1. Context

Hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation are the main strategies for the treatment of ESRD patients. Due to the increasing number of ESRD patients, healthcare decision-makers should pay particular attention to it. At the end of 2016 it was estimated that the number of ESRD patients was 3730000 and by considering the annual growth of 5% - 6% of these patients compared with the growth of 1/1% of world population growth, ESRD is one of the priorities of the healthcare systems (1).

The average prevalence in Iran is 680 per million, which is more than the global average. By the end of 2016, the number of ESRD patients undergoing renal replacement therapy is more than 58000, with about 29200 hemodialysis patients, 1624 peritoneal dialyses, and about 27000 transplant patients (2). Many advances in kidney surgeries, which introduce new drugs and medical supplies, have contributed to enhancing the patient’s quality of life (3).

Kidney transplantation is regarded as the selective option for patients with ESRD; progress in surgical care methods, tissue typing, and immunosuppression management has enhanced the result of kidney transplant recipients (4). The ultimate aim of kidney transplantation is to have an unlimited number of organs for all potential recipients with normal graft function and no rejection (5). However, patients may lead to confront new difficulties and concerns by transplantation, which can enhance the patient's quality of life. It should be noted that transplantation is something more than getting a new organ; the recipients should change their vision and physically, psychologically, and socially adapted to their new life; there is a deep gap between the reality and unrealistic expectations of the patient and his relatives in the post-transplantation period (6).

Dr. Mohammad Sanadi Zadeh and his colleagues conducted the first kidney transplant in Iran in 1967 (7). The most important challenges in this field include a late diagnosis of brain death, cultural problems in brain death issue, and lack the hospital equipment and specialized staff. However, the Iranian model, a governmental controlled transplant program, was inaugurated for resolving organ shortage in transplantation. The aim of this study was to review the challenges of the kidney transplantation model in Iran and to provide recommendations for the successful operation of the model.

1.1. Iranian Model of Kidney Transplantation

During the past two decades Iran has had one of the most successful kidney transplant models in the world, which possesses some distinct features that are described in Table 1.

| No Coercion | Donors Age > 25 Years |

|---|---|

| Donors to be true volunteers (altruistic or emotionally related donors) | No commercialism |

| Donors given rewarded gifts supported by the government | No matchmaker or broker |

| Donors given one year of free health insurance | No financial benefit for transplant team |

| No foreign recipients for Iranian donors | No foreign donors for Iranian recipients |

| Written consent will be obtained from donors' parents and/or spouse | Short waiting list |

| Rich and poor patients are equally transplanted | Written contest will be obtained from the donor |

Characteristics of “Iran Model” for Living Unrelated Donor Renal Transplantation (8)

The government and charity funds support this model and pay the costs of the transplantation process and medication (9). Potential kidney recipients were evaluated by nephrologists and after required tests, they were referred to the Society for Supporting Dialysis and Transplantation Patients. The society works as a connection between donors and recipients, moreover, experts in the transplant centers are not involved in distinguishing probable donors. The agreement between the parents and/or spouse is necessary. The potential donors should be in good condition and between 25 and 40 years old. There is no broker means in this model. The transplantation process is performed by highly trained specialists in selective centers, often university hospitals, and accredited by the Ministry of Health (10).

1.2. Kidney Transplantation in Iran and Other Countries

ESRD patients in each country have two legal methods for receiving new kidneys. One is from the waiting list and the second is from a friend or relative with a match is tissue as well as blood. In the United States, due to the region, blood groups, and other factors, the average time on the waiting list ranges from three to 10 years (11). In the 1990s, by careful attention to the socioeconomic, cultural, and religious background in Iran, a controlled renal transplantation program was adopted. According to the law of organ transplants from the brain-dead and the cadaver, enacted in 2000, (12) source of kidney donation in Iran include:

(1) Living related kidney donation (LRD).

(2) Cadaveric kidney donation.

(3) Living Unrelated kidney donation (LURD).

Due to the long-waiting list of patients seeking organ transplant, the Iranian kidney transplant model has been at the center of attention (13). Iran has the shortest waiting list for kidney transplants in the world, while the United States as well as European countries have a very long waiting list (14).

According to the US Annual Data Report 2017, there were approximately 97000 patients registered in the waiting list; of these, 60% were eligible for a transplant if a kidney was offered to them (15). Patients would remain on the waiting list for eight to 12 years, which has caused more than 4000 kidney patients in the United States to die before they even got a chance to receive a kidney (16). Based on a recent study, by 2030 the number of people receiving RRT around the world is predicted to increase to 5.4 million. Most of this rise will be in the developing countries of Asia and Africa (16).

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This was a narrative study to present the Iranian model of a kidney transplant, which was performed to review publications before Jan 2018; PubMed, Scopus, Elsevier, Ovid, Google Scholar, and Iranian database include SID, Irandoc, manual search, and reference checking were used.

2.2. Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

All publications such as systematic reviews, qualitative, quantitative, books, reports, and the thesis that was implemented in Iran were accepted. According to the above criteria, two researchers independently reviewed titles and full-text copies of retrieved articles.

2.3. Critical Appraisal

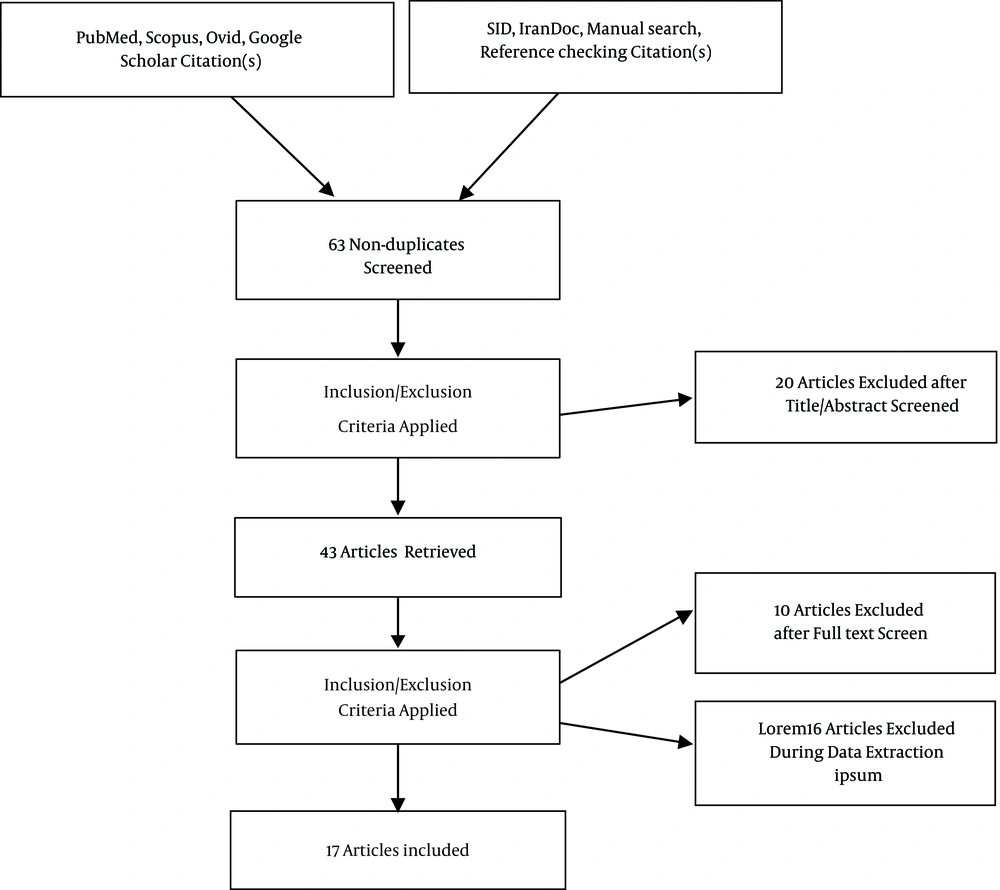

The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) was used for assessing the quality of the publications on each study. Similarly, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist were used for assessing systematic reviews (Figure 1).

3. Results

Overall, 61 publications were retrieved and screened. After exclusion of unsuitable and duplicate articles, 17 publications were included in this review. The Iranian model of kidney transplantation is an unrivaled example and has been distinctly questionable both inside and outside of Iran, particularly as the commercial relationship between donors and recipients.

In this section, the opinions and studies that were published by Iranian and international scientists over the past two decades have been reviewed, and the challenges, weaknesses and strengths, advantages and disadvantages of the Iranian kidney transplant model have been extracted (Table 2).

| The Strengths of the Iranian Model | The Weakness of the Iranian Model |

|---|---|

| Creating a legal structure for enforceable donor-recipient contracts | Inadequate public awareness about the concept of Brain Death and deceased organ donation |

| Existence a licensed non-governmental organization to provide free assistance to both recipients and donors | Socio-cultural factors, respect to dead that in many cases prevent transplantation |

| Increasing the number of renal transplants performed and decreasing the renal transplant waiting | Need for renewal and update existing laws, regulations, and guidelines |

| Providing guidelines to help to ensure informed consent for donors. | Lack of a mechanism for encouraging Brain Death patients’ families for organ donation |

| Rich and poor patients are equally transplanted | Lack of well-trained and motivated staff and dialysis machines in many states |

| Transplantations only were done at the university, and governmental hospitals by qualified transplant teams | High-cost immunosuppressive drugs and antibodies used for the treatment of rejection |

| There is no matchmaker or broker | The absence of a well-defined renal registry system |

| There is no financial benefit and money transactions for transplant team | The absence of a comprehensive network organ bank to generate the data for policy making (most estimates based on local information and the number of dialysis units) |

| Successful kidney transplantation improves both patients' survival and quality of life | The absence of lifelong health insurance and follow-up for the donors and support by the media in creating a more positive social image for them |

| Kidney transplantation is associated with markedly decreasing the cost of healthcare for the society and government | The incoherent growth of financial incentives with the inflation rate |

The Strengths and Weakness of the Iranian Model

Over the past 20 years, the issue of kidney transplantation in Iran and the Iranian model of transplantation have been discussed among Iranian and international scientists.

The adversaries and advocates of this model have declared their opinions and concerns in different articles, and sometimes, the political point of view of the authors has influenced their moral judgments and conclusions. On the contrary, the advocates of this model find it a way to help ESRD patients who can escape their renal disease and make a better life with their kidney transplants (17). They believe that the number of renal transplants performed substantially increased such that the kidney transplant waiting list was completely eliminated (17). In addition, it was explained that the Iranian model, a regulated transplant program supported by the authorities for living unrelated donors (LURD), was initiated for solving the problem of organ shortage (10). Other researchers demonstrated that the expense of kidney transplantation in Iran is low and the government pays for all the costs. These, along with the full coverage of health insurance, make kidney transplantation available for every patient, in any status, without financial concerns. It is anticipated that a greater number of transplantation applicants, with a low socioeconomic status will select transplantation (18). In addition, the current Iranian model has enabled most of the Iranian kidney transplant candidates, irrespective of socioeconomic class, to have access to kidney transplantation.

Simforoosh et al. in a recent study entitled “Living Unrelated Versus Related Kidney Transplantation: A 25-Year Experience with 3716 Cases” it was explained that between 1984 and 2015, patient survival and graft survival improved significantly, and was similar in LURDs compared with LRDs. Therefore, transplants from LURDs may be recommended as adequate management for patients with end-stage renal disease (19).

In summary, having a lawful structure and a non-governmental community in the relationship between donors and recipients, supporting health centers and patients financially by government and charity funds during the transplantation process, as well as decrease the waiting list are the main strengths of the Iranian model (Table 3).

| Author | Year | Study | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zargooshi (20) | 2001 | Iranian kidney donor motivations and relations with recipients | - The donor-recipient relationship in Iran is pathological with no similarity to the emotionally related category of transplantation. - Opinion of kidney donors should be regarded as the final arbiter. |

| 2 | Ghods et al. (17) | 2006 | Iranian model of paid and regulated living-unrelated kidney donation | - Increase the number of renal transplants performed. - Completely elimination the renal transplant waiting list. |

| 3 | Malakoutian et al. (21) | 2007 | Socioeconomic status of Iranian living unrelated kidney donors a multicenter study | - There is no middle man or broker introducing donors to recipients. - The transplantation team knows nothing about money transactions between recipient and donor. - Most donors were satisfied with the donation. - Establishment a government-regulated program for social support of donors, such as lifelong health insurance may be a compensation for donors. |

| 4 | Noorbala et al. (18) | 2007 | Renal transplantation in Iran over the past two decades: A trend analysis | - An increasing trend in the proportion of Living unrelated renal donation (LURD) transplants. - Significant growth in renal transplantation could also be due to the continuing rise in the number of LURD. |

| 5 | Einollahi (10) | 2010 | Kidney transplantation in Iran | - Successful kidney transplantation improves both patients' survival and quality of life. - kidney transplantation is associated with markedly decreasing the cost of healthcare for the society and government. |

| 6 | Mahdavi-Mazdeh (22) | 2012 | The Iranian model of living renal transplantation | - LURD did not prevent the development and progression of a brain death donation (BDD) program. - Operational weaknesses such as the lack of a registration system and long-term follow-up of the donors. |

| 7 | Ghahramani et al. (23) | 2012 | Paid donation a global view - stop organ trafficking now | - Increasing the number of kidney transplants and diminishing the waiting list. - Directed donation and lack of safeguards against mutual exploitation are major flaws. - The potential for exploitation compromises both recipients and donor selection, with poor follow-up and outcomes, and has negative psychological and ethical ramifications. - The absence of deceased donor programs puts major reliance on living donors. Transplant legislation should be implemented fully and protected from the rearguard action of exploitative transplant centers and other vested interests. |

| 8 | Beladi Mousavi et al. (24) | 2013 | Reasons for renal donation among living unrelated renal donors in Khuzestan Province, southwestern Iran | - Financial problems are the main motivation for living-unrelated kidney donation. - It is necessary to establish a social network for support of kidney transplant donors in Iran. |

| 9 | Koplin (25) | 2014 | The ambiguous lessons of the Iranian model of paid living kidney donation | - The prospect of organ markets raises a host of difficult questions:. - Philosophical (would they exploit sellers, or wrongfully commodify the human body?). - Empirical (would markets undermine living-related or deceased donation? Would sellers benefit from the opportunity to sell a kidney, or might they be left worse off in the long term?). |

| 10 | Pajouhi et al. (26) | 2014 | Paid living kidney transplantation in Iran rethinking the challenges | - A majority of donors lacked information about the future at the time of donation. - Pre-donation consultation program would help to make their decisions more logical and constant. - The method of paid donation in Iran is not exactly organ marketing, but it is a kind of rewarded gifting. - The money that the recipient is legally paid is not for buying an organ but for compensation of the donor’s medical and psychological costs. - There is no lifetime supportive mechanism for the donors. - The need for psychological support. |

| 11 | Khatami et al. (27) | 2015 | Quality and quantity of health evaluation and the follow-up of Iranian living donors. | - The donors are the neglected victims of renal transplantation and there is no plan for the safety and health of donors. - This model should be revised immediately, concerning both the medical and ethical issues. |

| 12 | Hamidian Jahromi et al. (14) | 2015 | A revised Iranian model of organ donation as an answer to organ shortage | - Created a legal structure for enforceable donor recipient contracts. - provided guidelines to help ensure informed consent for donors and they're next of kin. - Licensed nongovernmental organizations to provide free assistance to both recipients and donors in brokering transplant deals and applying for related government and charitable benefits. - Required that transplantations be performed at university hospitals and by qualified transplant teams. - Abolished the waiting list. |

| 13 | Aramesh (28) | 2016 | A closer look at the Iranian model of kidney transplantation | Advantages of Iranian model. - Elimination of the waiting list for kidney transplantation. - Elimination of kidney black market. - Disadvantages of Iranian model. - Commercialization and commodification. - Exploitation of the poor. - Stigmatization of donors. - Suppression of altruistic donation. |

| 14 | Ghahramani (29) | 2016 | Paid living donation and growth of deceased donor programs | The Iranian Model has serious flaws and is potentially inhibiting substantial growth in deceased donor organ transplants in Iran. - The Iranian Model is only partly regulated. - Direct monetary relationship between donor and recipient with no safeguards against mutual exploitation. |

| 15 | Soofi (30) | 2016 | Iranian kidney market in limbo a commentary “The ambiguous lessons of the Iranian model of paid living kidney donation” | - The Iranian healthcare system should tackle the organ shortage through increasing altruistic living and postmortem kidney donations. - Providing a space for conducting extensive and long-term follow-up studies on well-being, satisfaction and social integration of Iranian kidney vendors. |

| 16 | Simforoosh et al. (19) | 2016 | An updated Iranian model in kidney transplantation rewarded gifting a practical solution to kidney shortage crisis | Kidney Shortage is a global problem and is growing alarmingly. - Iran, with using LRD and LURD, has the shortest waiting list in the world due to the use of all potential sources for kidney transplantation. - Having regulated paid living donation does not inhibit deceased donor program growth. |

| 17 | Saidi Firouzabadi (31) | 2017 | Organ transplants in Iran and its challenges Development and cooperation, no competition | - Lack of a coherent system for transplantation. - Lack of an Update national laws. - Lack of a national bank of Donation data. - Lack of well-equipped centers in each province. - Lack of financial resources and insurance coverage. - Inadequate public awareness of deceased organ donation. |

Weaknesses and Strengths, Advantages and Disadvantages of the Iranian Kidney Model

On the other hand, advocates of paid living kidney donation frequently argued that the LURD program is characterized by several controversial items (e.g., confrontation of donor and recipient at the end of the evaluation procedure along with some financial interactions), which should be ethically reviewed. Operational weaknesses, such as the lack of a registration system and long-term follow-up of the donors, identified as the ‘Achilles heel of the model’ (29).

Ghahramani et al. in a study in 2012, explained that paying for donation leads to coercion and exploitation of the poor, and, in the end, produces more harm than good. Transplant legislation should be implemented completely and protected from the rearguard action of exploitative transplant centers and other vested interests (23). Beladi Mousavi et al. in a research in 2013, explained that although the health ministry pays for hospital admission, immunosuppressive drugs, and surgical procedures, it does not support long-term health insurance that can lead to dissatisfaction of donors. Accordingly, an Iranian social network is needed to support kidney transplant donors. They also mentioned that the first factor for kidney donation in that area was financial issues (24).

Evidence indicates that in its current form, the Iranian model is only partly regulated. The no anonymous directed donation fosters a direct monetary relationship between donor and recipient with any safeguards against mutual exploitation. Although it was designed to be an organ broker-free process with no transplant tourism, in 2014, individual brokers and 12 organ broker teams have arranged the transplantation of foreigners. Due to inflation, the relative value of governmental reward has decreased to a small portion of the total payment and the recipient assumes the major burden (29).

In an article Saidi Firouzabadi described the challenges in Iran's transplantation as follows (31):

- Lack of a coherent system for transplantation

- Lack of an update for national laws

- Lack of a national bank of donation data

- Lack of well-equipped centers in each province

- Lack of financial resources and insurance coverage

- Inadequate public awareness of deceased organ donation

As demonstrated in studies, the Iranian Transplantation model was initially designed to be a government-funded, strongly regulated, well-compensated paid donor renal transplantation program and Iran is working on adjusting its infrastructure deficiencies. The most important strength of this model includes the following factors:

(1) Implementing a legal formation for applicable donor-recipient agreements, providing guidelines to help to ensure informed consent for donors.

(2) Existence of an authorized NGO to provide support to both recipients and donors resulting in raising the number of kidney transplants and reducing the waiting list.

(3) Rich and poor patients are equally transplanted and transplantations were only done at the university and governmental hospitals by qualified transplant teams.

On other hand, challenges and barriers against kidney transplant programs in Iran can be seen at several factors:

(1) Inadequate public awareness about the concept of brain death and deceased organ donation

(2) Socio-cultural factors, respect to dead, that in many cases prevent transplantation

(3) Need for renewal and update existing laws, regulations, and guidelines

(4) Lack of a mechanism for encouraging brain death patients’ families for organ donation

(5) Lack of well-trained and motivated staff as well as dialysis machines in many states

(6) High-cost immunosuppressive drugs and antibodies used for the treatment of rejection

(7) The absence of a well-defined renal registry system and comprehensive network organ bank to generate the data for policy making (most estimates based on local information and the number of dialysis units)

(8) The absence of lifelong health insurance and follow-up for the donors and support by the media in creating a more positive social image for them

(9) The incoherent growth of financial incentives with the inflation rate

Some Suggestions for the Better Functioning of the Iranian Kidney Transplant Model

Kidney transplantation is an expensive method, however, investment in this area is less expensive and much effective than ESRD therapy. The transplant authorities in Iran should promote the Iranian model and work on strengthening the model to overcome some difficulties. The Iranian model encountered some challenges in solving its kidney shortage and implementing transplantation programs.

It is apparent that a transplant organ would never take the place of the main organ; therefore, preventing organ failure and its risk factors are the primary preference. Public education and promoting the organ endowment from brain death is the best method for providing organs.

Enhancing the outcomes of circulatory death donation could significantly reduce organ shortage. An investment in tissue engineering must be increased. The final solution for organ shortage and preventing the death of patients on the waiting list is the living unrelated renal donation (LURD). With some notable revisions and corrections, there is a chance that the Iranian Model could become an example for other countries.

The following suggestions will be useful for strengthening the Iranian transplantation model:

• Promotional awareness programs about causes, prevention, and management of kidney diseases

• Creating a more positive social image for donation through media (social media, newspapers, magazines, artists, athletes, and celebrities)

• Teaching organ transplantation concept in schools and universities as well as organized workshops and expert advice in hospitals and health centers

• Creating a comprehensive network organ bank as a nationwide organ sharing network that all organs should be utilized

• Creating a system for registering patients and collecting data that includes all major transplant centers by health authorities or Iranian Kidney Foundation

• Providing free lifelong health insurance, supportive fund, charity or joint-stock fund to the donors and their families, and prioritizing the donor’s family if they ever need to receive a kidney in the future

• Enforcement of existing laws, regulations, and guidelines, developing guidelines for evaluating donors and recipients, diagnostic and therapeutic methods before and after transplantation, and long-term follow-up of the recipient and the kidney donor

• Organize full health insurance coverage and supplemental or third-party insurance for all services (medicine, hospitalization, transplantation, laboratory tests, etc.)

• Improve transplant programs from the deceased donors and investment in tissue engineering and replacement of the kidney of the affected persons