1. Introduction

The suprapubic catheter (SPC) and bladder indwelling catheter (BIC) are useful devices widely used in urological patients, and their iterative replacement is necessary for patients with pharmacologically intractable bladder emptying disorder. Urinary catheterization is associated with complications over the short (trauma, urosepsis, acute kidney injury (AKI)) and long term (urethral stricture), leading to a greater cost burden on medical departments (1-3). Unintentional intraureteral misplacement of SPCs and BICs is infrequent, with potentially life-threatening complications, such as ureteral trauma. Although it has been described mostly in patients with neurogenic bladder, its mechanism remains unclear. This paper aims to describe two rare cases of unintentional ureteral obstruction after routine replacement of an SPC and BIC that occurred in our institution, review the literature, explain possible factors favoring this occurrence and suggest measures to manage and prevent it.

2. Case Presentation

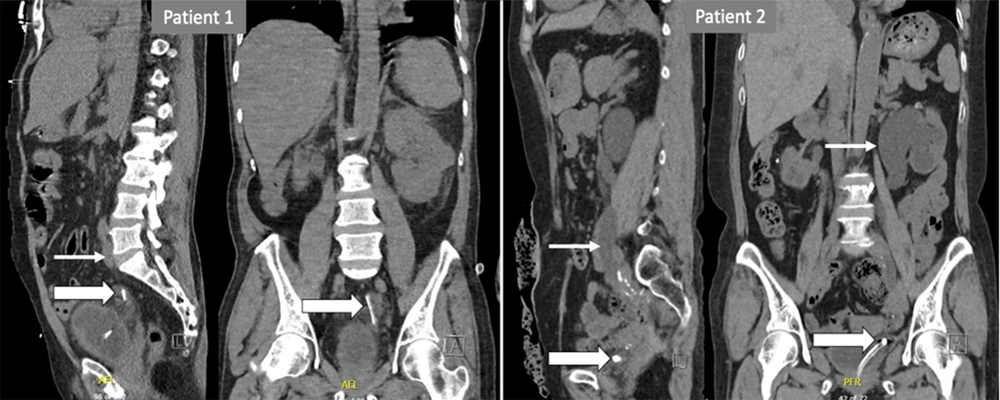

Patient 1: 66-year-old man with medical and surgical antecedents of chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3b of multifactorial origin, right renal atrophy, transurethral resection of the prostate, multi-operated bulbar urethral stricture, recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI), and carrier of an SPC with iterative changes. Six hours after the last 12Fr siliconized SPC replacement, he attended the emergency room (ER) with deterioration of the general condition, lumbar pain, anuria, and fever of 39°C. He was tachycardic (heart rate of 120 beats/min), with no hypotension or respiratory alterations (detailed laboratory findings in Table 1). Blood tests showed an elevated leukocyte count of 21.34 × 103 cells/µL, elevated c-reactive protein (CRP) of 194.9 mg/L, GFR according to CKD-EPI was 4 mL/min/1.73 m2, with creatinine of 13.7 mg/dL, and urea of 294 mg/dL, hyperkalemia of 6.6 mmol/L; metabolic acidosis. Urine culture was positive for E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Figure 1). CT scan revealed a left uretero-hydronephrosis secondary to obstruction by the inflated SPC balloon in the distal ureter 4 cm from the vesicoureteral junction (VUJ). He was admitted for urosepsis and AKI. The catheter's balloon was deflated, and the catheter was carefully removed and repositioned into the bladder with 5 mL of sterile water in the balloon; the correct position was confirmed with ultrasound; he was hospitalized, and antibiotic treatment was started. Decreased hydronephrosis was confirmed three days later with renal ultrasound. The patient was discharged on the fifth day of hospitalization with clinical and analytical improvement.

| Variables | Reference Ranges | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Values | Admission | Discharge | Baseline Values | Admission | Discharge | ||

| GFR CKD-EPI | > 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 18 | 4 | 19 | 12 | 6.9 | 8 |

| Creatinine | 0.7 - 1.3 mg/dL | 3.23 | 13.7 | 3.28 | 3.76 | 6.13 | 5.28 |

| Leucocyte | 3.5 - 11.00 × 103 cells/µL | 21.34 | 4.74 | 8.27 | 7.43 | ||

| CRP | < 10 mg/L | 194.9 | 3.6 | 89.9 | 6.3 | ||

| Urea | 17 - 48 mg/dL | 48 | 294 | 53 | 92 | 134 | 123 |

| Potassium | 3.4 - 4.5 mmol/L | 6.6 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 4.1 | ||

| Bicarbonate | 22 - 28 mmol/L | 10 | 20 | 18 | 18 | ||

| pH | 7.35 - 7.45 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.39 | ||

| Lactate | < 2 mmol/L | 3.5 | 2 | ||||

Patient 1: Large arrows indicate the suprapubic catheter into the left distal ureter up to 4 cm from the VUJ; a small arrow indicates the left hydroureter. Patient 2: Large arrows indicate the bladder catheter within the intramural tract of the left distal ureter. Small arrows indicate left hydronephrosis.

Patient 2: 59-year-old woman with medical and surgical antecedents of CKD stage 3b of multifactorial origin, low anterior resection, and radio-chemotherapy for rectal adenocarcinoma, bowel perforation, permanent discharge colostomy, micro-bladder (maximum capacity 50 cc), severe urinary incontinence, recurrent UTI and permanent 16Fr siliconized BIC. She attended the ER 24 hours after the last BIC replacement for hypogastric pain radiating to the left lumbar fossa, nausea, hematuria, oliguria, and peri-catheter urine leakage. Normal vital parameters. Blood tests showed a normal amount of leukocytes, CRP 89.8 mg/L, creatinine 6.13 mg/dL, CKD-EPI 6.9 mL/min/1.73 m2, and hyperkalemia 4.9 mmol/L. Urine culture was positive for P. aeruginosa (Figure 1). CT scan revealed a left uretero-hydronephrosis secondary to obstruction by the inflated SPC balloon in the intramural tract of the ipsilateral ureter. The balloon was deflated, and the catheter was carefully removed and replaced; the intravesical position was confirmed by ultrasound. She was admitted for AKI and UTI. Decreased hydronephrosis was confirmed three days later with renal ultrasound, renal function improved, hematuria was self-limited, and she was discharged with oral antibiotics.

3. Discussion

The most frequent injuries associated with BIC are urethral trauma and retention of the catheter's balloon within the urethra (4); placement of an SPC is technically more complex with a risk of abdominal organ injury and mortality risk of up to 2,4% (5). Other complications include hematuria, spasms, stone formation, obstructions, catheter leakage, and a tendency to dislocate, especially in cognitively impaired persons (1).

Inadvertent placement of BIC and SPC within the ureter is a rare event, with only 27 and 8 cases reported respectively so far, of which 12 right and 15 left for BIC and three right and 5 left for SPC (Table 2). There is no significant difference in terms of laterality, inadvertent placement of BIC has a female predominance of 3.5:1, while in the case of PCS it is more frequent in men at 7:1. Of the 35 patients reported, 28 (80%) underwent iterative catheter changes, mostly due to neurogenic bladder (17 cases). Although in less than half of the cases (6), there were no reported consequences, the most frequent ones were pyelonephritis (8 cases) and ureteral rupture (6 cases).

| Author | Gendre | Linked Condition | Catheter | Side | Clinical Presentation | Clinical Debut | Consequence | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borrero et al. (7) | Male | NB | SPC | Left | Fever, pain | NC | CC | |

| Singh and Eardley (8) | Female | NB | BIC | Right | ||||

| Kato (9) | Female | SIn, bilateral VUR | IDC | Left | No urine came out during aspiration | Immediate | CC | |

| Ogan and Berger (10) | Female | BIC | Right | Pain | UR | SR | ||

| Muneer et al. (11) | Male | Fibrotic bladder | BIC | Right | Pain | NC | Endo. incision | |

| Hara et al. (12) | Female | During laparotomy | BIC | Left | Pain | 4 h | NC | DJ |

| George and Tharion (13) | Male | NB | BIC | Right | Pain, leakage around the catheter | 1 d | NC | CC |

| Maegele et al. (14) | Female | BIC | Left | Pain, fever, vomit | Pyelonephritis | CC | ||

| Kim and Park (15) | Female | NB | BIC | Right | Pain | UR | PCN (DJ failed) | |

| Dangle et al. (16) | Female | After pyeloplasty | SPC | Left | Pain, oliguria | 14 | Pyelonephritis | CC |

| Papacharalabous et al. (17) | Female | During laparotomy | BIC | Left | Intraoperative | UR | SR | |

| Hale et al. (18) | Female | BIC | Left | Pain | UR | SR | ||

| Adeyemo et al. (19) | Male | NB | SPC | Right | Pain, oliguria | 60 | Pyelonephritis | CC |

| Baker et al. (20) | Female | NB | BIC | Left | Oliguria | Few hours | UR | PCN |

| Anderson and Greenlund (21) | Female | NB | BIC | Right | Pain, haematuria | 1 d | AR | CC |

| Anderson and Greenlund (21) | Man | NB | BIC | Left | Pain, haematuria | 1 d | NC | CC |

| Ishikawa et al. (22) | Female | NB | BIC | Left | Leakage around the catheter, pain | 2 d | NC | CC |

| Ishikawa et al. (22) | Female | NB | BIC | Left | Fever | 18 d | Pyelonephritis | CC |

| Ishikawa et al. (22) | Male | NB | BIC | Left | Fever | 3 d | Pyelonephritis | CC |

| Viswanatha et al. (23) | Female | Duplex ureter | BIC | Right | Pain, unable to deflate the balloon | During cesarean | NC | URS |

| Modi et al. (24) | Female | NB | BIC | Right | UR | PCN (DJ failed) | ||

| Crawford et al. (25) | Female | Interstitial cistitis | BIC | Right | Pain, unable to remove the catheter | Same day | NC | PTCB, DJ |

| Yune et al. (26) | Female | Ectopic uréter | BIC | Left | Oliguria post-cesarean section | |||

| Luo et al. (27) | Male | NB | BIC | Right | Fever, Pain | 2 d | Pyelonephritis | CC |

| Luo et al. (27) | Female | Post radiotherapy | BIC | Right | NC | CC | ||

| Luo et al. (27) | Female | UR, psychiatric drugs | BIC | Left | NC | CC | ||

| Agarwal et al. (28) | Male | NB | SPC | Left | Haematuria, pain, fever, incontinence | 12 | Pyelonephritis | CC |

| Persaud et al. (29) | Male | Urethral stricture | SPC | Right | Flank pain | 30 | NC | CR |

| Agarwal et al. (28) | Female | NB | BIC | Left | Haematuria, pain, unable to deflate the balloon | 1 d | NC | PPCB |

| Locherbach et al. (30) | Female | Nephrolithiasis | BIC | Left | During URS | NC | CR | |

| Cho et al. (6) | Male | No antecedents | BIC | Right | Oliguria, unable to remove the catheter | Immediate | NC | CC |

| Mekayten and Duvdevani (31) | Male | NB | SPC | Left | Nausea, pain, oliguria | 10 | NC | CC |

| Saad and Zhong (32) | Male | NB | SPC | Right | Pain, haematuria | 2 | NC | CR |

| VC et al. (2022) | Male | Urethral stricture | SPC | Left | Pain, fever, anuria | 1 | Pyelonephritis | CR |

| VC et al. (2022) | Female | Post radiotherapy | BIC | Left | Pain, nausea, haematuria, oliguria | 1 d | Lower UTI | CC |

Abbreviations: NB, neurogenic bladder; SIn, severe incontinence; VUR, vesico-ureteral reflux; BIC, bladder indwelling catheter; SPC, suprapubic catheter; VUR, vesico-ureteral reflux; NC, no consequence; UR, ureteric rupture; AR, autonomic response; UTI, urinary tract infection; CC, catheter changement; SR, surgical repair; DJ stent, double j stent; PCN, percutaneous nephrostomy; URS, ureteroscopy; PTCB, punction through the catheter balloon; CR, catheter repositioning; PPCB, percutaneous puncture of the catheter balloon.

Long-term urinary catheter users often have multiple medical, surgical, and even radiotherapeutic background, following damage to the detrusor muscle's structure, and consequent bladder alteration emptying, recurrent UTI, and high prevalence of renal scarring, caliectasis, and CKD (33). These antecedents associated with the permanent presence of a catheter increase the risk of suffering urosepsis (34).

Possible reasons for inadvertent ureteral catheterization have been described (22, 27, 30):

- In patients with long-term catheterization, the bladder tends to contract and decrease its capacity (alteration of the anatomical relationship between the bladder neck and ureteral orifices).

- Each change of catheter increases the chances of ectopic catheterization, especially if the bladder is empty.

- In patients with neurogenic bladder, there may be ureteral reflux with patulous ureteral orifices, which may facilitate catheter entry into the ureteral meatus.

In addition, in women, the absence of the median prostatic lobe could justify the higher proportion of patients with BIC misplacement than in men; this is deduced by the almost absence of reported cases of SPC misplacement in women. These conditions may explain the intraureteral entry of BIC or SPC during their placement or the spontaneous intraureteral migration of the catheter, which can occur on more than one occasion in the same patient (19, 27); six reported cases attended the ER between 10 and 60 days after the last catheter replacement. However, this event can also occur in patients with unknown neurological or urological pathology, and two incidental findings have been reported during laparotomy and two cases in the perioperative period of cesarean section (6, 12, 16, 17, 23, 26, 30). The most frequent clinical presentation was a pain in 65% of cases, although this may be absent, especially in patients with upper motor neuron disease due to impaired pain perception. A diagnostic confirmation has been in almost all cases radiological with ultrasound or CT-scan, although MRI has been described to visualize the balloon and tip of the catheter, hydroureteronephrosis, and in case of ureter rupture a urinoma and extravasation of contrast in the damaged area (20). In most cases, management has been conservative by catheter repositioning into the bladder and confirming fluid leakage. If a deflation of the balloon is not possible, a percutaneous attempt can be made; an endoscopic incision of the ureteral orifice has also been described (11). In case of ureteral injury, management might require DJ stent placement or surgical repair (10, 17, 18).

Our two patients suffered from CKD, recurrent UTI, and iterative catheter changes, both attended to the ER for pain, and oliguria within the first 24 hours after catheter replacement, patient one, who had a single functional kidney, had rapid deterioration of the general condition, patient 2 presented peri-catheter urine leakage. At the ER, AKI and UTI were found, CT scan revealed ureterohydronephrosis secondary to obstruction by the inflated catheter balloon in the distal ureter. In both cases, management consisted of deflating the balloon, carefully removing the catheter, and replacement; positioning was confirmed with saline flushing and ultrasound; hydration, antibiotic treatment, and control with ultrasound three days later, with clinical improvement of renal function and decrease of hydronephrosis. Three weeks later, an ultrasound confirmed both patients' complete resolution of hydronephrosis.

Use short-tipped catheters whenever possible. If urine does not drain spontaneously after catheter insertion, catheter irrigation should be performed before balloon inflation. Observe carefully if balloon inflation is accompanied by pain, although this may be absent in patients with sensory disorders. At the end of the procedure, gently pull out the catheter (22). In case of an SPC, it’s recommended, before deflating the balloon of the old catheter, gently pull the catheter completely and mark the catheter at the point where it enters the skin; this length will serve as a reference to confirm the depth of the new CSP or replace the CSP over a guidewire (19).

This review if the literature emphasize the importance of confirming the intravesical position of CSP and BIC after every replacement, inadvertent ureteral catheterization has the potential to provoke a serious clinical situation, although it is extremely uncommon. Medical staff should be aware of this possibility in order to be able to handle it quickly and efficiently.