1. Introduction

After being first reported by Goodwin et al. percutaneous renal access has become an established procedure during the past few decades (1). Based on a review of the literature, injury to the biliary tract rarely occurs after percutaneous renal procedures but can lead to serious outcomes including death. Early recognition and intervention is critical to minimize the morbidity and mortality associated with this type of biliary tract injury. The evolution of peritonitis, because of delayed intervention, will make laparotomy inevitable and can potentially be associated with serious complications. In review of the few reported cases, all of these patients with a biliary tract injury underwent a cholecystectomy via either a laparoscopic (2, 3) or open procedure (4-6). Herein we report the first case of biliary tract injury following a renal-targeted percutaneous procedure managed minimally invasively by insertion of a percutaneous cholecystostomy tube.

2. Case Presentation

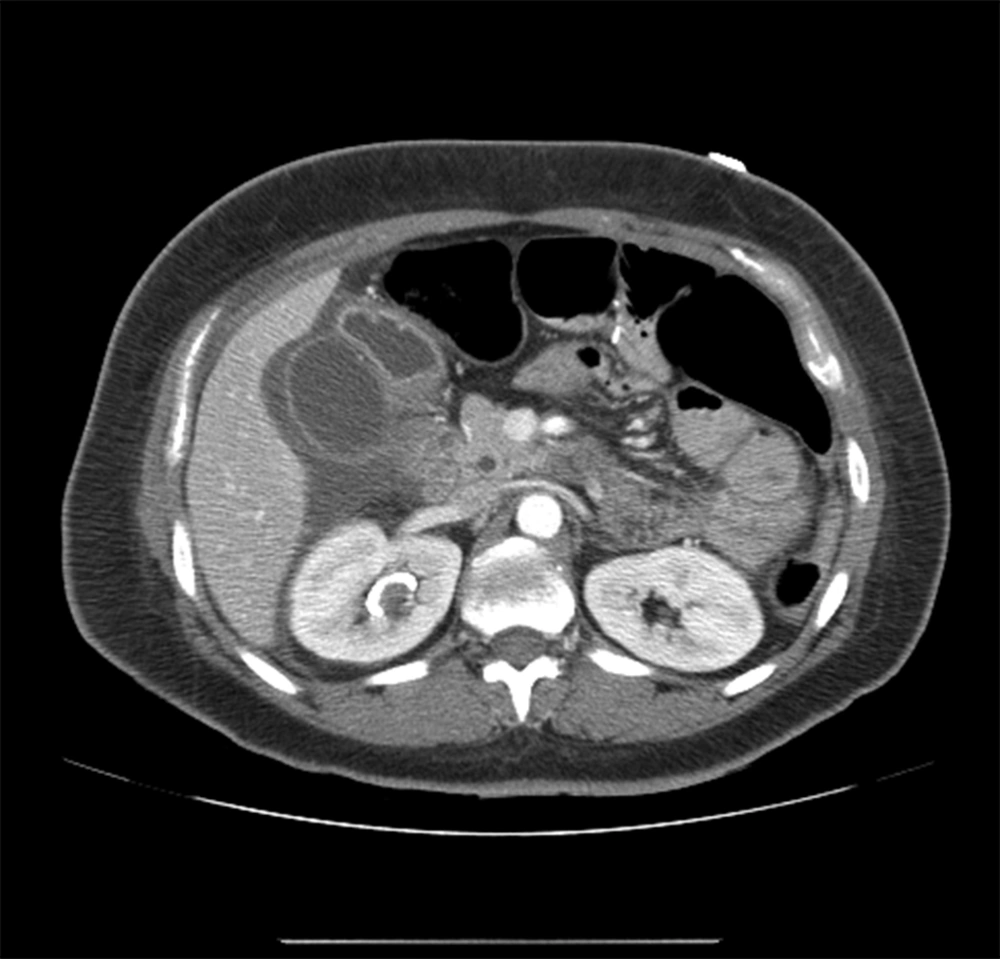

A 39-year old woman, with past medical history of gastric bypass, was scheduled to undergo percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) for a 4 cm right renal pelvic calculus with partial staghorn extension to lower pole. At the time of passage of an 18-gauge needle to the right kidney under fluoroscopy guidance, bile stained fluid was aspirated and the procedure aborted. A large caliber ureteral stent and Foley catheter were placed to maximize urinary drainage and the patient admitted for observation. Overnight, the patient developed abdominal pain and became tachycardic and tachypenic. Laboratory studies showed an increased white cell count (19.9 × 103 per microliter), while liver function tests stayed in normal range with total and direct bilirubin 0.6 mg/dL (0.2-1.3) and 0.2 mg/dL (0-0.4) respectively. Subsequently abdominal CT scan was performed which showed a large fluid collection in the right peri-hepatic and peri-nephric area (Figure 1). Interventional radiology was consulted to place a sub-hepatic drain.

Despite drainage of about 1 liter of bile stained fluid over the next 24 hours, the patient remained tachycardic and tachypenic with complaints of severe abdominal pain. General surgery was consulted and placement of a percutaneous cholecystostomy tube was recommended. Following this, the drainage from the sub-hepatic drain stopped and her clinical status improved significantly. Follow up ultrasonography revealed decreased peri-hepatic collection and the sub-hepatic drain was removed after three days. The patient was then discharged home in stable condition with the cholecystostomy tube. On post procedure day 17, a tube cholangiogram revealed good flow of contrast into the duodenum without any evidence of leak or filling defect. Subsequently the tube was clamped and later removed in general surgery clinic. The kidney stone was later treated with staged ureteroscopy. At 6 months follow up, the patient is doing well without any complications and is stone free.

3. Discussion

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy has comparable results to open surgery with the advantage of being less invasive and having a shorter hospital stay (7). Although PCNL is generally considered a safe procedure, it can still be associated with serious and potentially life threatening complications. These include urinary tract infection, bleeding and damage to surrounding structures like colonic perforation, duodenal injury and pleural injury (8, 9).

Injury to the biliary tract during percutaneous renal access is a rare complication. In a study of 8000 ultrasound-guided punctures, only 4 incidents were reported and none of them was with a renal puncture target (10). In review of the literature, there are few cases of biliary tract injury during isolated nephrostomy (6) or percutaneous nephrolithotomy (2, 4, 5), all of which have been managed by cholecystectomy.

Kontothanassis et al. (6) reported a case of gall bladder injury during an ultrasonography-guided nephrostomy done for urinary tract obstruction. Greenish fluid was noted during the procedure and the patient developed signs of abdominal distension and tenderness over the following 12 hours. The patient underwent a laparotomy and a cholecystectomy was performed.

Fisher et al. (2) reported another case of biliary tract injury after percutaneous access during PCNL. The patient developed abdominal discomfort and signs of peritoneal irritation on physical exam while a CT scan revealed peri-cholecystic and sub-hepatic fluid collection. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed. Although gallbladder perforation secondary to percutaneous liver biopsy has been reported to be managed by insertion of percutaneous cholecystostomy tube, to our knowledge all reported cases of biliary injury during percutaneous renal accesses have been managed with cholecystectomy.

While bile peritonitis after PCNL is rare, it should always be kept in mind. Injury to the biliary tract should be suspected in patients who develop abdominal pain, peritoneal signs or any component of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) post operatively. Aspiration of bile during procedure makes the diagnosis more likely. In our study as well as some previous case reports (6) the presence of "greenish fluid” was a clue to the biliary tract injury, although this finding does not always exist (2-4) and careful follow up is necessary after every percutaneous procedure. Certainly, prompt recognition of biliary tract puncture prior to renal access tract dilation is crucial to prevent further biliary tract damage.

Although some articles advise immediate cholecystectomy in gallbladder injuries during percutaneous nephrostomy (2), detection and appropriate drainage in a timely manner may avoid the need for cholecystectomy. One should consider this option even in the absence of peritonitis, if considerable amount of bile-colored fluid was initially aspirated during the procedure. Performing endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) and stent placement across the Sphincter of Oddi is a well-known and standard treatment approach for small bile leaks, such as cystic duct stump leaks. This allows bile to preferentially drain to the duodenum, so that the leak can heal. In this case with a history of gastric bypass, the option of performing an ERCP was significantly more complicated. As such, the decision was made to place a percutaneous cholecystectomy tube, with the same goal of allowing for preferential drainage of bile through the cholecystectomy tube rather than the area of leak. The patient’s symptoms resolved almost immediately, and the leak was resolved without ever needing a cholecystectomy. The ease of management and the lower risk of peri-operative complications with better outcome make cholecystectomy a preferential option over laparotomy and cholecystectomy. If a biliary tract injury is suspected during percutaneous renal procedures, diverting the bile away from the leak may resolve the problem without the need for a cholecystectomy. Ideally this can be done with ERCP and a stent, but in cases where this is not technically feasible; a percutaneous cholecystostomy can be successful at accomplishing the same result.