1. Background

A sedentary lifestyle is one of the leading risk factors for mortality worldwide; inactive people are more prone to disability and mortality (1). Lack of physical exercise is considered as the major cause of obesity and metabolic diseases, such as chronic inflammation, type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, and cancer (2-4). Exercise is a non-prescriptive therapeutic strategy to prevent or treat various diseases. It is an important factor in reducing the size and lipid adipocyte content and enhancing mitochondrial proteins, such as Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator-1-alpha (PGC1α) in adipose tissue, which is a mitochondrial biogenic stimulant (5).

Recent studies have shown that skeletal muscle has endocrine function as it secretes a hormone called myokine. This highlights the role of skeletal muscle as the main source of hormone secretion from exercise (6). The ability to produce and release chemokines is primarily due to metabolic changes caused by exercise-induced muscle contractions, which increase the release of several myocytes that are able to interact with adipose tissue such as IL-6, IL-15, and irisin (7). Irisin is a myokine that is secreted a lot during exercise. It is responsible for activating non-leukemia thermogenesis in beige and brown fat tissues by stimulating the expression of the uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) (8). Irisin is composed of proteolytic decomposition of a membrane protein called Fibronectin Type Iii Domain Containing 5 (FNDC5) in skeletal muscle. On the other hand, the expression of FNDC5 gene increases due to the increased expression of PGC1α gene during exercise (9).

After discovering the irisin as a sports hormone in mice and humans, several studies examined the questions about the production and release of irisin during exercise. Although in some studies irisin is considered a target for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders (10, 11), further studies are required on the mechanism of exercise's effects on iris production and release and its role in regulating metabolism and body composition. Moreover, some studies have shown a significant increase in irisin concentration after exercise (12, 13). The chronic effects of exercise on PGC1α, irisin, and browning of skinfold adipose tissue in inactive men (40 to 65 years old) were investigated. The exercises consisted of 12 weeks (four sessions per week) combined moves (strength-resistance). After the exercises, the irisin levels did not change significantly, and the browning of skinfold fat did not occur (12). In another study, the effect of six weeks of whole-body vibration training on irisin levels was studied in healthy inactive women, and no significant change was reported (13).

2. Objectives

Regarding the study of irisin without exercise, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of eight weeks of high-intensity interval training (HIT) on irisin serum levels in overweight young men.

3. Methods

This was a quasi-experimental and applied study conducted in the Islamic Azad University of Bojnourd for a postgraduate dissertation with the code of 18221404952014. The statistical population of the study consisted of overweight young men in sports clubs of Bojnourd, among whom 20 young obese males between 25 and 35 years old were selected as the statistical samples. Then, they were randomly divided into control (n = 10) and experimental (n = 10) groups (Table 1). The number of subjects was obtained according to the studies (3). The entering criteria for the study included being healthy (without a background of any cardiovascular, kidney, lung, and diabetes), overweight and obesity (BMI between 25 to 35 kg.m-2), and taking no medicine for metabolic diseases. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects.

| Group | Age (y) | Height (m) | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 27.3 ± 7.4 | 176.2 ± 4.2 | 87.9 ± 8 |

| Control | 31.5 ± 2.95 | 178.1 ± 7.5 | 93.4 ± 14.1 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

Before the training sessions, the initial measurements, including weight, height, BMI, and maximum heart rate (MHR) of the subjects were measured. Additionally, the blood samples were taken from the subjects 24 hours before the beginning of the exercise, and while they were fasting at least 12 hours before the test. The exercises were then performed for eight weeks. Blood sampling was performed again 48 hours after the last training session.

The exercise protocol was the HIT exercises for eight weeks, three sessions per week, and each session for 45 to 60 minutes (sessions were held between 10 to 12 a.m.). The intense periodic exercise program included warming up with all kinds of stretching and flexible exercise for 10 minutes and then performing intense periodic movements with a 2-minute active break between each set. The exercise program was run from simple to difficult, considering the overload principle and increasing the workout intensity. The intensity of the periodic exercise pattern was as follows (14): 1st week: 3 sets of 4 minutes with 90% heart rate reserve (HRR) intensity with 2 minutes of active recovery; 2nd week: 4 sets of 4 minutes, 90% HRR with 2 minutes of active recovery; 3rd week: 5 sets of 4 minutes running at 90% HRR intensity with 2 minutes of active recovery; 4th week: 6 sets of 4 minutes running at 90% HRR and 2 minutes of active recovery; 5th week: 7 sets of 4 minutes running and 90% HRR intensity with 2 minutes of active recovery; 6th week: 8 sets of 4 minutes running with 90% HRR intensity with 2 minutes of active recovery; 7th week: 6 sets of 4 minutes with 90% HRR intensity with active 2-minute recovery; 8th week: 5 sets of 4 minutes with 90% HRR intensity with 2 minutes of active recovery.

The intensity of the exercises was controlled by a Finnish polar beater. The control group did not have any activity during the exercises.

Blood samples were taken 24 hours before the exercise and 48 hours after the training by a laboratory expert through the left arm of the subjects in a sitting position with a volume of 5 mL of blood. ELISA method and a special kit (Eastbiopharm) were used to test the blood. Finally, all the statistical data were tested according to the thesis hypotheses.

The limitations of the study incorporated the lack of control for individual differences and their impact on fitness adjustments from physical exercise, lack of complete control over the subjects’ physical activity, outside the research hours, lack of precise control of subjects’ nutrition during the training period, and lack of control of the subjects' motivation during the tests.

Shapiro-Wilk test statistical tests were used to evaluate the data distribution. After identifying the lack of normal data distribution, the Wilcoxon test was used to compare the pre-test and post-test results of the two experimental groups, and U-Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare the variables between the groups. SPSS V. 23 was used for data analysis, and the significance level was considered less than 0.05.

4. Results

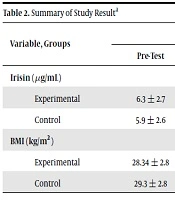

The research findings analysis showed that in the experimental group, the BMI values were decreased significantly (P = 0.023), and the irisin value was increased significant (P = 0.005). Also, the difference between BMI (P = 0.049) and irisin (P = 0.031) was significant between experimental and control groups (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 2).

| Variable, Groups | Steps | Wilcoxon Results | UMW Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Z | P Value | Z | P Value | |

| Irisin (μg/mL) | ||||||

| Experimental | 6.3 ± 2.7 | 7.2 ± 2.5 | 2.8 | 0.005 | 2.16 | 0.031 |

| Control | 5.9 ± 2.6 | 5.02 ± 1.66 | -0.95 | 0.34 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Experimental | 28.34 ± 2.8 | 27.15 ± 1.7 | 2.7 | 0.023 | -2.11 | 0.049 |

| Control | 29.3 ± 2.8 | 29.2 ± 2.7 | 1.45 | 0.18 | ||

Abbreviation: UMW, U-Mann-Whitney test.

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

5. Discussion

The results showed that there was a significant increase in the amount of irisin in the experimental group after HIT training and a decrease in BMI. This finding was consistent with the findings of Kang et al., Amri et al., Martinez Munoz et al., Zhang et al. and Huh et al. (15-19). Kang et al. reported that swimming increases blood irisin and bone PGC-1α and FNDC5 levels (15). Amri et al. showed that 10 weeks HIT led to elevation of irisin in Wistar rats (16). Martinez Munoz et al. reported direct association between muscle strength and irisin levels in normal-weight and overweight young women (17). Zhang et al. reported that electroacupuncture combined with treadmill exercise increased expression of PGC-1α, FNDC5 and AMPK in skeletal muscle of rats (18). In a study by Huh et al., circulating irisin increased immediately after HIIE, CME, and RE and declined the next hour (19).

In the subjects, high irisin was related to a decrease in BMI, which could indicate a reduction in the fat percentage due to the increase in irisin. The irisin in the adipose tissue stimulates the expression of the UCP1 gene by increasing the non-vibrated pyrogenic of the fatty acid, which can affect the conversion of white to brown adipose tissue and reduce fat percentage and subsequently weight loss. This is consistent with the findings of the present study (8). Physical exercises increase cyclic adenosine mono phosphate (cAMP) by stimulating beta-adrenergic receptors 2 by catecholamines and subsequent stimulation of the protein bound to the cAMP response of camp response element-binding protein (CREB), which stimulates the expression of the PGC1α gene. It also increases the amount of FNDC5 in the muscle membrane, resulting in high levels of irisin. Also, the activation of AMPK leads to phosphorylation of PGC1α, a stimulant of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), and stimulating FNDC5 and irisin to stimulate energy and brownness of white fat (18).

Generally, the findings showed that the eight-week of HIT exercise was effective in increasing irisin and reducing BMI in overweight young men. It may be a suitable stimulant through the conversion of white to brown adipose tissue for lipolysis and a reduction in the fat percentage and weight.