1. Background

By definition, retirement occurs when a person no longer participates in work activities because of increased age or the end of a duty period, and it should be considered as a new stage in the employee's life (1). In recent times, improved life expectancy, as well as interest in early retirement, have increased the number of individuals reaching retirement age (2, 3). Evidence shows that transitioning to retirement has clear effects on their; routine actions, social relations, family and social roles, self-confidence, and social supports (4). Therefore, retirement is a predictable event in the life stage which is accompanied by changes in financial and social status, and personal communication roles (5). Atchley believes that retirement is a process of transferring from one role to another, from employee which has its own norms, into a retired person with their own distinctive norms (6). Retirement is frequently accompanied by feelings of confusion, loss of income, lower social status, decreased self-confidence and discrepancies between what has happened and what was expected (7), as a result most retired persons are likely to experience stress in their life (8). It is accepted that retirement is a social phenomenon which needs a period of adjustment (9). The way in which an individual adjusts to the retirement process depends on various factors, such as their professional activities and physical condition (10). Nurses experience a number of severe stresses such as; role ambiguity, role conflict, and work pressure in the workplace. For some nurses, the retirement process is a way to improve their life and for some others may result in a life distraction (11).

Nurses form the core of the health care system (12), moreover, they are one of the most important human resources in the healthcare system (13). Many registered nurses are now approaching retirement age (14); however, one third of retired nurses experience problems with their adjustment to retirement (7). For some retired nurses, retirement may be a way to improve their self-care and life style, while others experience retirement as a period of non-adjustment (11). Results of research conducted by Andrews et al. in England showed that there are three main factors which affect adjustment in retired nurses; job related stresses, lack of flexible working hours, and salary. Furthermore, nurses need to pay attention to their physical and mental needs in order to adjust successfully to retirement (15). Results of a study conducted by Blakeley and Ribeiro in Canada found that using social support networks, developing new relationships, engaging in new activities, traveling, and keeping physically fit were effective measures for better adjustment in retired nurses (14).

Adjustment is a process that is consistent with the grounded theory approach, so this method was used to study the nurses' retirement process. In addition, adjustment to retirement can be influenced by both cultural and religious factors, while social and mental factors also have an effect on this phenomenon (16). Despite the influence of retirement on the individual, their family, and the economic life of society, it has not been widely discussed in previous studies. In this regard, there have been no comprehensive qualitative studies performed on retired nurses, and the majority of the studies on retirement have been conducted using a quantitative approach (8). Given the fact that the retirement phenomenon is multidimensional, interactive, and influenced by different physical, mental, and social factors, the best qualitative method for conducting this research was grounded theory. This approach explains both associated social processes and human interactions in related structures (17).

2. Objectives

This study was conducted in order to explore the adjustment process to retirement through an in-depth study of retired Iranian nurses.

3. Patients and Methods

This was a qualitative study based on grounded theory methodology which was performed using the proposed method of Strauss and Corbin (18).

3.1. Sampling and Data Gathering

A purposive sampling method was used, and this was followed by theoretical sampling (19). Purposive sampling of the participants, included key informants consist of retired nurses, and followed by research progression and analysis of the obtained data, theoretical sampling was used to develop the analysis. Twenty-three participants were recruited, including; 20 retired nurses (10 women, 10 men) from Semnan, Iran, aged between 50-60 years, who had had work experience for between 23 and 30 years. Individuals were selected if a period of 1 to 5 years had passed since their retirement. Moreover, three spouses of the retired nurses were invited to participate in this study. First names, addresses, and phone numbers of the retired nurses were obtained. Then, they were called by phone and the aim of the study was explained to them, if they accepted to participate in the study, an appointment was then set. Interviews were conducted in a park near the interviewe's home. In-depth and semistructured interviews were the main method used to collect the data. Qualitative data from the transcribed interviews and field notes were analyzed by making constant comparisons (18). The interviews began with a range of general questions (20) concerning how adjustment to retirement had occurred in the nurses. Then, more probing questions were asked in order to improve the depth of the interviews. The average duration of the interviews was between 40 minutes to 120 minutes. Additional data collection methods were also used, such as filed notes and memos which helped to enrich the data. Data gathering was continued until data saturation was reached (18, 21). Sampling continued until such time as no new data appeared about the study question, and the researchers were convinced that they had received theoretical saturation (18).

3.2. Data Analysis

The findings were analyzed according to the approach proposed by Strauss and Corbin (18). The data was collected, coded, and analyzed simultaneously from the beginning of the study. The data was coded in three stages; open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. These codes were used to provide a consistent, regular, and descriptive creation of a theory (18, 22). After transcribing the text of the first interview, meaningful components were identified with a label from the text's words or concepts (open coding). With open coding, the data was divided into separate parts. In order to obtain similarities and differences, the data was carefully investigated, and some questions which arose from the data, were then asked about the phenomena. In this way, conceptualization of the data as the first step in analysis of the data was accomplished. When a particular phenomenon was specified in the data, the concepts were classified around it. This allowed the codes related to an issue to be placed in a specific class, and a conceptual name which was more abstract than the set of those categories, was then considered for that specific class (18).

After writing the initial codes, the first categories were formed. By using the paradigm, paying attention to the phenomenon, determining causal conditions, context, action/interaction strategies, and resulting consequences, the data could be connected and axial coding performed. With axial coding and the creation of relationships between each category and its related subcategories, the gathered data could be related to each other. To form a theory, the concepts were systematically related to each other. By regularly selecting the original phenomenon, and relating it to other categories, the relationships between the categories were extended and amended, selective coding was developed, and finally the theory created.

3.3. Rigor

Four criteria, including; credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability or fittingness, were considered for the validity and credibility of the study. The purpose was to ensure that the study collected an accurate record of the participants' experiences (23). In order to assure the rigor of data analysis, the following steps were taken.

For credibility of the findings, the participants indicated whether the data and the results were an accurate, complete, interpretation of their experiences. Accordingly, a part of the interview was given to the participants. Scaling ideas were taken from the data and compared with the participants' feedback. Data credibility was checked through a review of the transcriptions by the participants as member checking. The participants were then asked to confirm if the findings were representative of their real world.

Dependability is a criterion used to determine the validity of the findings. Defining this criterion was obtained by prescription as soon as possible, through the opinions of colleagues and a restudy of all the data.

Conformability represents the stability and reliability of data over time and under identical conditions. Conformability was confirmed by peer checking, neutrality of the researchers, agreement on codes and themes, interviewing transcripts, codes and categories.

Transferability or fitness means fitness and mobility of the outcomes which can be used in similar situations. In this study to check transferability, we used interviews with various participants to provide direct quotes and examples to explain the rich data, followed by discussion and comparison of our findings with other studies.

3.4. Ethical Consideration

The research proposal was approved by the Research Committee of Tarbiat Modares University. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study by the first author. It was explained that their participation was voluntary, and they were given assurances with regard to the confidentiality and anonymity of data gathering. Finally, informed consent was obtained from those who agreed to be interviewed. The participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

4. Results

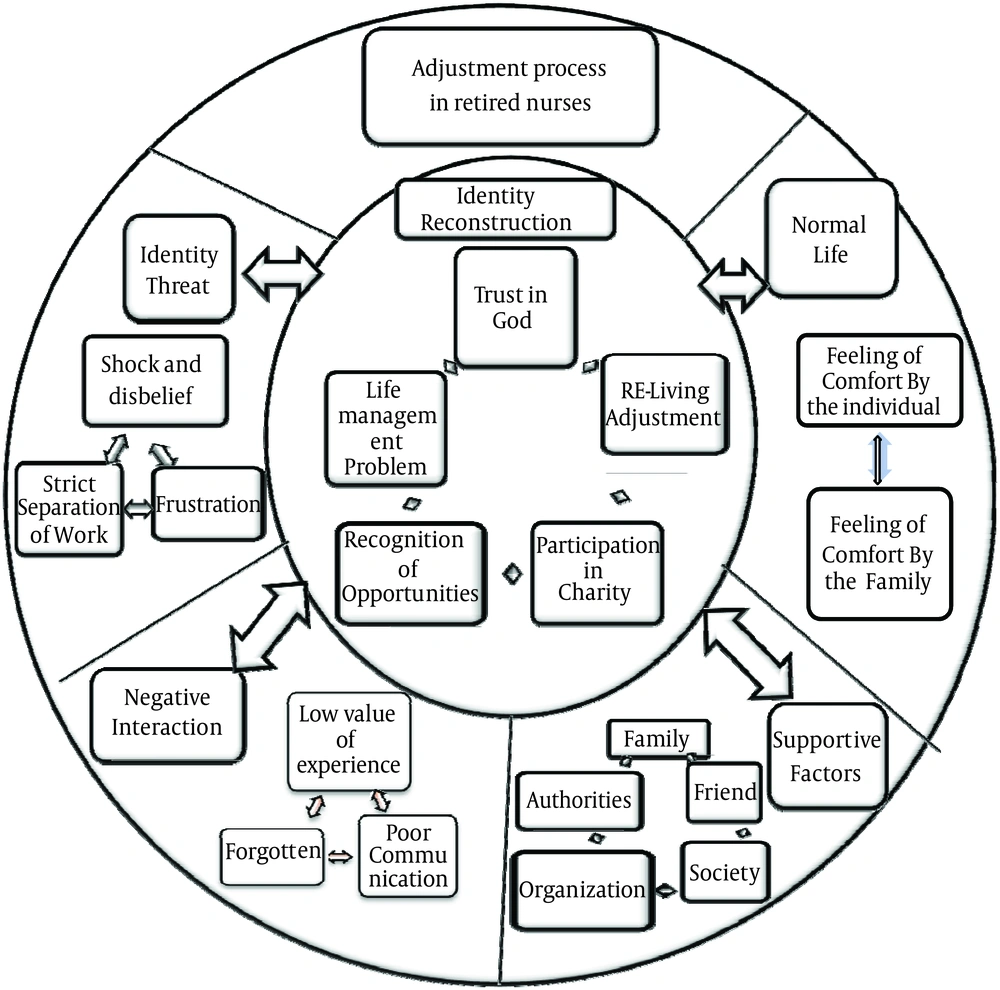

From the 23 interviews, 1 887 initial codes, 44 categories, and five axial categories were extracted. These categories included; “Identity threat”, “Negative interaction”, “Identity reconstruction”, “Supporting factors”, and "Normal life". The main concern expressed by the participants was "Identity threat". "Reconstructed identity" was a core variable that played an essential role in the adjustment process. According to the explanation associated with these concepts, a grounded theory of adjustment in retired nurses was extracted.

4.1. Identity Threat

Participants recognized identity threat (ie, shock and disbelief, strict separation of work and frustration), which developed during the adjustment process of retirement. Identity threat as an initial response, is associated with a fear of being different and feeling a loss of control. In addition, identity threat is associated with a fear of being labelled and it produces low cognitive and permanent changes in a person's lifestyle. Furthermore, ineffective communication and the negative reactions of others lead to greater threats to identity.

4.1.1. Shock and Disbelief

Not being ready, and being informed about their imminent retirement, had been a big shock for a number of retired nurses, and as a result many were unsettled for months. “It was too sudden. I was congratulated on my retirement, but it was incredible to me. Completely astounded” (Participant 13).

4.1.2. Strict Separation of Work

Leaving work meant leaving the habits formed over the years. The stress of job separation led to the feeling of being in a void, worry about not seeing friends and colleagues, separation from patients, crying, depression, and even a fear of death. “After 30 years of work, how can I stay in my house” (Participant 8).

4.1.3. Frustration

The nurses experienced frustration with their diminishing physical strength, emotional vacuum, insufficient social status, and a lack of finances, which were obvious problems. Nurses often complained of physical problems, including; disabilities, bone problems, high blood pressure, and diabetes. The spouse of a retired nurse indicated that; “After two months, my husband went for a check-up. He was diagnosed with diabetes and hypertension, of which he knew nothing” (Participant's spouse 1).

Some of the retired nurses had mental and affective problems, and they experienced feelings of depression, despair, and sometimes regret. “Conditions brought about by working and the work environment make me angry” (Participant 16). The participants' experiences showed that a lack of respect towards deserving retired people was their most important social problem. “When you retire, people think that you can no longer do anything” (Participant 17).

Inability to pay living expenses was one of the most important problems affecting the nurses' adjustment process. In determining the basis of nurses' salary, 26 global criteria must be considered, but it wasn’t. “Salary paid to retired nurses is very low” (Participant 3). Identity threat was due to shock and disbelief, strict separation of work from personal life and frustration, could complicate a nurse's adjustment to retirement (24).

4.2. Negative Interaction

Participants stated that poor communication, less value given to experiences acquired during their life and being forgotten, all influenced the process of adaptation to retirement. Improper attitudes, disrespect, lack of gratitude, ignoring their experiences, were all upsetting for them and prevented them from adjusting to retirement.

4.2.1. Poor Communication

Improper attitudes of officials and its deterrent effects on adjustment to retirement were emphasized frequently by most of the retired nurses. “They are not respected in their job by their colleagues, and no attention is paid to them” (Participant 15).

4.2.2. Less Valued Acquired Experiences

Less value given to their acquired experiences had a deterrent role in adjustment to retirement. Failure to use their experiences and specialties caused the retired to avoid social participation. “No one wants our experiences. We are easily forgotten” (Participant 18).

4.2.3. Being Forgotten

Being forgotten depressed them more than before their retirement. “Three days after my retirement, the guard did not allow me to enter the hospital. He said that he did not know me” (Participant 11). Negative interactions exacerbate psychosocial stress, impairs self-esteem and induces feelings of worthlessness in retired nurses which delays retirement adjustment (25).

4.3. Identity Reconstruction

In the early stages, retired nurses were faced with a threat to their identity. They sought to balance their identity to confront the retirement’s stress. Participants trust in God, management of life problems, recognizing new opportunities, participation in charity activities, and reliving adjustment were factors affecting their adjustment to retirement. Reaching this stage for the nurses was very valuable, as it decreased the appearance of isolation and depression, enhanced their health and made life appear more normal. These strategies helped them to end their retirement crisis, and develop new adjustment skills. “Our nursing capabilities are enough” (Participant 13).

4.3.1. Trust in God

Religious beliefs, relying on the Almighty, imploring the Imams for help, recitation of the Koran, vows and oblations, and saying prayers, were all important factors that helped them adjust to retirement. “It was proved to me that worshiping God is only to serve the people” (Participant 10).

4.3.2. Management of Life Problems

Personal capabilities and problem-solving management facilitated the adjustment process. They were interested in participating in self-training programs and taking new measures and reeducations. “I feel that I am able to be fruitful” (Participant 9).

4.3.3. Recognizing New Opportunities

In order to recognize new opportunities, some of the participants tried to find a second job so that they could meet the needs of their families. “Fortunately, since we are experts, and society needs our skills and knowledge, anyone who wants, may work even after retirement” (Participant 5).

4.3.4. Participation in Charity Activities

Many retired nurses liked to participate in voluntary social activities and charity works to help the public. “The salary I was paid per month was equal to the salary my husband was paid for three days. I had no financial need, but I like to help patients” (Participant 12).

4.3.5. Reliving Adjustment

After many years, they could plan their days, and holiday activities in a more relaxed manner, and enjoy being with their families, friends and relatives. The retired nurses considered the new conditions in their lives, and changed their life style. “You work for 30 years, 7-8 hours a day. When you retire, your life is in your hands. It is a new birth” (Participant 7).

To the retired nurses, health was God's greatest blessing. Those nurses or their families who were in better health, had greater adjustment. “To improve health, you need to exercise, have suitable nutrition, good sleep, as well as read the Koran and be involved with religious activities” (Participant 10). Reconstructing their identity, and confronting the stress of retirement and its management were some of the challenges for retired nurses (26).

4.4. Supporting Factors

These consisted of subcategories such as support from family, friends, colleagues, and other retired nurses, society, authorities and organizations. Using supportive resources played an important role in coping with retirement and normalizing their lives.

4.4.1. Family

Satisfaction and intimacy with their family, especially their spouse made the retired nurses feel relaxed. “Thank God, my family is very good to me, particularly my husband. He is my best friend and this makes it easier for me to cope with retirement” (Participant 8).

4.4.2. Friends, Colleagues, and Other Retired Nurses

Engaging with friends and colleagues after retirement made the retired nurses feel proud and valuable. “Now I try to see my colleagues more often than I used to. Relationships have become more important than before” (Participant 14).

4.4.3. Society

Society has an important role to play in helping nurses to adjust to retirement. Nurses value being appreciated and respected by society for their 30-year service in improving society’s health. “Respecting the retired person must be more prevalent in society” (Participant 18).

4.4.4. Authorities

The retired nurses expected the authorities to be kind and appreciate them with gratitude for providing sincere and humanitarian services over the years and their friendly relationships with patients. “You like to have the authorities' appreciation and gratitude for the efforts you made over the years. I complained to the authorities about their lack of attention and support” (Participant 13).

4.4.5. Organizations

Organizations play an important role in supporting retired nurses in the roles they played in life, as well as in their transition to retirement. “After retirement, the university brought us to Mashhad for a three day pilgrimage. Good accommodation, food and reception at the beginning of our retirement were satisfactory” (Participant 15). Supportive factors can reduce the threat of identity with retirement and play an important role in helping nurses to cope with retirement and their return to normal life (26).

4.5. Normal Life

This consisted of subcategories, such as, feelings of comfort by the individual and feelings of comfort by the family. Retired nurses believe that retirement is necessary and invaluable. Not only for themselves, but also for their families to experience comfort and relaxation. “You can live for yourself, have a rest, and deal with yourself and your family” (Participant 5), one participant stated: “The most important thing for me is to take care of my family. Looking after my children is important” (Participant 18). Retired nurses adjusted to the changes the retirement brought to their lives and allocated more time for themselves and their families (25).

In Figure 1, a summary of themes, categories, and subcategories extracted from an analysis of the data is shown. Given the above descriptions, the main concern of the retired nurses was 'threat to identity'. They used strategies and supporting factors, such as identity reconstruction, to deal with threats to identity, adjust better to retirement, and return to normal life. The core variable was identity reconstruction as it was the basic social psychological process used to adjust to retirement.

4.6. Research Theory

The process of adjustment to retirement in nurses was influenced by issues that occurred during retirement (Figure 1). Nurses faced a number of identity threats after retirement, including; shock, frustration, disbelief, and a separation from work. The strategies they used to deal with this threat to identity included; trust in God, reorganizing their life, management of life issues, recognizing new opportunities, and participation in social activities. The nurses’ spouses supported them to adjust to retirement. Moreover, friends, colleagues and other retired nurses who had worked together for years communicated to each other either face to face or via telephone as they retired or were on the verge of retirement. Not valuing nurses’ acquired experiences by officials and authorities exacerbated their emotional irritability. They expected respect from society and organizations for their 30 years of experience and hard work, and more facilities after retirement. Nurses felt more comfortable after reconstruction of their identity and reintegration into working, which transferred easily to their families. The adjustment process was affected by the retired nurses' identity reconstruction (Table 1).

| Theme |

|---|

| Identity Threat |

| shock and disbelief |

| strict separation of work |

| frustration |

| Negative Interaction |

| poor communication |

| less value of the acquired experience |

| forgotten |

| Identity Reconstruction |

| trust in God |

| life management problems |

| recognizing new opportunities |

| participation in charity |

| reliving adjustment |

| Supporting Factors |

| support from family, friends, colleagues and other retired nurses |

| support from the society, authorities and organizations |

| Normal Life |

| feelings of comfort by the individual |

| feelings of comfort by the family |

Theme, Categories and Subcategories of the Adjustment Process in Retired Nurses

5. Discussion

The results from our study explained the categories of “Identity threat”, “Negative interaction”, “Identity reconstruction”, “Supporting factors”, and "Normal life", experienced by retired nurses in Semnan, Iran during their adjustment to retirement. Identity is an ongoing situation, which depends on the nature of human life experiences. Ericsson believes that a loss of work, from a psychological perspective, affects the personality and identity formation of retirees. Lack of preparation for their retirement was one of the most important problems faced by the nurses (27). Being unprepared for the mental and social changes encountered in retirement, lack of training courses, lack of familiarity with the regulations and codes of retirement, lack of attention to planning for leisure time, failure to plan for another suitable jobs, lack of financial resources, created challenges in the retirement adjustment process. Perkins believes that many individuals have no plan for retirement (28). Retirement can lead to decreased or loss of income, and affect a person's independence, social relationships and create increased leisure time (29). The results of previous studies have shown that individuals who had high levels of work creativity are not as active and adjusted during retirement as when they were working (30).

Health problems influence adjustment to retirement, and the nurses affected in this way were not satisfied with their retirement (depression, and irritation), while good health caused satisfaction with the retirement, and increased positive welfare during retirement (31). The majority of nurses complained of physical problems caused by the hard work associated with nursing. Disability, bone problems, hypertension, and diabetes were the most prevalent problems among the retired nurses. Retired individuals are one of the most vulnerable groups that develop various diseases (32). Chronic diseases are very prevalent among this group and they can lead to disability and death (33). Most chronic diseases are associated with an individual's working life (34). On the other hand, leaving work may increase their contact with health risks (35). Retirement is known to be an important stressful event (29). Loss of work is accompanied with depression, low self-confidence, and loss of identity (36, 37). Disrespect, cursing and assaults from those close to them and from people in society, all caused negative effects on them, and depleted their energy (38). The most frequent personal determinant reported in retirement, which increased the risk of depression, was dissatisfaction with life (39).

Dissatisfaction combined with low levels of attention and failure of respect suitable for their retired status were the causes of social problems encountered by the retired nurses. Many retired nurses are very attached to their work and this makes leaving it more difficult (40). During the retirement period, there is a lack of good organizational support to assist nurses adjust to the associated mental and social stressors (5).

One of the main problems nurses faced was low salary. Borg et al. suggested an association between low satisfaction with life and low economic status, which had social, health, and economic consequences (41). Valencia writes that money brings comfort with it. Nurses have to look after their families and want to remain independent (42). Many recent studies on retired people have shown that, due to the economic crisis, they have no savings or income (43). In addition to financial and health planning, psychological planning activities should also be promoted in order to facilitate a smooth adjustment to retirement (44). Deterrent factors decreased the nurses' attempts to adjust to retirement and live a normal life (45). Managers can increase their employees' capacity to adjust to retirement (46). Retired nurses considered the quality of social relations for their work experiences an effective factor for adjustment to retirement. (38). Atchley mentioned that adults value their last experiences by using continuation theory as an initial adjustment strategy to cope with changes throughout adulthood (47).

Reconstruction of identity is possible by obtaining significant activity against stress-induced retirement and adjustment. Most retired nurses wanted to use their capabilities to meet their needs and those of their families. Mental resources such as self-confidence also helped them during this adjustment period (48). Retirement can also have positive effects on self-confidence and feelings of self-control (49). The existence of higher levels of consciousness gained in the field of spirituality and religious beliefs in retired nurses also facilitated adjustment to their retirement. Personal spirituality may have an important role to play in facilitating their adjustment (43). They were more able to accept the status quo and start a new life. They can deal with their changed status and devote more time to their families (40). Planning and selection of fun activities had an important role in adjustment to retirement, and retired individuals who participated in leisure activities had greater satisfaction with their life (50). Work made them self-confident, and in the Crisis Theory of Rosow and Miller, work is the center of one's personal ability (36, 37). Employment during retirement is a sign of professional identity (51). When a retired individual is respected through their employment, they will have higher satisfaction with their work quality (52). As a result, many retired individuals who return to work, will have a higher level of social adjustment than other retired individuals (53).

Use of supporting resources had an important role in helping the nurses to cope with their retirement and return to normal life. Retirement needs to be supported to facilitate positive adjustment (54). Retired nurses tried to improve their current life conditions using support sources, such as their family and in particular their spouse, moreover, family relationships contributed to successful adjustment in retirement (31). The participants also felt satisfied, proud, and appreciated when they had supportive relationships with their colleagues. Retired nurses knew their colleagues as their friends and named them as supportive sources (55). Retired nurses also believed that social support reduced the stresses that accompany retirement. Support from the authorities was an important factor in the adjustment process. Supportive relationships can be a source of information and provide problem-solving skills, which improves their ability to return to effective performance (5). Organizations contribute in creating satisfaction with the roles played in life and subsequent adjustment to retirement (43).

By removing work responsibilities from retired nurses, they experienced feelings of comfort. Individuals who think that work includes difficulties, find that the loss of this role is often accompanied with increased positive interests and decreased signs of concern (56). After retirement, they wanted to increase their life satisfaction through being with their family members and meeting their needs. Many previous studies have shown that retirement leads to increased interactions with family and friends (55, 57-59). Andrews et al. defined three factors that influence this adaptation as; profession-related stress, inflexible work hours and salary (15). Individual access to key resources such as; finance, health, and family influenced coping ability in retirement (60). Religious practice and positive spirituality were related to personal growth, lower anxiety, and a reduction in depressive symptoms (61).

Grounded theory, knowledge that was already exist in relation to the retirement adjustment, was used to create a new theory titled "reconstruction of identity" for retired nurses. Retired nurses experience an identity threat after retirement (24). While the results of Wells and Kendig in Australia indicated that although retirees experience decreased levels of physical and social activities, they were happier and had higher self-efficacy and Sense of integrity, which were positive predictors of improvement in their health behaviors and welfare (62). Retired nurses felt frustrated following their retirement due to physical weakness, inadequate social support, emotional emptiness and desperate living situation (63). Moen writes that in American culture, the values of men and women are reduced after retirement and the skills and experience of those who have work hard are not compensated for by society (64). In addition, the results of Mayring's study in Germany showed that the transition to retirement was accompanied by increased leisure time (65). Retired nurses can experience physical weakness after retiring (63), while on the other hand, findings from a study by Mojon-Azzia in Switzerland indicated that retirement improves an individual's health, and reduces anxiety and depression (66). Osborne states that retirement can manifest as “cabin fever” for men and “empty nest syndrome” for women (27). While retired nurses received emotional support from their families (25). Some studies indicated that retired nurses were faced with a reduced standard of living (63, 67): however, the results of Kulik's study showed that the living conditions of retired people were not changed (57).

This study explored the retirement adjustment process according to the knowledge and experiences of retired Iranian nurses. By becoming aware of the factors affecting the adjustment process in retired nurses, effective steps can be taken to enhance nurses' adjustment to retirement and improve the health of this group. However, it is important to keep in mind that the results of qualitative studies cannot be generalized.