1. Background

The relative and absolute number of older adults is noticeably increasing worldwide. Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the older adult population is projected to rise from 12% to 22%, reaching 2 billion people (1). Studies suggest that over the next 40 years, the global population aged 65 and older will double. Of this increase, 52% will reside in Asian countries, and 40% in developed nations. According to international projections, by 2040, the older adult population in Iran will grow faster than in other regions and even surpass the global average growth. Moreover, by 2045, it will exceed the average growth in Asia (2).

Aging is a gradual and slow process characterized by the continuous decline of natural physiological functions over the lifespan of living beings (3). As age increases, the body's resilience decreases, making it more vulnerable to age-related diseases such as neurological disorders and cancer, thereby increasing the risk of death (4). Significant physical, psychological, and social changes occur during old age. Specifically, older individuals increasingly face a decline in their functional abilities, which leads to a loss of independence (5). Aging is a sensitive period in life accompanied by profound physical, psychological, and social changes. As people age and enter old age (from 75 years onwards), psychological and social activities diminish, potentially resulting in feelings of hopelessness and isolation (2). Perceived physical fatigue is highly prevalent among older adults, especially women, and is strongly associated with age, physical and cognitive performance, physical activity, and several health conditions (6). Fatigue is a very common symptom in the older adult population and a significant risk factor for loss of function, disability, future diseases, and mortality (7). Fatigue, as an independent concept separate from daily activities and lifestyle, may fail to adequately reflect its symptoms and effects. In other words, understanding fatigue requires examining it within the context of various life aspects and daily habits to better comprehend its real impact (6). Fatigue is often considered a typical manifestation of aging, a symptom that reveals the effects of aging on the organism (8). Fatigue is strongly linked to poor physical performance (9) and serves as a robust predictor of numerous adverse outcomes in older adults, including hospitalization, increased use of healthcare services, incident disability, and mortality (10).

The prevalence of fatigue is estimated to range from 6% to 45% among community-dwelling older adults (8). Fatigue does not receive as much attention as comparable conditions like pain and depression. These three issues — fatigue, pain, and depression — are common in older age and can lead to adverse clinical outcomes. Hence, fatigue, like pain and depression, requires greater consideration in clinical treatments (11). Psychiatric and cognitive disorders are among the challenges interfering with active aging. Over 20% of adults aged 60 and older suffer from mental or neurological disorders unrelated to headaches, accounting for 6.6% of overall disability in this age group (12). A wide range of mental disorders exists, ranging from mild personality changes to severe disruptions in mental activity (1). Research shows that 13% of older adults with anxiety disorders also experience depression, while 36% of depressed patients have comorbid anxiety disorders (12). Psychological distress is largely defined as a state of emotional pain and suffering, consisting of symptoms of depression and anxiety, often accompanied by physical symptoms (13). Psychological support facilitates adaptation as a vital element of palliative care, which, as defined by the World Health Organization, involves comprehensive support to alleviate suffering and improve the quality of life for patients (14). To this end, interventions focused on verbal emotional self-disclosure have been designed as techniques for expressing or discussing feelings. These therapies are based on the premise that expressing emotions can enhance individuals' psychological well-being (15). Verbal emotional self-disclosure is a technique that encourages individuals to privately write or talk about a traumatic, stressful, or upsetting event, usually from the past (16). The content and structure of verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions can vary greatly, making evaluations complex. For instance, the session length, delivery frequency, and the subject of disclosure can differ (14).

Reminiscence therapy and emotional self-disclosure can foster positive emotions, such as happiness. However, enhancing deeper variables like quality of life, which involves multiple factors, requires fundamental, long-term interventions that address the primary needs of older adults. Therefore, it is recommended to use verbal emotional self-disclosure to promote positive emotions among older adults. One of the psychological interventions that can impact the quality of life for older adults is verbal emotional self-disclosure.

2. Objectives

This study aims to investigate the comprehensive effects of this intervention on the dimensions of physical fatigue and psychological distress in older women residing in nursing homes.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Method

This applied study employed a quasi-experimental design with a pretest-posttest and a control group. The research design involved one independent variable (verbal emotional self-disclosure) and two dependent variables (psychological distress and physical fatigue).

3.2. Participants

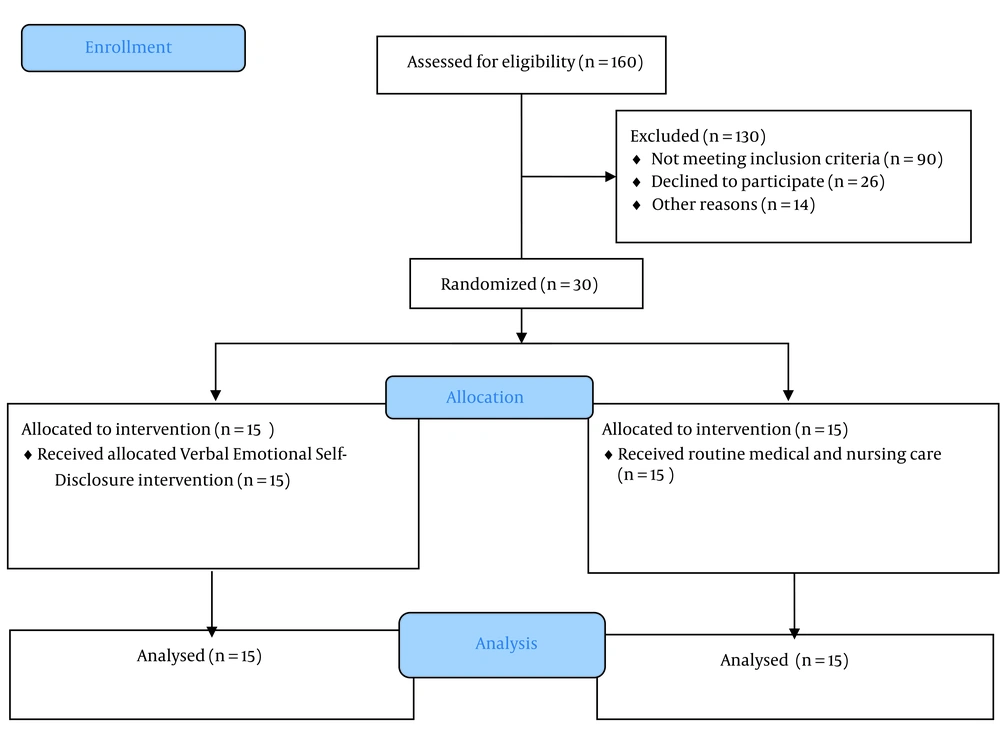

The research population consisted of all older women residing in a nursing home in Qods Town in southern Tehran in 2024. The total number of older women in the nursing home was 160. A total of 160 women participants were selected based on the inclusion criteria and were randomly assigned into two intervention and control groups using permuted block randomization (each with 15 participants, Figure 1). The sample size was estimated using the NFleiss sample size estimation equation (17), where β = 0.95, P0 = 0.90.5, P1 = 0.96, r = 0.90, and α = 0.05. Accordingly, considering a 10% sample attrition rate, the sample size in each group was estimated to be 32 people. The sample size for this study was 30 older women, with each group consisting of 15 participants, residing in the Qods nursing home.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Being literate, (2) not taking medications for anxiety, depression, or stress, and (3) not having hearing problems. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Missing two or more intervention sessions, (2) taking sedative or anxiety medications, (3) having cognitive disorders based on a psychiatrist interview and the mini mental state examination (MMSE) test (18), and (4) receiving other psychological treatments or counseling during the study period.

3.3. Instruments

3.3.1. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale

This scale, developed by Lovibond and tested on a large human sample by Crawford and Henry, assesses psychological distress. It contains 21 items divided into three subscales: Depression, anxiety, and stress (DASS-21), with each subscale measured by seven items scored on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 3. Each subscale has a maximum score of 21. The scores on each subscale are categorized as follows: Normal (0 - 4), moderate (5 - 11), and severe (≥ 12) (19). The scale’s reliability was analyzed by Antony et al. through factor analysis, confirming the existence of three factors: Depression, anxiety, and stress (20). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for these subscales were reported as 0.76, 0.83, and 0.81, respectively.

3.3.2. Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory

This instrument, developed by Smets et al., consists of 20 items across five subscales: General fatigue (4 items), physical fatigue (4 items), reduced activity (4 items), reduced motivation (4 items), and mental fatigue (4 items). The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) is used to assess fatigue comprehensively in both patients and healthy populations. The items are scored on a five-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 ("yes, that is true") to 5 ("no, that is not true"). High scores represent more fatigue (21). This study used only the physical fatigue subscale. The reported Cronbach’s alpha for the MFI in this study was 0.81.

3.4. Intervention Program

Verbal emotional self-disclosure offered the older adults the opportunity to talk freely about their problems, negative and worrisome feelings, and stressful and traumatic events they had experienced. The intervention program was developed based on prior studies (22, 23) on verbal emotional self-disclosure (Table 1).

| Session | Goal and Content | Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introducing group members to each other, establishing mutual relationships between the counselor and participants, and introducing the primary and secondary objectives of the program | Administering pre-tests |

| 2 | Increasing motivation for participation throughout the treatment, presenting the treatment protocol, and defining treatment goals | - |

| 3 | Introducing the three components of emotional experiences, and introducing types of expressed emotions, such as (criticism, demand, intense emotional involvement, positive opinions, and warmth) | Explaining characteristics of individuals with high and low (positive and negative) emotional expressiveness |

| 4 | Teaching emotional awareness and styles of emotional expression, control, and ambivalence | Discussing ways to express emotions |

| 5 | Expressing emotions through speech | Freely expressing emotions and examining the effects of this expression on mental and psychological states |

| 6 | Discussing the open/free expression of positive and negative emotions and their effects on self and others | Expressing emotions like sadness, happiness, and anger |

| 7 | Encouraging the participants to engage in emotional self-exploration and address suppressed emotions | Teaching the participants to focus on emotionally impactful events and express their feelings |

| 8 | Recognizing behaviors influenced by emotions | Teaching proper emotional expression through effective discussions |

| 9 | Repairing damaged emotions through real-life scenario practice | Discussing the experience of uncomfortable emotions |

| 10 | Examining changes in the participants' perspectives on emotions such as joy and sadness in life | Encouraging the participants to share joyful memories with positive emotions |

| 11 | Helping the participants understand the impact of emotions on their experiences | Experiencing emotions and reflecting on their influence on thoughts and the mind |

| 12 | Reviewing the instructed materials, addressing remaining questions, and preparing the group for the end of sessions | Practicing the expression of positive emotions and managing negative emotions |

3.5. Data Collection Procedure

The participants in this study were 30 older women residing in a nursing home in Qods Town in Tehran, who were selected using convenience sampling. Subsequently, the participants were randomly assigned to two groups: Intervention and control (each with 15 participants). The study was conducted in two phases: Pre-test and post-test. In both phases, the participants completed the research questionnaires. The participants in the intervention group attended a structured group program, whereas the control group received no intervention. During the intervention sessions, the control group received the usual medical, nursing, and recreational care. The intervention program for the intervention group included 12 sessions, each lasting 60 minutes. These sessions were conducted twice weekly (on Sundays and Tuesdays) at 9:00 AM in an outdoor setting within the nursing home. Therapeutic interventions were provided by a rehabilitation psychologist in collaboration with the center's psychiatric nurse. One week after the intervention, the post-test phase was conducted, and questionnaires were collected. After completing the intervention sessions and collecting the post-test questionnaires, 6 sessions of the verbal emotional self-disclosure program were held for the control group.

3.6. Data Analysis

The data collected from the questionnaires were analyzed with SPSS-26 software using descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum scores, and inferential statistics, including multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

3.7. Complying with Ethical Guidelines

The protocol of this study was approved by the Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research with code: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1403.092. To comply with the ethical principles of voluntary participation, written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

4. Results

Table 2 shows the participants’ demographic characteristics. As can be seen, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the demographic variables.

| Variables | Control | Intervention | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Older women age (y) | 79.18 ± 1.21 | 78.12 ± 1.18 | 0.34 b |

| Number of children | 0.29 c | ||

| One or two child | 11 (74) | 10 (66) | |

| No child | 4 (26) | 5 (34) | |

| Education | 0.39 c | ||

| Elementary school (6th grade) | 9 (60) | 9 (60) | |

| Diploma degree | 4 (26) | 3 (20) | |

| Undergraduate | 2 (14) | 3 (20) | |

| Marital status | 0.84 c | ||

| Married | 3 (20) | 2 (14) | |

| Single | 12 (80) | 13 (86) |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b Independent t-test.

c Chi square.

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the research variables in the pre-intervention and post-intervention phases. Additionally, the table includes skewness and kurtosis indices to examine the normality of the data distribution. As observed, the skewness values of the variables, with absolute values less than 3, indicate that the skewness of the research variables is within the normal range. Similarly, the absolute values of the kurtosis index are less than 10, signifying that the kurtosis of the variables is also within the normal range. These data confirm the normal distribution of all variables in both the pre-intervention and post-intervention phases for the two intervention and control groups.

| Variables | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Intervention | 11.73 ± 2.43 | -0.36 | 0.32 | 10.20 ± 2.33 | -0.17 | 0.42 |

| Control | 11.00 ± 2.23 | -0.71 | 0.88 | 10.87 ± 2.26 | -0.52 | 1.00 |

| Stress | ||||||

| Intervention | 11.93 ± 1.75 | -0.77 | 0.57 | 10.40 ± 1.24 | -0.32 | 0.65 |

| Control | 12.60 ± 1.35 | -0.11 | -0.74 | 12.80 ± 1.37 | -0.43 | -0.35 |

| Depression | ||||||

| Intervention | 11.13 ± 1.84 | 0.27 | 0.56 | 9.73 ± 1.66 | 0.57 | 0.70 |

| Control | 11.33 ± 2.02 | -0.13 | 0.66 | 11.20 ± 1.89 | 0.04 | 0.68 |

| Multidimensional fatigue | ||||||

| Intervention | 12.60 ± 1.99 | -1.24 | 0.14 | 11.33 ± 1.75 | -0.43 | -0.22 |

| Control | 12.87 ± 1.88 | -0.94 | 0.36 | 12.73 ± 1.71 | -0.75 | 0.28 |

As can be seen from Table 4, after controlling for the pre-test effect, there were significant differences between the verbal emotional self-disclosure and control groups in terms of anxiety (F = 62.19; P = 0.001), stress (F = 106.24; P = 0.001), and depression (F = 71.18; P = 0.001), confirming that verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions reduce psychological distress in older women. This finding shows that significant changes occurred in the psychological distress of older women as a result of the verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions. The Eta coefficients also show that the effect sizes of the intervention are as follows: 0.71 for anxiety, 0.81 for stress, and 0.74 for depression. Furthermore, after controlling for the pre-test effect, there was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of physical fatigue (F = 42.06; P = 0.001), indicating that verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions reduce physical fatigue in older women. Thus, a significant change with an effect size of 0.60 occurred in the physical fatigue of older women as a result of the verbal emotional self-disclosure intervention.

| Sources | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | ||||||

| Anxiety | 13.08 | 1 | 13.08 | 62.19 | 0.001 | 0.71 |

| Stress | 25.06 | 1 | 25.06 | 106.24 | 0.001 | 0.81 |

| Depression | 11.29 | 1 | 11.29 | 71.18 | 0.001 | 0.74 |

| Multidimensional fatigue | 10.23 | 1 | 10.23 | 42.06 | 0.001 | 0.60 |

| Error | ||||||

| Anxiety | 5.26 | 25 | 0.21 | - | - | - |

| Stress | 5.89 | 25 | 0.23 | - | - | - |

| Depression | 3.96 | 25 | 0.15 | - | - | - |

| Multidimensional fatigue | 6.56 | 27 | 0.24 | - | - | - |

| Total | ||||||

| Anxiety | 34.80 | 30 | - | - | - | - |

| Stress | 41.28 | 30 | - | - | - | - |

| Depression | 33.92 | 30 | - | - | - | - |

| Multidimensional fatigue | 44.43 | 30 | - | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: SS, sum of squares; df, degrees of freedom; MS, mean squares; F, F-value; η2, Eta squared (effect size).

5. Discussion

The findings confirmed that verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions reduced psychological distress in older women, and significant changes occurred in the psychological distress of older women who attended the verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions. Multiple studies have shown that the impacts of disclosing personal experiences related to psychological problems involve both potential benefits and drawbacks. Positive effects of disclosure include the reduction of negative self-image (self-perception) (24, 25). In addition, improved quality of life and increased personal empowerment (26), as well as increased social support, are other positive outcomes of experience disclosure. Research results indicate that written self-disclosure can reduce negative emotions but does not improve positive emotions (27). In this study, verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions for older adults were conducted using a memory recall program. The findings suggested that talking about the past improves older adults’ inner feelings and reminds them of a more active period in their lives. This positive experience leads to a better self-assessment of their health and quality of life, and they engage more energetically in their daily activities. Furthermore, older individuals may experience difficulties in filling their leisure time due to anxiety, depression, and loneliness resulting from retirement and economic problems. Verbal emotional self-disclosure helps them express their positive and negative feelings, which can shift their attitudes. Individuals may think that sharing negative experiences might make others dislike them, and thus they may do their best to present themselves in the best possible way (28). From a Freudian perspective, talking about sorrowful events and problems can lead to catharsis and help individuals relieve stress (27). Previous studies have also shown that self-disclosure is beneficial for individuals with emotional problems in maintaining better mental health (29), and it helps reduce perceived stress (28) and anxiety (30). Previous studies have shed light on the relationship between negative emotions and self-disclosure. A study concluded that when individuals experience negative emotions, they tend to suppress or reshape them rather than talk about these feelings, in an attempt to cope with their issues and avoid negative emotions, resulting in a sense of calm and comfort (31). However, it has also been shown that this strategy consumes significantly more energy and reduces self-control. Additionally, individuals tend to change themselves or their environment until negative emotions are converted to positive feelings (32). A better way to cope with and overcome negative emotions is to fully accept these feelings without trying to avoid them (31). Overall, individuals tend to actively avoid negative emotions when experiencing them and strive to maximize positive emotions (32). Consequently, these studies suggest that instead of avoiding negative emotions, verbal emotional self-disclosure may be a more effective coping strategy to manage negative emotions and also reduce both negative emotions and psychological distress in older women.

The verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions reduce physical fatigue in older women. Moreover, significant changes occurred in the fatigue of older women as a result of verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions. Accordingly, the theory of physical weakness suggests that stress and other psychological disorders, along with specific psycho-physiological disorders, lead to weakness in specific bodily functions. This system becomes vulnerable to future stress, even mild and moderate stress. According to this theory, illness arises from the interaction between an individual's physiology and stress (33). One study examined the participants’ emotional experiences from various aspects, including physiological outcomes (such as bodily changes), immunological outcomes (e.g., immune system functioning), objective and subjective health measures (such as blood pressure or pain), and psychological outcomes (such as mood and emotional state). In other words, this study examined the impact of emotional disclosure on various aspects of human health and performance (16).

Verbal emotional self-disclosure has played a significant role in the interpersonal relationships of older adults, fostering better understanding and intimacy with other older individuals. In addition, this intervention program enhanced various aspects of their psychological adaptation, such as mental health, competence, self-efficacy, and social adjustment. During the verbal emotional self-disclosure intervention, the older adults experienced a reduction in stress caused by negative emotions, a decrease in anxiety, and a short-term improvement in their emotional impact, which ultimately contributed to a long-term relapse of their psychological problems. Moreover, verbal emotional self-disclosure, through receiving support, strengthened their relationships and intimacy with others, improving the psychological outcomes that were deeply rooted in their self-image, such as the revitalization of self-worth after disclosure. Using verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions with a memory recall program, this study showed that reminiscence is a part of the natural life cycle for older adults, preparing them to reduce psychological distress. Group-based structured reminiscence, through improving depression, anxiety, and stress, contributes to enhancing cognitive and physical states in older individuals. This study was conducted on literate older women residing in nursing homes in the city of Qods, Tehran. This may limit the generalizability of the results to less developed areas, such as rural cities and villages. In addition, the study examined the effectiveness of verbal emotional self-disclosure in women. Expressing emotions varies depending on gender, culture, and life beliefs; therefore, emotional self-disclosure may differ for older men. Failure to implement a follow-up phase may limit the sustainability of the intervention. In future research, it is recommended that verbal emotional self-disclosure interventions be used in memory recall programs to prepare older adults for death, resolve past conflicts, achieve existential completeness, and find meaning in life and positive self-affirmation.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings from the present study indicated that the verbal emotional self-disclosure intervention led to the development of intimate relationships and adaptive coping with psychological distress and traumatic events, including negative thoughts in older adults. Ultimately, the findings indicated that verbal emotional self-disclosure reduced psychological distress in older adults by breaking the process of inhibition, thereby alleviating their fatigue. As a result, new cognitive changes occurred in their minds, where expressing emotions and feelings through words led to a reevaluation of their thoughts.