1. Background

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), collective violence refers to violent and aggressive behaviors carried out by a group of individuals against another group, encompassing physical, psychological, and social forms of violence (1, 2). The prevalence of collective violence is recognized as a significant social and health issue worldwide, including in Iran (1). Globally, collective violence is particularly widespread in high-tension regions such as the Middle East and Africa, where it is driven by factors such as economic inequalities, ethnic and religious conflicts, and resource shortages (3-5). In Iran, statistics from the Forensic Medicine Organization indicate that street and family disputes account for a substantial portion of daily referrals to forensic centers. For example, in 2021, more than 586,000 cases of disputes were reported to forensic centers, underscoring rising social tensions and the need for preventive and educational interventions (1).

These conflicts are not limited to adults; they are also widely observed among students (6). Due to their developmental stage and heightened vulnerability, students are particularly at risk of engaging in or experiencing collective violence (7, 8). Educational settings, which should foster personal growth and development, sometimes become arenas for violence and conflict (9). Such violence can have profound negative effects on the psychological and social well-being of students (10).

Adolescence is a critical stage of development characterized by significant physical, emotional, and social changes (11). During this period, individuals are highly influenced by external factors such as peer pressure and family dynamics (12). The significance of adolescence lies in the formation of identity, moral values, and social relationships, which can have long-term implications for behavior and mental health (13). Understanding the impact of these factors during adolescence is essential for addressing issues such as collective violence, as interventions at this stage can lead to more effective and lasting outcomes (14).

In Iran, approximately 30% of the population is either suffering from or at risk of developing a mental health disorder, with a significant proportion of these individuals being adolescents (15). Studies have shown that high-risk behaviors such as substance abuse, smoking, and unsafe sexual practices are prevalent among Iranian teenagers, with around 18% of boys and 1.5% of girls engaging in high-risk behaviors (16). Approximately 4% of Iranian teenagers are involved in substance abuse, and 9% have experienced alcohol or cigarette use (17). Collective violence, particularly in educational and social settings, poses a serious threat to their mental and physical health (1).

Additionally, Iranian teenagers face significant challenges, including alcohol and drug abuse, mental health disorders, and exposure to violence. Recent reports have highlighted alarming incidents, such as the deliberate poisoning of schoolgirls and the deaths of children during protests, further exacerbating the dangers faced by teenagers in Iran (17, 18). These issues emphasize the urgent need for comprehensive strategies to protect and support Iranian teenagers.

Previous studies in Iran have primarily focused on the prevalence and contributing factors of collective violence among teenagers. For example, a study that validated the Multidimensional Scale of Acceptance of Collective Violence (MSACV) among teenagers in Tehran underscored the necessity of reliable tools to measure this phenomenon (1). However, there is a gap in the literature when comparing these findings with similar studies conducted in other countries. For instance, research in South Africa has revealed that violence is widespread among youth, particularly in low socio-economic neighborhoods (19). Similarly, studies in the United States have explored the impact of social and environmental factors on youth violence, emphasizing the roles of community and family dynamics (20). These international studies provide valuable insights that can help contextualize findings from Iranian research and highlight the need for cross-cultural comparisons to develop more effective interventions (1).

Collective violence among students is a significant and complex issue, with far-reaching effects on their mental and social well-being (6). Investigating this phenomenon is crucial due to its detrimental consequences for both students and society (21). Collective violence can lead to increased anxiety, depression, reduced self-esteem, and behavioral problems in students (22-24). Furthermore, it can disrupt students' social and academic relationships, resulting in lower academic performance and higher dropout rates (6, 25).

Previous research has shown that moral development (26-29), family relationships (27, 30-35), and peer relationships (33, 36-39) play critical roles in shaping violent behaviors among students. Peer relationships can serve as either a protective or risk factor (37). For example, peers who encourage violent behaviors can negatively influence students' actions (40). Conversely, healthy and supportive family relationships can help mitigate the tendency towards violence (34). Moral development also plays a vital role; students with strong moral values and principles are less likely to engage in violent behaviors (29).

Numerous studies have explored the role of psychological security in reducing collective violence (27, 41-44). These studies suggest that psychological security can serve as a protective factor, reducing the tendency toward risky behaviors (44). However, there remain several gaps in the existing research that require further exploration. For instance, many studies have investigated peer relationships, moral development, and family relationships in isolation, with less attention given to how these factors interact (27, 41-44).

Exposure to violence can result in a range of internalizing and externalizing outcomes (45). Internalizing outcomes include anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal, while externalizing outcomes involve aggressive and delinquent behaviors (46-48). Various models have been proposed to explain these associations. For example, the social learning theory suggests that individuals acquire violent behaviors through observing and imitating others, particularly in environments where violence is prevalent (49, 50). The ecological systems theory highlights the influence of different environmental layers, ranging from family and peer interactions to broader societal factors, in shaping an individual's response to violence (51, 52). Moreover, the general strain theory proposes that exposure to stressors, such as violence, can lead to negative emotions and maladaptive behaviors. Understanding these processes is critical for developing effective interventions to mitigate the harmful effects of violence on individuals (53, 54).

Current knowledge in this field points to the need for more comprehensive research that examines the complex interactions between various factors (27, 41-44). This study focuses on the mediating role of psychological security as a key factor, aiming to address the existing gaps in previous research and provide a more thorough examination of the relationships between peers, moral development, family relationships, and collective violence.

The practical application and significance of this study lie in its potential to guide educational policymakers and psychological counselors. By understanding the factors contributing to collective violence and the role of psychological security, this research can aid in developing targeted interventions and programs aimed at reducing violence in schools. These findings can help design educational and counseling programs that foster healthy peer and family relationships, promote moral development, and enhance psychological security among students. Ultimately, this study seeks to offer practical solutions for reducing collective violence and improving the psychological and social well-being of students, thereby contributing to a safer and more supportive educational environment (48).

The results of this study can be highly valuable for educational policymakers and psychological counselors. These findings can help enhance educational and counseling programs for students, offering effective strategies for reducing collective violence. Additionally, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of the relationships between the variables under study and may lead to the development of new theories in this field (55).

2. Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the impact of peer relationships, moral development, and family relationships on collective violence, with a focus on the mediating role of psychological security among male high school students in Mashhad. This research aimed to offer practical solutions for reducing collective violence and improving the psychological and social well-being of students.

2.1. Summary of Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: Higher levels of moral development will have a direct, significant negative impact on collective violence.

Reference: This hypothesis aligns with the findings of Nussio (2023), which suggest that moral beliefs play a critical role in preventing collective violence by promoting ethical reasoning and empathy (10).

Hypothesis 2: The quality of the relationship with the father will have a direct, significant negative impact on collective violence.

Reference: Solimannejad et al. highlight the importance of parental relationships, particularly with fathers, in reducing aggressive behaviors among Iranian male adolescents (27, 33).

Hypothesis 3: The quality of the relationship with the mother will have a direct, significant negative impact on collective violence.

Reference: Similar to the previous hypothesis, Navas-Martínez et al. emphasize that maternal attachments, through fostering emotional security, lower the likelihood of violence (35).

Hypothesis 4: Negative peer relationships will have a direct, significant positive impact on collective violence.

Reference: McCloskey and Stuewig demonstrate how poor peer relationships increase exposure to negative behaviors, subsequently escalating involvement in collective violence (36).

Hypothesis 5: Psychological security will have a significant negative impact on collective violence.

Reference: According to Mattaini, enhancing psychological security is fundamental in reducing the psychological drivers behind collective violence (44).

Hypothesis 6: Peer relationships will have a significant negative impact on collective violence through the mediating role of psychological security among male high school students.

Reference: Berkowitz and Winstok note that strong, positive peer relationships can enhance psychological security, mitigating the effects of collective violence (37).

Hypothesis 7: Moral development will have a significant negative impact on collective violence through the mediating role of psychological security among male high school students.

Reference: Hsu and Ouyang found that interventions promoting moral reasoning help foster psychological security, thereby reducing violent tendencies (29).

Hypothesis 8: Relationships with the father will have a significant negative impact on collective violence through the mediating role of psychological security among male high school students.

Reference: Labella and Masten argue that supportive paternal relationships contribute to a sense of security, reducing aggression (34).

Hypothesis 9: Relationships with the mother will have a significant negative impact on collective violence through the mediating role of psychological security among male high school students.

Reference: Zhou et al. explain that secure maternal relationships help develop resilience and psychological security, which in turn reduces violent behavior (33).

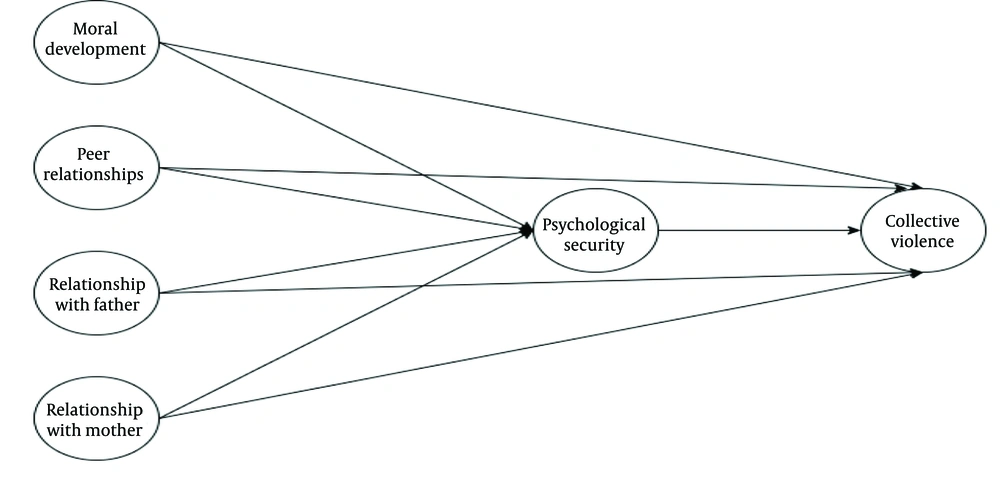

2.2. Conceptual Model

The conceptual model of this study illustrates the relationships between various variables. In this model, moral development, relationships with the father, relationships with the mother, and peer relationships are considered independent variables. Their impact on collective violence is examined through psychological security as a mediating variable. This model explores the complex interactions between these factors and their influence on collective violence (Figure 1).

3. Methods

This research is a correlational study that examined the relationships between various variables. The conceptual model investigates the impact of peer relationships, moral development, and family relationships on collective violence among male high school students in Mashhad. In this model, psychological security is considered an intermediary variable that plays a significant role in moderating and mediating the relationships between the independent variables (peer relationships, moral development, and family relationships) and the dependent variable (collective violence). This model allows researchers to comprehensively examine the direct and indirect effects of these variables on collective violence and analyze the mediating role of psychological security in these relationships.

3.1. Population, Sample Size, and Sampling Method

The statistical population of this study includes all male high school students (grades 10, 11, and 12) in Mashhad. This population encompasses male students from various high schools in the city, providing the diversity and breadth needed for a precise and comprehensive analysis of the relationships between peer relationships, moral development, family relationships, and collective violence.

To ensure the sample size is appropriate for an analytical study, a power analysis was conducted using G*Power software. This analysis considered a significance level of 0.05, a power of 0.80, and an effect size of 0.1. Based on these parameters, the required sample size was calculated to be approximately 787 participants, ensuring the detection of small-to-medium-sized effects. However, to improve the robustness and generalizability of the findings, the sample size was increased to 1300 participants through cluster sampling. This larger sample enhances the accuracy and validity of the results, particularly in examining the mediating role of psychological security (56).

This study employed cluster sampling, with the following steps: First, three educational districts in Mashhad (Districts 1, 3, and 5) were randomly selected. Then, six boys' high schools were randomly chosen from each district. Finally, three classes from grades 10, 11, and 12 were randomly selected from each high school. This cluster sampling method was chosen due to the geographical dispersion and diversity of students across districts, making it a suitable approach for this study. It provided access to a diverse and representative sample of the statistical population, enhancing the accuracy and validity of the research findings.

3.2. Data Collection Method

Data were collected through face-to-face interactions. The researcher personally distributed and collected the questionnaires from the students, ensuring that the participants fully understood the questions and provided accurate responses. This approach allowed the researcher to immediately address any questions or concerns raised by participants. Data collection took place between November 2023 and January 2024.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible participants were male high school students (grades 10 - 12) in Mashhad who attended the selected schools and provided written parental consent. Students who were willing to participate and completed the questionnaires were included. Exclusion criteria applied to students without parental consent, those unwilling to continue, or those with incomplete questionnaires, ensuring the accuracy and validity of the research.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration. Students and their parents or guardians provided verbal and written consent, respectively. Confidentiality was maintained, and participation was voluntary, with the option to withdraw at any time. The researcher personally distributed and collected the questionnaires, expressing gratitude to the participants by giving them a pen and notebook. A total of 1,211 questionnaires were collected (57).

3.5. Instruments

The Multidimensional Scale of Acceptance of Collective Violence (MSACV) consists of 21 questions rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 21 to 105. The scale includes six factors: Physical violence (items 1 - 3), verbal violence (items 13 - 15), isolation (items 10 - 12), indirect violence (items 16 - 18), attraction (items 4 - 6), neglect (items 7 - 9), and positive reactions (items 19 - 21). The validity and reliability of the scale were confirmed, with an overall Cronbach's alpha of 0.83 and factor alphas ranging from 0.52 to 0.88. In Iran, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.91 (1).

The Moral Development Questionnaire (MDQ) comprises 13 questions rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 13 to 65. It measures four dimensions: Social morality (items 1-4), individual morality (items 5 - 7), conventional morality (items 8 - 10), and pre-conventional morality (items 11 - 13). The validity of the scale was confirmed by expert review, and the Cronbach's alpha was reported at 0.93. Factor analysis demonstrated good fit (GFI = 0.98, AGFI = 0.97). In this study, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.89 (58).

Fine's Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire (FP-CRQ) contains 24 questions on a 7-point Likert scale. The scoring ranges from 15 to 105 for the father and 18 to 124 for the mother. The father section covers positive feelings, involvement, communication, and anger, while the mother section addresses positive feelings, role confusion, identity formation, and communication. Validity and reliability were confirmed, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.959 in Iran. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.81 (59).

The Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument (APRI) includes 36 questions on a 6-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 36 to 216. It assesses bullying and victimization, each with verbal, social, and physical subcomponents. The reliability coefficients ranged from 0.82 to 0.92. In Iran, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.94 overall, with 0.92 for the individual components. Factor analyses confirmed the scale's validity (60). In this study, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.93.

Maslow's Psychological Security Questionnaire (MPSQ) consists of 18 yes/no questions, with scores ranging from 0 to 18. It assesses self-confidence, dissatisfaction, environmental incompatibility, and perception by others. The reliability of the questionnaire was reported as 0.80, and its validity was confirmed by expert review. In this study, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.90 (61, 62).

3.6. Data Analysis Method

Statistical analyses were applied to examine the demographic characteristics and central and dispersion indices of the research variables, including measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode) and variability (standard deviation, variance). Frequency distributions and percentages were calculated for categorical variables.

For inferential statistics, path analysis was used to test the conceptual model and assess the direct and indirect relationships between variables. The analysis involved estimating the standardized regression coefficients (beta weights) for each path in the model. The statistical significance of the relationships was determined using p-values, with paths having a p-value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant, ensuring accuracy in the interpretation of the relationships.

Model fit was evaluated using several indices:

- Chi-square/Degrees of Freedom (CMIN/DF): A value less than 3 indicates a good fit.

- Goodness of Fit Index (GFI): Values close to 1 indicate a good fit.

- Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI): Values close to 1 indicate a good fit.

- Normed Fit Index (NFI): Values close to 1 indicate a good fit.

- Comparative Fit Index (CFI): Values close to 1 indicate a good fit.

- Incremental Fit Index (IFI): Values close to 1 indicate a good fit.

- Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI): Values close to 1 indicate a good fit.

- Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA): Values less than 0.08 indicate a good fit (63).

These methods ensured the accuracy and validity of the results, adhering to international scientific standards. The results of the path analysis were interpreted to understand the direct and indirect effects of peer relationships, moral development, and family relationships on collective violence, with psychological security as a mediating variable.

4. Results

Among the 1,211 fathers, the majority had a high school diploma (41.1%), followed by those with less than a high school diploma (14.2%) and bachelor's degrees (13.4%). Smaller percentages had associate degrees (11.4%), middle school education (8.2%), elementary school education (4.7%), higher than a bachelor's degree (4.0%), were literate (1.7%), or illiterate (1.4%). For the mothers, 38.6% had a high school diploma, 16.4% had a bachelor's degree, 10.2% had completed elementary school, 9.3% had less than a high school diploma, 8.2% had an associate degree, 6.4% had higher than a bachelor's degree, 5.9% had completed middle school, 3.1% were literate, and 1.8% were illiterate.

Regarding employment status, 71.1% of the fathers were employed, 17.9% were retired, 5.8% were deceased, and 5.2% were unemployed. For the mothers, 49.3% were employed, 30.9% were homemakers, 13.1% were retired, 3.6% were deceased, and 3.1% were unemployed. The average age of the students was 16.78 years with a standard deviation of 0.83 (Table 1).

| Category and Subcategory | Values a |

|---|---|

| Fathers' education | |

| High school diploma | 498 (41.1) |

| Less than high school diploma | 172 (14.2) |

| Bachelor's degree | 162 (13.4) |

| Associate degree | 138 (11.4) |

| Middle school | 99 (8.2) |

| Elementary school | 57 (4.7) |

| Higher than bachelor's degree | 48 (4.0) |

| Literate | 20 (1.7) |

| Illiterate | 17 (1.4) |

| Mothers' education | |

| High school diploma | 467 (38.6) |

| Bachelor's degree | 198 (16.4) |

| Elementary school | 124 (10.2) |

| Less than high school diploma | 113 (9.3) |

| Associate degree | 99 (8.2) |

| Higher than bachelor's degree | 78 (6.4) |

| Middle school | 72 (5.9) |

| Literate | 38 (3.1) |

| Illiterate | 22 (1.8) |

| Fathers' employment status | |

| Employed | 861 (71.1) |

| Retired | 217 (17.9) |

| Deceased | 70 (5.8) |

| Unemployed | 63 (5.2) |

| Mothers' employment status | |

| Employed | 597 (49.3) |

| Homemaker | 374 (30.9) |

| Retired | 159 (13.1) |

| Deceased | 44 (3.6) |

| Unemployed | 37 (3.1) |

| Students' mean age, (y) | 16.78 ± 0.83 |

Participants' Characteristics

The central tendency and dispersion indices of the main variables are presented in Table 2. The mean and standard deviation of the main variables are as follows: Collective violence had a mean of 32.55 and a standard deviation of 13.27; moral development had a mean of 32.84 and a standard deviation of 10.61; the relationship with the father had a mean of 19.46 and a standard deviation of 13.41; the relationship with the mother had a mean of 33.60 and a standard deviation of 16.56; peer relationships had a mean of 77.49 and a standard deviation of 31.26; and psychological security had a mean of 11.88 and a standard deviation of 5.98.

| Variables | Mean | Median | Mode | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical violence | 4.63 | 3 | 3 | 2.56 | 1.72 | 2.48 | 3 | 15 |

| Attraction | 4.61 | 3 | 3 | 2.51 | 1.72 | 2.54 | 3 | 15 |

| Neglect | 4.60 | 3 | 3 | 2.47 | 1.67 | 2.30 | 3 | 15 |

| Isolation | 4.68 | 3 | 3 | 2.52 | 1.66 | 2.47 | 3 | 15 |

| Verbal violence | 4.68 | 3 | 3 | 2.51 | 1.55 | 1.80 | 3 | 15 |

| Indirect violence | 4.67 | 3 | 3 | 2.52 | 1.60 | 1.99 | 3 | 15 |

| Positive reactions | 4.69 | 3 | 3 | 2.54 | 1.62 | 2.12 | 3 | 15 |

| Collective violence | 32.55 | 30 | 21 | 13.27 | 1.78 | 3.43 | 21 | 105 |

| Social morality | 8.69 | 8 | 12 | 3.69 | 0.14 | -0.83 | 4 | 20 |

| Individual morality | 6.53 | 6 | 9 | 2.77 | 0.13 | -0.86 | 3 | 15 |

| Conventional morality | 6.59 | 6 | 9 | 2.80 | 0.07 | -0.95 | 3 | 15 |

| Pre-conventional morality | 6.62 | 6 | 9 | 2.79 | 0.04 | -0.99 | 3 | 15 |

| Moral development | 32.84 | 32 | 45 | 10.61 | 0.05 | -0.24 | 15 | 75 |

| Positive emotions (father) | 5.28 | 4 | 4 | 4.58 | 0.86 | 0.47 | 0 | 24 |

| Father involvement | 7.63 | 6 | 6 | 6.52 | 0.86 | 0.47 | 0 | 30 |

| Communication (father) | 5.19 | 4 | 4 | 4.49 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0 | 28 |

| Anger (father) | 1.36 | 1 | 1 | 1.24 | 1.01 | 0.72 | 0 | 6 |

| Relationship with father | 19.46 | 16 | 15 | 13.41 | 0.96 | 1.25 | 0 | 75 |

| Positive emotions (mother) | 13.16 | 14 | 7 | 7.55 | 0.03 | -0.47 | 0 | 42 |

| Role confusion | 3.71 | 4 | 2 | 2.27 | 0.30 | -0.22 | 0 | 14 |

| Identity formation | 5.64 | 6 | 3 | 3.31 | 0.13 | -0.40 | 0 | 18 |

| Communication (mother) | 11.09 | 12 | 6 | 6.38 | 0.02 | -0.64 | 0 | 30 |

| Relationship with mother | 33.60 | 36 | 18 | 16.56 | -0.35 | 0.26 | 0 | 90 |

| Bullying | 38.86 | 37 | 54 | 16.19 | 0.16 | -0.40 | 18 | 108 |

| Victimization | 38.63 | 36 | 54 | 15.71 | 0.03 | -0.92 | 18 | 90 |

| Relationship with peers | 77.49 | 73 | 108 | 31.26 | 0.05 | -0.74 | 36 | 198 |

| Self-confidence | 4.64 | 7 | 7 | 2.98 | -0.71 | -1.28 | 0 | 7 |

| Dissatisfaction | 1.97 | 3 | 3 | 1.32 | -0.67 | -1.39 | 0 | 3 |

| Environmental incompatibility | 3.35 | 5 | 5 | 2.13 | -0.74 | -1.24 | 0 | 5 |

| People's perception | 1.92 | 3 | 3 | 1.33 | -0.59 | -1.49 | 0 | 3 |

| Psychological security | 11.88 | 13 | 18 | 5.98 | -0.77 | -0.51 | 0 | 18 |

Descriptive Statistics of Research Variables

The model fit indices for the conceptual model are shown in Table 3. The results indicate a near-perfect fit of the model to the data, with a CMIN/DF value of 0.01, significantly below the acceptable threshold of 3. The GFI and AGFI values are both 0.99, exceeding the acceptable fit criteria of 0.90 (64). Similarly, the NFI, CFI, and IFI values are 0.99, demonstrating a strong model fit (64). The PNFI is 0.99, which is well above the acceptable threshold of 0.50, and the RMSEA value of 0.001 is within the acceptable range of less than 0.08 (64). Together, these indices confirm that the proposed model fits the observed data extremely well.

| Results | CMIN/DF | GFI | AGFI | NFI | CFI | IFI | PNFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.001 |

| Acceptable fit | < 3 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.50 | < 0.08 |

Comparative Fit Indices

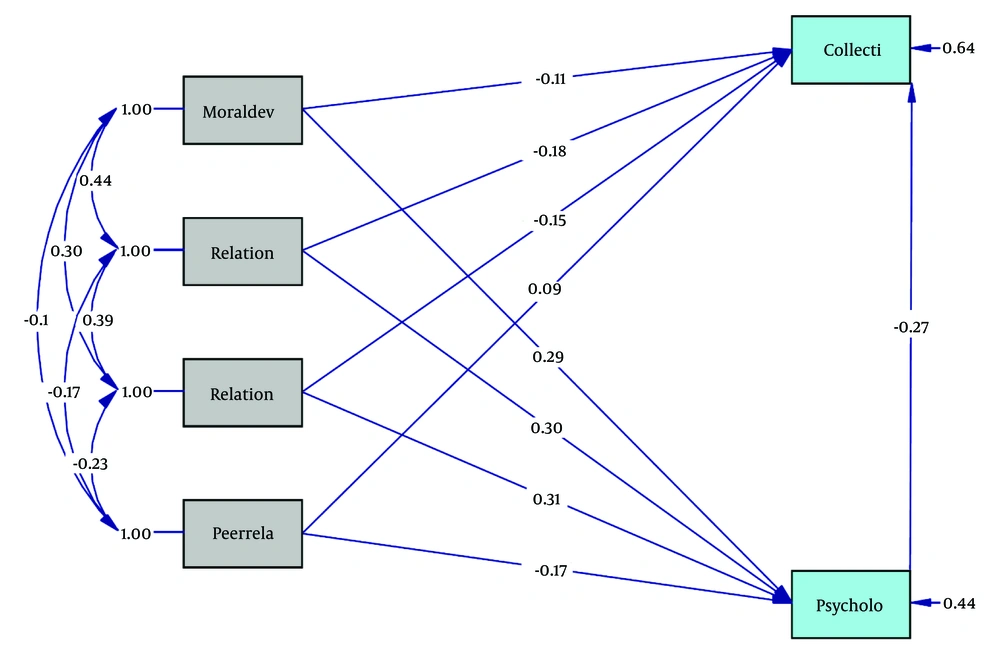

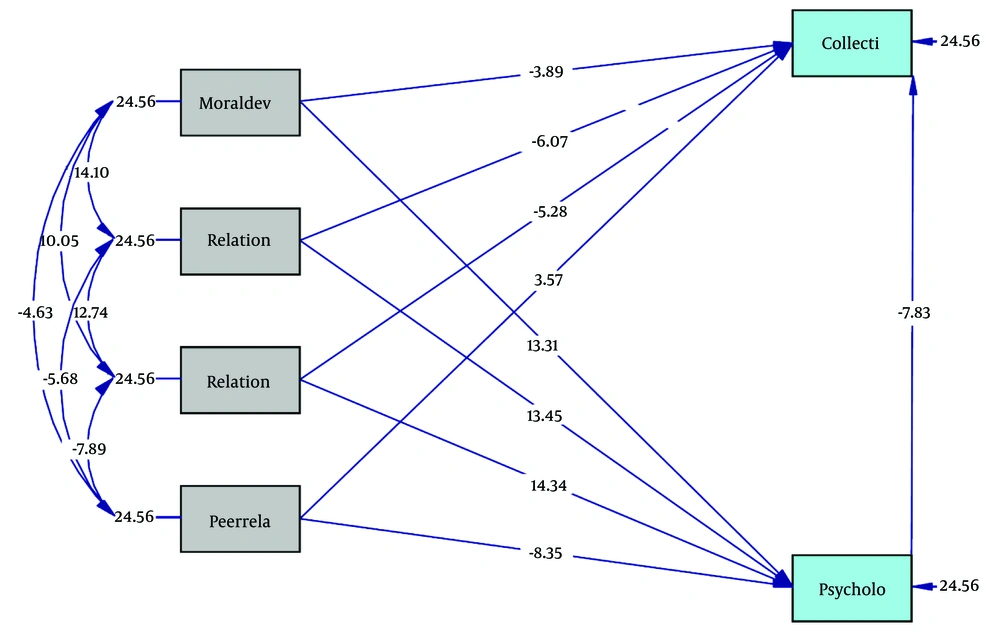

Hypothesis 1: Moral development has a direct, significant negative impact on collective violence, with a standardized coefficient of -0.11, a t-value of -3.89, and a P-value of < 0.001. This indicates that higher levels of moral development significantly decrease the likelihood of engaging in collective violence (Table 4, Figures 2 and 3).

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variable | Standard Coefficient | t-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moral development | Collective violence | -0.11 | -3.89 a | < 0.001 |

| Relationship with father | Collective violence | -0.18 | -6.07 | < 0.001 |

| Relationship with mother | Collective violence | -0.15 | -5.28 | < 0.001 |

| Relationship with peers | Collective violence | 0.09 | 3.57 | < 0.001 |

| Psychological security | Collective violence | -0.27 | -7.83 | < 0.001 |

| Moral development | Psychological security | 0.29 | 13.31 | < 0.001 |

| Relationship with father | Psychological security | 0.30 | 13.45 | < 0.001 |

| Relationship with mother | Psychological security | 0.31 | 14.34 | < 0.001 |

| Relationship with peers | Psychological security | -0.17 | -8.35 | < 0.001 |

Values of Significance and Standard Coefficients in the Conceptual Model of the Research

Hypothesis 2: The relationship with the father has a direct, significant negative impact on collective violence, with a standardized coefficient of -0.18, a t-value of -6.07, and a P-value of < 0.001. This suggests that a stronger relationship with the father significantly reduces the likelihood of engaging in collective violence (Table 4, Figures 2 and 3).

Hypothesis 3: The relationship with the mother has a direct, significant negative effect on collective violence, with a standardized coefficient of -0.15, a t-value of -5.28, and a P-value of < 0.001. A better relationship with the mother directly reduces the chances of engaging in collective violence (Table 4, Figures 2 and 3).

Hypothesis 4: Negative peer relationships have a direct, significant positive effect on collective violence, as indicated by a standardized coefficient of 0.09, a t-value of 3.57, and a P-value of < 0.001. This suggests that negative peer relationships directly increase the likelihood of engaging in collective violence (Table 4, Figures 2 and 3).

Hypothesis 5: Psychological security has a direct, significant negative impact on collective violence, with a standardized coefficient of -0.27, a t-value of -7.83, and a p-value of <0.001. This demonstrates that enhancing psychological security directly reduces the likelihood of engaging in collective violence (Table 4, Figures 2 and 3).

Hypothesis 6: Peer relationships have an indirect negative impact on collective violence through the mediating role of psychological security. The standardized coefficient between peer relationships and psychological security is -0.17 (t-value -8.35, P-value < 0.001), indicating that negative peer relationships significantly reduce psychological security. In turn, psychological security negatively affects collective violence, with a standardized coefficient of -0.27 (t-value -7.83, P-value < 0.001). The indirect effect of peer relationships on collective violence through psychological security is 0.0459, meaning that negative peer relationships indirectly increase the likelihood of collective violence by reducing psychological security (Tables 4 and 5, Figures 2 and 3).

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect (via Psychological Security) | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moral development | Collective violence | -0.11 | (-0.29 × -0.27) = 0.0783 | -0.11 + 0.0783 = -0.0317 |

| Relationship with father | Collective violence | -0.18 | (0.30 × -0.27) = -0.081 | -0.18 + (-0.081) = -0.261 |

| Relationship with mother | Collective violence | -0.15 | (0.31 × -0.27) = -0.0837 | -0.15 + (-0.0837) = -0.2337 |

| Relationship with peers | Collective violence | 0.09 | (-0.17 × -0.27) = 0.0459 | 0.09 + 0.0459 = 0.1359 |

| Psychological security | Collective violence | -0.27 | N/A | -0.27 |

Path Analysis of Direct and Indirect Effects of Independent Variables on Collective Violence

Hypothesis 7: Moral development indirectly impacts collective violence through psychological security. The standardized coefficient between moral development and psychological security is 0.29 (t-value 13.31, P-value < 0.001), indicating that higher levels of moral development significantly enhance psychological security. Psychological security then negatively affects collective violence, with a standardized coefficient of -0.27 (t-value -7.83, P-value < 0.001). The indirect effect of moral development on collective violence via psychological security is 0.0783, suggesting that moral development reduces collective violence by improving psychological security (Tables 4 and 5, Figures 2 and 3).

Hypothesis 8: The relationship with the father has an indirect effect on collective violence through the mediating role of psychological security. The standardized coefficient between the relationship with the father and psychological security is 0.30 (t-value 13.45, P-value < 0.001), showing that a positive paternal relationship significantly improves psychological security. Psychological security, in turn, negatively influences collective violence, with a standardized coefficient of -0.27 (t-value -7.83, P-value < 0.001). The indirect effect of the relationship with the father on collective violence is -0.081, suggesting that a better relationship with the father decreases collective violence through its positive impact on psychological security (Tables 4 and 5, Figures 2 and 3).

Hypothesis 9: The relationship with the mother also indirectly affects collective violence through psychological security. The standardized coefficient between the relationship with the mother and psychological security is 0.31 (t-value 14.34, P-value < 0.001), indicating that a positive maternal relationship significantly enhances psychological security. Psychological security then negatively impacts collective violence, with a standardized coefficient of -0.27 (t-value -7.83, P-value < 0.001). The indirect effect of the relationship with the mother on collective violence is -0.0837, meaning that a supportive relationship with the mother decreases collective violence through improved psychological security (Tables 4 and 5, Figures 2 and 3).

5. Discussion

The results of this study emphasize the significant influence of peer relationships, moral development, and family relationships on collective violence, with psychological security playing a crucial mediating role.

5.1. Direct Relationship Between Moral Development and Collective Violence

The findings revealed that moral development has a direct and significant negative impact on collective violence. This indicates that individuals with higher levels of moral development are less likely to engage in violent collective behaviors. Moral development serves as an essential factor in reducing collective violence, as those with stronger moral values are less inclined to resort to aggression. This outcome is consistent with previous research that highlights the positive effect of moral development in reducing violent tendencies (10, 65-67). Moral development equips individuals with ethical principles that guide them toward peaceful and constructive solutions when facing conflicts. As a result, promoting moral development can be an effective strategy for mitigating collective violence, as those with higher moral standards are more likely to choose non-violent approaches to problem-solving (29).

5.2. Direct Relationship Between Relationship with Father and Collective Violence

The study also demonstrated that the quality of the relationship with the father has a direct and significant negative impact on collective violence. This suggests that a positive and supportive relationship with the father decreases the likelihood of engaging in violent behaviors. The findings indicate that strong paternal relationships can act as protective factors against collective violence. This result aligns with existing literature that underscores the positive role of family relationships in reducing violent behaviors (68-71). The relationship with the father can significantly influence an individual's social and psychological well-being. Positive paternal relationships foster a sense of security and self-confidence, reducing the inclination toward violence. Therefore, enhancing father-child relationships may serve as an effective means of preventing collective violence, as individuals with strong family connections are less prone to violent behaviors (69).

5.3. Direct Relationship Between Relationship with Mother and Collective Violence

The study revealed that the quality of the relationship with the mother has a direct and significant negative impact on collective violence. This indicates that a stronger and more supportive relationship with the mother reduces the likelihood of engaging in collective violence. Supportive maternal relationships can serve as protective factors against violent behaviors. This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating the positive influence of family relationships in reducing violence (68-71). A positive relationship with the mother plays a crucial role in shaping an individual's social and psychological behavior, providing a sense of security and emotional support that steers individuals away from violent tendencies. Therefore, enhancing mother-child relationships may act as an effective strategy for preventing collective violence, as individuals with solid family connections are less prone to engage in violent behaviors (59).

5.4. Direct Relationship Between Relationship with Peers and Collective Violence

The findings also showed that peer relationships have a direct and significant positive impact on collective violence. Specifically, the more negative the quality of peer relationships, the greater the likelihood of collective violence. This suggests that negative peer interactions can act as a risk factor for increasing violent behaviors. These results are consistent with other studies that highlight the detrimental impact of negative peer relationships on violence (3, 72-76). Peer relationships significantly influence social and psychological behaviors, and negative interactions can increase stress and psychological pressure, driving individuals toward violent behaviors. Improving the quality of peer relationships can therefore be an effective strategy for reducing collective violence, as those with healthier peer connections are less likely to resort to violence (36).

5.5. Indirect Relationship Between Moral Development and Collective Violence

The findings suggest that moral development indirectly reduces collective violence through the mediating role of psychological security. Enhancing moral values and ethical education fosters empathy, respect for others, and reduces aggression, thereby discouraging violent behaviors. Psychological security amplifies this effect by providing a sense of safety and stability, further minimizing the likelihood of violent tendencies. This conclusion is consistent with previous research, which demonstrates that strong moral principles and ethical education contribute to non-violent conflict resolution (26-29, 41-44).

5.6. Indirect Relationship Between Relationship with Father and Collective Violence

A positive relationship with the father significantly reduces collective violence through its impact on psychological security. Fathers play a vital role in offering emotional support and guidance, fostering a secure environment that bolsters adolescents' self-confidence and lowers anxiety levels. This sense of security strengthens social bonds and psychological resilience, resulting in a decrease in violent behaviors. These findings align with studies that underscore the importance of paternal involvement in mitigating aggression (27, 30-35, 41-44).

5.7. Indirect Relationship Between Relationship with Mother and Collective Violence

Similarly, a supportive relationship with the mother reduces collective violence through the mediating role of psychological security. Mothers who maintain close, nurturing relationships with their children can alleviate stress and anxiety, thereby decreasing the likelihood of violent behaviors. Strong maternal bonds also provide greater supervision and control over children's actions, reducing opportunities for violence. This conclusion is corroborated by both domestic and international studies that emphasize the role of maternal support in fostering psychological security and curbing violence (27, 30-35, 41-44).

5.8. Indirect Relationship Between Relationship with Peers and Collective Violence

Peer relationships have a complex influence on collective violence. Negative peer relationships undermine psychological security, leading to increased violent behaviors. Experiences such as bullying, social rejection, and unstable peer interactions contribute to heightened anxiety, stress, and feelings of isolation, all of which erode psychological security. Conversely, improving peer relationships enhances psychological security, thereby reducing the likelihood of collective violence. This finding is supported by research that highlights the detrimental effects of negative peer interactions on adolescents' mental health and behavior (27, 33, 36-39, 41-44).

5.9. Direct Relationship Between Psychological Security and Collective Violence

Psychological security plays a crucial mediating role between the independent variables (peer relationships, moral development, and family relationships) and collective violence. Individuals with higher psychological security are less likely to engage in violent behavior, as they are better equipped to manage life's challenges without resorting to aggression. Enhancing psychological security through supportive relationships and moral development proves to be an effective strategy for reducing collective violence. This conclusion aligns with previous studies that have demonstrated the positive influence of psychological security on decreasing violent behaviors (27, 41-44).

5.10. Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this study is the comprehensive conceptual model, which includes independent variables (peer relationships, moral development, and family relationships) and the mediating variable (psychological security). This approach allows for a detailed analysis of both the direct and indirect effects of these variables on collective violence. The use of cluster sampling and a large sample size of 1300 participants enhances the accuracy and validity of the findings.

However, there are several limitations to consider. The use of self-report questionnaires may introduce bias, as participants may provide socially desirable responses, affecting the accuracy of the data. Additionally, the focus on male high school students in Mashhad limits the generalizability of the findings to other demographic groups. The correlational nature of the study also prevents any conclusions about causal relationships.

To address these limitations, future research could incorporate mixed methods such as semi-structured interviews or direct observations to mitigate the influence of socially desirable responses. Expanding the statistical population to include female students and participants from other regions would enhance the generalizability of the results. Additionally, experimental designs could be used to explore causal relationships.

Further research should aim to include more diverse samples, such as female students and those from various geographical regions, to broaden the applicability of the findings. Longitudinal studies would be beneficial in understanding how these relationships evolve over time. Employing mixed methods, including qualitative interviews and direct observations, could provide a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing collective violence. Developing and testing interventions aimed at improving moral development, family relationships, and psychological security would also be valuable. Cross-cultural studies could uncover both universal and culture-specific factors, while additional variables such as socioeconomic status and community environment could further enhance our understanding of collective violence. Lastly, focusing on the policy implications of these findings could help create strategies to reduce violence and promote psychological security in schools.

5.11. Conclusions

This study underscores the crucial role of moral development and psychological security in reducing collective violence. The findings indicate that promoting moral values and ethical education can cultivate empathy, respect, and non-aggressive behavior, thereby curbing violent tendencies. Strong parental relationships, particularly with fathers and mothers, were found to enhance psychological security, which further reduces the likelihood of violent behavior. Moreover, improving peer relationships and addressing negative social interactions can also bolster psychological security and decrease collective violence. The comprehensive conceptual model employed in this study highlights the importance of considering both the direct and indirect effects of social and psychological factors on collective violence, offering a solid foundation for future research and interventions aimed at reducing violence.