1. Background

Health debates often focus on the concept of access to healthcare, frequently mentioned in discussions about universal health care or to highlight the inadequacies that prevent it (1). Regardless of whether a country is poor or rich, poverty and inequality are among the main causes of inadequate healthcare (2). The issue of social health disparities, traditionally viewed through the lens of access to care, is increasingly being emphasized in the management of chronic diseases like diabetes (3). Diabetes and its complications have significant care, follow-up, and monitoring requirements (4). Diabetes heavily affects Morocco, where, according to the World Health Organization's 2021 estimations, the prevalence rate of diabetes among adults is 12.4%, and the disease causes more than 12,000 deaths annually (5).

Poverty makes it more difficult to receive adequate healthcare. Furthermore, the location of medical institutions, the means required to get there, and even being aware of their presence can influence people's capacity to obtain medical treatment (6). Limited or delayed access to care can lead to increased morbidity and mortality rates (7). Society's poverty-stricken and vulnerable members often have limited access to healthcare (8). The Global Monitoring Report, "Tracking Universal Health Coverage 2017," shows that at least half of the world's population is still unable to access basic health care services. Additionally, rising healthcare costs result in nearly 100 million individuals falling into extreme poverty annually (9). In Morocco, patients are required to pay 50% of their healthcare costs. This substantial contribution significantly impacts vulnerable individuals (10).

Various initiatives aim to improve access to healthcare for the extremely poor and better coordinate existing systems (11). Therefore, to achieve this result, Morocco, a middle-income country, must have the necessary resources and mechanisms available. In fact, Morocco launched an initiative to ensure the generalization of the medical assistance system (dubbed Ramed) in favor of poor individuals. However, the initiative did not yield the desired results (12), with significant weaknesses, particularly regarding the continuation of service payments by households (13). As a result, the Moroccan government recently launched a new social protection project in December 2022, focusing on achieving universal medical coverage. However, this raises the question: Does access to health care depend solely on resolving the issue of medical coverage?

Certainly, Morocco has made genuine efforts to facilitate access to treatment for diabetic patients. Although community-based care has improved access to medical treatment for diabetic patients, it does not guarantee access to appropriate care (2). Improving the response to the medical needs of the poor is challenging due to the lack of data on their health status and use of health care services (14). Several studies have indicated a correlation between poverty and difficulties in accessing health care. However, it is crucial to delve deeper into the subject and understand the nature of these barriers qualitatively by examining the lived experiences of patients.

2. Objectives

This study was, therefore, designed to explore these barriers to health care access for poor diabetic patients in Morocco. A deeper understanding of the obstacles encountered by impoverished diabetes patients in accessing healthcare can guide the development of more effective interventions and strategies to tackle this issue.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This was a qualitative, descriptive, and phenomenological study aimed at describing the difficulties of accessing healthcare for diabetic patients living in poverty. Phenomenology is a study method that uses an inductive approach to explore and characterize experiences from the perspectives of those who have lived them. The goal is to understand and interpret lived experiences and transform them into explicit knowledge (15, 16).

3.2. Participants and Sampling

The study focused on poor diabetic patients who receive care at the Souss Massa regional hospital in Morocco. Non-probability purposive sampling was used to select patients. The inclusion criteria were: Diabetic patients living in poverty, as defined by the income criterion set by the High Commission for Planning (HCP) of Morocco at 50% of median household income (17), having type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and being aged 18 years or older. Exclusion criteria included women with gestational diabetes, diabetic patients with a mental illness that limits their intellectual capacity, and diabetic patients of foreign nationalities.

In qualitative research, the number of participants is rarely determined in advance, as statistical representativeness is not the aim (18). Instead, the sample size is determined by the theoretical saturation of the data. According to Savoie-Zajc, saturation occurs when new data no longer provides new information to understand the phenomenon being studied (19). Our study concluded with a sample size of 20 participants, which is typical for this type of study.

3.3. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by myself (A.E) between June and October 2023 with the target population. The interviews took place in a private and quiet room in various hospital departments where we met with the diabetic patients. These interviews were guided by an interview guide that included a list of open-ended questions related to the themes to be covered during the discussion (20).

A categorical framework, defined a priori in relation to the existing literature, facilitated the development of this interview guide. The framework included contextual barriers, barriers related to healthcare institutions, and patient-related barriers. During each interview, participants were first asked about their demographic and clinical characteristics using a questionnaire. This was followed by more specific questions related to the barriers they face in accessing healthcare, such as:

- “To what extent do the geographical and environmental conditions in your area impede your access to healthcare? How?”

- “What difficulties did you face in accessing healthcare related to health institutions during your experience managing your illness?”

- “In relation to your personal circumstances, what difficulties do you encounter in accessing care during your treatment and care experience?”

- “Is there any other information you want to share with me?”

The interviewer explained the questions further by asking probing questions like, "Could you give us an example of this or provide more information?"

The guide was created in the Moroccan Arabic dialect. Following the approval of the research authors, the guide was tested with the target sample for final validation. All interviews were structured and conducted in a similar manner. Interview data were recorded manually or using a tape recorder, depending on the participant's preference, after obtaining patient consent. Facial expressions were also evaluated and recorded. Each interview took approximately 30-40 minutes to complete.

3.4. Data Analysis

The data gathered from the interviews were evaluated using the qualitative content analysis method, which aims to organize and make sense of the data while drawing reasonable conclusions (21).

Two researchers independently analyzed the data manually. The transcripts were read multiple times to gain a general understanding of the content, and relevant statements about the phenomenon were extracted. In the subsequent steps, codes and categories were structured. The categorization and coding process were facilitated by the fact that the participants' opinions were quite similar.

After each researcher reviewed the responses and independently created their data analysis, the two analysts met to discuss their findings. During this discussion, each person described their organizational coding method, and a consensus was reached on how to name each entity and categorize the types of comments that fell into each category (22).

3.5. Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was ensured using Guba and Lincoln’s 1985 criteria of credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability (23, 24). Credibility was established through the interview guide test, extended engagement, interviewing process and techniques, field experience, and familiarity with the phenomenon and study context. Dependability was achieved by providing a detailed description of the study procedures, using appropriate data collection methods, employing a sampling strategy, selecting appropriate meaning units, and having the results examined by two researchers from outside the study. Transferability was ensured by providing a detailed description of the data collection, analysis techniques, and conclusions, enabling readers to apply the findings to their own circumstances. To enhance confirmability, the researchers discussed their reflexivity and engaged in peer debriefing, a method for reviewing interpretations and findings while minimizing researcher bias.

3.6. Ethics and Consent to Participate

Free and informed consent was obtained from participants after the interviewer explained the objectives and voluntary nature of the study. Participants were informed that they had complete freedom to leave the interview at any time and were assured that their personal information would remain confidential and anonymous. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Rabat, Mohammed V University (File number 16/23).

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants

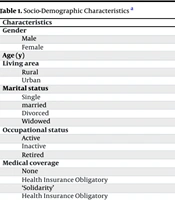

In total, we interviewed 20 diabetic patients living in poverty. Based on the analysis, there were twelve males and eight females. The mean age of the patients was 58.5 ± 17.1 years, with ages ranging from 23 to 83 years. Fourteen patients were from urban areas, and more than half (12 patients) were unschooled. Most of the sample (15 patients) were unemployed. The majority (16 patients) had type 1 diabetes, and 15 patients had complications related to diabetes (Tables 1 and 2).

| Characteristics | Participants; (n = 20) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 12 (60) |

| Female | 8 (40) |

| Age (y) | 58.5 ± 17.1 |

| Living area | |

| Rural | 6 (30) |

| Urban | 14 (70) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 4 (20) |

| married | 12 (60) |

| Divorced | 1 (5) |

| Widowed | 3 (15) |

| Occupational status | |

| Active | 3 (15) |

| Inactive | 15 (75) |

| Retired | 2 (10) |

| Medical coverage | |

| None | 5 (25) |

| Health Insurance Obligatory ‘Solidarity’ | 8 (40) |

| Health Insurance Obligatory | 7 (35) |

| Level of education | |

| Unschooled | 12 (60) |

| Primary school | 5 (25) |

| Secondary school | 2 (10) |

| University | 1 (5) |

Socio-Demographic Characteristics a

4.2. Barriers to Accessing Healthcare

Access to medical services is unequal among different classes of the population (25). Table 3 summarizes the themes, categories, and codes extracted from the analysis of the results of this study.

| Themes | Categories | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual barriers | -Geographical location | Distance, remoteness; rural area |

| -Transportation problems | Accessibility and availability; type of transportation; travel time | |

| Barriers related to the healthcare institutions | - The lack of equipment and medication | Limited access; logistical issues; stockout |

| - Healthcare providers staff shortages | Doctors’ shortage | |

| - Functioning difficulties | Insurance inefficiency; complexity of care pathway; appointments delays | |

| Patient-related barriers | -Lack of financial resources | High out of pocket; poverty; expensive costs |

| - Cultural difficulties | Health and illness as predestined fate; gender approach | |

| -Patient/caregiver relationship | Poor communication; poor understanding of patients’ needs; language barriers |

Themes, Categories and Codes

4.2.1. Theme 1: Contextual Barriers

This theme is divided into two categories: (a) geographical location and (b) transportation problems.

4.2.1.1. Geographical Location

In Morocco, access to healthcare is unequal, with a significant disparity between urban and rural areas. The users interviewed, primarily those from rural areas, reported suffering due to the long distances and extended journeys required to reach hospitals and health centers. This issue is particularly challenging, as constant medical supervision is essential for the care of diabetic patients in deteriorating conditions.

“I live in a rural area. To get here, I have to drive for at least 4 hours. The health center is also a long way away, and now that I'm discharged, I'll need someone to take care of my foot. What should I do? (with sadness)” (Patient 1).

“The hospital is quite distant, so we only visit for emergencies. This time, due to the severity of my condition, I came with the community ambulance” (Patient 8).

4.2.1.2. Transportation Problems

The shortage or unavailability of transportation can exacerbate geographic challenges. This study suggests that patients from rural areas often face difficulties with public transportation.

“In order to get to the hospital, I have to walk part of the way to the weekly market. That's where I wait for transportation, but it's not guaranteed that I will find one in a timely manner; it is not a public transportation system. In my case, I am unable to walk for long periods of time” (Patient 15).

“There is a significant issue with remoteness; transportation is not readily available in the area where we live. There are no buses available, only taxis, which are also scarce. Most of the time, we hitchhike” (Patient 10).

4.2.2. Theme 2: Barriers Related to Healthcare Institutions

The healthcare system is a key factor in determining healthcare utilization. This theme consists of three categories: (a) lack of equipment and medication, (b) staffing shortages, and (c) functioning difficulties.

4.2.2.1. Lack of Equipment and Medication

Based on the survey results, a significant number of patients reported facing a lack of equipment, materials, and treatments during their visits to healthcare facilities (health centers and hospitals).

“Often, there is a shortage of blood glucose test strips. Getting tested at the pharmacy will cost 20 dirhams; even the blood pressure monitor is reported to be broken down. (…)” (Patient 9).

“However, stockouts of oral treatments still occur.” (Patient 8).

The lack of equipment, particularly in medical imaging, and the unavailability of certain medical tests are also significant issues: “They asked me to do a private scan because there was a problem with the hospital one. Due to a lack of resources, I am still looking for a solution.” (Patient 14).

“The doctor requested additional tests, which depleted all my savings in the private healthcare sector. I am still on my way to the private laboratory for more tests. (with astonishment)” (Patient 9).

4.2.2.2. Healthcare Provider Staff Shortages

Staffing shortages in public institutions also pose a problem that affects access to healthcare for poor patients, as illustrated by the following statements: “In our neighborhood, there is only one doctor attending to a fairly large population. Every morning, an unlimited queue forms. As a diabetic, it is important to avoid going without food or insulin for long periods, which is why I don't get checked regularly” (Patient 4).

“At the provincial hospital in our locality, we do not have all the specialists we need. The patients are often referred to the larger hospital in Agadir” (Patient 13).

4.2.2.3. Functioning Difficulties

One of the barriers is the upfront payment for services, especially with insurance inefficiency (recovery and eligibility conditions). Currently, poor patients, whether they have medical coverage or not, are facing this issue. During this transition period to the new mandatory health insurance reform, "AMO Tadamon," individuals with expired Ramed cards who haven't yet switched coverage will encounter problems. Additionally, those without medical coverage or whose insurance has lapsed due to job loss will also face difficulties. As illustrated by the patients: “I've been waiting a few months to sort out my 'Health Insurance Solidarity’ situation. They told me I had exceeded the threshold for the poor category when we don't have the resources. And the worst thing now is, who’s going to pay for these hospital services?” (Patient 9). “Even with my mutual insurance, there are problems at the hospital. Apart from hospitalization, all examinations have to be paid for in advance. I have already sent the previous file, and I am still waiting for a response.” (Patient 3).

Moreover, regarding the transition to private institutions, the situation for the poor remains delicate: “Yes, now with this change, this card ‘Health Insurance Solidarity’ is also valid for the private sector, but I have to pay before the care. Why not have free access like in the hospital? (with sadness)” (Patient 19).

Secondly, there is the constraint of having to follow a designated care pathway, even though it was established to organize the flow of care between different health departments. This can sometimes hinder care for poor people. Patients often express frustration when they have to go to great lengths and travel long distances to reach a health institution, only to be sent to another one. “They sent me from 'Ait Baha' to 'Biougra' and then they sent me here. Why does one send me to the other? Waste of money and time” (Patient 1).

“Once, I needed to be seen by a specialist in cardiology, and to see him, I needed a form or a paper from my doctor that I usually consult; I don't understand! I can't see any other doctors?” (Patient 16).

Thirdly, patients also express the obstacles associated with making appointments. Almost a third described their suffering from long periods of waiting for a scanner appointment and outpatient specialist consultations.

“If I want to see the specialist, I need 30 days, if not more. I got fed up and went to see a doctor in the private sector” (Patient 8).

“I need to have a scan. You can't imagine the delay!” (Patient 18).

In summary, these functioning difficulties can result in delayed or non-use of healthcare or referral to the private sector, which typically means increased costs for a poor population.

4.2.3. Theme 3: Patient-Related Barriers

This theme includes three categories:

4.2.3.1. Lack of Financial Resources

One of the most important and common limitations for study participants is economic constraint. All of the patients interviewed said they had suffered from the high costs associated with the disease, which included consultations and lifelong medication. The following quotes illustrate this: “The expenses are too much, out of measurement” (Patient 9).

“Apart from insulin, which is free, diabetes equals expenses” (Patient 4).

When they are unable to pay, some patients neglect to receive care: “My vision was at risk due to diabetes, and despite spending 1200 dirhams per laser treatment session, the doctor said I needed surgery. Unable to afford further expenses, my wife and I returned home” (Patient 8).

4.2.3.2. Cultural Difficulties

According to the report, cultural attitudes continue to be a barrier for people living in poverty. Although noted by a small number of participants, some individuals in this group believe that health and disease are predetermined and avoid seeking care if they feel the services are not worth the time or money: “My current condition of health is a destiny; it’s normal; God intended it for me. We have other responsibilities and needs. We cannot set aside everything for health” (Patient 19).

In addition to gender inequality limiting women's access to healthcare, their status as women has influenced their perception of health as a priority. Women's health in Morocco lags behind that of men due to socioeconomic constraints that limit women's standard of living: “Yes, I wasn't concerned about my health. I valued my children and family” (Patient 10).

“The woman is concerned about the guy when he is ill, but when a woman becomes ill, the man is unconcerned” (Patient 3).

4.2.3.3. Patient/Caregiver Relationship

A healthy patient-caregiver relationship fosters trust and encourages self-care. However, if this relationship is inadequate, it can impede access to necessary healthcare. Poor patients frequently receive substandard treatment and feel excluded compared to individuals with more financial resources. They describe having to repeatedly request or plead for the services and information they need: “Sometimes no one is there to greet or guide us, leaving us to find the information on our own” (Patient 12).

Language and communication problems can cause major disruptions in the treatment process, particularly for diabetics who require multidisciplinary care: “Some people speak to us in French, and we do not comprehend what they are saying” (Patient 1).

A lack of communication is also sometimes a barrier: “They don't say much—only a few questions and replies, followed by a prescription. When I left, I still had no idea what was wrong with my health or what the prescription was for” (Patient 3).

5. Discussion

The majority of studies conducted on access to healthcare focus on the barriers encountered by the general population without specifically addressing the poor population. Alternatively, they only address one dimension of these barriers.

In summary, the results of the present study reveal similarities with studies already conducted. As presented in this study, regarding contextual factors, geographical location is considered the main factor. The literature confirms that the distance between one's home and a health facility is a primary obstacle (26). This is a more serious problem in rural areas than in urban areas (27). In Morocco, geographically speaking, access to primary healthcare facilities remains very difficult for nearly 24% of the population (28). Since distance is a factor, transportation is necessary to reach the destination, presenting challenges related to accessibility, availability, and cost. Distant health centers increase travel time and costs, making healthcare difficult to access, especially for the poor (29). Similarly, the results of the panel survey by the national human rights observatory indicate that among the main reasons for not using healthcare services, the cost and inconvenience of transportation rank third among the 3rd, 4th, and 5th quintiles of the disadvantaged social categories of the Moroccan population (30).

Health institutions play a prominent role in patient healthcare utilization, affecting the use of healthcare services by poor patients in various dimensions. Regarding the lack of equipment, medication, and healthcare providers, the unavailability of these services affects patients' care-seeking behavior and negatively impacts effective diabetes management (31). According to the report of the Moroccan Economic, Social, and Environmental Council, stocking and distributing medication is a problem within the public sector, resulting in large quantities of expired medication, delayed deliveries, and frequent stock-outs (32). Studies have shown that most medical costs associated with diabetes are due to the treatment of complications (33). Consequently, patients may be asked to pay for their own medical treatment during hospitalization, particularly for medications not included in the hospital’s available list. As for medical scans and tests, a large proportion of specialist examinations are not carried out in prefectural or regional hospitals but rather in private sector hospitals (34). Therefore, if such an examination is required for continuing treatment, the patient will be obliged to seek them out in the private sector and return to the public sector to complete the rest of the treatment (13).

With regard to care providers, one of the main failures of the Moroccan health system is the shortage of human resources as well as the regional imbalance in their distribution. In Morocco, the density (per 10,000 population) is 7.3 for doctors (public and private) and 9.2 for nurses and health technicians, while the WHO recommends a critical limit of 44.5 doctors and nurses per 10,000 population to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (30). As a result, patients' commutes can be long, complex, and costly (32). In this sense, the principle of free healthcare for the poor is contradicted by the inadequacy of the medical system and the non-existence of an effective one (35).

Regarding the functioning of the healthcare system, the inefficiency of the health insurance system (recovery, partnership agreements, and eligibility conditions) affects access to care for poor patients. According to the internal regulations of Moroccan hospitals, if a patient is not affiliated with health insurance and has no medical condition justifying exemption under current regulations, they are required to pay the full cost of hospitalization based on the applicable rates (36). Having health insurance is meant to provide reassurance and relief from the financial burdens of health expenditures (37). However, even with health coverage, poor patients report difficulties in using private care that requires payment in advance or copayments. It is noted that copayments are higher in the private sector than in the public sector, with diabetes care in the private sector being 51% more expensive than in the public sector (34).

Accessibility to a hospital also requires adherence to the care pathway. This means not going to the provincial or regional hospital unless referred by primary health center professionals and only seeking the services of a university hospital when referred by the provincial or regional hospital. Administrative constraints mainly involve submitting referral forms and making prior appointments for the requested service (35). Diabetic patients have expressed dissatisfaction with their healthcare pathways due to prolonged waiting times (31). The care pathway must be well-designed to adapt to the needs of the population and not create barriers to medical access. A necessary solution is to reinforce healthcare provision to enable local availability, so that patients do not have to travel long distances to receive a simple service (38).

Regarding patient-related barriers, financial accessibility of care is undoubtedly the main difficulty encountered by patients living in poverty. It is a significant barrier to diabetes management for patients from low socioeconomic backgrounds (39, 40). The ongoing expense of lifelong diabetes treatment puts a strain on household budgets, leading to extremely difficult decisions, such as choosing not to invest in the patient's treatment (41). Consequently, diabetics from poor households are six times more likely to be non-compliant with their treatment (42). Poverty was cited as the top reason by doctors in Morocco, with a percentage of 80%, for why patients do not complete the HbA1c tests requested during their follow-ups (43).

Cultural factors among patients are also influenced by poverty, affecting their perception of health as a priority. One of the main reasons why poor people do not seek healthcare regularly is a lower perceived risk of health problems (44). Health knowledge can affect the use of healthcare services to manage diabetes (45). In relation to the gender approach, as one of the dimensions of the cultural aspect, women depend more on others for decision-making regarding healthcare (46).

Moreover, the relationship between caregivers and patients is seen as a factor affecting poor people's access to healthcare. Previous studies have shown that good communication positively influences diabetes management (47, 48). Among the main barriers identified in a literature review by Lazar and Davenport is the distrust many low-income people have in healthcare providers (44). A Tunisian study found that diabetic patients mainly complain about unsatisfactory communication and medical information, as well as a lack of empathy and compassion from healthcare professionals (49). Poor patients express a sense of frustration and exclusion due to the inappropriate attitudes and behaviors observed among healthcare staff (50). The overwork of medical professionals could contribute to these attitudes. Therefore, the healthcare system urgently needs to increase the number of staff to improve the situation (51).

These results are significant both medically and socially. They provide a guide for further in-depth studies related to medical coverage for the poor and the inadequacies of healthcare provision for the vulnerable diabetic population.

5.1. Limitations of the Study

There are some limitations to this study. Firstly, patients were selected based on a single criterion of monetary destitution, and the sample size was relatively small. Additionally, the study’s location poses a constraint. While it is regional and serves a vast and diverse population, the study focused on only one context. Therefore, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to other healthcare environments.

5.2. Conclusions

Many barriers to accessing healthcare have been reported by poor diabetic patients. The main recommendations are as follows: Firstly, it is essential for health insurance organizations to review their agreements with public and private institutions regarding the payment of services. Secondly, public-sector facilities need to strengthen their infrastructure and medical equipment while also increasing the number of healthcare providers to ensure quality reception and treatment for all patients. Finally, it is crucial to focus on developing social strategies to combat healthcare access exclusion, particularly in rural areas. In general, promoting the use of healthcare requires comprehensive cooperation.