1. Background

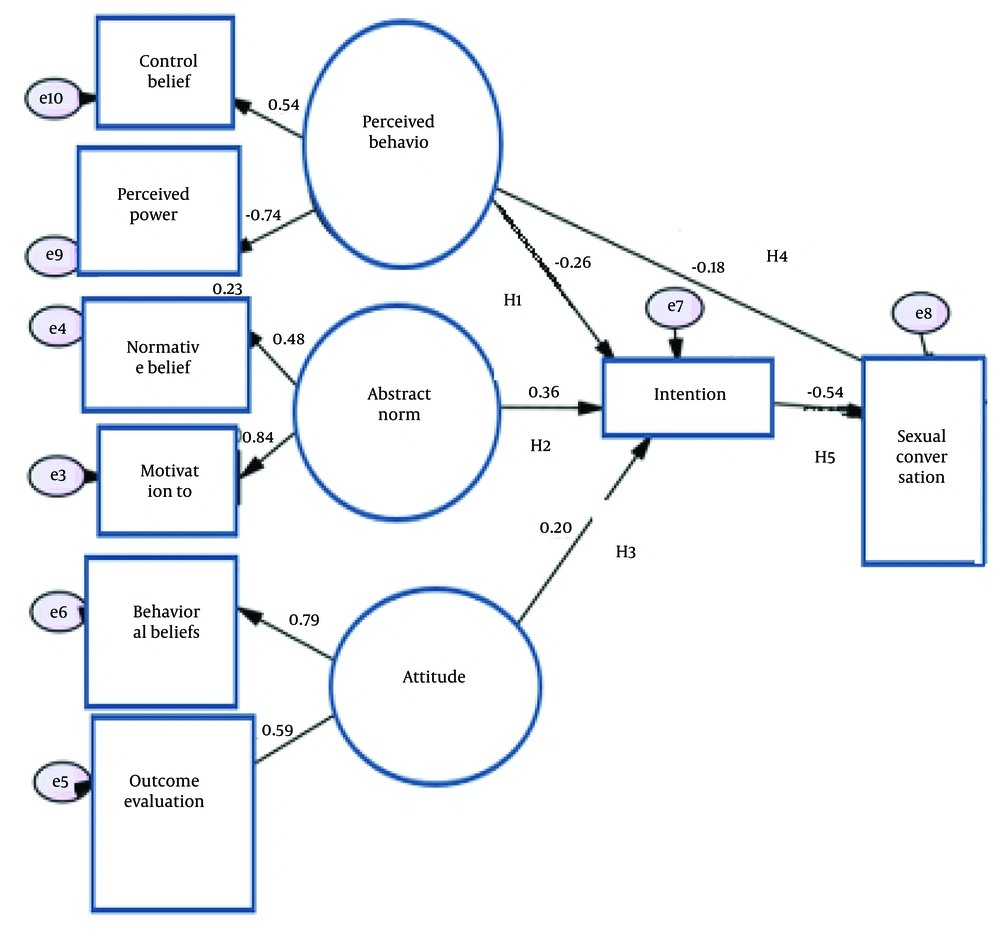

Due to sexuality being a taboo subject in the healthcare system (1), there is a lack of conversation on sexual issues by both patients and medical staff, leading to many problems for patients (1-3). Medical staff refrain from discussing sexual issues for various reasons, such as insufficient knowledge, training, and skills (4), shame (5), time constraints (6), lack of personal ability, unsuitability of their place (6), lack of organizational support, resource constraints, and negative attitudes and beliefs towards sexual issues (4), as well as a lack of referral centers and more specialized services (7, 8). The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is a well-known model that predicts health providers' intentions and behaviors related to sexual issues. Research has shown that the model can predict college students’ intentions (9) and children's intentions (10) to communicate on sexual issues. The TPB was proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen. The main concepts (constructs) of TPB include behavior, intention, attitude toward behavior, and perceived behavioral control (11). More research has applied the TPB model to sexual issues with college students (9), children (10), and patients (12) in the United States and Europe. Only one valid questionnaire with 27 questions based on the TPB model exists for predicting treatment staff conversation with women on sexual issues. The questionnaire, conducted by Salinas et al. (12) in 2011 in the United States, was able to predict health providers’ intentions to talk about sexual issues. Researchers concluded that more research is needed in other countries to confirm the power of this theory in predicting conversations on sexual issues (12). So far, there is no valid questionnaire predicting sexual issues based on the TPB model in Iran, where sexual issues are still a taboo. In this study, the aim is to test the following hypotheses based on the TPB model as outlined in Figure 1:

H1: Perceived behavioral control predicts the intention to converse on sexual issues.

H2: Subjective norm predicts the intention to converse on sexual issues.

H3: Attitude predicts the intention to converse on sexual issues.

H4: Perceived behavioral control predicts conversation.

H5: Behavioral intentions predict conversation.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to develop and psychometrically test a new scale using the TPB, comprising two types of measurement [direct and belief-based (indirect)], to assess treatment staff's intention to converse on sexual issues with postmenopausal women.

3. Methods

In the present study, a mixed-method design (sequential exploratory) was used. This article is based on my doctoral thesis in obstetrics and reproductive health. The study proposal was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Research Council of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (code of ethics: 930568). Inclusion criteria included willingness to participate in the study, being Iranian, and having at least two years of experience in a clinic or private office. This study consists of three phases: A qualitative stage (the first phase) conducted using a directed content analysis approach; an instrument development stage (the second phase), in which a questionnaire is first designed according to the data derived from the qualitative section and the literature review, and then the psychometric properties of the instrument are determined by measuring its validity and reliability. The construct validity was carried out using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Predicting dietary practice behavior among type 2 diabetics using the TPB (the second phase).

In phase 1, a qualitative study was conducted to design the questionnaire items in the present study. The maximum variation purposive and snowball sampling methods were used. The sample size was determined based on theoretical saturation, with 27 participants (13 midwife participants and 14 general practitioners) working in the public and private sectors. Interviews began with a general question such as "Can you tell us about your experience of having a conversation with a menopausal patient on sexual issues?" and continued with semi-structured questions. It should be noted that the interview guide was designed based on the TPB constructs regarding barriers and facilitators, advantages and disadvantages, and other influential factors using the relevant guide by Ajzen and Francis (13).

The interview was recorded using an MP3 player. The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim immediately after the interview, and data saturation was reached when no new data was reported in the interviews. Then, qualitative content analysis based on Graneheim and Lundman (14) was used to analyze the data. The interviews were read several times to gain an overall insight into the data. In the next step, the text was divided into meaning units (words, sentences, or paragraphs). These units were condensed and labeled as codes without compromising their content. Then, codes that were identical in terms of meaning and content were combined and sorted into subcategories and categories.

In phase 2 (Instrument development stage), the questionnaire was developed according to the steps suggested by Ajzen, who developed the TPB model (13). The TPB comprises both direct and indirect (belief-based) measures. Direct measures were used to obtain a general assessment or opinion of the participants. Indirect measures served to examine the participant’s underlying specific beliefs and outcome evaluations (Table 1). Various Likert scales were used in the instrument design. A total of 121 questions were designed based on the findings of the qualitative stage. Abstract norms were measured both directly and indirectly. Four questions were designed for direct abstract norms, 14 questions for normative belief, and 14 questions for the motivation to comply with. Perceived behavioral control was measured directly and indirectly. Perceived indirect behavioral control consists of 4 questions, namely 2 questions for self-efficacy and 2 questions for belief control. Perceived behavioral control consists of two parts: Control belief (23 questions) and perceived power (23 questions). A total of 24 questions were designed to assess the attitude towards conversation on sexual issues. The direct approach consists of 4 questions, and indirect attitude includes behavioral beliefs (10 questions) and outcome evaluation (10 questions). Five clinical scenarios (50 - 80 words) have also been designed based on participants' clinical experience to measure simulated behavioral intent. Six questions were also designed based on the findings of the qualitative stage. Four questions were designed to measure behavior based on the findings of the qualitative stage.

| Constructs | Cronbach Alpha | Test-Retest Reliability | CVI | CVR | Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral control belief | |||||

| Lack of knowledge and clinical skills | 0.83 | 0.96 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Ability to communicate effectively with postmenopausal women | 0.89 | 0.84 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Improper policies concerning health and sex programs | 0.89 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 1 | 0.8 | 6 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 7 | |||

| 1 | 0.8 | 8 | |||

| Low priority to provide sexual services by health provider | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.6 | 9 |

| 0.83 | 0.6 | 10 | |||

| Sexual problems are closely entwined with socio-cultural construct | 0.84 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.8 | 11 |

| 1 | 1 | 12 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 13 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 14 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 15 | |||

| 0.96 | 0.6 | 16 | |||

| 1 | 0.8 | 17 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 18 | |||

| 0.93 | 0.6 | 19 | |||

| 0.83 | 0.6 | 20 | |||

| Opening the discussion of sexual matters | 0.85 | 0.83 | 1 | 1 | 44 |

| 1 | 1 | 45 | |||

| 1 | 0.8 | 46 | |||

| Direct perceived behavioral control | |||||

| No | 0.73 | 0.95 | 1 | 1 | 47 |

| 1 | 1 | 48 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 49 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 50 | |||

| Normative belief | |||||

| Expect to understand religious and cultural sensitivities (from family and community) | 0.72 | 0.95 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 51 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 52 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 53 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 54 | |||

| 0.93 | 0.8 | 55 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 56 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 57 | |||

| Expect scientific and professional performance | 0.79 | 0.91 | 1 | 1 | 58 |

| 1 | 1 | 59 | |||

| Expect to provide services based on respect for privacy and the principle of confidentiality | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 1 | 60 |

| 1 | 1 | 61 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 62 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 63 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 64 | |||

| Motivation to comply with | |||||

| Expect to understand religious and cultural sensitivities (from family and community) | 0.76 | 0.83 | 1 | 1 | 65 |

| 1 | 1 | 66 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 67 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 68 | |||

| 0.96 | 0.8 | 69 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 70 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 71 | |||

| Expect scientific and professional performance | 0.82 | 0.91 | 1 | 1 | 72 |

| 1 | 1 | 73 | |||

| Expect to provide services based on respect for privacy and the principle of confidentiality | 0.81 | 0.9 | 0.96 | 1 | 74 |

| 1 | 1 | 75 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 76 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 77 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 78 | |||

| Direct abstract norms | |||||

| No | 0.71 | 0.9 | |||

| 1 | 0.8 | 79 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 80 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 81 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 82 | |||

| Behavioral beliefs | |||||

| Lead to damage to the dignity and dignity of the health providers and damage to the self-esteem of the menopausal women | 0.82 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 83 |

| 1 | 1 | 84 | |||

| 1 | 0.8 | 85 | |||

| Consolidation of the family foundation | 0.8 | 0.95 | 1 | 1 | 86 |

| 1 | 1 | 87 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 88 | |||

| Promoting mental and sexual health | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 1 | 89 |

| 1 | 1 | 90 | |||

| Improving sexual health literacy | 0.75 | 0.89 | 1 | 1 | 91 |

| 1 | 1 | 92 | |||

| Outcome evaluation | |||||

| Lead to damage to the dignity and dignity of the health providers and damage to the self-esteem of the menopausal women | 0.75 | 0.95 | 1 | 1 | 93 |

| 1 | 1 | 94 | |||

| 1 | 0.8 | 95 | |||

| Consolidation of the family foundation | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1 | 1 | 96 |

| 1 | 1 | 97 | |||

| 0.86 | 1 | 98 | |||

| Promoting mental and sexual health | 0.71 | 0.89 | 1 | 1 | 99 |

| 1 | 1 | 100 | |||

| Improving sexual health literacy | 0.76 | 0.9 | 1 | 1 | 101 |

| 102 | |||||

| Direct attitude | |||||

| No | 0.7 | 0.96 | 1 | 1 | 103 |

| 1 | 1 | 104 | |||

| 0.96 | 1 | 105 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 106 | |||

| Clinical scenario (five questions) | |||||

| No | 0.71 | 0.95 | 1 | 1 | 107 |

| 1 | 1 | 108 | |||

| 1 | 0.8 | 109 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 110 | |||

| 0.96 | 1 | 111 | |||

| Intention of sexual issues | |||||

| Provision of conditions and facilities | 0.76 | 0.84 | 1 | 1 | 112 |

| 1 | 1 | 113 | |||

| Finding the capacity of postmenopausal women for sexual conversation | 0.78 | 0.91 | 1 | 1 | 114 |

| 1 | 1 | 115 | |||

| Empowering the menopausal women for sexual conversation | 0.72 | 0.93 | 1 | 1 | 116 |

| 1 | 1 | 117 | |||

| Behavior | |||||

| Preparing the menopausal women for sex talk | 0.71 | 0.86 | 1 | 1 | 118 |

| 1 | 1 | 119 | |||

| Providing counseling and treatment services | 0.73 | 0.84 | 1 | 1 | 120 |

| 1 | 1 | 121 |

Abbreviation: CVI, Content Validity Index; CVR, Content Validity Ratio.

Content validity was quantitatively evaluated using two measures: The Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and the Content Validity Index (CVI). Ten experts are recommended as optimal for determining content validity (15). Ten expert panel members (including reproductive health specialists, health education specialists, and psychiatrists) evaluated the content validity of the first version of the instrument. The minimum acceptable CVR value (62%) was not obtained for three questions, but all questions had an acceptable CVI, i.e., above 0.70. To determine reliability, internal consistency and stability were measured. Cronbach's alpha calculation and test-retest were used to investigate internal consistency and stability, respectively. A separate sample was used for the reliability testing phase. To calculate Cronbach's alpha coefficient, the questionnaire was distributed among the study population (n = 40). Stability was evaluated using the test-retest method (n = 40). The treatment staff completed the instrument in two steps with a two-week interval. Then, the correlation between the two stages was determined. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha values were all above 0.70.

In phase 3 (predictability of the TPB-based model), the researcher first introduced herself and explained the study objectives. The research participants were also assured about the confidentiality of their information. Participants then signed the written informed consent form. Inclusion criteria included willingness to participate in the study, being Iranian, and having at least two years of experience in a clinic or private office. Exclusion criteria included unwillingness to continue cooperation at any stage of the research.

The data were collected using the TPB because it is recognized as a well-established theoretical framework. Additionally, the relationships between the constructs of planned behavior theory are well-documented, making CFA more appropriate than exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was conducted in two steps. In the first step, the assessment of the measurement model was performed with CFA to evaluate the convergent and discriminant validity of the tool. The sample size was estimated according to the rule of thumb, with 100 samples deemed sufficient as recommended by Hair et al. (16). A total of 116 samples, comprising 60 midwives and 56 general practitioners, were randomly selected. Secondly, SEM analysis was used to verify relationships and associations among variables. The sample size was again estimated according to the rule of thumb. In the most common method of parameter estimation in SEM, i.e., maximum likelihood, at least 100 to 200 subjects are required, and some experts believe that 30 participants are needed for each construct. A separate sample was recruited to examine SEM, with a total of 208 samples comprising 103 midwives and 105 general practitioners randomly selected.

Goodness-of-fit indices were used to test for model fit. The indices used to assess model fit included the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Data analysis was performed using the Pearson correlation coefficient, regression coefficient, and path analysis in AMOS version 21 and SPSS version 22. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

From the data analysis, 226 codes, 54 sub-categories, and 18 categories were obtained, which were classified under the themes of attitude, perceived behavioral control, abstract norms, intention, and behavior (Table 1).

A total of 78.4% of participants were female, and 21.6% were male. The mean ± SD of participants’ age was 39.94 ± 8.33 years (Table 2).

| Variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 163 (78.4) |

| Man | 45 (21.6) |

| Job | |

| Midwife | 103 (49.5) |

| Female general practitioners | 60 (28.8) |

| Male general practitioners | 45 (21.6) |

| History of participating in conferences and educational seminars | |

| Yes | 104 (50) |

| No | 104 (50) |

| History of participating in sexual workshops | |

| Yes | 31 (14.9) |

| No | 177 (85.1) |

| History of participating in communication skills workshop | |

| Yes | 46 (22.1) |

| No | 162 (77.83) |

These correlations ranged from -0.002 to 0.572. The highest correlation was observed between behavior and behavioral intention (r = 0.572, P < 0.001), and the lowest correlation was observed between perceived power and behavioral intention (r = -0.002, P = 0.982) (Table 3). Before investigating the significant relationships between the measurement model and the model coefficients, it is necessary to evaluate the model adequacy using the fit indices. The GFI, CFI, AGFI, and RMSEA indices were equal to 0.92, 0.9, 0.89, and 0.079, respectively. Also, the degree of freedom was equal to 2.87 in chi-square, which is less than 5. Therefore, it can be concluded that the model has a good fit (the data were not shown in the table).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Mean Scores for Variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 39.94 ± 8.33 |

| Behavior | R = 0.111; P = 0.109 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3.3 ± 0.89 |

| Normative belief | R = 0.042; P = 0.605 | R = 0.078; P = 0.34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16.64 ± 12.67 |

| Motivation to comply with | R = 0.016; P = 0.831 | R = 0.071; P = 0.357 | R = 0.519; P < 0.001 | - | - | - | - | - | 73.94 ± 10.91 |

| Perceived power | R = -0.122; P = 0.08 | R = -0.157; P = 0.023 | R = -0.026; P = 0.744 | R = 0.106; P = 0.167 | - | - | - | - | 10.77 ± 19.17 |

| Control Belief | R = 0.05; P = 0.938 | R = -0.086; P = 0.215 | R = 0.026; P = 0.753 | R = 0.228; P = 0.003 | =0.308; P = 0.001 | - | - | - | 162.28 ± 10.96 |

| Behavioral beliefs | R = 0.045; P = 0.515 | R = 0.1960; P = 0.005 | R = 0.139; P = 0.090 | R = 0.151; P = 0.048 | R = -0.026; P = 0.706 | R = 0.211; P = 0.002 | - | - | 43.53 ± 7 |

| Outcome evaluation | R = 0.081; P = 0.244 | R = 0.086; P = 0.218 | R = 0.292; P = 0.001 | R = 0.232; P = 0.002 | R = -0.042; P = 0.548 | R = 0.258; P < 0.001 | R = 0.436; P = 0.001 | - | 13.56 ± 5.29 |

| Behavioral intention | R = 0.123; P = 0.077 | R = 0.572; P = 0.001 | R = 0.302; P = 0.001 | R = 0.33; P = 0.352 | R = -0.065; P = 0.352 | R = -0.002; P = 0.98 | R = 0.292; P = 0.001 | R = 0.294; P = 0.001 | 28.76 ± 6.55 |

The CFA was performed, and all factor loadings were significant at P < 0.05 on their underlying construct (Table 4).

| Variables | Factor Loadings | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.049 | |

| Behavioral beliefs | 0.79 | |

| Outcome evaluation | 0.59 | |

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.007 | |

| Behavioral control belief | 0.54 | |

| Perceived power | 0.74 | |

| Abstract norm | 0.006 | |

| Normative belief | 0.48 | |

| Motivation to comply with | 0.84 |

It can be stated that there was a positive and significant relationship between attitude (B = 0.2; P = 0.05) and abstract norm (B = 0.36; P < 0.001) with intention. There was a negative and significant relationship between behavioral control and intention (B = -0.18; P = 0.04). It can be stated that behavioral intention had a positive and significant effect on behavior, but perceived behavioral control had a significant negative effect on this variable (Figure 1, Table 5).

| Path Analysis | Standardized Coefficient (β) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Direct path | ||

| Attitude → intention | 0.2 | 0.05 |

| Abstract norm →intention | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Perceived behavioral control → intention | -0.26 | 0.006 |

| Intention → sexual conversation (behavior) | 0.54 | < 0.001 |

| Perceived behavioral control → sexual conversation (behavior) | -0.18 | 0.04 |

| Indirect path | ||

| Attitude → intention → sexual conversation (behavior) | 0.107 | 0.04 |

| Abstract norm abstract norm → intention → sexual conversation (behavior) | 0.19 | 0.05 |

| Perceived behavioral control → intention → sexual conversation (behavior) | -0.14 | 0.04 |

The value of the squared multiple correlation (R2) for explaining variance in intention is 24%. This means that attitude, abstract norms, and perceived behavioral control were able to predict 24% of the intention. R2 for explaining variance in behavior was 37%, indicating that intention and perceived behavioral control were able to predict 37% of the behavior (Figure 1 and Table 6). The effect of sex (male and female) and type of profession (gynecologists and obstetricians) was studied as a group, and results showed no significant difference between the groups (the data were not shown in the table).

| Dependent (Endogenous) Variables | Squared Multiple Correlation |

|---|---|

| Intention | 24% |

| Behavior | 37% |

Frequency and percentage of responses of the treatment staff to the behavior question: When the patients were asked, “How often do you talk to your menopausal clients about sexual issues?” the responses were as follows: Never (8.1%), rarely (16.3%), sometimes (36.1%), often (30.8%), and almost always (8.7%). These data indicate the frequency with which treatment staff engage in conversations about sexual issues with their menopausal clients (the data were not shown in the table).

5. Discussion

The present study showed a positive and significant relationship between abstract norms and attitude with intention and behavior in the model testing section. In other words, treatment staff held a generally positive view toward conversations on sexual issues with postmenopausal women, considering these conversations beneficial for them. Additionally, social pressures exerted by important others had the most impact among influencing variables, leading to the provision of sexual counseling by treatment staff to postmenopausal women. There was a negative and significant relationship between perceived behavioral control and intention, suggesting that the medical staff surveyed in the present study experience barriers to discussing sexual issues with postmenopausal women.

Findings from the structural equation model used in the present study showed that approximately 50% of the participants intended to have conversations about sexual issues with postmenopausal women. The two variables of perceived intention and behavioral control can predict 37% of changes in conversations on sexual issues among midwives and general practitioners. The findings of this study support the hypothesized relationship between attitude and intention in the TPB conceptual framework. The attitude component of the TPB included perceived belief and perceived outcome of discussing sexual issues with menopausal women. Consistent with our findings, a study indicated that perceived outcomes were significant predictors of the intention of parent-child sexual communication (PCSC) (17).

Furthermore, the findings of this study support that the perceived behavioral control component of the TPB was significantly associated with intentions to discuss sexual topics. Consistent with our study, Salinas et al. (12) found a negative and significant relationship between perceived behavioral control and the intention to have conversations about sexual issues. However, the effect of perceived behavioral control on the intention to have sexual conversations was twofold (26%) in the current study compared to the study by Salinas et al. (11%) (12). It seems that the medical staff surveyed in the present study experience more barriers than the relevant gynecologists in the United States.

Our study showed that perceived behavioral control has direct and indirect effects on behavior, with most of its effect being indirect through intention to discuss sexual issues. This finding is consistent with Salinas et al.’s study (12), which found that the two variables of intention and perceived behavioral control were able to predict 29% of the changes in the sexual conversation intention of obstetricians and 26% of healthcare providers, consistent with the current study (24%).

Of the three components of the TPB, subjective norms are the strongest and most important predictor of the intention to talk about sexual issues, which is consistent with previous studies (12). In the USA, a study (12) found a positive and significant relationship between subjective norms and the intention of healthcare providers and gynecologists. Another study in the USA (2015) found that subjective norms were the only significant predictor of PCSC intention (18). Interestingly, subjective norms had the weakest and least significant associations with the intentions of parents to talk with children about different sexual topics in a third study conducted in the USA (17).

Additionally, the findings of this study support that the TPB model aligns with other models like the Health Belief Model (19), PLISSIT Model (20), and the Integrative Model of Behavioral (20), which could predict sexual communication. The reliability of the questionnaire used in the present study was calculated using Cronbach's alpha, which was higher than 0.70, consistent with Salinas et al.'s study developing a questionnaire to measure intentions toward initiating a dialogue about sexual health with women (12).

Consistent with our study, findings from previous studies supported the TPB as a model for predicting an individual’s intention to report sexual harassment (21), parents’ intention for communication with their child about sexual topics (17), healthcare providers’ intention to consult on sexual matters (22), and physicians’ intention toward initiating a dialogue about sexual health with women (12).

In the present study, of the 208 participants, 8.1% never, 16.3% rarely, 36.1% sometimes, 30.8% often, and 8.7% almost always had conversations with their patients about sexual issues. A systematic review of twenty-nine studies from 10 countries (29% in the USA) concluded that only 21% of providers assess patients’ sexual concerns (23). In Azar et al., most nurses and midwives reported that they do not feel comfortable discussing patients' sexual concerns, viewing sexuality as a 'too private issue to discuss' (24). Comparing our results with other studies showed that the participants were more concerned with sexual issues.

One of the strengths of the present study is that it does not have the limitations of previous studies. In Salinas et al.'s study, which used the questionnaire on predicting conversations on sexual issues, only one question was used to measure sexual conversation behavior, which investigated the frequency of sexual conversations by the treatment staff in the past month. The relatively low sample size is one of the main limitations of the present study (12). Sexual conversation behavior has also been investigated in a self-reported manner. There is a need for more objective data, and therefore, attempts should be made to ask clients whether they want the treatment staff to ask sexual questions from them in the waiting room in future studies.

The statistical power of SEM is limited by the complexity of the theoretical model and its sensitivity to the sample size. Additionally, SEM is limited by the fact that it can only assess linear relationships. Future research should include the application of constructs of TPB, including attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, into education programs, especially in the field of sexual counseling.

5.1. Conclusions

Attitudes and abstract norms have positive and significant effects, while perceived behavioral control has significant negative effects on sexual conversation intention and behavior. The value of the multiple predicted coefficient (R2) was 0.20 for sexual conversation intention and 0.37 for sexual conversation. Considering the acceptability of the TPB model for sexual conversation, it is suggested that this model be used in future educational intervention research.