1. Background

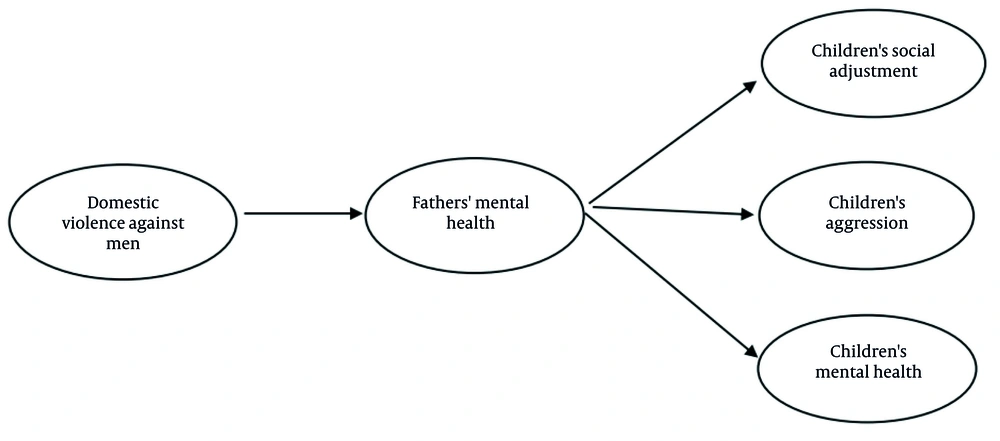

Domestic violence against men has emerged as a significant concern within the family environment in recent years (1). This form of domestic violence does not have a clear and distinct definition compared to violence against women; it encompasses any intentional mistreatment of a spouse, which includes sexual abuse (any form of unusual and abusive sexual relations), emotional abuse (acts of mistreatment and humiliation towards a spouse), and physical abuse (hitting and causing harm to a spouse) (2, 3). Regarding the prevalence of domestic violence against men in Iran, there is insufficient data; however, it appears to be quite common. A study conducted in the city of Mashhad, which examined 394 men, found that approximately 25% of participants reported experiencing moderate to severe domestic violence, with the most frequently reported form being psychological abuse (4). Notably, the prevalence of this type of violence has been observed to be higher compared to domestic violence against women (1, 2, 5). Due to the complexity and multifaceted nature of domestic violence, various psychological explanations have been proposed. The most significant of these include a spouse’s desire to control and dominate the other, the presence of anger and dissatisfaction, deficiencies in emotional management skills, and a lack of mutual understanding and empathy (1, 6). Domestic violence against men can have detrimental effects on their mental and physical health (7). Impaired mental health means that these men not only experience emotions such as anxiety (ANX), depression (DEP), and stress more intensely than others, but the increased anger and violence stemming from domestic violence can lead to a heightened risk of sexual conflicts and violent behavior in other relationships (8). Additionally, past studies have observed an increased risk of physical ailments (such as respiratory issues, muscular pain, and a higher likelihood of cardiovascular diseases) and psychological issues (self-harming behaviors such as suicide and substance abuse), as well as a decrease in quality of life among men who experience domestic violence (9-11), which can adversely affect spousal and family relationships. One of the negative consequences is its impact on children’s attitudes and behaviors. In other words, low mental health in fathers can significantly affect their children’s social adjustment, mental health, and increase the prevalence of aggression among them (8, 12). Despite various past studies, information regarding the underlying mechanisms of the impact of domestic violence against men on social adjustment, mental health, and aggression in their children remains unclear. In this context, a conceptual model was developed and illustrated based on a review of the literature (Figure 1).

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to address the question of whether the mental health of fathers can serve as a mediating variable on the impact of domestic violence against men on their children’s social adjustment, aggression, and mental health.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

The present study utilized a cross-sectional correlational design to analyze structural relationships through path analysis. The sample comprised married men (aged between 30 to 60 years) with children aged 5 to 12 years visiting health centers in Semnan city in 2023. They were required to provide informed consent, possess at least 8 years of education, and have no visual or auditory impairments, excluding those with psychiatric disorders or substance abuse histories (based on medication history). Before administering the instruments to the participants, a researcher with a master’s degree in clinical psychology introduced herself to each participant and requested them to complete the informed consent form. After explaining the research objectives and assuring confidentiality regarding the issues raised by the researcher, the instruments were provided to the men for their responses, which were collected after 45 minutes.

3.2. Sample Size Estimation

According to the Tabachnick and Fidell formula (N ≥ 104 + M), the sample size should exceed 109 individuals (13). In this study, a sample size of 200 was considered.

3.3. Variables and Measurement

In this study, four instruments were used for data collection.

3.3.1. Demographic Checklist

This checklist was used to gather background information such as age, gender, education level, marital status, and other relevant entry criteria.

3.3.2. Domestic Violence Questionnaire Against Men

This questionnaire, consisting of 44 items, measures violence against men, with 20 items assessing emotional or psychological abuse (questions 1 to 20), 10 items assessing physical abuse (questions 21 to 30), and 14 items assessing sexual abuse (questions 31 to 44). Each item is scored on a four-point Likert scale from never (0) to always (3), with higher scores indicating more experience of domestic violence. The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the questionnaire was reported as 0.92, with a test-retest reliability of 0.98 (14).

3.3.3. Social Adaptation Scale

This scale was used to assess social maladjustment in children. It evaluates interpersonal relationships across various roles, including emotions, satisfaction, conflict, and functioning. The questionnaire consists of 52 questions across six role domains (work, social activities and leisure, family relationships, spousal roles, parental roles, and family unit membership). In this study, only questions 13 to 27 (school adaptation and adaptation with friends) were completed, as the other questions were not relevant to the children in the sample, with higher scores indicating greater social maladaptation. The reliability of the questionnaire was reported as 0.48 using Cronbach’s alpha and 0.80 for test-retest reliability (15). Previous studies in Iran reported the highest reliability values in adaptation and leisure (0.50) and the lowest in family relationships (0.46) (16).

3.3.4. Aggression Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents

This self-report tool assesses various situations that provoke anger, as well as the intensity of anger and aggression and social skills in children. It was developed by Nelson and Finch in 2000 and this questionnaire is designed for ages 6 to 16, including students from elementary to high school levels, normed in Iran by Majdian in 2008. The questionnaire consists of 39 items assessing anger across four dimensions: Frustration (11 items), physical aggression (9 items), peer relationships (9 items), and relationships with authority figures (10 items), using a four-option Likert scale: Not at all, bothers me, really upsets me, and makes me angry. The minimum and maximum scores for each individual range from 39 to 156, with higher scores indicating greater anger. The cutoff score for aggression in this test is 8. In research conducted by Nelson et al. on 1,604 students, the test-retest reliability ranged from 0.65 to 0.75, with reliability coefficients between 0.85 and 0.86 and validity for the four subscales at 0.93 (17).

3.3.5. SCL-25 Mental Health Assessment Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents

This questionnaire, developed by Najarian and Davodi (2001) as cited by Tanhaye Reshvanloo and Saadati Shamir (18), consists of 25 items that assess mental health and symptoms of psychological disorders. It is rated on a five-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). The SCL-25 is recognized as a mental health questionnaire, measuring psychological distress. Interpretation of scores indicates that lower scores reflect better mental health, while higher scores indicate poorer mental health. The questionnaire includes nine subscales [somatic complaints (SOM), obsessive-compulsive (DOC), interpersonal sensitivity (INT), DEP, ANX, phobic ANX (PHOB), paranoid ideation (PAR), psychoticism (PSY), and additional distress (ADI)]. Notably, the reliability of the questionnaire in Iran was reported with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.801 (18).

3.3.6. Adult Mental Health

This questionnaire includes 14 questions and is based on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), with questions such as "the feeling that you have work or something important to offer to society". It assesses the mental health of adults. A score between 28 and 56 indicates a moderate level of mental health. A score above 56 indicates a high level of mental health. A score between 14 and 28 indicates a low level of mental health. The calculated Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this questionnaire was estimated to be above 0.7 (19).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The study confirmed data normality and the absence of outliers, with a Factorability Index of 0.782 (approx. chi-square; 243.556, P-value; 0.000, Df; 10), meeting the criteria for factor analysis. Statistical analyses, including the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and box plots, were employed to assess data integrity. Goodness of fit and model validity were evaluated using various indices, while structural equation modeling was applied to test research hypotheses, with data analyzed using Amos 22.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted to obtain a master’s degree in clinical psychology, with an ethical code of IR.IAU.SEMNAN.REC.1402.021. To uphold professional ethics in research, written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The procedures for implementing the study were explained to the participants, who were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Emphasis was also placed on the confidentiality of the information, with participant data and research results being kept confidential for three months following the publication of the results by the project implementer.

4. Results

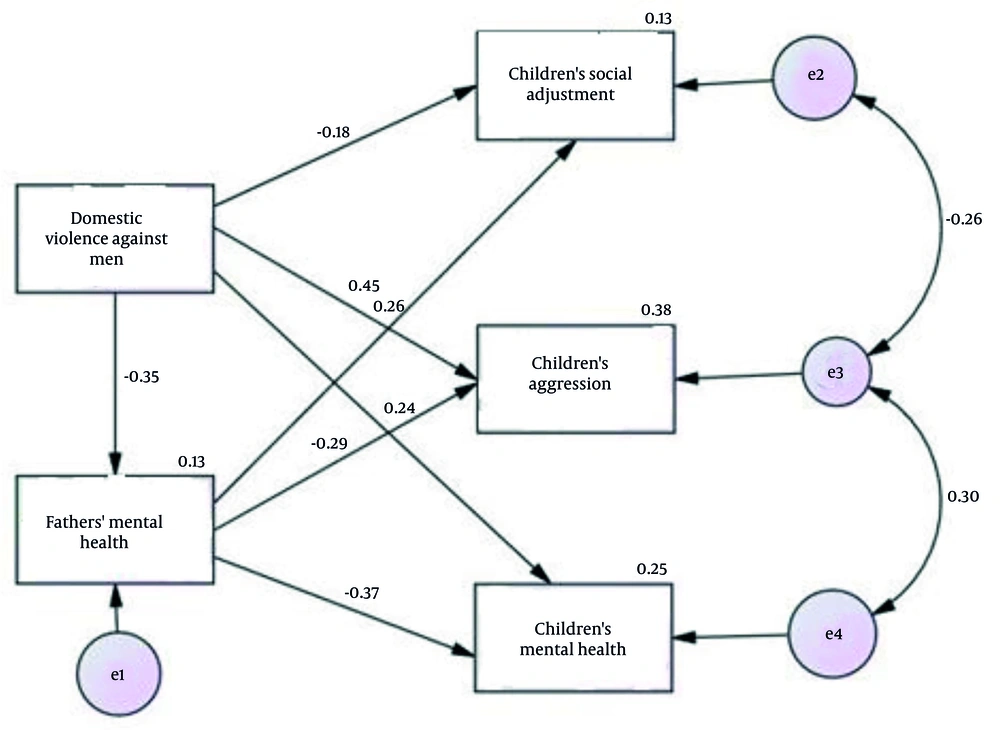

The findings from descriptive data of 200 married men visiting health centers in Semnan city, aged between 30 to 60 years, indicate that the majority of respondents (49%) are aged between 35 to 50 years, while the smallest group (18.5%) is under 35 years. The majority of respondents (50%) hold a bachelor’s degree, whereas the least (5.5%) have a master’s degree or higher. Descriptive information and the correlation between the main variables of the study represent a significant correlation among all main variables of the study at a level of P < 0.01. The skewness and kurtosis of the data fall within the specified range, and the normality assumption of the data is confirmed according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (Table 1). Information related to the model fit indices was declared acceptable and confirmed (Table 2). The Durbin-Watson statistic ranges from 0 to 4. Given that the value of this statistic was 2.14, the assumption of independence of errors is met, and regression analysis can be performed. Collinearity indices of Table 3 indicate that there is no collinearity between the predictor variables, and the results are reliable. The results of the path analysis and its coefficients demonstrated that domestic violence against men has a direct effect on children’s aggression, adaptability, and mental health. However, after considering men’s mental health as a mediating variable, the impact of domestic violence against men on children’s aggression, adaptability, and mental health is reduced but remains significant, confirming the mediating role of adult mental health in the effect of domestic violence against men on children’s aggression, adaptability, and mental health (P < 0.05) (Figure 2 and Table 4).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Kolmogorov-Smirnov | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic violence against men | 1 | - | - | - | - | 43.2150 ± 15.64778 | 0.543 | 0.267 | 0.086 | 0.001 |

| Children’s aggression | 0.551 a | 1 | - | - | - | 68.4250 ± 17.83437 | 0.249 | -1.034 | 0.096 | 0.000 |

| Children’s social adjustment | -0.271 a | -0.425 a | 1 | - | - | 49.5750 ± 10.93353 | 0.208 | -1.035 | 0.127 | 0.000 |

| Fathers’ mental health | -0.355 a | -0.445 a | 0.322 a | 1 | - | 47.7400 ± 10.32402 | -0.149 | -0.803 | 0.060 | 0.076 |

| Children’s mental health | 0.374 a | 0.519 a | -0.263 a | -0.452 a | 1 | 39.6550 ± 16.20708 | 0.129 | -0.820 | 0.069 | 0.021 |

a P < 0.01.

| The Goodness of Fit | NNFI/TLI | NFI | RMSEA | PNFI | AGFI | GFI | TLI | IFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default model | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.069 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.960 | 0.996 | 0.996 |

| Acceptable ranges | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | < 0.08 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 |

| Models | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | Collinearity Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | B | t | P-Value | Tolerance | VIF | |

| Constant | 12.651 | 1.270 | - | 9.963 | 0.000 | - | - |

| Domestic violence | 0.129 | 0.028 | 0.315 | 4.671 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Father’s mental health | 0.679 | 0.200 | 0.243 | 3.394 | 0.001 | 0.846 | 1.182 |

a Dependent variable: Children’s social adjustment, children’s aggression, and children’s mental health.

| Independents | Direct | Indirect | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic violence against men | ||||

| Fathers’ mental health | - 0.35 | 0.00 | -0.35 | 0.44 |

| Children’s aggression | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.55 | 0.068 |

| Children’s social adjustment | -0.18 | -0.091 | -0.27 | 0.049 a |

| Children’s mental health | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.37 | 0.068 |

| Fathers’ mental health | ||||

| Children’s aggression | -0.29 | 0.00 | -0.29 | 0.103 |

| Children’s social adjustment | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.075 |

| Children’s mental health | -0.37 | 0.00 | -0.37 | 0.103 |

a P < 0.05.

5. Discussion

The study aimed to explore the mediating role of fathers’ mental health in the effects of domestic violence against men on their children’s aggression, adaptability, and mental health. The findings indicated that domestic violence against men negatively impacts their mental health, which in turn affects their children’s behavior and emotional well-being. While previous research has not specifically addressed this mediating role, it has shown that men who experience domestic violence often suffer from ANX, DEP, and stress. These emotional challenges can lead to increased anger and violence, heightening the risk of conflicts and violence in their relationships (20), ultimately diminishing their quality of life and physical health, and increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases, self-harm, and substance abuse (21).

Men who endure domestic violence frequently experience feelings of disrespect and a decline in self-esteem, which can disrupt their relationships with partners and family members (22). This struggle can hinder their ability to form and maintain healthy interpersonal relationships, often resulting in low mental health (23). Fathers with poor mental health can negatively influence their children’s behavior, as those with better mental health serve as positive role models, teaching children effective coping strategies for stress and psychological challenges. This positive influence can enhance children’s adaptability (24), communication skills, self-esteem, and social growth (25).

Social adaptability encompasses an individual’s ability to interact effectively with others, understand diverse perspectives, and navigate social environments. Children primarily learn these skills within their families. Healthy family relationships, characterized by respect, cooperation, and empathy, foster a child’s desire for connection and enhance their sense of community. Conversely, unhealthy family dynamics, such as violence or physical punishment, can lead to withdrawal and hinder a child’s ability to adapt socially. A mentally healthy child is expected to fulfill age-appropriate responsibilities, establish relationships, and demonstrate flexibility in various situations. These abilities are cultivated through education and guidance within the family, which serves as the primary nurturing environment. The home should be a safe space where children can express their interests and emotions without fear, seeking support from family members (26).

The consequences of domestic violence against either men or women in the presence of children are detrimental, leading to reduced mental health and social adaptability in children, as well as increased aggression. Children who exhibit high levels of aggression early in life are likely to continue this behavior into adolescence and adulthood (27). Some researchers argue that aggressive behavior is shaped by educational processes within the family, school, and society. Gaps in these processes can reinforce aggressive tendencies. Behavioral theorists suggest that aggressive behaviors are learned through imitation (28), while social theorists attribute aggression to a lack of interaction in high-stress environments. Fathers with strong mental health are better equipped to communicate with their children, fostering self-esteem and social development (29).

5.1. Conclusions

Overall, parents must recognize the sensitivity of their child’s mental health during formative years, as it can be easily influenced by their environment. Awareness of factors that may harm a child’s mental health is crucial for prevention.

5.2. Limitations

Limitations of the study include reliance on questionnaire data and a sample limited to men visiting health centers in Semnan, which may not represent all men in the region.

5.3. Future Research

Future research should consider clinical interviews and observations, as well as broader geographical contexts to enhance the generalizability of findings.