1. Context

Benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) is a common proliferative disease of the prostate in aging men. Benign prostate hyperplasia might develop since the age of 40 and is most prevalent among men who are in their 70 or 80s (1, 2). This condition causes subjective symptoms commonly known as lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), which consist of voiding and storage symptoms (3). This disease constituted 25% of urinary retention incidences from 2007 to 2010 in the United States (2).

Intravesical prostatic protrusion (IPP) is protrusion of the prostate into the bladder. The presence of IPP predicts more severe LUTS and urinary retention in patients with BPH (4). Intravesical prostatic protrusion is a failure predictor of trials without catheter (TWOCs) and medication (5). For men with BPH and IPP, surgical interventions such as open prostatectomy and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) have been considered superior to medical treatments in terms of LUTS relief (6). With surgery, the quality of life for patients with BPH, especially patients with IPP causing severe LUTS, will certainly increase. Evidence regarding IPP in BPH is mainly derived from cohort studies whose results differ from each other. Therefore, a systematic review would be a valuable addition to the understanding of the prognostic value of IPP.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Condition Description and Interventions

Studies were included if (1) the population was BPH patients who underwent prostatic removal through any methods available; (2) the severity of IPP was mentioned; and (3) the comparison of pre- and post-surgery IPSS was provided. In this systematic review, we assessed the prognostic value of IPP in terms of LUTS relief after surgery.

2.2. Database Search and Literature Screening

Literature search was performed in several online databases, including PubMed, ScienceDirect, EBSCO, and Cochrane Library, on 2 November 2020. The search strategy and keywords are shown in Table 1. The identified articles were analyzed for duplicates and screened for eligibility. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed during this study. The present systematic review was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD42020223793.

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed (MEDLINE) | ((((BPH[Title/Abstract]) OR (Benign prostatic hyperplasia[Title/Abstract])) OR (benign prostatic hyperplasia[MeSH Terms])) AND (((((((TURP[Title/Abstract]) OR (Transurethral Resection of the Prostate[Title/Abstract])) OR (TUIP[Title/Abstract])) OR (Transurethral incision of the prostate[Title/Abstract])) OR (Prostatectomy[Title/Abstract])) OR (Prostate surgical procedure[Title/Abstract])) OR (turp[MeSH Terms]))) AND ((IPP[Title/Abstract]) OR (Intravesical prostatic protrusion[Title/Abstract])) |

| Science Direct | (BPH OR Benign prostatic hyperplasia) AND (TURP OR Transurethral Resection of the Prostate OR TUIP OR Transurethral incision of the prostate OR Prostatectomy OR Prostate surgical procedure) AND (IPP OR Intravesical prostatic protrusion) |

| EBSCO | (BPH OR Benign prostatic hyperplasia) AND (TURP OR Transurethral Resection of the Prostate OR TUIP OR Transurethral incision of the prostate OR Prostatectomy OR Prostate surgical procedure) AND (IPP OR Intravesical prostatic protrusion) |

| Cochrane | (BPH[Title/Abstract]) OR (Benign prostatic hyperplasia[Title/Abstract]) AND (((((((TURP[Title/Abstract]) OR (Transurethral Resection of the Prostate[Title/Abstract])) OR (TUIP[Title/Abstract])) OR (Transurethral incision of the prostate[Title/Abstract])) OR (Prostatectomy[Title/Abstract])) OR (Prostate surgical procedure[Title/Abstract])) AND ((IPP[Title/Abstract]) OR (Intravesical prostatic protrusion[Title/Abstract])) |

Online Databases and Keywords Used in This Study

2.3. Study Selection

Studies that fulfilled our criteria were assessed for their characteristics, such as subject types and results. Each study was independently assessed by BG and HE, using predetermined eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria in this study were: (1) patient population with BPH who had undergone surgery; (2) English/Indonesian-language articles; (3) randomized controlled trial (RCT), cohort, or case-control studies.

We included all types of prostate surgical techniques for BPH. The exclusion criteria included review articles, case reports, case series, editorial letters, studies on animals, and/or studies with unavailable full-text. The search was conducted simultaneously by both assessors using the aforementioned keywords and search strategy. Studies were then screened independently based on their titles and abstracts. Full-text of studies with relevant titles and abstracts were assessed by both authors. Should any disagreements existed, both authors would thoroughly discuss them until a consensus was reached.

2.4. Data Extraction and Outcome of Interest

Data extraction was conducted by both authors, and a consensus was achieved regarding any initial disagreement. The number of samples, country, age, study design, prostate volume, type of surgery, IPP stratification, IPP measurement method, follow-up duration, outcome measurement, and result were extracted (Table 2). Pre- and post-surgery IPSS were regarded as the primary outcome. Secondary outcome measurements included Qmax and post-voiding residue (PVR).

| Study | Samples (N) | Country | Age (y) | Study Design | Prostate Volume (mL) | Surgery Type | IPP Stratification | IPP Measurement Method | Follow up Duration | Outcome Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. 2011 (7) | 239 | Shanghai, China | 65.5 ± 8.1 | Prospective | 75.0 ± 38.5 | TURP | Cntinue | TRUS | 6 months post-surgery | Effective and not effective (IPSS, QoL, and Qmax) |

| Lee et al. 2012 (5) | 177 | Korea | 70.3 ± 6.9 | Retrospective | 57.0 ± 32.7 | TURP | < 5 mm; ≥ 5 mm | TRUS | 3 months post-surgery | IPSS, IPSS-v, IPSS-s; PVR; Qmax |

| Wee et al. 2012(4) | 389 | Korea | 72 | Prospective | Group I: 44.79 ± 20.78; Group II: 58.01 ± 20.08; Group III: 58.01 ± 20.08 | PVP | < 5 mm; 5 - 10 mm; > 10 mm | TRUS | 1 - 12 months post-surgery | IPSS, IPSS-v, IPSS-s; PVR; Qmax |

| Kim et al. 2013 (8) | 134 | Korea | 66.6 ± 7.8 | Prospective | 42.9 ± 16.7 | PVP | IPP and no IPP | TRUS | 1 - 6 months post-surgery | IPSS, IPSS-v, IPSS-s |

| Li et al. 2019 (9) | 257 | Fujian, China | n/a | Prospective | ≤ 30 | TURP or PKEP | continue | TRUS | 3 - 12 months post-surgery | IPSS, IPSS-v, IPSS-s |

| Shim et al. 2019 (10) | 488 | Gyeonggi-do, Korea | 67.3 ± 11.2 | Retrospective | 54.6 ± 27.9 | TURP | continue | TRUS | 3 months before - 3 months post-surgery | IPSS, IPSS-s, IPSS-v, Qmax; PVR |

| Chen et al. 2020 (11) | 96 | Nanjing, China | 72.72 ± 7.94 | Retrospective | n/a | HoLEP | continue | TAUS | 3 months post-surgery | Success (IPSS < 7 or IPSS score improve > 50%); Failure |

Characteristic of the Study Included in This Systematic Review

2.5. Assessment of Methodologic Quality

After the literature search and selection processes were done, the chosen articles were critically appraised. The critical appraisal method used was the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for nonrandomized studies. Several aspects of the reviewed studies were included, such as PICO components, PICO measurements, study designs, number of samples, follow-up durations, blinding methods, and outcome measurements, such as numerical values, the proportion of cases, and controls, P-values, and odds ratios (ORs).

2.6. Bias Assessment

Bias assessment was conducted by evaluating selection bias, comparability bias, and outcome bias. Each bias checklist was given a 0 - 2 score, according to the NOS manual, with a total score of 10. No NOS score grading has been universally established. However, in our study, we defined a NOS score > 7 as a high-quality study.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

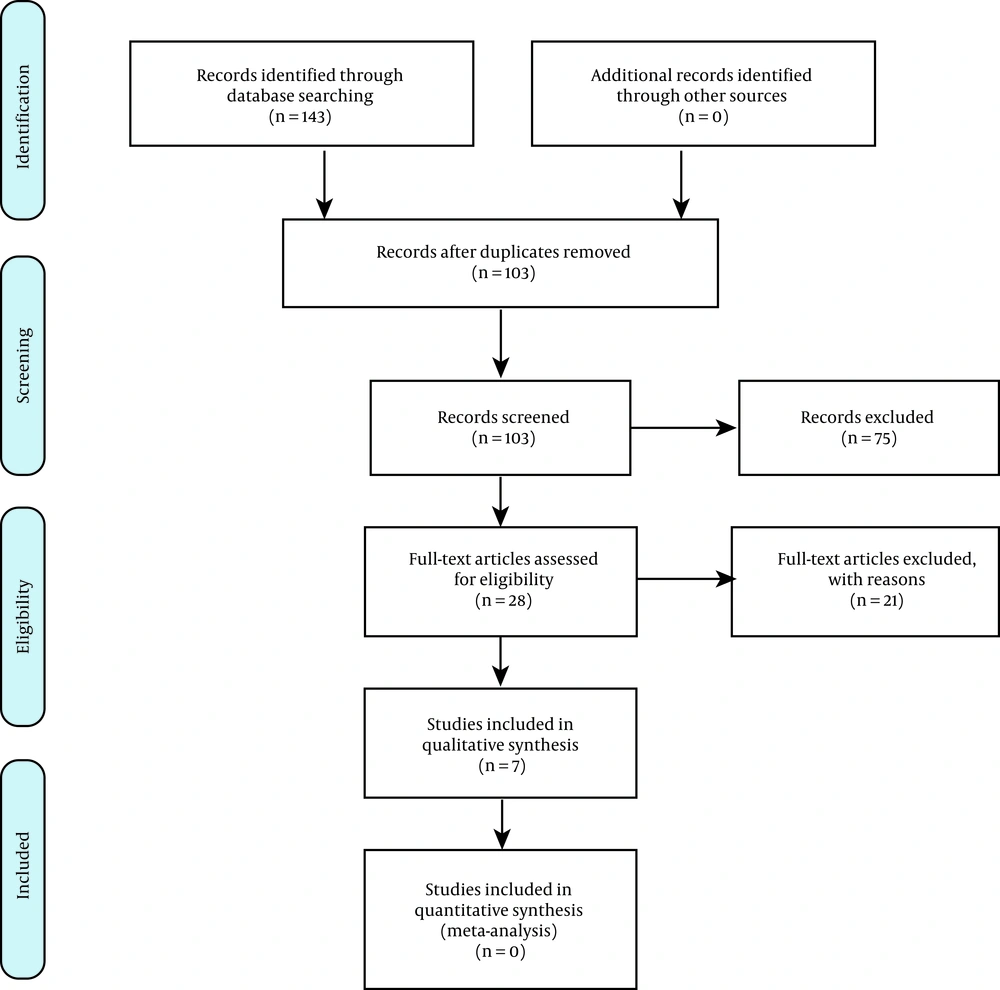

The initial database search yielded 143 papers. Of these, 115 papers were excluded during abstract screening, and seven papers were considered for full-text analysis. All seven papers were included in our systematic review. The details of the electronic search are presented in Figure 1.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 2.

3.3. Quality Assessment and Bias Assessment

First, critical appraisal was performed to identify the individual quality of the obtained studies. Our critical appraisal of observational studies was based on the NOS. The details of our critical appraisal are shown in Table 3. All the studies demonstrated high quality scores, defined as a NOS total score of > 7. Some studies involved a comparability bias due to a lack of adjustment for other risk factors using multivariate analysis. Some studies demonstrated an outcome bias due to a lack of follow-up. A lack of follow-up issue is defined in the NOS as > 20% of participants leaving a study or a study failing to include complete information about follow-ups.

| Study | Selection Bias | Comparability | Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of Exposed Cohort | Selection of Non-exposed Cohort | Ascertainment of Exposure | Demonstration That Outcome of Interest Was Not Present at Start of Study | Adjust for the Most Important Risk Factors | Adjust for Other Risk Factors | Assessment of Outcome | Follow-Up Length | Loss to Follow-Up | Total Quality Score | |

| Huang et al. 2011 (7) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 10 |

| Lee et al. 2012 (5) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 10 |

| Wee et al. 2012 (4) | * | * | * | * | * | - | * | * | - | 8 |

| Kim et al. 2013 (8) | * | * | * | * | * | - | * | * | - | 8 |

| Li et al. 2019 (9) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | - | 9 |

| Shim et al. 2019 (10) | * | * | * | * | * | - | * | * | - | 8 |

| Chen et al. 2020 (11) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 10 |

Quality Assessment of the Included Studies Using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

3.4. Surgical Procedure

We identified varieties of surgical procedures within the reviewed studies. Three of the studies implemented TURP as their surgical procedure. Two studies used greenlight HPS laser photoselective vaporization (PVP). One study implemented TURP or transurethral plasmakinetic enucleation of the prostate (PKEP), and one study used Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP).

3.5. Intravesical Protrusion Measurement

Most studies measured IPP using transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) in millimeters. Only one study used TAUS to measure IPP. Categorization was very diverse, with some studies using numerical variables in millimeters for IPP while others categorized IPP as < 5 mm, 5 - 10 mm, and > 10 mm.

3.6. Postoperative IPSS, IPSS-v, IPSS-S, and Qmax

International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) measurements included IPSS, IPSS-S, and IPSS-V. Changes in IPSS were measured one, three, six, and 12 months postoperatively. In the first postoperative month, two studies showed significant IPSS differences and better outcomes in patients with IPP versus in those without IPP (1). One study showed no significant differences between IPP and IPSS postoperatively (2). Four studies showed significantly better IPSS outcomes three months postoperatively in patients with higher IPP measurements, and two studies showed no significant differences. A study by Lee et al. (5) showed adjusted OR of 3.43 for IPSS improvement in favor of patients with significant IPP (≥ 5 mm). Three studies showed no significant IPSS differences between IPP groups at six months after surgery. A study by Li et al. (9) showed that the higher preoperative-IPP group had better odds of IPSS improvement (OR 1.61; 95% CI) at 12-month of follow-up. The same study also demonstrated a significantly better outcome in patients with higher preoperative-IPP at three- and 12-month follow-ups. Kim et al. (8) found that the higher preoperative-IPP group had better IPSS at one- and three-month follow-up, yet there was no significant difference at six-month follow-up.

4. Discussion

Intravesical prostatic protrusion occurs in BPH due to an overgrowth of the median prostatic lobe into the bladder. Intravesical prostatic protrusion is calculated based on the shortest length of the prostate protrusion tip to the base of the bladder by the sagittal plane, which reflects the maximum longitudinal length of the prostate. Intravesical prostatic protrusion correlates with bladder outlet symptoms (BOO). Protrusion of the median lobe into the bladder causes a “ball-valve” type obstruction, causing dyskinesia upon bladder movement.

As opposed to a compression of the urethra due to lateral lobe hypertrophy, which can be forced open by a tight contraction of the bladder, a protrusion due to median lobe hypertrophy is more difficult to control, even with adequate bladder contraction (12). This obstruction causes intravesical pressure response, increasing the threshold of detrusor muscle contraction to induce micturition. Intravesical prostatic protrusion increases the risk of prostate deformation due to high intravesical pressure. The pathophysiology underlying this deformation is the fascial fusion in the superior part of the prostate. The prostate is covered by the adhesion of fascial “capsule” anteriorly to the puboprostatic ligament, posteriorly to the Denonvilliers’ fascia, and laterally to the endopelvic fascia. As these supportive fascia and structure disintegrate, they fuse with other fasciae, and therefore, cause the superior prostate protrusion more susceptible to a radial pressure. Radial pressure can cause prostate deformity and compression in the pars prostatic urethra (13). This pathophysiology underlies IPP as an independent factor of IPSS severity and a risk factor for terminal dribbling (12). Storage symptoms can also increase due to the thickening of the bladder wall. The bladder overactivation caused by constant obstruction can lead to bladder wall hypertrophy. This muscle hypertrophy may present with hypersensitive afferent innervation, thereby activating unmyelinated C fibers, a feature which is generally absent from normal bladder (4).

Several studies have shown that patients with IPP tend to fare better post-operatively. However, several studies have shown no significant differences between the two groups. Studies by Wee et al. (4) and Shim et al. (10) showed no significant effect of IPP on post-surgery outcomes. Studies by Huang et al. (7), Lee et al. (5), Kim et al. (8), Li et al. (9), and Chen et al. (11) showed a significant correlation between IPP and post-surgery LUTS relief. The sustainability of these differences between groups is also controversial. The study by Kim et al. (8) showed that IPP is a predictor of better IPSS at one month and three months post-surgery. However, no significant difference was found at six months post-surgery. In contrast, Li et al. (9) showed IPP’s significance as a predictor of LUTS improvement for up to 12 months post-surgery. One theory that could explain this phenomenon is that BPH patients with IPP generally have symptoms that are more prominent in obstruction caused by a ball or spherical valve obstruction.

Prostate surgery provides early symptom improvement because it successfully removes the obstruction. Therefore, patients with IPP have a more prominent early symptoms improvement than those without IPP. This theory was confirmed by a study by Chia et al. (14), in which IPP was shown to relate closer to voiding symptoms than to storage symptoms. In addition to the voiding effect, IPP can also cause storage symptoms, which may explain the significant post-surgery improvement.

A study by Lee et al. (15) showed an association between IPP and the storage symptoms caused by bladder-neck and trigone irritation. In addition, Fowler et al. (16) showed that IPP can cause a less-than-optimal closing of the bladder neck, resulting in the passage of urine to the prostatic urethrae and causing a micturition reflex. Surgical procedures can resolve existing prostate deformities so that irritation and a micturition reflex due to incontinence can resolve quickly, increasing patient’s symptom improvement. Another possible theory for symptom improvement in IPP patients is the bias of the surgeon in evaluating postoperative IPSS due to the apparent improvement of the symptoms. However, this theory can be refuted because upon urodynamic examination, patients with IPP also had better urodynamic improvements (Qmax or PVR) than patients without IPP.

The authors could not control several factors in this systematic review. First, information regarding the TRUS operator was not clearly shown in all studies. TRUS is a noninvasive radiological instrument that is operator-dependent, which is why its results are largely determined by the operator’s experience. In addition, this study involved various inhomogeneous surgical techniques, which may have caused post-surgery LUTS to differ, depending on the technique used. However, all the surgical techniques used showed effectiveness for patients with and without IPP. Information regarding the duration of a patient’s illness before they undergo surgery is also vital. This information relates to the pathophysiology of chronic BOO, namely, detrusor overactivity and a thickening of the bladder wall, which results in bladder failure and provides a poor post-surgery prognosis.

4.1. Conclusions

Most studies suggest that IPP predicts better post-surgery LUTS improvement. Further studies which take into account the risk of bias in TRUS use, surgical techniques, and the duration of patients’ illness before they receive surgical management are needed.