These results are summarized in Table 6.

| Path Direction | Standardized Coefficients | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Self-compassion → body Image → sexual distress | -0.61 | 0.001 |

| Self-compassion → difficulty in emotions regulation → sexual distress | - 0.41 | 0.001 |

Results of Indirect Relationships

5. Discussion

This study aimed to predict sexual distress based on self-compassion, with the mediating roles of emotion regulation and body image in women who have undergone mastectomy. A significant finding is that body image substantially relates to and can predict sexual distress in these women. This aligns with research indicating a link between body image and sexual distress in patients with mastectomy (14) and individuals with endometriosis (30).

It is reasoned that since the body significantly contributes to a partner's attractiveness, negative self-perception can lead to diminished self-esteem and a tendency to withdraw socially (31). Consequently, affected women may experience impaired sexual function and heightened concerns about it. Additionally, the breasts are closely tied to body satisfaction; many women seek breast enhancements to improve their body image and overall well-being, significantly impacting their sexual life (32).

Moreover, women may develop a negative body image after experiencing bodily changes, often obsessing over their appearance (12, 33), which could lead to increased sexual concerns. Breasts are also viewed as symbols of femininity (34) and are integral to sexual attractiveness, valued by both men (35) and women (36). Thus, alterations due to surgery can be perceived as a loss of wholeness and sexual appeal (13).

Another finding of this study is that difficulty in regulating emotions leads to increased sexual distress in women who have undergone breast surgery, aligning with previous research (37, 38). Women who undergo mastectomy often face significant emotional challenges due to the disease and the changes it imposes on their lives (39). These emotional disturbances can disrupt the natural process of sexual desire as symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and stress correlate with decreased sexual desire, avoidance of intimate contact, and concerns about sexual performance (38). Poor regulation of negative emotions adversely affects the initiation and maintenance of goal-directed behaviors (40), impairing relationships and sexual interactions with partners.

Additionally, the study reveals that self-compassion can predict sexual distress through body image as a mediating factor in women who have undergone mastectomy. This result is consistent with research demonstrating a connection between self-compassion, body image, and sexual distress (6, 30). Low self-compassion may hinder adaptation to surgical changes, leading individuals to perceive themselves as physically flawed. This perception can result in significant distress concerning their sexual needs due to feelings of shame about their appearance (6). Furthermore, societal stereotypes that emphasize physical perfection can exacerbate negative self-perceptions, particularly after surgical alterations that affect appearance (41). Thus, women may view themselves as sexually unappealing. Conversely, high self-compassion involves acceptance and self-care under any circumstances, whereas low self-compassion fosters a critical and judgmental view of one's appearance (42). This negative self-view enhances anxiety about sexual activities.

The final finding of this study was that self-compassion predicted sexual distress with the mediating role of difficulty in regulating emotions in women who had undergone breast surgery. Low self-compassion leads to the development of maladaptive strategies such as avoidance and denial, which reduce one's ability to tolerate and process negative emotions (43). This disruption impacts the natural process of sexual desire, which requires a degree of mental relaxation. Effective management of emotions like anxiety, stress, and depression requires self-esteem and self-compassion. However, with low self-compassion, women are unable to manage their emotions effectively, resulting in severe psychological distress related to sexual issues.

5.1. Conclusions

Self-compassion acts as a protective factor against the effects of mastectomy in women with breast cancer. These individuals typically adopt a non-judgmental and empathetic perspective toward changes in appearance caused by the disease, thereby experiencing lower sexual distress. Furthermore, these women demonstrate high resilience to negative emotions and can effectively control emotions that may lead to sexual stress. Therefore, to treat sexual distress in women with breast cancer, psychotherapists are advised to employ approaches such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which emphasizes self-compassion.

5.2. Limitations

Despite the insights provided by this study, it has notable limitations that must be acknowledged. Firstly, the study is cross-sectional and included only patients who had undergone a mastectomy, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Future research should adopt longitudinal methods and include diverse patient groups across both genders to enhance the applicability of the results.