1. Background

Immediate tracheal extubation during postoperative period has some economic reasons, and the recent tendency in cardiac surgery has been to extubate patients immediate after operation. Conversely, early extubation may not be in every respect benign and is not applicable in certain patients. An appropriate sensorium, normothermia, hemodynamic stability, adequate pulmonary function, adequate urine output, and minimal chest tube output are necessary for a safe and successful early extubation (1, 2). Additionally, safe and successful early extubation crucially need to effective pain management. Indeed, aggressive pain control during the immediate postoperative period after cardiac surgery decreases morbidity and mortality (3-5). Some previous studies have showed combination of general anesthesia (GA) and intrathecal anesthetic is an effective technique in cardiac surgery and provide hemodynamic stability and decrease cardiovascular response to surgical stimulation and time to extubation (6-8).

Bupivacaine, an amide type of local anesthetic, has high potency, slow onset (5–8 minutes) and long duration of action (1.5–2 hours). Intrathecal bupivacaine produces intense and prolonged analgesia and thus may be a useful adjunct in controlling postoperative pain and facilitating early extubation after cardiac surgery (8).

This prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study compared the use of intrathecal bupivacaine in combination with general anesthesia to general anesthesia alone in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery for its impact on early extubation and postoperative analgesic requirements.

2. Objectives

We compared the use of intrathecal bupivacaine in combination with general anesthesia to general anesthesia alone in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery for its impact on time to extubation.

3. Materials and Methods

After approval of the hospital ethics committee and collection of free informed consent, 34patients ASA class II, III (American Society of Anesthesiologist) undergoing CABG, Body Mass Index (BMI, 23-25) and ranging in age from 40 to 65 years were included.

Exclusion criteria were an ejection fraction below 40%, contraindications to neuraxial blockage, coagulopathy, use of low-weight heparin, warfarin, intrathecal morphine, or a platelet aggregation inhibitor other than aspirin, systemic or local infection, addiction, previous CABG surgery, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Congenital heart disease(CHD), combined procedures, and patients with a specific contraindication to the medication employed in this study. Preoperative aspirin use was not an exclusion criterion. Preoperative surgical risk was evaluated using Higgins Surgical Risk Scale for cardiac surgery, and patients were considered: (1) minimum risk, (2) low risk, (3) moderate, (4) high, (5) extreme risk12.

Sample size calculation:

N = 2(s/∆)2(zα + zβ)2

Α = 0.05

Power; 80

Zα = 1096

Zβ = 0.85

N = 2(201/2)2(1.96 + 0.85)2 = 17

To randomization we used sequential numbers, in this case the first number was given to the first patient and receive general anesthesia with prior administration of intrathecal bupivacaine 0.5% at a dosage of 20 mg (bupivacaine or case group n = 17) sequentially the next number was given to next patient and receive general anesthesia alone (control group n = 17). Both participants and study staff (site investigators and trial coordinating center staff) were masked to treatment allocation.

3.1. Anesthesia Procedures

On the day of the operation, the patients received 5 mg of midazolam IM 30 minutes before surgery for sedation. Patients were monitored by continuous (Electro Cardiograph) ECG and ST-analysis, pulse oximetry, and a noninvasive arterial line inserted in the right radial artery. Then all patients were prepared for intrathecal injection in sitting position.

In the bupivacaine group, 20 mg (4cc) intrathecal injection of bupivacaine was administered using a 27-gauge spinal needle in the L2 –L3 or L3-L4 space prior to induction of general anesthesia and immediately thereafter, patients were placed in the supine lithotomy position. If intrathecal puncture was not successful after two attempts, the patient was excluded from the study. In control group 1cc of lidocaine 2% subcutaneously was injected.

After pre-oxygenation, general anesthesia was induced using 3.0 mg/kg of sodium thiopental, 0.1 mg/ kg of midazolam, 15 μg /kg of fentanyl and 0.5mg/kg atracurium.

Mechanical ventilation was initiated using a Cícero ventilator (Dräger®, Germany) with a tidal volume of 8 ml kg-1, respiratory frequency of 12 ipm (inspiration per minute), oxygen inspired fraction of 0.6%, and 5 cm of H2O PEEP (Positive End Expiratory Pressure). A nasoesophageal thermometer, bladder catheter, and central venous catheter were inserted after anesthesia induction. When judged necessary by the attending anesthesiologist, a pulmonary artery catheter was placed in the right internal jugular vein. Immediately after intubation and after (Cardiopulmonary Bypass) CPB weaning, a lung expansion maneuver using an airway pressure of 30 cm H2O for 20 seconds was performed to revert any intraoperative lung collapse. During CPB, hypnosis was maintained with a propofol infusion aimed at maintaining a calculated plasma propofol concentration of 2.5 μg ml-1 and remifentanil 0.12-0.75 μg / kg.

In the intensive care unit (ICU), a patient-controlled analgesia pump (PCA) programmed for a 1 mg bolus of morphine with an administration interval locked at 5 minutes and free demand was installed. Dipyrone (30 mg kg-1) was administered if patients presented persistent pain despite the use of PCA. Tracheal extubation was performed when patients were fully awake and responsive to verbal commands, as well as when the peripheral oximetry was greater than 94%, spontaneous respiratory frequency was greater than 10, temperature was greater than 36° C, arterial PH > 7.3, urine output > 100cc /h, (Respiratory Rate) RR < 30, (Rapid Shallow breathing Index)' RSBI < 60-105, (Maximal Inspiratory pressure) MIP > -15—30 , Tidal Volume > 4-6 ml/Kg ,O2sat (saturation) > 92% , Mediastinal drain volume < 100cc/hand the patient was hemodynamically stable such that they were bleeding less than 100 ml/h. Patients whose tracheas were extubated within 8hours after operation were considered as early extubated patients and those were extubated after 8hours were defined as late extubated patients.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ilinois). The normal distribution of the collected data was confirmed by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Demographic and surgical data were compared between groups using the independent Student’s t-test and chi square. All data are presented as mean values ± standard deviation, or as otherwise described. The significance level was fixed at 0.05.

4. Results

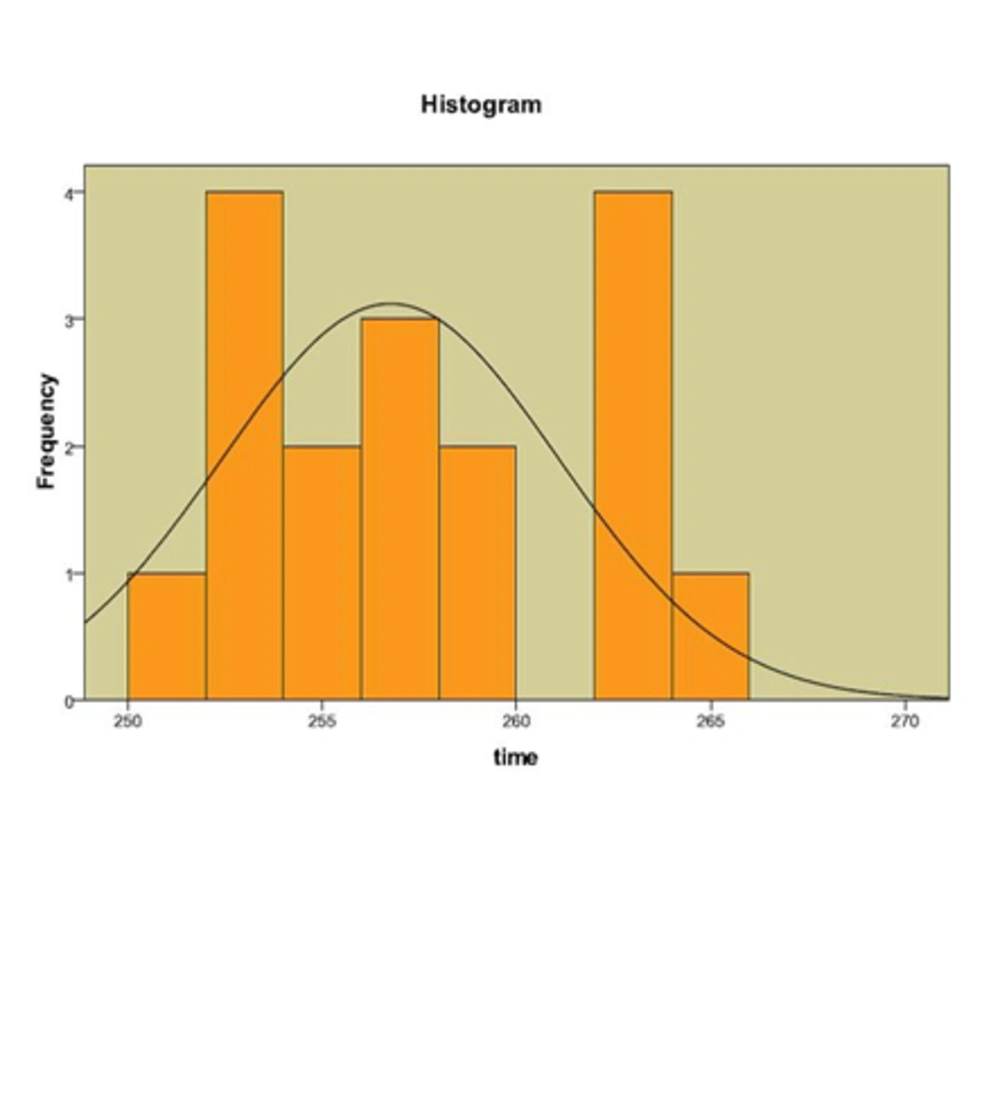

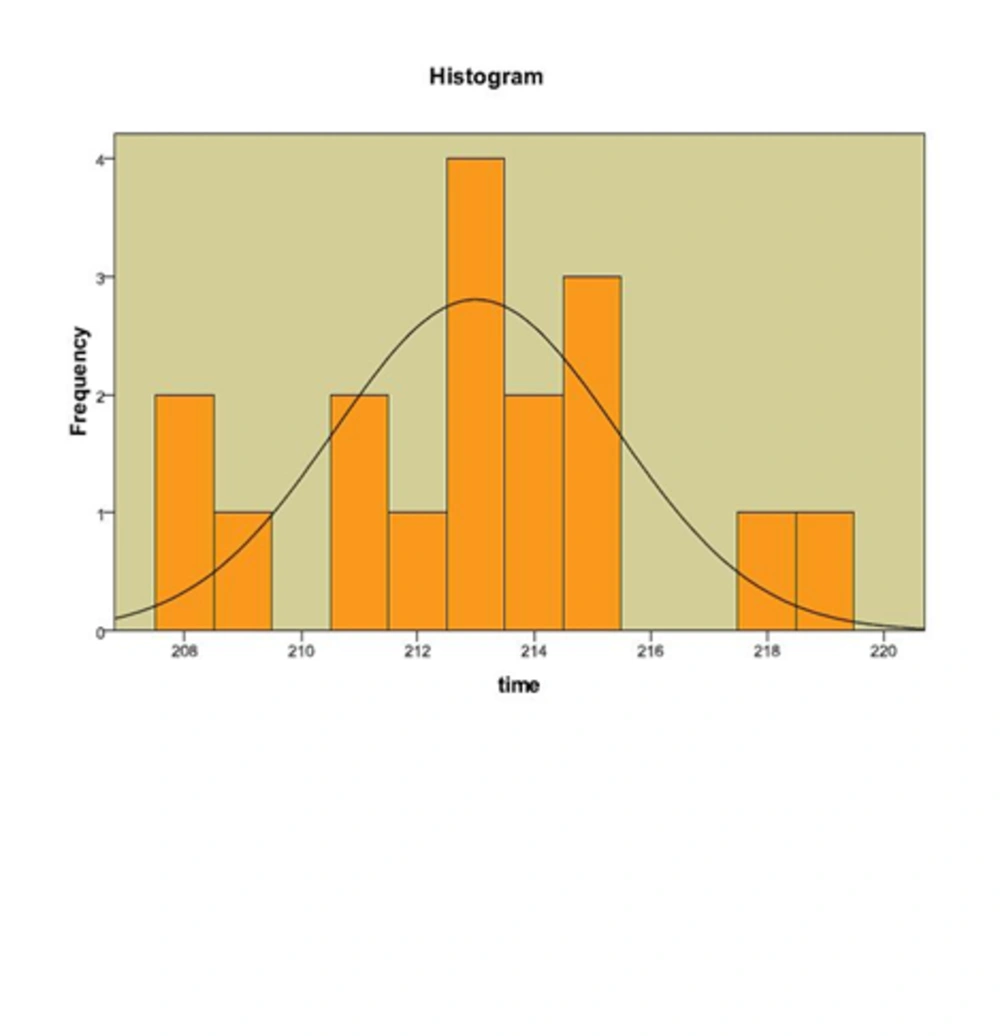

We evaluated 34 patients (male 18 (53%), female 16 (47%) mean age 53.2 ± 6.7 (ranged 40-65 years). Mean extubation time in bupivacaine group was 213.00 ± 3.06 minutes (3 hours and 33 minutes) and in control group was 257.12 ± 4.49 minutes (4 hours and 17 minutes).the difference between two groups was significant (P < 0.05).The results were detailed in Table 1&2 .All patients received morphine as analgesic (3.37 ± 0.12 in bupivacaine and 2.97 ± 0.12 mg/iv in control group) and difference between two groups was not significant (P > 0.05). Figures 1and 2.

4.1. Complications

In our survey we did not detect any intra and postoperative complications related to both anesthesia techniques in two groups.

| Bupivacaine | Control | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.32 ± 6.4 | 52.21 ± 7.0 | NS |

| Sex (M/F) | 9/8 | 9/8 | NS |

| BMI | 27.11 ± 3.10 | 26.80 ± 3.00 | NS |

| Operation time | 208.5 ± 2.44 | 260.00 ± 3.79 | 0.045 |

| Mean ± SD | Max | Min | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | ||||

| Bupivacaine | 213.00 ± 3.06 | 219 | 208 | 0.04 |

| Control | 257.12 ± 4.498 | 265 | 251 | 0.04 |

5. Discussion

Because of some economic reasons, recently anesthesiologists' trend in cardiac surgery has been to extubate the patients as soon as during the postoperative period (9, 10). However, early extubation can be related to some risks and is not proper in many patients (11, 12). Because of this and other related reasons when early extubation is planned, aggressive control of postoperative period is essential. In this case, combination of general anesthersia (GA) with a regional anesthetic seems to be suitable in (CABG) surgery.

In this prospective study, we indicated that intrathecal bupivacaine administration in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery, reduced time to extubation (from 257.12 ± 4.498 in GA group reduced to 213.00 ± 3.06 minutes in Bupivacaine plus GA group). And differences between case and control group was significant (P < 0.05).

In line with our findings Kowalewski et al. in a review study in 1994 on 18 CABG patients showed that combined GA with bupivacaine or morphine is an effective technique for CABG surgery (13). Moreover, other study by Chaney et al. Showed, intrathecal morphine is a useful adjunct in controlling postoperative pain in patients after CABG surgery, but, as opposed to our results this study indicated that the use of intrathecal morphine in CABG patients can delay early extubation of the trachea (8).

In this regard liu et al in other study on patients with coronary artery bypass surgery, indicated that intrathecal morphine plus GA reduce the risk of pulmonary complications (OR 0.41), time to tracheal extubation by 4.5 hours, and analog pain scores at rest and with activity (14).

In other review, Barrington in 2005 evaluated 100 patients and compared epidural anesthesia plus GA to general anesthesia alone and noted that regional anesthesia plus GA improved postoperative analgesia and was associated with a reduced time to tracheal extubation (15).

We did not detect any hemodynamic instability and other intra and postoperative complications related to both anesthesia techniques in two groups. But in general, the most severe complications that may be related to regional anesthesia for cardiac surgery are hypotension, respiratory depression, and epidural hematoma formation. Systemic arterial hypotension is an undesired effect of intrathecal and epidural local anesthetic blockade. In adults involved in coronary artery stenosis and myocardial ischemia, local anesthetic-caused blockade of cardiac sympathetic nerve activation, moderates angina and improves coronary blood flow and ventricular function, but, local anesthetic blockade to upper thoracic dermatomes leading to hypotension and decreases the coronary artery perfusion (16, 17).

The main limitation of our study was the relatively small sample size and further investigations are recommended with larger series to validate the findings reported here.

In conclusion, regarding mentioned above studies and our results in current survey, intrathecal bupivacaine offers promise as a useful adjunct in reducing postoperative time to extubation in cardiac surgery patients. Moreover, the technique has been applied to a large number of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery in many studies and appears to be safe.