1. Background

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a prevalent chronic musculoskeletal disorder, particularly affecting older adults. As the global population ages, the incidence of KOA continues to rise, posing a significant public health challenge due to its profound impact on mobility and quality of life. The KOA is characterized by joint pain, stiffness, and progressive degeneration of articular cartilage, leading to functional decline and difficulty performing essential daily activities (1, 2). Among these challenges, difficulty in executing the sit-to-stand (STS) movement is particularly problematic, as it is a fundamental prerequisite for mobility and independence. The STS task, which involves transitioning from a seated to a standing position, is critical for functional autonomy as it precedes essential activities like walking and general locomotion (3-5). Successful execution of the STS task relies on coordinated lower limb strength, balance, and postural control, which are often impaired in individuals with KOA (4-10).

Two key biomechanical parameters influencing STS performance are vertical ground reaction force (vGRF) and center of pressure (COP). The vGRF, based on Newton’s third law, represents the reactive force exerted by the ground on the body during movement. It serves as a crucial indicator of force generation capacity during weight-bearing activities, including STS performance. In KOA patients, reduced vGRF has been associated with diminished force production in the lower limbs, leading to inefficient movement patterns and increased reliance on compensatory strategies. The COP, on the other hand, represents the point of application of the resultant ground reaction force and is a key measure of postural stability and balance control. Changes in COP trajectory can signal postural instability and altered movement strategies in KOA patients attempting to complete the STS task (4-10). Dysfunction in these biomechanical parameters is associated with increased fall risk, impaired mobility, and decreased functional independence. Therefore, understanding biomechanical adaptations in KOA is essential for designing targeted interventions aimed at improving movement efficiency and overall functional performance (4-10).

To alleviate the symptoms of KOA, various physiotherapy interventions have been explored, including exercise therapy, manual therapy, and soft tissue techniques (11-14). Among these, instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization (IASTM) has gained attention as a treatment option due to its potential to improve soft tissue mobility and reduce pain (15, 16). The IASTM employs specialized tools to mobilize soft tissues, aiming to promote healing, decrease adhesions, and improve tissue function. Its effectiveness may stem from mechanisms such as improved blood circulation, reduced tissue viscosity, adhesion disruption, and promoting proper alignment of tissue fibers (15-17). Previous research has demonstrated that IASTM can effectively reduce pain, enhance range of motion, and improve functional performance in individuals with knee-related musculoskeletal conditions (18-22). However, its impact on functional biomechanics in KOA, particularly in relation to parameters like vGRF and COP, remains insufficiently studied.

2. Objectives

Although previous studies have highlighted the general benefits of IASTM for musculoskeletal conditions and its clinical efficacy in reducing pain and improving range of motion, its specific effects on STS performance and biomechanical parameters in KOA patients remain underexplored. Investigating biomechanical outcomes is crucial, as they provide objective, quantitative insights into movement quality, which cannot be fully captured by patient-reported outcomes or clinical symptoms alone. A deeper understanding of these biomechanical changes can guide evidence-based rehabilitation approaches, ultimately enhancing functional independence and movement efficiency in KOA patients.

To our knowledge, no studies have examined the influence of IASTM on kinetic variables, such as vGRF and COP, during the STS task in this population. The primary objective of this study was to assess the effects of IASTM on kinetic variables, including vGRF and COP, during the STS task in individuals with KOA. Additionally, the study evaluated whether IASTM enhances lower limb strength. The intervention consisted of four sessions, as previous research has suggested that acute and short-duration treatments can influence clinical outcomes, making it important to assess the short-term effects of IASTM (23-26). By comparing IASTM to a sham intervention, this research aimed to determine whether IASTM provided meaningful improvements in strength and biomechanical function, ultimately contributing to greater independence in individuals with KOA.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study utilized a parallel, randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical trial design to evaluate the effects of IASTM on lower limb strength and biomechanical performance during the STS task in patients with moderate KOA. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups: An IASTM intervention group with exercise or a sham treatment group with exercise. Measurements were conducted at two time points: before and 48 hours after completing the intervention.

3.2. Participants

Thirty-three participants with unilateral KOA volunteered for this study. The sample size was determined using pilot data, with calculations performed in G*Power software (27), assuming an alpha level of 0.05, a power of 80%, and a medium effect size based on the pilot data, resulting in a required sample size of 28. To account for 15% potential dropouts, 33 participants were recruited, and 30 completed the study, as three participants withdrew for personal reasons.

Inclusion criteria included adults aged 40 years or older with a diagnosis of moderate unilateral KOA (Kellgren-Lawrence grades 2 or 3), the ability to walk independently without assistive devices, a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain score between 3 and 7, a positive Clarke’s test, and a Body Mass Index (BMI) between 18.5 and 29.9.

Exclusion criteria included any significant orthopedic, neurological, or rheumatologic conditions affecting the lower limbs or lower back, active low back pain, intra-articular injections within the last six months, severe knee deformities, candidacy for total knee replacement, a leg length discrepancy exceeding 1.5 cm, regular use of NSAIDs or other pain medications in the two weeks preceding the study, or participation in an exercise program within the past three months (28, 29).

Participants were randomly allocated to the intervention or sham group using block randomization (1:1 allocation ratio). Randomization was conducted by an independent researcher using sealed, opaque envelopes to ensure allocation concealment. Treatments for the two groups were administered on separate days to minimize the chance of participants observing or discussing interventions with each other. This double-blind design ensured that both participants and outcome assessors were blinded to group assignments. All participants provided written informed consent before participation. The study was approved by the Tarbiat Modares University Ethics Committee and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (registration number: IRCT20201128049511N2).

3.3. Procedure

Participants attended two evaluation sessions at the Research and Treatment Center for Movement Disorders at Tarbiat Modares University: one conducted before and another 48 hours after completing the fourth session of IASTM treatment. The selection of four sessions was based on existing literature demonstrating the immediate and short-term effects of IASTM (23-26). During each session, lower limb strength was assessed using a hand-held dynamometer (Lafayette Instrument Co., Lafayette, IN, USA), and biomechanical performance during the STS task was evaluated using a force platform (9286BA; Kistler Co., Winterthur, Switzerland) to collect vGRF and COP data. Force data were recorded at a 1000 Hz sampling frequency.

Additionally, to accurately detect the onset of the STS task, kinematic data were required. Reflective markers were attached to the pelvis at anatomical landmarks consistent with the Vicon Plug-in-Gait lower body model to capture relevant motion. Strength measurements for knee flexors, knee extensors, plantar flexors, and dorsiflexors were conducted using a hand-held dynamometer. Each muscle group was assessed in a specific position, with three trials lasting five seconds each, and a 30-second rest interval between trials. Strength measurements were conducted after a full explanation of the procedure and a familiarization process.

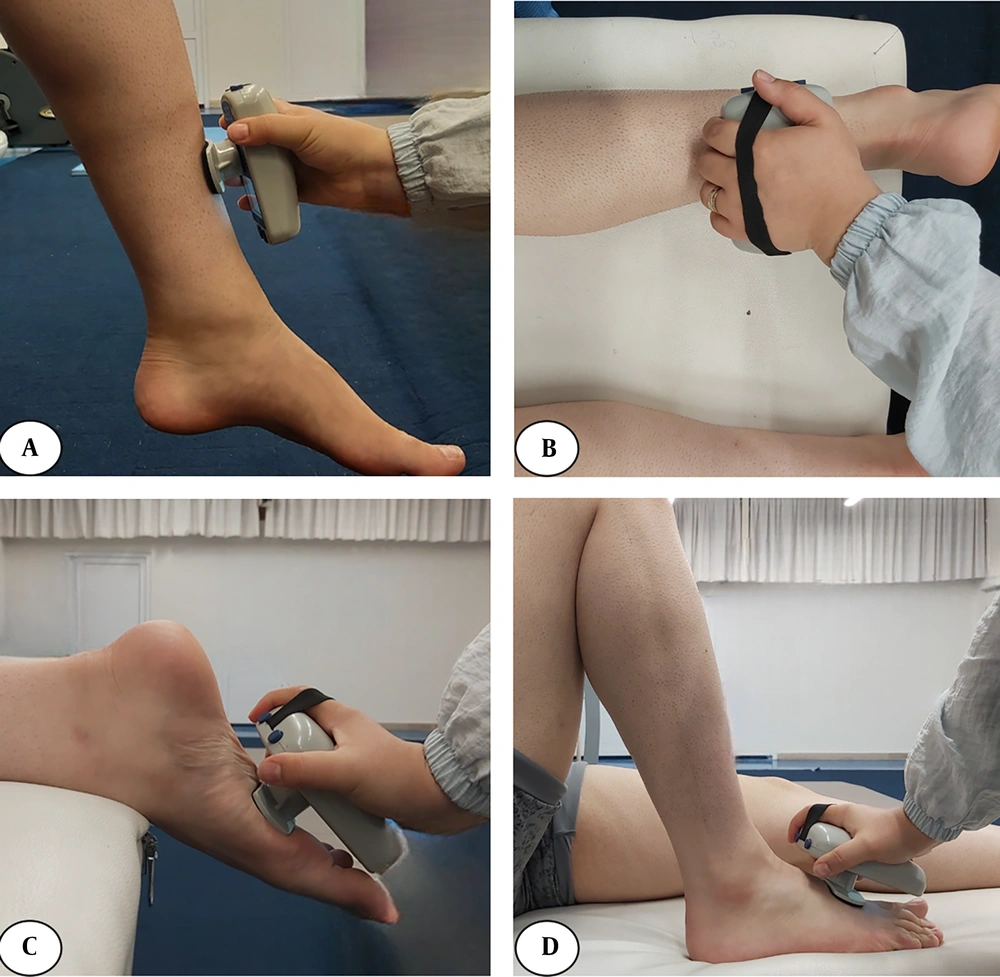

For knee extensors, participants were seated, extending the knee from 90° flexion, with the dynamometer positioned above the ankle (30, 31). For knee flexors, participants were positioned prone with the dynamometer placed above the ankle (32). For plantar flexors, participants were in a prone position with the dynamometer placed on the sole of the foot. For dorsiflexors, participants were supine with the dynamometer placed on the dorsum of the foot (30, 33) (Figure 1).

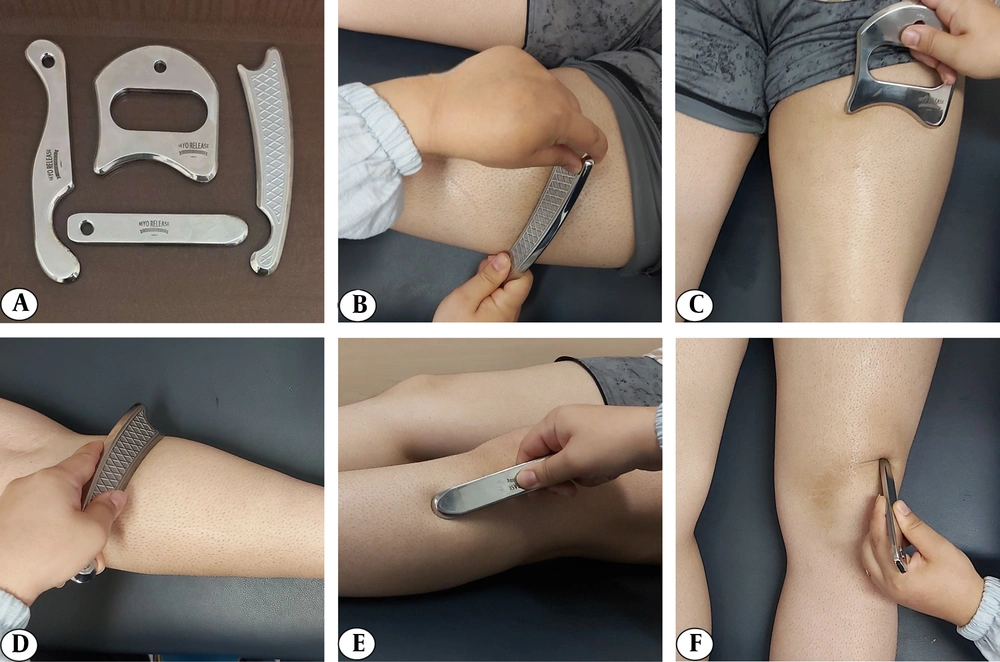

For the STS assessment, participants sat on a chair with their hips and knees flexed at 90°. They were instructed to stand up from the chair with their arms crossed over their chest, ensuring both feet were placed on the force platform. The IASTM group received treatment from a certified physiotherapist using specialized tools following the HawkGrip method to mobilize soft tissue around the knee and lower limb. The targeted areas included the quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius, tibialis anterior muscles, and soft tissue surrounding the patella. Initially, tissue irregularities were assessed using two techniques: Sweeping (longitudinal strokes) and fanning (arcing movements with a fixed point). Based on this assessment, treatment strokes were applied to areas exhibiting redness, producing a vibratory sensation, or corresponding to patient-reported pain. The treatment included sweeping, fanning, and brushing (small, localized strokes). Additionally, framing — a technique involving strokes around the patella — was used to break adhesions and improve mobility (34, 35). Each session lasted 15 minutes and was performed using a standardized set of tools (HGpro Multi-Tool, USA; and IS-3, IS-4, IS-22, Iran) (Figure 2).

The sham group underwent a similar procedure but with minimal pressure applied and no therapeutic intent. None of the participants in either group had prior experience with IASTM. To maintain blinding, the sham group received treatment over the same anatomical regions as the IASTM group but with a light-touch application of the instrument, ensuring they remained unaware of their allocation. To further reinforce blinding, treatment sessions for each group were scheduled separately to prevent cross-group interactions. Importantly, none of the participants in the sham group reported suspicion regarding their group assignment, preserving the integrity of the study's blinding procedures. To uphold ethical standards, participants in the sham group were offered free routine physiotherapy interventions following the study.

In addition to the IASTM intervention, both groups participated in a supervised exercise program consisting of strengthening and stretching exercises for the knee extensors, flexors, plantar flexors, and dorsiflexors. These exercises were designed to complement the IASTM treatment and were delivered under the supervision of a physiotherapist (36-38).

3.4. Data Extraction

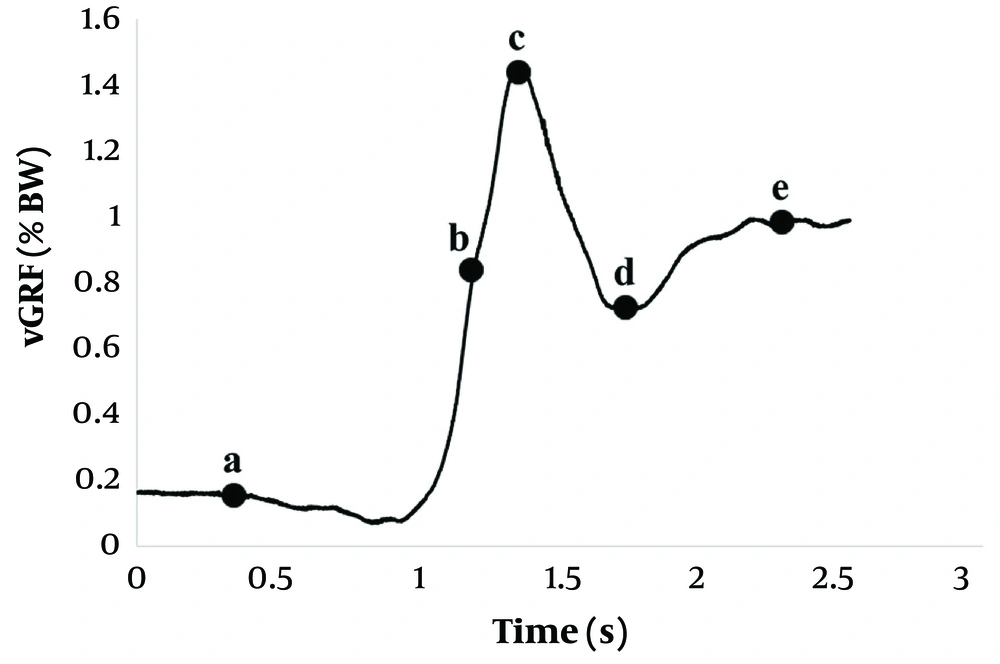

For strength assessments, peak values from the hand-held dynamometry were extracted and normalized to body weight. Biomechanical variables during the STS task, including force, velocity, time, and impulse, were derived from the vGRF data using established protocols (7, 9, 10). The vGRF analysis commenced with identifying the start of the movement, marked by a decrease in vGRF below the baseline sitting value (Figure 3A). The moment of hip lift-off was determined using motion markers attached to the pelvis, signifying the transition from seated to standing (Figure 3B). The peak value was identified at Figure 3C, and the minimum value following the peak was at Figure 3D. The end of the STS task was marked when the ground reaction force values stabilized and returned to the participant's body weight, reflecting the completion of the standing phase and the achievement of postural stability (Figure 3E).

From the vGRF curve, key metrics were extracted, including the force between the start of the movement and hip lift-off, calculated as the difference in values at these two points (Force1), and the force between hip lift-off and the peak value (Force2). Additionally, time and impulse were calculated for three distinct intervals: From the start of the movement to hip lift-off (Time1 and Impulse1), from hip lift-off to the peak vGRF (Time2 and Impulse2), and from the peak vGRF to the minimum value of vGRF after reaching the peak (Time3 and Impulse3). Time measurements were used to evaluate movement speed, while impulse was determined as the cumulative force exerted over time.

The rate of force development, referred to as velocity in previous similar literature (7, 9, 10), was calculated for two specific periods: the phase between hip lift-off and peak vGRF (Velocity1), and the phase from peak to minimum force (Velocity2). These parameters provided detailed insights into the dynamic aspects of the STS movement.

Furthermore, the Kistler measurement, analysis, and reporting software (Kistler-MARS software) was employed to evaluate additional parameters, such as weight transfer time and COP sway velocity. Weight transfer time was defined as the duration required for the center of mass to transition from a seated position to full weight bearing on the feet, offering insights into the efficiency of weight-shifting mechanisms. The COP sway velocity, measured as the average velocity of the COP movement over the base of support during the rising phase, provided a quantitative assessment of postural control and stability. These comprehensive analyses aimed to capture the multifaceted biomechanical characteristics of the STS task and their responsiveness to intervention.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed the normality of the data. Baseline differences between groups were assessed using independent t-tests. A mixed ANOVA was employed to evaluate group (IASTM vs. sham) and time (pre- vs. post-intervention) effects. Levene's test for equality of variances and Box's test of equality of covariance matrices confirmed that assumptions of homogeneity of variance and covariance were met. The alpha level was set at 0.05, and partial eta squared values of 0.01, 0.06, and 0.138 were used to indicate small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively.

4. Results

All 30 participants completed the treatment sessions and were included in the analysis. In the IASTM group, there were 13 females and 2 males, with a mean age of 57.73 ± 8.54 years (95% CI: 53.00 - 62.46) and a mean BMI of 27.46 ± 2.95 kg/2 (95% CI: 25.82 - 29.10). In the sham group, there were 12 females and 3 males, with a mean age of 58.27 ± 7.36 years (95% CI: 54.19 - 62.34) and a mean BMI of 27.59 ± 2.82 kg/m2 (95% CI: 26.02 - 29.15). Statistical analysis confirmed no significant differences between the groups in age (P = 0.277) or BMI (P = 0.856), confirming the baseline similarity of the two groups. Descriptive data for peak strength variables and STS biomechanics are presented in Table 1. Independent t-tests showed no significant between-group differences at baseline for any measured variables (P > 0.05).

| Variables | IASTM Group | Sham Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | |

| Strength values | ||||

| Knee extensors | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.07 - 0.08) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (0.10 - 0.12) | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.07 - 0.09) | 0.08 ± 0.02 (0.07 - 0.10) |

| Knee flexors | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.08 - 0.09) | 0.11 ± 0.02 (0.10 - 0.12) | 0.08 ± 0.02 (0.07 - 0.09) | 0.09 ± 0.02 (0.08 - 0.11) |

| Plantar flexors | 0.09 ± 0.01 (0.08 - 0.10) | 0.12 ± 0.01 (0.11 - 0.13) | 0.09 ± 0.02 (0.08 - 0.11) | 0.10 ± 0.02 (0.09 - 0.12) |

| Dorsi flexors | 0.10 ± 0.02 (0.09 - 0.11) | 0.11 ± 0.03 (0.09 - 0.13) | 0.10 ± 0.02 (0.09 - 0.11) | 0.10 ± 0.01 (0.09 - 0.11) |

| STS biomechanics | ||||

| Force1 (N/BW) | 0.39 ± 0.31 (0.20 - 0.57) | 0.28 ± 0.21 (0.15 - 0.40) | 0.21 ± 0.25 (0.06 - 0.36) | 0.21 ± 0.23 (0.07 - 0.36) |

| Force2 (N/BW) | 0.65 ± 0.31 (0.47 - 0.83) | 0.74 ± 0.23 (0.60 - 0.88) | 0.78 ± 0.25 (0.63 - 0.94) | 0.79 ± 0.24 (0.64 - 0.93) |

| Time1 (s) | 0.61 ± 0.19 (0.50 - 0.72) | 0.67 ± 0.32 (0.48 - 0.85) | 0.60 ± 0.20 (0.48 - 0.72) | 0.60 ± 0.10 (0.54 - 0.66) |

| Time2 (s) | 0.29 ± 0.22 (0.16 - 0.42) | 0.24 ± 0.12 (0.17 - 0.32) | 0.29 ± 0.16 (0.19 - 0.39) | 0.23 ± 0.07 (0.19 - 0.28) |

| Time3 (s) | 1.25 ± 0.24 (1.11 - 1.39) | 1.23 ± 0.22 (1.10 - 1.36) | 1.27 ± 0.40 (1.03 - 1.51) | 1.24 ± 0.23 (1.10 - 1.38) |

| Impulse1 (N.s/BW) | 0.11 ± 0.08 (0.06 - 0.15) | 0.07 ± 0.05 (0.04 - 0.10) | 0.06 ± 0.06 (0.02 - 0.10) | 0.06 ± 0.05 (0.03 - 0.09) |

| Impulse2 (N.s/BW) | 0.24 ± 0.12 (0.17 - 031) | 0.19 ± 0.06 (0.16 - 0.23) | 0.19 ± 0.05 (0.15 - 0.22) | 0.19 ± 0.03 (0.16 - 0.21) |

| Impulse3 (N.s/BW) | 1.23 ± 0.25 (1.09 - 1.38) | 1.16 ± 0.22 (1.03 - 1.30) | 1.20 ± 0.36 (0.98 - 1.41) | 1.17 ± 0.20 (1.05 - 1.29) |

| Velocity1 (N/s.BW) | 2.87 ± 1.54 (1.98 - 3.76) | 3.47 ± 1.57 (2.56 - 4.38) | 3.08 ± 1.67 (2.07 - 4.10) | 3.49 ± 1.06 (2.84 - 4.13) |

| Velocity2 (N/s.BW) | 0.67 ± 0.30 (0.50 - 0.85) | 0.68 ± 0.33 (0.49 - 0.87) | 0.55 ± 0.32 (0.35 - 0.74) | 0.63 ± 0.26 (0.47 - 0.79) |

| Weight transfer (s) | 1.80 ± 0.46 (1.53 - 2.07) | 1.76 ± 0.48 (1.48 - 2.04) | 1.75 ± 0.42 (1.49 - 2.01) | 1.91 ± 0.64 (1.52 - 2.30) |

| COP velocity (mm/s) | 161.12 ± 71.96 (119.57 - 202.67) | 156.70 ± 70.02 (116.27 - 197.14) | 151.93 ± 40.80 (127.28 - 176.59) | 121.22 ± 37.36 (98.64 - 143.80) |

Abbreviations: STS, sit-to-stand; IASTM, instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization; COP, center of pressure.

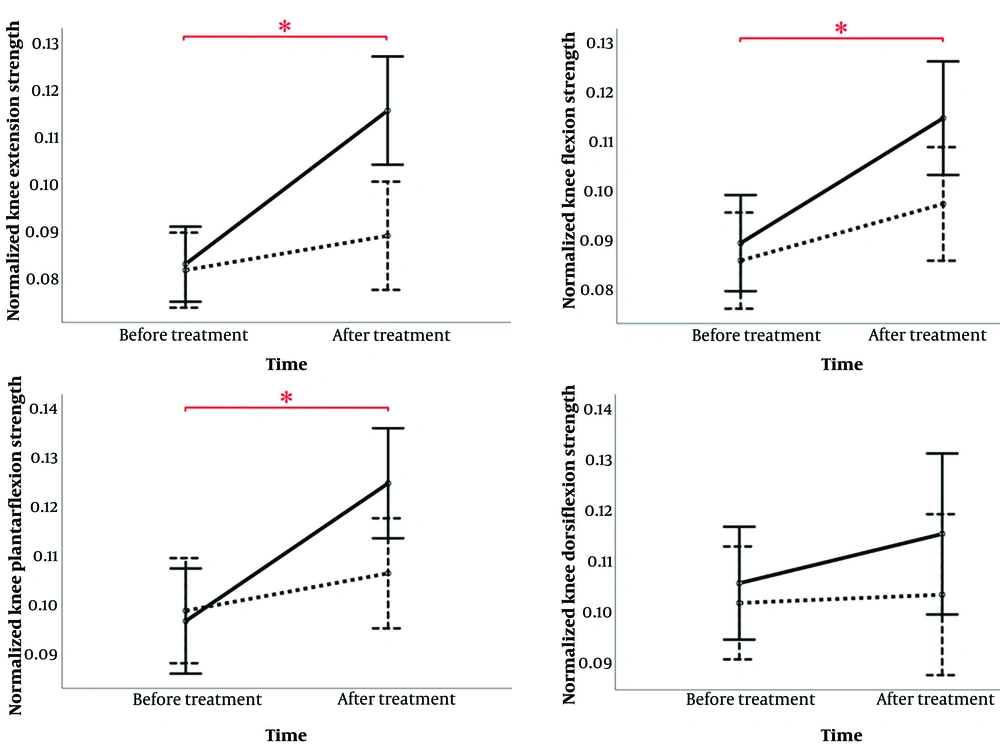

The mixed ANOVA analysis revealed significant findings for strength outcomes. For peak knee extensor strength, there were significant effects for time (P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.553), group (P = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.165), and the time × group interaction (P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.332). For knee flexor strength, significant effects were observed for time (P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.455) and the time × group interaction (P = 0.046, ηp2 = 0.105), while the group effect was not significant (P = 0.108, ηp2 = 0.090). Similarly, for plantar flexors, significant effects were found for time (P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.448) and the time × group interaction (P = 0.011, ηp2 = 0.211), with no significant group effect (P = 0.227, ηp2 = 0.052). In contrast, dorsiflexors showed no significant effects for time (P = 0.254, ηp2 = 0.046), group (P = 0.336, ηp2 = 0.033), or the time × group interaction (P = 0.414, ηp2 = 0.024).

As illustrated in Figure 4, while knee extensors, knee flexors, and plantar flexors exhibited significant time effects in both groups, the significant interaction effects indicate that the IASTM group demonstrated markedly greater improvements. Specifically, knee extensor strength increased by 37.5% in the IASTM group compared to no change in the sham group, knee flexor strength improved by 37.5% in the IASTM group versus 12.5% in the sham group, and plantar flexor strength increased by 33.33% in the IASTM group compared to 11.11% in the sham group, highlighting the superior effectiveness of IASTM in enhancing these strength measures.

Results of a mixed ANOVA for lower limb muscle strength values. A significant time × group interaction effect was observed for knee flexors, extensors, and plantar flexors, showing greater strength improvement in the instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization (IASTM) group over time. The solid line represents the IASTM group; the dashed line represents the sham group. * indicates a significant time effect.

The analysis of STS vGRF variables and COP measures revealed no significant effects for time, group, or the time × group interaction (P > 0.05 for all variables and conditions).

5. Discussion

This study examined the effects of IASTM on lower limb strength and biomechanical performance during the STS movement in patients with KOA. While IASTM is primarily used for soft tissue mobilization and pain reduction, its potential to influence muscular strength and functional tasks such as STS remains an area of growing interest. Our findings indicate that IASTM, compared to a sham treatment, significantly improved knee extensor, flexor, and plantar flexor strength. However, it did not produce significant changes in the kinetic parameters of the STS task, specifically vGRF or COP measures. These results suggest that while IASTM enhances muscle strength, its impact on biomechanical performance during functional movements remains limited.

The significant improvements in knee extensor, flexor, and plantar flexor strength observed in both groups — exercise with sham IASTM and IASTM combined with exercise — confirm that exercise therapy alone is effective in promoting strength gains. However, the greater improvements in the IASTM group suggest that incorporating soft tissue release into exercise therapy enhances these effects. This observation aligns with previous research, which has shown that IASTM and soft tissue release techniques, such as foam rolling, can increase muscle strength and improve functional performance (25, 39, 40). For instance, prior studies have reported significant increases in peak quadriceps strength and the quadriceps-to-hamstring strength ratio following IASTM compared to hold-relax and strain-counterstrain techniques (25). Additionally, total-body self-myofascial release using foam rollers has been found to be more effective than dynamic warm-ups in improving performance metrics such as vertical jump height, standing long jump distance, agility, bench press strength, and sprint performance in healthy individuals (40). Furthermore, a systematic review supports the efficacy of IASTM in increasing strength in patients with conditions such as lateral epicondylitis and carpal tunnel syndrome, highlighting its potential benefits across various musculoskeletal disorders (39).

The mechanisms underlying these improvements likely involve increased blood flow, reduced muscle stiffness, enhanced tissue extensibility, and diminished pain — all of which contribute to enhanced muscle force generation (15-17, 25, 39, 40). These physiological adaptations create a more favorable environment for muscle activation and strength development, explaining the improvements observed in this study. While significant gains were noted in knee extensors, flexors, and plantar flexors, dorsiflexor strength showed a trend toward improvement but did not reach statistical significance. This may be attributed to the limited sample size, as a larger cohort could reveal significant changes in dorsiflexor strength, further supporting the effectiveness of IASTM and exercise therapy in targeting multiple muscle groups affected by KOA.

Despite these promising strength improvements, the absence of significant changes in STS kinetic measures, such as vGRF or COP, highlights an important distinction — enhanced muscle strength does not necessarily translate into improved functional performance. The STS task is a complex movement that requires not only muscle force production but also coordinated neuromuscular activation, balance, and postural control (4-10). While IASTM appears to facilitate muscle strength gains, it may not adequately address neuromuscular coordination, proprioceptive deficits, or intersegmental control, which are essential for optimizing STS biomechanics. Additionally, structural joint changes commonly seen in KOA — such as cartilage degeneration, joint instability, and osteophyte formation — may continue to impair movement efficiency, limiting the translation of strength gains into functional improvements. These findings suggest that while IASTM contributes to muscle strength gains, a more comprehensive rehabilitation approach incorporating neuromuscular training or proprioceptive exercises may be necessary to achieve meaningful improvements in STS performance.

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. The intervention consisted of four IASTM sessions over two weeks, a duration selected based on prior evidence demonstrating immediate or short-term benefits for clinical symptoms such as pain relief and improved range of motion and function (23-26). Although these sessions were sufficient to produce significant strength improvements, they may have been insufficient to elicit measurable changes in STS biomechanics. Future research should explore longer treatment durations or higher session frequencies to determine whether additional sessions yield greater functional benefits. Additionally, follow-up assessments were conducted only 48 hours post-treatment. Future studies should include extended follow-up periods to evaluate the sustainability of strength improvements and potential delayed functional adaptations.

This study focused on the kinetic parameters of STS, but kinematic and electromyographic analyses were not included. Investigating muscle activation patterns, movement coordination, and joint kinematics could provide deeper insights into the mechanisms through which IASTM influences functional performance. Furthermore, the study included only individuals with moderate KOA, limiting generalizability to patients with mild or severe KOA. Future research should examine IASTM’s effects across different KOA severity levels to determine its broader clinical applicability.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that IASTM effectively enhances lower limb muscle strength, particularly in the knee extensors, flexors, and plantar flexors, in patients with moderate KOA. However, these strength gains did not translate into significant improvements in the kinetic aspects of STS performance, including vGRF and COP. These findings suggest that while IASTM is a promising intervention for improving muscle strength in KOA, it may require additional sessions or integration into a comprehensive, multifaceted rehabilitation program to achieve meaningful functional improvements.