1. Background

Chronic lumbar pain with unknown causes appearing and persisting after surgical intervention is specified as Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (FBSS). This condition involves complicated pathophysiology and multiple factors that can lead to chronic pain. Discectomy, laminectomy, or other spinal surgeries can result in spinal instability, spinal stenosis, and epidural fibrosis, which may aggravate existing pain and symptoms or create new ones after surgery (1).

Due to the multifactorial causes of pain and its relief, investigators have focused on factors such as age, gender, and underlying diseases (2). Research has shown that pain is more intense in certain patients because of hormonal, physiological, anatomical, and psychological factors (3). Painful conditions, restricted functional activity, and poor quality of life in patients with underlying diseases like diabetes mellitus (DM) result from damage to the peripheral nervous system, leading to reduced microcirculation and tissue damage (4). Current approaches for chronic pain management include both invasive and non-invasive methods. Before considering any invasive procedures, pharmacological treatments (5, 6) and conservative treatments, such as physical therapy modalities and rehabilitation (7)), should be regarded.

Researchers have evaluated laser therapy (LT) as an effective conservative treatment for neurodegenerative diseases. It has been found that LT reduces inflammation in damaged tissues by improving local microcirculation and inhibiting the release of inflammatory cytokines, which may prevent hyperalgesia and provide analgesia (8-10). Furthermore, the improvement of collagen synthesis, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis leads to tissue repair (11, 12).

2. Objectives

In our previous study, we assessed the impact of age on the efficiency of laser therapy in patients with FBSS (13). Building on that research, this study investigates the relationship between DM and the therapeutic effects of laser therapy on patients experiencing pain and disability after lumbar surgery, focusing on improving their quality of life and reducing pain.

3. Methods

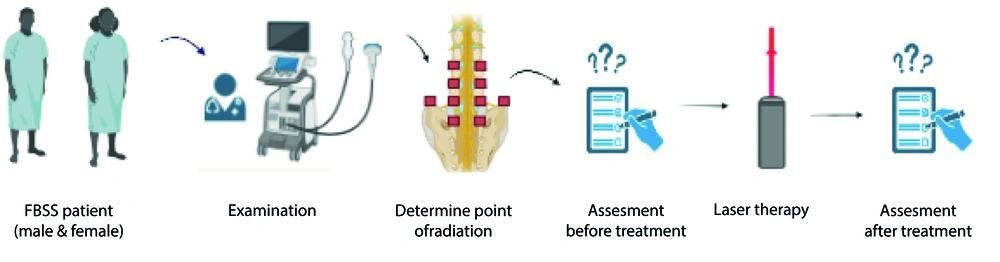

This investigation was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.NI.REC.1399.016). The method of the study is depicted in Figure 1 as a graphical abstract.

3.1. Case Selection

Forty-eight individuals (22 diabetic patients and 26 non-diabetic patients) who experienced back or leg pain and underwent back surgery were included in the study. All participants were aged 30 to 75 years and had undergone lumbar surgery more than three months prior. Individuals with apparent skin diseases in the area of laser irradiation, allergic reactions, pregnancy, alcoholism, unmanaged psychiatric diseases, sustained neurologic deficits, a history of malignancy, or abnormal BMI were excluded from the study.

3.2. Treatment

A sonography device (convex transducer, Samsung Inc.) with frequencies of 4 - 8 MHz was used to determine irradiation points. Bilaterally, sacroiliac joints, facet joints from L2 - L3 to L5 - S1, and the supracrestal iliac zones were determined for Cluneal nerves.

Laser calibration was usually carried out to illuminate the target points before each session of laser therapy. In this study, an infrared diode laser (WLINT device IEC 60825-1:2014) with continuous mode and radiation was utilized. Laser therapy was administered every other day for three weeks. The dosimetry parameters of the laser therapy procedure are shown in Table 1.

| Parameters | Quantity |

|---|---|

| Wavelength (nm) | 808 |

| Output power (mw) | 500 |

| Spot size (cm2) | 0.25 |

| Intensity (w/cm2) | 2 |

| Dose (J/cm2) | 20 |

| Time of radiation (s) | 10 |

The Parameters of the Laser Beam

3.3. Analysis

3.3.1. Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)

The Numeric Rating Scale was used to assess pain severity. This pain assessment tool is typically employed to evaluate pain intensity at a given moment on a 0 - 10 scale, with 0 indicating "no pain" and 10 representing "the worst pain possible" (14).

3.3.2. Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)

To assess functional disability, the ODI questionnaire was utilized to measure the patient's sustained functional disability. This questionnaire includes information about pain intensity, lifting, walking, sleeping, sitting, standing, sex life, personal care, traveling, and social life, regarding the effects of back or leg pain and the patient’s ability to manage daily life activities (15).

Both ODI and NRS were recorded before treatment, immediately after therapeutic sessions, and six months after treatment. The same medical practitioner evaluated all patients to ensure consistency.

3.3.3. Statistical Analysis

For data analysis, SPSS software (Version 25.0, NY: IBM Corp) was used. The repeated measurement test was utilized to compare the trends in ODI and NRS (continuous variables) at various time points.

4. Results

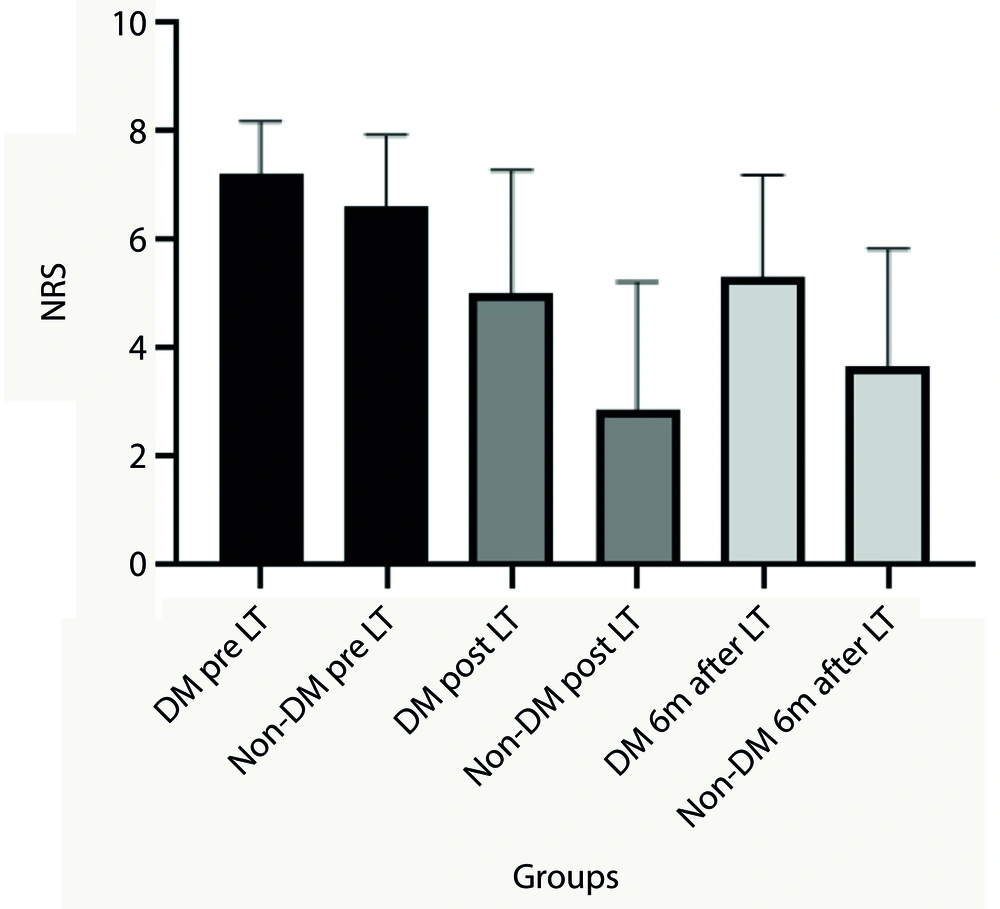

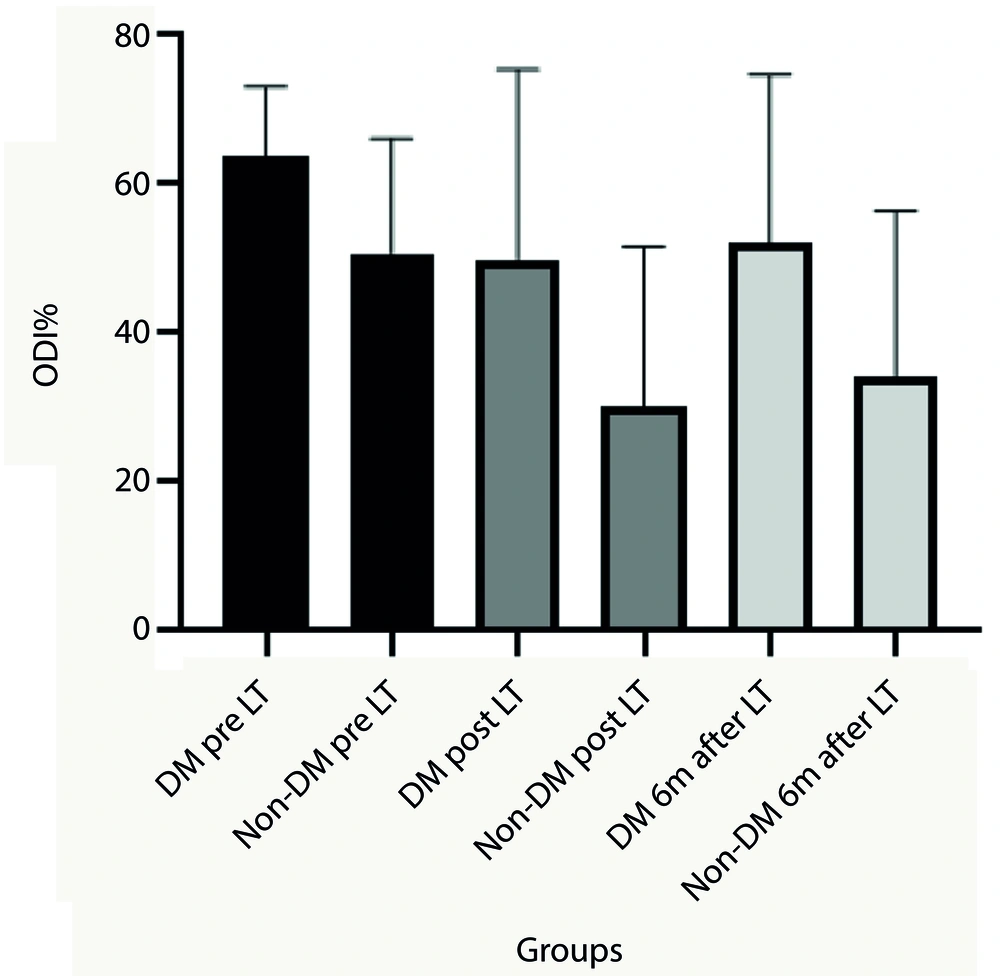

Collected data were shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Oswestry Disability Index and NRS scores were recorded after the laser therapy sessions and six months later, but not compared to pre-therapeutic values. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences between the collected data before and after therapeutic sessions, as well as during the six-month follow-up period, in the non-diabetic patient group (P < 0.001).

More specifically, changes in NRS scores pre- and post-laser therapy and six months after treatment were significant in diabetic patients (P < 0.05), while changes in ODI scores were not significant. Additionally, there were significant differences in the trend of ODI and NRS post-treatment values and six months after treatment between diabetic and non-diabetic patients (P < 0.05). Diabetic patients experienced fewer therapeutic effects during and after the laser therapy sessions (Figures 2 and 3).

The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) mean values before and after treatment sessions and 6 months after treatment. Analysis represent significant differences between diabetic patients and non-diabetic patients post laser therapy and 6 months after laser therapy (P < 0.05). (LT (Laser Therapy), DM (diabetes mellitus patients) and Non-DM (Non-diabetes mellitus patients)).

The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) mean values before and after treatment sessions and 6 months after treatment. Analysis represent significant differences between diabetic patients and non-diabetic patients post laser therapy and 6 months after laser therapy (P < 0.05). (LT (laser therapy), DM (diabetes mellitus patients) and non-DM (non-diabetes mellitus patients)).

5. Discussion

Chronic pain after surgery occurs when a surgical process leads to undesired problems or damage to intact tissues. The pathophysiology of chronic back or leg pain is complex and includes common causes such as disc herniation and degeneration (16), sacroiliac and facet joint dysfunction (17, 18), cluneal nerve damage (19, 20), and direct damage to muscular tissue (21).

Laser therapy has been utilized for treating various disorders due to its ability to heal damaged tissues, regulate cellular function, restore tissue homeostasis, and reduce acute and chronic pain (arthritis, tendinitis, back pain, fibromyalgia, etc.), thereby enhancing functional movement in patients (22-24). Laser therapy induces changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential caused by photochemical alterations related to specific photo-acceptor chromophores, which accelerates electron transport and ATP and Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) synthesis (25). Literature confirms that antioxidants can restore neurons by restoring mitochondrial activity and controlling reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Additionally, lasers can increase antioxidants like glutathione and superoxide dismutase (SOD) and improve nerve function (26, 27). The decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, IL-8) inhibits the progression of inflammation, while NF-κB is downregulated and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10) are upregulated (28, 29). Due to LT's ability to promote regeneration and reduce degeneration, its effects can last longer than the treatment sessions (30).

In this context, some diabetic patients experience neuropathic pain along with back or leg pain. Even though laser therapy alleviates neuropathic pain (31), diabetic patients reported more intense pain following treatment compared to non-diabetic patients. Our findings indicated that laser therapy had fewer therapeutic effects for diabetic patients. Therefore, it is necessary to recommend additional medications and other approaches to achieve a better quality of life.

We acknowledge some limitations of our study, including non-homogeneous demographic features and the inability to control the patients’ daily activities. More randomized clinical trials with larger sample sizes are needed for more confident outcomes.

5.1. Conclusions

For chronic pain after lumbar surgery, conservative treatment like low-power laser therapy can be advantageous and safe, but individuals with underlying diseases may experience less benefit.