1. Context

Uric acid is the poorly soluble circulating end product of the purine nucleotide metabolism in human beings. A decrease in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) contributes to hyperuricemia (HUA), which is frequently observed in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (1-4). Most mammals are endowed with an additional enzyme, urate oxidase, which converts uric acid to allantoin for excretion, whereas humans have evolutionarily acquired distinct gene mutations that render this latter enzyme inactive, resulting in the inability to produce allantoin (5). Therefore, the physiologic catabolism of endogenous and dietary purine nucleotides ends with uric acid in humans. However, the presence of ischemic stress and/or excess production of reactive oxygen species can independently advance uric acid oxidation to allantoin and other breakdown products (6). Kidneys are responsible for the excretion of two-thirds of the daily uric acid, with the remaining one-third being excreted through the gastrointestinal tract. More than 90% of all cases of HUA are the result of the impaired renal excretion of uric acid (7). It has been demonstrated that the prevalence of HUA rises in parallel with the GFR decline, which is present in 40% to 60% of patients with CKD stages I to III and 70% of patients with CKD stage IV or stage V (8, 9). In patients receiving dialysis, the prevalence of HUA also rises in parallel with dialysis vintage (10).

HUA is defined as a serum uric acid level > 7.0 mg/dL in males and ˃ 6.0 mg/dL in females (11). The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) definition and classification were accepted, with clarifications. CKD is defined as kidney damage or a GFR ˂ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months or more, irrespective of the cause. Kidney damage in many kidney diseases can be ascertained by the presence of albuminuria, defined as an albumin-to-creatinine ratio ˃ 30 mg/g in 2 of 3 spot urine specimens. The GFR can be estimated from calibrated serum creatinine and estimating equation such as the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation or the Cockcroft-Gault formula. Kidney disease severity is classified into 5 categories according to the level of the GFR (Table 1).

| Stage | Description | Classification by Severity | Classification by Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kidney damage with normal or ↑GFR | GFR ≥ 90 | T if kidney transplant recipient |

| 2 | Kidney damage with mild ↓in GFR | GFR of 60 - 89 | T if kidney transplant recipient |

| 3 | Moderate ↓in GFR | GFR of 30 - 59 | T if kidney transplant recipient |

| 4 | Severe ↓in GFR | GFR of 15 - 29 | T if kidney transplant recipient |

| 5 | Kidney failure | GFR ˂ 15 (or dialysis) | D if dialysis |

aAbbreviations: GFR, Glomerular filtration rate; KDOQI, Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative, KDIGO, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes.

CKD has become a global public health problem because of its high prevalence and the accompanying increase in the risk of end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular disease, and premature death (12). Uric acid crystals have the capacity to adhere to the surface of renal epithelial cells (13) and induce an acute inflammatory response in such cell lines (14). In addition to an increased risk of kidney stone formation, such effects have been shown to reduce the GFR (15).

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Pathophysiology

2.1.1. Pathophysiology of Hyperuricemia

Uric acid in the blood is saturated at 6.4 - 6.8 mg/dL at ambient conditions and the upper limit of solubility placed at 7 mg/dL. Urate is freely filtered, reabsorbed, and secreted at the glomerulus, and again reabsorbed in the proximal tubule. A urate or anion exchanger (URAT1) has been identified in the brush-border membrane of the kidneys and is inhibited by an angiotensin II receptor blocker. A human organic anion transporter (hOAT1) has been found to be inhibited by both uricosuric drugs and antiuricosuric drugs, while another urate transporter (UAT) has been found to facilitate urate efflux out of the cells. These transporters may facilitate the reabsorption, secretion, and reabsorption pattern of the renal handling of urate.

HUA may occur because of decreased excretion, increased production, or a combination of both mechanisms. Decreased excretion accounts for most causes of HUA. Urate handling by the kidneys involves filtration, reabsorption, and secretion at the glomerulus, and finally, postsecretory reabsorption. Altered uric acid excretion can result from decreased glomerular filtration, decreased tubular secretion, or enhanced tubular reabsorption. While decreased urate filtration may not cause primary HUA, it can contribute to the HUA of renal insufficiency.

Glycogenoses types III, IV, and VII can result in HUA from the excessive degradation of skeletal muscle ATP. Combined mechanisms can also cause HUA. The most common cause under this group is alcohol consumption (16), which results in the accelerated hepatic breakdown of ATP and the generation of organic acids that compete with urate for tubular secretion. Enzymatic defects such as glycogenoses type I and aldolase-B deficiency are other causes of HUA that result from a combination of overproduction and underexcretion.

2.1.2. Pathophysiological Relationship Between Uric Acid and Chronic Kidney Disease

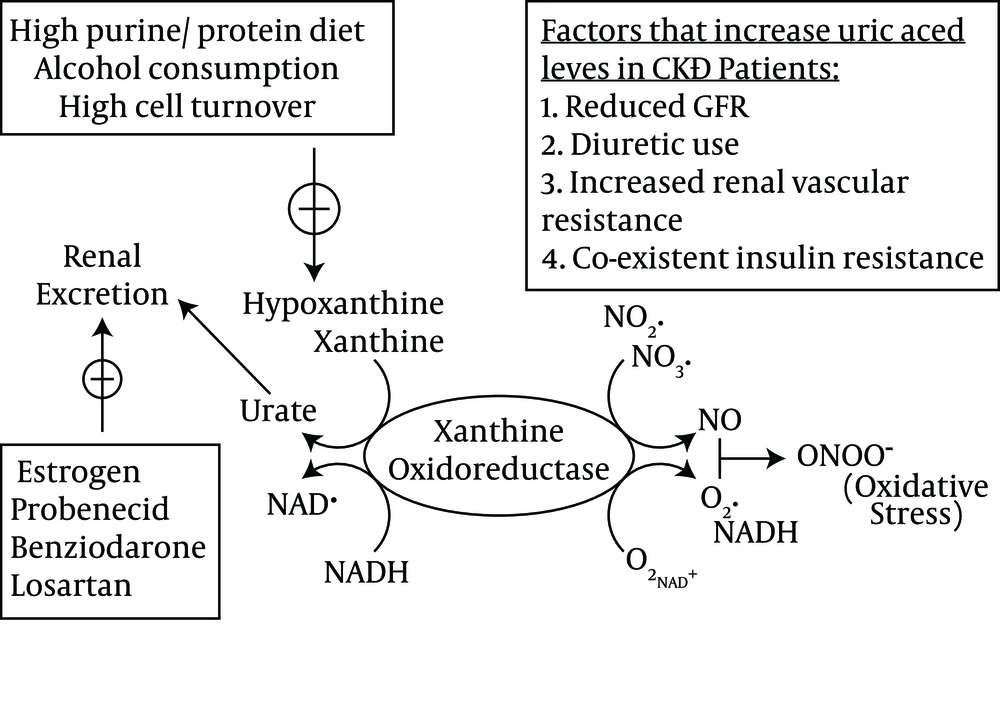

Urate is filtered readily by the glomerulus and subsequently reabsorbed by the proximal tubular cells of the kidney, and the normal fractional excretion of uric acid is approximately 10% (17). Human kidneys reabsorb urate, which may contribute to the higher serum uric acid levels in humans compared with other species. In addition, uricase mutation prevents further uric acid degradation in human beings (18). The human urate transporter, i.e. URAT1 (encoded by the SLC22A12 gene), facilitates uric acid reabsorption in the proximal convoluted tubule (19). A recent study showed that GLUT9 (encoded by SLC2A9), which is a member of the glucose transporter family, could be a major regulator of uric acid homeostasis (20). Uric acid homeostasis and the main factors that lead to increased serum uric acid levels in CKD are schematically depicted in Figure 1.

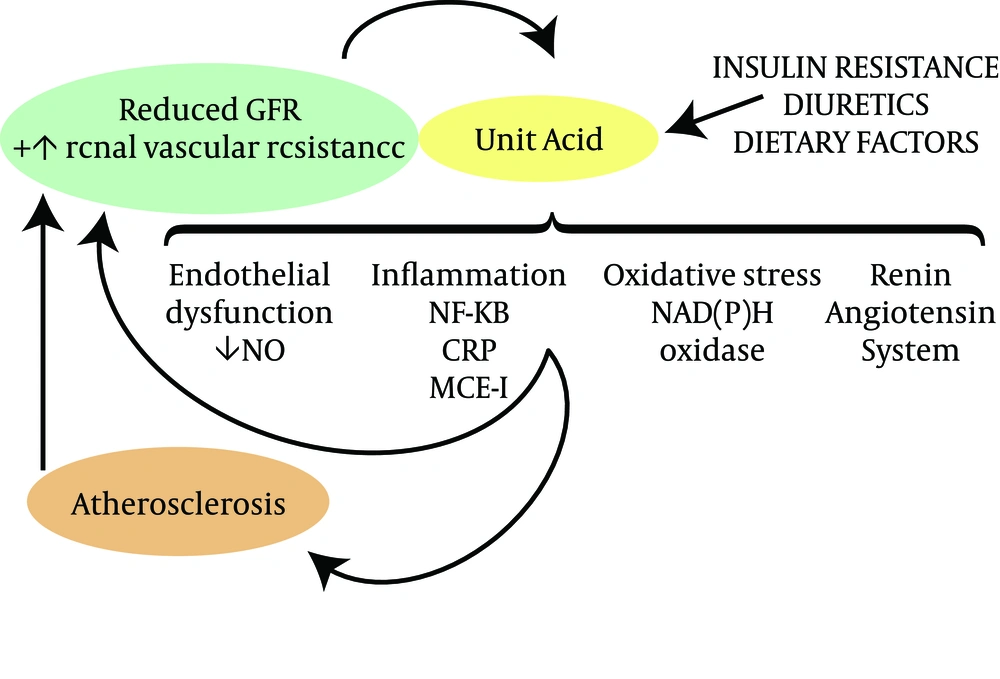

Uric acid has been shown to activate the cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 and inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), leading to the inhibition of proximal tubular cellular proliferation in vitro (21). Increasing serum uric acid levels include systemic cytokine production, i.e. tumor necrosis factor α (22), and the local expression of chemokines, i.e. monocyte chemotactic protein 1 in the kidney (23, 24) and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) in blood vessels (24). The withdrawal of uric acid lowering therapy was found to increase urinary transforming growth factor-β1 in a group of HUA patients with CKD (25). The putative mechanisms by which increased serum uric acid levels may contribute to CKD onset and progression are shown in Figure 2.

Increasing uric acid levels could induce oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, resulting in the development of both systemic and glomerular hypertension in association with elevated renal vascular resistance and reduced renal blood flow (26, 27). Obesity and the metabolic syndrome are the most common risk factors for CKD and are strongly associated with HUA probably as a consequence of insulin resistance and the effects of insulin to reduce urinary urate excretion (28). Hypertension is also commonly associated with renal vasoconstriction, which also leads to uric acid retention (29). Low-level intoxication with lead and cadmium can also raise serum uric acid levels by blocking the renal excretion of uric acid. Wang et al. (30) performed a meta-analysis based on 11 papers with a total of 753 participants and reported that uric acid lowering is associated with a significant reduction in the serum creatinine concentration and an increase in the estimated GFR.

In one study, HUA rose to 58% among the patients receiving antihypertensive therapy, particularly in those receiving diuretics (31). High plasma uric acid levels are common in patients with arterial hypertension (29, 32). Blood pressure elevation was found to be associated with the development of an initial salt-insensitive hypertension that was reversible with the restoration of normal urate levels (33). Serum uric acid influences many of the proposed mechanisms of acute kidney injury such as renal vasoconstriction. Impaired autoregulation has proinflammatory and antiangiogenic properties (34) and plays a key role in both innate and adaptive immune responses (35). Elevated serum uric acid levels decrease the renal blood flow and the GFR. Vascular and endothelial functions are known to have a major role in driving CKD (36, 37). Moreover, an elevated serum uric acid level is strongly associated with endothelial dysfunction. Endothelial function assessed by the flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery or acetylcholine-induced coronary blood flow is reported to be inversely correlated with serum uric acid levels (38-40).

3. Results

3.1. Diagnosis

3.1.1. Diagnosis of Hyperuricemia

The symptoms of HUA that cause gout include a painful joint, usually the toes. The joint will become red and swollen and the pain can be intense. Gout can also affect the ankles, knees, hands, and wrists. During the physical examination, the doctor will examine the painful joints and ask about the pain and swelling to determine whether the HUA is from gout. Blood test is also done to determine the amount of uric acid in the blood. A simple blood test will show increased levels of uric acid, which can cause kidney stones in addition to gout. For those who have kidney disease, the level of uric acid in the blood can indicate a worsening condition. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy for cancer can also cause the level of uric acid to increase.

Joint fluid is drawn for the crystals of HUA. In this test, the doctor withdraws fluid from the affected joint and examines it under a microscope. Swollen and painful joints may be caused by crystals, which form when the body cannot dispose of uric acid. The uric acid that remains will form crystals, which can be seen under the microscope. The crystals are pointy and cause a great deal of pain when surrounding the joint. The crystals, named urate crystals, are also responsible for certain types of kidney stones.

3.1.2. Interventional Studies in Hyperuricemia and Chronic Kidney Disease

Cyclosporine is a widely used drug for immunosuppression post transplantation and to a lesser degree in patients with other autoimmune diseases. It has been strongly associated with the development of HUA and gout (41). However, the mechanism for Cyclosporine’s strong association with HUA is unclear and may include an inhibitory effect on urate secretion (42). Tacrolimus also commonly is used in transplantation immunosuppressive regimens and has been reported to increase serum urate levels in a manner similar to Cyclosporine (43). However, data from the US Renal Data System in combination with Medicare claims data suggest that it may induce less clinical gout in kidney transplantation recipients (hazard ratio for Cyclosporine versus Tacrolimus: 1.24; 95% confidence interval: 1.06 to 1.45) (44). Other drugs and toxins associated with HUA and gout include lead, Pyrazinamide, Ethambutol, and niacin (45).

Xanthine oxidase inhibitors such as Allopurinol or Febuxostat are the preferred agents to decrease uric acid levels due to their effectiveness in both overproducers and undersecretors of uric acid. Allopurinol is metabolized by xanthine oxidase to oxypurinol and both substrates act to inhibit xanthine oxidase (46). Patients with CKD may be at an increased risk of toxicity with Allopurinol because oxypurinol is cleared by the kidney (47). It is widely recommended to start with low dosages of Allopurinol in patients with CKD and slowly titrate it to an effective dose. Febuxostat has been shown to be safe and effective for decreasing serum uric acid levels (48) and is deemed an alternative to Allopurinol in HUA patients unable to tolerate the latter. Other agents that can be used to decrease uric acid levels include uricosuric agents such as Probenecid and Benzbromarone. In a small randomized trial by Siu et al. (49), 54 HUA patients with mild to moderate CKD were assigned to Allopurinol (100 - 300 mg/d with the goal of normalizing serum uric acid levels) versus no therapy and followed up for 12 months. At the end of follow-up, a significantly larger number of participants in the control group achieved the combined end point of a serum creatinine level increase ≥ 40%, dialysis, or death. More recently, a larger study conducted by Goicoechea et al. (50) included 113 HUA patients with CKD randomly assigned to the Allopurinol group (100 mg/d) and the control group. At the end of the 2-year follow-up, the estimated GFR decreased in the control group and the GFR increased in the Allopurinol group.

Some recent studies have suggested that treating HUA may prevent or delay the onset of CKD. A randomized double-blinded study by Feig et al. (51) showed that treating HUA in adolescents with newly diagnosed hypertension was effective at lowering the blood pressure. Similar to the studies mentioned, Allopurinol was used to decrease serum uric acid levels and resulted in significant improvements in the systolic and diastolic blood pressures compared with a placebo. Kanbay et al. (52) conducted a small case-controlled study on 59 HUA individuals with an estimated GFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 treated with 300 mg of Allopurinol daily for a 3-month period and reported improvements in the systolic and diastolic blood pressures as well as a significant increase in the estimated GFR. Recently, one open-label randomized controlled trial conducted by Shi et al. (53) evaluated Allopurinol treatment in 40 patients with IgA nephropathy. Allopurinol did not significantly alter kidney disease progression or proteinuria, but the blood pressure was significantly improved in these patients after 6 months of treatment.

Allopurinol therapy can be associated with fatal Stevens-Johnson syndrome, while screening for HLA-B68 may allow the elimination of subjects at highest risk for this condition (54). The new xanthine oxidase inhibitor, i.e. Febuxostat, does not appear to be associated with Stevens-Johnson-syndrome to date, and its dosage does not need to be modified in CKD. It may also be more effective at lowering the uric acid level in the setting of CKD (55).

4. Conclusions

HUA is common in CKD. Many evidence-based studies have suggested that uric acid itself may harm patients with CKD by increasing inflammation and CKD progression, but the issue is still shrouded in controversy. The prevalence of CKD continues to increase, and it is likely that the management of HUA and gout will continue to be a challenge in these patients. Diet, polypharmacy, and lifestyle issues are important aspects to discuss with patients. Special attention should be given to specific contraindications to certain drugs and the possibility of infectious arthritis, especially relevant in such complex patients as those with CKD or transplantation recipients. Allopurinol often is the treatment of choice for patients with chronic gout given its effectiveness, even in the setting of a decreased GFR. However, caution should be exercised in this setting, with low starting doses and conservative dose escalations tailored to the serum urate concentration.