1. Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is an infectious disease affecting approximately 71 million people worldwide (1, 2). Chronic HCV infection leads to chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, and in some cases, it can lead to hepatic decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (3). While kidney disease can be an extrahepatic manifestation of HCV infection, HCV can also be transmitted in patients with renal disease through hemodialysis (4). Chronic HCV infection is prevalent in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, and it can increase the morbidity and mortality rate of hemodialysis and kidney transplant patients (5). Furthermore, HCV infection accelerates renal deterioration by glomerulonephritis or cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (6). Consequently, the elimination of HCV infection can reduce mortality by ameliorating complications in patients on chronic hemodialysis (2, 5, 7-9).

Until recent years, the treatment of HCV infection was based on interferon-based therapies, which started even before the identification of HCV in 1989 (10). The significant development in the understanding of molecular virology, pathogenesis, and the structure of HCV affected the clinical treatments of HCV infection, which commenced the practice of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) (11). Since sofosbuvir (SOF), as the main component of HCV antiviral treatment, is not recommended in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, the treatment of HCV among patients on hemodialysis is challenging in terms of the limited number of approved regimens (12-14).

SOF, a nucleotide analog, and HCV RNA polymerase (NS5B) inhibitor is a common treatment for HCV infection. Turning to patients with renal impairments, SOF is only approved for patients with an eGFR > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, since the major metabolite of SOF (GS-331007) is significantly higher in these patients. Many studies suggested the favorable outcome of utilizing SOF in patients with renal complications. For example, Dumortier et al. (15) strongly suggested that SOF treatment with the dose reduction is safe and efficient in patients with end-stage renal disease and those undergoing hemodialysis. Daclatasvir (DCV) is an inhibitor of the HCV NS5A replication complex that stops HCV viral RNA transcription and protein translation. A study by Garimella et al. (16) demonstrated the single-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of DCV in subjects with renal function impairment. The combination of SOF/DCV is used for HCV infection, and both were recommended by previous studies for patients with renal impairments (11, 17, 18). However, it is not recommended to use SOF in CKD with eGFR < 30. There are regimens without SOF, such as grazoprevir/elbasvir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, which are used for CKD with eGFR < 30; but these regimens are not available in Iran as brand name or generics. Therefore, we attempted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the SOF/DCV for the treatment of hemodialysis patients with HCV infection.

2. Methods

The current retrospective study was conducted at the Middle East Liver Disease (MELD) Center, Tehran, Iran, from 2017 to 2019. The participants included 51 individuals aged > 18 years old, who were on hemodialysis due to renal impairment with eGFR < 30, and suffering from HCV infection in the chronic phase (positive for HCV RNA for over six months). Subjects with HCC, Child-Pugh score > 12, low heart rate (< 50/min), under medication of amiodarone for the past six months, or have a history of failure to NS5A inhibitor-containing regimen, and also patients with HIV or HBV coinfections were excluded from the study. All patients were subjected to constant dose SOF 400 mg/DCV 60 mg (Sodakvir®; Bakhtar Bioshimi, Kermanshah, Iran or Datex®; Sobhan Medicine Trade Development Co, Tehran, Iran) for 12 weeks in patients without cirrhosis, and 24 weeks in patients with cirrhosis. We evaluated the treatment efficacy utilizing the PCR assay (COBAS TaqMan, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) 12 weeks after treatment termination, and undetectable HCV RNA was regarded as a sustained virologic response (SVR). Treatment safety was assessed in terms of severe adverse events reported by the study participants.

This study was performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki with the ethical code of IR.BMSU.BAQ.REC.1398.017. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (BUMS), Tehran, Iran. Due to the retrospective design of the study, we did not get written informed consent from the participants. The statistical analysis was conducted utilizing SPSS version 22.0 software.

3. Results

A total of 51 hemodialysis patients with HCV infection were recruited in this study, 31.4% of whom had cirrhosis. Moreover, 35 (68.6%) patients were males, and the mean age of subjects was 57.6 years old. The majority (84.3%) of patients did not have any history of HCV antiviral therapy (Table 1).

| Characteristics | All Patients (N = 51) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 57.6 ± 12.0 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 35 (68.6) |

| Female | 16 (31.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 ± 4.2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.7 ± 2.0 |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 179.6 ± 77.5 |

| AST (IU/L) | 29.7 ± 27.2 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 33.8 ± 55.3 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 8.6 ± 7.5 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.4 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| Liver disease status | |

| Without cirrhosis | 35 (68.6) |

| With cirrhosis | 16 (31.4) |

| HCV genotype | |

| 1 | 26 (51.0) |

| 2 | 2 (3.9) |

| 3 | 9 (17.6) |

| 4 | 3 (5.9) |

| Unknown | 11 (21.6) |

| Treatment history | |

| Treatment naïve | 43 (84.3) |

| Interferon-experienced | 8 (15.7) |

| DAA-experienced | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; DAA, direct-acting antiviral agent; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD and No. (%).

All 35 (68.6%) patients who indicated no cirrhosis signs were subjected to a constant dose of SOF/DCV for 12 weeks and 16 (31.4%) patients with cirrhosis were treated for 24 weeks.

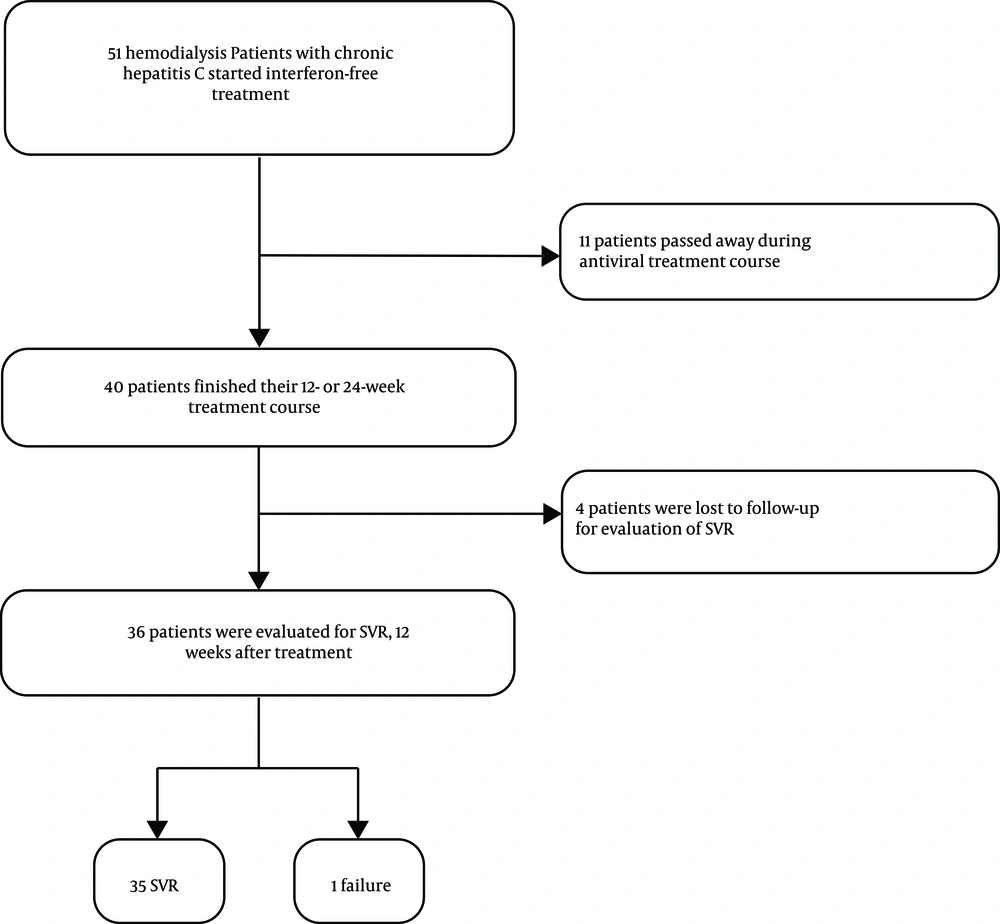

Eleven patients were excluded during the treatment due to reasons not related to the liver diseases or antiviral therapy, and four subjects were lost to follow-up for evaluation of SVR (Figure 1). Among 36 subjects who completed the treatment and were available for the evaluation of SVR, 35 (97.2%, 95% CI: 85.5 - 99.9%) patients achieved SVR and only one (2.8%, 95% CI: 0.1 - 14.5%) patient relapsed. The patient with treatment failure was a 59-year-old patient with cirrhosis and without any history of treatment. None of the patients reported severe adverse events in the appointments nor discontinued treatment as a result of the treatment-related adverse events.

4. Discussion

This study attempted to investigate the safety and efficacy of SOF/DCV combination therapy in Iranian hemodialysis patients with chronic HCV infection. Several studies have shown that HCV infection in hemodialysis patients increases morbidity and mortality rates. A study by Kalantar-Zadeh et al. (19) in the US, including 13,000 hemodialysis patients, demonstrated that HCV infection increased the mortality rate in hemodialysis patients. The prevalence of HCV infection in hemodialysis patients was reported as 13.5% in America, Europe, and Asia (20). It has been shown that the treatment of patients on hemodialysis with chronic HCV infection is challenging. Before the first-generation DAAs (telaprevir and boceprevir), the gold standard of care for HCV infection was pegylated interferon (peg-IFN) plus ribavirin. However, ribavirin is not tolerated in patients with renal impairment since it is eliminated mainly by the kidney and it cannot be removed by hemodialysis, and utilizing peg-IFN alone is accompanied with low response rate, therein lies the problem for the treatment of HCV infection in hemodialysis patients (5). Consequently, the introduction of DAA-based IFN- and RBV-free regimens changed the HCV management scenario in hemodialysis patients. However, low doses of SOF (200 mg daily or 400 mg three times a week) are suggested in patients with renal impairment because the predominant metabolite of SOF (GS-331007) is excreted by the kidney, and in patients with renal impairment, the plasma level of GS-331007 increased up to 20 times. It should be noted that hemodialysis removes this metabolite from the plasma by 53%, even though there is no evidence for the adverse effect of GS metabolite of SOF (21, 22).

Poustchi et al. (23) pointed out that even though there was no pharmacokinetic data indicating plasma level of SOF, administration of SOF/DCV in Iranian hemodialysis patients with HCV infection and renal impairment was proved to be safe without observation of any serious adverse event, which is in line with our results. A meta-analysis (24) showed that SOF-based regimens are effective, with a 97% SVR12 rate, in patients with advanced CKD. In this meta-analysis, the efficacy of SOF/DCV in patients with advanced CKD was 97%, which is consistent with the results of the current study (24). Dual administration of DCV and SOF daily demonstrated a noticeable effect in the course of 12-week treatment in HCV patients. The safety and tolerance of this treatment have been approved to be sufficient (25). Interestingly, DCV is mainly eliminated through the liver by cytochrome p450, thereby making it a great candidate for the combinational therapy of HCV patients with renal impairments (26).

The main limitations of this study included single-center case recruitment, small sample size, and retrospective data collection, which limited the results in terms of patient follow-up and collecting the treatment adherence and side effects data.

This study showed that not only a combination of SOF/DCV is safe for the treatment of hemodialysis patients with HCV infection, but also it can affect the clinical management of HCV infection according to excellent efficacy of treatment in patients with severe renal impairment (97.2% of patients achieved SVR). The SOF/DCV regimen can help eliminate the HCV infection in patients with advanced CKD in Iran and other countries where the approved regimens for these patients are unavailable.