1. Background

Beta-thalassemia (β-thalassemia) is an inherited disorder of hemoglobin synthesis caused by β-globin gene mutations and a common condition in Southeast Asian countries, such as Vietnam (1). The clinical and hematologic spectrum of β-thalassemia includes major, intermedia, and minor forms, where the severe form is divided into two subtypes, blood transfusion-dependent and transfusion-independent (2-4). The leading cause of mortality in thalassemia patients is heart failure secondary due to chronic iron overload, and patients usually die in the first or second decade of life (5-7). However, with acquiring a better understanding of the disease and advances in blood transfusion practice and iron chelation, the prognosis of β-thalassemia has been markedly improved.

The improved survival of β-thalassemia patients has enabled us to detect previously uncommon complications, such as kidney injury (KI). Chronic anemia, hypoxia, and iron overload are the main mechanisms of KI in β-thalassemia. In addition, undesirable effects of iron chelators may contribute to KI in β-thalassemia patients (8-11). In patients with β-thalassemia, serum ferritin levels >1000 µg/L indicate iron overload and are associated with increased mortality, higher risk of cardiac events, hepatic complications, and renal complications (12, 13). Chronic low-grade systemic inflammation is a condition characterized by persistently elevated circulating inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and is seen in coronary artery disease (14), renal disease (15, 16), and β-thalassemia (17).

2. Objectives

In order to better understand the mechanisms of KI in patients with β-thalassemia, we investigated if elevated plasma ferritin and CRP-hs levels could be related to KI in adults with β-thalassemia.

3. Methods

3.1. Patients

We included all 217 adults with β-thalassemia, including patients with major, intermedia, and minor clinical presentations, who were admitted and treated at Viet Tiep Friendship Hospital, Hai Phong, Vietnam, from January 2020 to December 2022. We excluded < 16-year-old patients, those with underlying kidney disease unrelated to β-thalassemia, patients suffering from acute inflammation (pneumonia, acute viral infections, etc.), and pregnant or lactating women. We provided written informed consent to all 142 remaining patients before their participation in the study.

All clinical and laboratory indices at the baseline time were collected. Based on interviews and follow-up records, the time of β-thalassemia detection, family history, blood transfusion status, and iron chelation drugs were documented. Comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes were also collected.

We also withdrew peripheral blood samples to determine the serum concentrations of glucose, urea, creatinine, cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-C, LDL-C, ALT, AST, electrolytes, iron, ferritin, transferrin, and CRP-hs. A complete blood count was also performed to determine the status and severity of anemia.

Urinary albumin was also determined for each patient, and then the urine albumin to creatinine ratio (uACR) was calculated. The glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated for all patients based on the Epi-CKD formula. Kidney injury was established when ACR was ≥ 3.0 mg/mmol based on KDIGO clinical practice guidelines (18).

We diviđe all 142 patients into two groups: group 1 (n = 19): KI patients with uACR ≥ 3.0 mg/mmol and group 2 (n = 123): Non-KI patients with uACR < 3.0 mg/mmol.

3.2. Statistical Analyses

We presented all continuous data by mean and standard deviation (for normally distributed data) or median and interquartile range (for non-normally distributed data). Two continuous variables were compared between the study groups using either the student t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test. For more than two groups, variables were compared using the ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test. We presented categorical data by frequency and percentage and compared them between the study groups using the chi-square test. Multivariable-adjusted regression analysis was used to identify independent factors related to KI. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve models were performed to identify the predictors of KI. The data were analyzed by Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20.0 software (Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

The results (Table 1) showed that the ratios of transfusion-dependent patients, β-thalassemia major, increased ALT, and increased AST were significantly higher in the KI group than in the non-KI group (P < 0.05). The median values of serum iron, ferritin, CRP-hs, urine albumin, and uACR were also significantly higher in patients with KI than in those without KI (P < 0.01). Moreover, blood hemoglobin and urine creatinine concentrations were significantly lower in the KI group than in the non-KI group (P < 0.01).

| Clinical and Laboratory Indices | Total (N = 142) | KI (N = 19) | Non-KI (N = 123) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 30.5 (24 - 41) | 29 (25 - 56) | 31 (24 - 41) | 0.881 |

| Number of males | 40 (28.2) | 5 (26.3) | 35 (28.5) | 0.847 |

| Disease detection time (y) | 0.081 | |||

| First time | 59 (41.5) | 4 (21.1) | 55 (44.7) | |

| 1 to < 5 | 18 (12.7) | 1 (5.3) | 17 (13.8) | |

| 5 to < 10 | 24 (16.9) | 4 (21.1) | 20 (16.3) | |

| 10 to < 15 | 15 (10.6) | 4 (21.1) | 11 (8.9) | |

| ≥ 15 | 26 (18.3) | 6 (31.6) | 20 (16.3) | |

| Use of iron chelators | 0.134 | |||

| Yes | 46 (32.4) | 9 (47.4) | 37 (30.1) | |

| No | 96 (67.6) | 10 (52.6) | 86 (69.9) | |

| Blood transfusion | 0.011 | |||

| No | 66 (46.5) | 4 (21.1) | 62 (50.4) | |

| NTD | 53 (37.3) | 8 (42.1) | 45 (36.6) | |

| TD | 23 (16.2) | 7 (36.8) | 16 (13) | |

| Family history | 1.000 | |||

| Yes | 11 (7.7) | 1 (5.3) | 10 (8.1) | |

| No | 131 (92.3) | 18 (94.7) | 113 (91.9) | |

| Severity of disease | 0.029 | |||

| Minor | 83 (58.5) | 6 (31.6) | 77 (62.6) | |

| Intermedia | 25 (17.6) | 5 (26.3) | 20 (16.3) | |

| Major | 34 (23.9) | 8 (42.1) | 26 (21.1) | |

| BMI | 0.375 | |||

| < 18.5 | 42 (29.6) | 8 (42.1) | 34 (27.6) | |

| 18.5 to 22.9 | 95 (66.9) | 11 (57.9) | 84 (68.3) | |

| ≥ 23.0 | 5 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.1) | |

| Mean | 19.57 ± 2.01 | 18.91 ± 1.63 | 19.68 ± 2.05 | 0.124 |

| Hypertension | 0.246 | |||

| Yes | 17 (12) | 4 (21.1) | 13 (10.6) | |

| No | 125 (88) | 15 (78.9) | 110 (89.4) | |

| Diabetic mellitus | 1.000 | |||

| Yes | 15 (10.6) | 2 (10.5) | 13 (10.6) | |

| No | 127 (89.4) | 17 (89.5) | 110 (89.4) | |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | ||||

| ≥ 7.0 | 12 (8.5) | 2 (10.5) | 10 (8.2) | 0.665 |

| Median | 5 (4.4 - 5.8) | 5.25 (4.63 - 5.89) | 5 (4.36 - 5.8) | 0.452 |

| Plasma protein (g/L) | 72.19 ± 7.21 | 77.04 ± 8.99 | 71.44 ± 6.62 | 0.001 |

| Plasma albumin (g/L) | 40.08 ± 5.03 | 41.59 ± 5.42 | 39.85 ± 4.95 | 0.162 |

| ALT (UI/L) | ||||

| > 40.0 | 42 (29.6) | 10 (52.6) | 32 (26) | 0.018 |

| Median | 23 (14.42 - 47.32) | 47 (26 - 85.2) | 21.4 (14 - 43) | < 0.001 |

| AST (UI/L) | ||||

| > 40.0 | 44 (31) | 12 (63.2) | 32 (26) | 0.001 |

| Median | 31 (22.07 - 50) | 58.7 (34.6 - 98.4) | 28.5 (21.4 - 43.4) | < 0.001 |

| Na+ (mmol/L) | 135.97 ± 3.79 | 135.7 ± 2.33 | 136.01 ± 3.97 | 0.639 |

| K+ (mmol/L) | 3.74 ± 0.30 | 3.85 ± 0.39 | 3.72 ± 0.28 | 0.07 |

| Anemia | 141 (99.3) | 19 (100) | 122 (99.2) | 1.000 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 79.88 ± 16.03 | 69.15 ± 10.95 | 81.53 ± 16.09 | 0.002 |

| Hematocrit (L/L) | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.003 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 4.43 (3.6 - 5.45) | 4.5 (3.87 - 6.22) | 4.4 (3.55 - 5.34) | 0.221 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 53.4 (46.2 - 63.75) | 53.6 (42.1 - 58.3) | 53.4 (46.3 - 64.1) | 0.590 |

| eGFR | ||||

| < 60 mL/min | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| Mean | 120.32 ± 20.28 | 122.26 ± 22.44 | 120.02 ± 20.0 | 0.656 |

| Iron (µmol/L) | 22.25 (14.05 - 33.85) | 28.1 (24.9 - 41.6) | 20 (12.7 - 32.1) | 0.002 |

| Ferritin (µg/L) | 534.25 (174.74 - 1541.5) | 2468 (741.7 - 5125) | 400.27 (138.9 - 1392.7) | < 0.001 |

| Transferrin (G/L) | 1.88 ± 0.63 | 1.69 ± 0.49 | 1.91 ± 0.64 | 0.167 |

| CRP-hs (mg/L) | 1.2 (0.6 - 2.6) | 3.5 (2.6 - 4.9) | 1.1 (0.5 - 2.1) | < 0.001 |

| Urine Protein (g/24hs) | 0.07 (0.05 - 0.17) | 0.23 (0.07 - 0.56) | 0.07 (0.04 - 0.12) | 0.001 |

| Urine albumin (mg/L) | 6.44 (4.26 - 10.92) | 24.52 (15.5 - 54.23) | 5.56 (3.94 - 8.43) | < 0.001 |

| Urine creatinine (mmol/L) | 7.21 (4.45 - 10.04) | 5.23 (3.73 - 6.58) | 7.68 (4.73 - 10.65) | 0.01 |

| uACR (mg/mmol) | 0.81 (0.52 - 1.6) | 4.78 (3.84 - 8.79) | 0.71 (0.5 - 1.16) | < 0.001 |

| KI | 19 (13.4) | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: NTD, non-transfusion-dependent; TD, Transfusion-dependent; BMI, body mass index; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CRP-hs, C reactive protein-high sensitive; uACR, urine albumin creatinine ratio; KI, kidney injury.

a Values are presented as No. (%).

As shown in Table 2, elevated plasma ferritin, increased CRP-hs, low hemoglobin, and less using iron chelating agents were independent factors associated with KI in adults with β-thalassemia.

| Variables | OR | 95% Cl | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 0.944 | 0.893 - 0.998 | 0.044 |

| Ferritin (µg/L) | 1.001 | 1.000 - 1.001 | 0.002 |

| CRP-hs (mg/L) | 3.301 | 1.945 - 5.602 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 1.165 | 1.009 - 1.346 | 0.037 |

| Using iron chelating agents | 0.137 | 0.025 - 0.766 | 0.024 |

Abbreviations: KI, kidney injury; CRP-hs, C reactive protein-high sensitive.

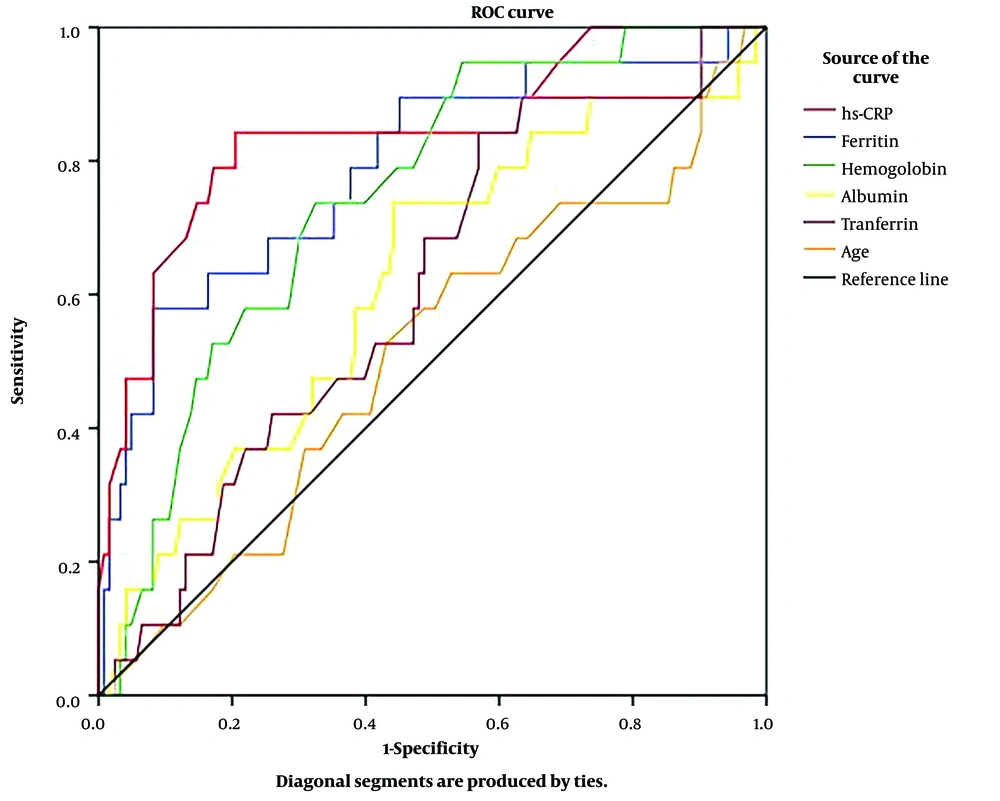

Based on the ROC curve (Figure 1), plasma CRP-hs, ferritin, and hemoglobin had good predictive values for KI in adults with β-thalassemia (P < 0.001).

Receiver-operating characteristic curves of age, plasma albumin, hemoglobin, ferritin, transferrin, and CRP-hs for predicting KI in adults with β-thalassemia. (CRP-hs: AUC = 0.841; P < 0.001; cut-off value = 2.35 mg/L; sensitivity = 84.2%; specificity = 79.5%, ferritin: AUC = 0.789; P < 0.001; cut-off value = 2394.95 µg/L; sensitivity = 57.9%; specificity = 91.9%, hemoglobin: AUC = 0.747; P = 0.001; cut-off value = 76.5 g/L; sensitivity = 73.7%; specificity = 67.5%, albumin: AUC = 0.619; P > 0.05, transferrin: AUC = 0.608; P > 0.05, age: AUC = 0.511; P > 0.05).

5. Discussion

5.1. Ratio of KI in Adults with β-thalassemia

Based on urine ACR and according to KDIGO 2012 classification, 19 out of 142 (13.4%) patients had KI (Table 1). Studies on renal function (glomerulus and tubulous) and KI in β-thalassemia patients are scarce. Plasma creatinine is a reliable indicator to assess GFR in patients, and cystatin C, which is not excreted or reabsorbed into the bloodstream by renal tubules, is a sensitive biomarker for GFR. All cells in the body continuously produce cystatin C and cystatin C production is not affected by age, gender, or muscle mass (19, 20). Therefore, many researchers use cystatin C as an early and reliable marker of glomerular filtration dysfunction (21, 22). In addition, urinary β2 microglobulin, which is freely filtered by the glomerulus, reabsorbed by renal tubules, and then eliminated, is also recommended for assessing early renal dysfunction in β-thalassemia patients (23, 24).

Regarding renal tubular function, other classic indicators that can be used as early predictors of renal tubular damage in β-thalassemia patients include the fraction excretion of sodium, potassium, calcium, urine NGAL, and KIM-1 (25, 26). Also, uACR is a valuable indirect indicator of glomerular injury (albumin) and glomerular filtration function (creatinine). This is an easy-to-follow biomarker that has been widely applied in clinical practice. Many authors have also used this index to evaluate KI in β-thalassemia patients (25, 26). An interesting point observed in our study was that although 13.4% of the patients were found to have KI, only 1/142 patients (0.7%) had renal dysfunction (GFR < 60 mL/min) based on the glomerular filtration rate (Table 1). Based on these results, we recommend clinicians consider uACR during each patient visit to detect renal complications in β-thalassemia patients.

5.2. Link of Plasma CRP-hs and Ferritin with KI in Adults with β-thalassemia.

Renal complications in β-thalassemia patients are infrequent. We found that only 13.4% of the patients in this study had KI (Table 1). However, the patient’s prognosis will not be good when this complication occurs. We divided patients into 2 groups (i.e., KI and non-KI) and identified modifiable risk factors that can be regarded during the treatment process to reduce the rate of this complication. Although there were many univariate indicators related to renal complications (Table 1), multivariate analysis revealed only 2 independent indicators of KI; plasma ferritin (P = 0.002) and CRP-hs (P < 0.001) (Table 2). According to ROC analysis, the results showed that plasma ferritin and CRP-hs were valuable predictors of renal complications in β-thalassemia patients with AUCs of 0.789 and 0.841, respectively (P < 0.001, Figure 1). These findings suggest that we can rely on plasma ferritin and CRP-hs levels to predict renal complications in adults with β-thalassemia.

Plasma ferritin levels in β-thalassemia patients reflect iron overload (ferritin levels > 1000 µg/L) (12, 13). Iron homeostasis is a complicated process, and daily absorption and excretion are maintained at approximately 2 mg/day. Because humans cannot actively excrete iron, excess iron from blood transfusions will be accumulated in body tissues. In β-thalassemia patients, among important factors associated with KI have been noted to be anemia, iron overload, and using iron chelators (27, 28). Here, we identified that elevated levels of CRP-hs, an indicator of subclinical inflammation, were closely related to renal complications in adults with β-thalassemia (Table 1, and 2, Figure 1). Elevated plasma levels of CRP-hs often result from subclinical inflammatory processes, including endothelial injury and deposition of immune complexes in renal parenchyma (29, 30). Our results suggested that plasma hs-CRP was involved in the pathogenesis of KI in β-thalassemia patients. Chronic anemia/hypoxia leads to endothelial and epithelial damage, tubulointerstitial injury, glomerulosclerosis due to iron overload, tubuloglomerular feedback, and hemodynamic changes due to iron chelation (8, 10). The final consequences of chronic anemia, iron overload, and iron chelator toxicity will be damage to glomeruli and renal tubulointerstitium (10).

Although our results met our research objectives, this study had some limitations. First, we did not use these new biomarkers to assess glomerular and tubular dysfunction. Second, we did not analyze the relationship of KI with disease severity and the use of iron-chelating drugs.

5.3. Conclusions

The rate of KI in adults with β-thalassemia was 13.4%. Plasma ferritin and CRP-hs had good predictive values for KI in β-thalassemia patients.