1. Context

Marriage is often the first emotional-legal obligation that individuals accept, and commitment is one of its most essential and sensitive aspects (1). Commitment is the cornerstone of marriage, encouraging the couple to have a long-term view of their shared life to put effort into maintaining and strengthening their union and trust (2), which can be damaged over time due to various problems such as extramarital infidelity (EMI) (3).

It is estimated that the probability of infidelity is 20% during the life of married people (4). Extramarital infidelity includes relationships that are outside the realm of marriage, in which an illegal or romantic relationship is established with someone other than one’s spouse, often to satisfy one’s emotional or sexual needs (5). Some studies have shown that those who initially experienced EMI were significantly more likely to separate or divorce in the next 2 years than those who did not (6). It was more common among men (7), but surprisingly, in recent research, men and women have had an equal prevalence of EMI (8).

Extramarital infidelity would appear a private phenomenon at first glance, but its detrimental consequences for the family foundation, the upbringing of children, and the cohesion of community health and safety lead to serious social harm (9). This phenomenon can lead to the loss of identity, self-worth, self-confidence, depression, guilt, frustration, doubt, and violence towards the children and the spouse. Besides, loss of social status and honor among family and friends, divorce, and contraction of sexually transmitted diseases (especially acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and hepatitis) are among its harmful effects (10-16).

Extramarital infidelity is increasing in general and in various social groups. The increase in the number of articles on this subject in newspapers, contacts with counselors, clients visiting counseling centers, and the rate of divorce indicate its social burden. The victims of 30% of familial homicides are women killed by their husbands due to fidelity-related issues. Furthermore, 40% of homicides with a woman killing her spouse are planned and implemented with the assistance of the woman’s lover (7, 17, 18). However, there is a wide research gap in the intervention, education, counseling, support, and rehabilitation of EMI.

There is a need to address the direct and indirect ways in which culture and religion affect these behaviors in both personal and social life. This study aimed to review the literature about the effectiveness of spiritual counseling enhanced with cognitive-behavioral techniques in addressing this social phenomenon.

2. Literature Review and Article Selection

This study involved a simple review. Descriptive, analytical, and intervention articles indexed in SID, Noormags, Scopus, Iranmedex, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar were searched. We also searched the reference lists of relevant articles and grey literature and consulted experts. All the search results were exported to EndNote (version X7, for Windows, Thomson Reuters, Toronto, Canada), where duplicates were removed.

All the reviewers convened to discuss discrepancies between reviewers. Following this, full-text versions of studies that were deemed to be potentially eligible for the review were obtained, and two reviewers independently evaluated each paper. In cases of doubt, the full text was subjected to adjudication by a third researcher on the team (the process involves having a third researcher on the team to make a final decision).

The keywords used to search for related articles since 1996 were “spiritual,” “spiritual health,” “religion,” “therapies,” “cognitive behavior,” “cognitive behavior,” “technique,” “therapy,” “extramarital relationship,” “extramarital sex behavior,” “infidelity,” “adultery,” “unfaithfulness,” “marital infidelity and women.”

We focused on studies that employed extramarital relationships among women, including only studies on heterosexual married couples, as well as studies on the use of spirituality/religion and CBT as coping techniques in EMI therapy.

The inclusion criteria for the articles were descriptive, analytical, and intervention articles from 1996 to date in Persian or English, available in full text, and providing information related to the searched keywords. The exclusion criteria were articles with no full text or in which the implementation was not well-defined. After excluding the articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria or met the exclusion criteria, the full text of all eligible articles was prepared and discussed in this review.

3. Findings

3.1. The Nature of Extramarital Infidelity in Women

Based on some studies, there are three types of EMI: Emotional infidelity (friendly, romance, and teasing), sexual infidelity (sex, intimate touching, and kissing), or both (19, 20). Women usually determine their EMI based on their initial relationship by explaining their dissatisfaction with their husbands. In contrast, men usually establish their relationship independently of their married life. Women are more intent on emotional infidelity or an emotional attachment outside of marriage than sexual infidelity. However, women are judged and punished more severely and suffer more from disclosing this type of relationship. It can be one of the main reasons for the higher prevalence of EMI among men (21, 22).

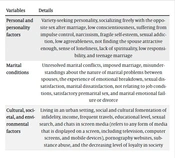

There are 3 main factors leading to EMI (Table 1) (23-29).

| Variables | Details |

|---|---|

| Personal and personality factors | Variety-seeking personality, socializing freely with the opposite sex after marriage, low conscientiousness, suffering from impulse control, narcissism, fragile self-esteem, sexual addiction, low agreeableness, not finding the spouse attractive enough, sense of loneliness, lack of spirituality, low responsibility, and teenage marriage |

| Marital conditions | Unresolved marital conflicts, imposed marriage, misunderstandings about the nature of marital problems between spouses, the experience of emotional breakdown, sexual dissatisfaction, marital dissatisfaction, not relating to job conditions, satisfactory premarital sex, and marital emotional failure or divorce |

| Cultural, societal, and environmental factors | Living in an urban setting, social and cultural fomentation of infidelity, income, frequent travels, educational level, sexual search, and chats in screen media (refers to any form of media that is displayed on a screen, including television, computer screens, and mobile devices), pornography websites, substance abuse, and the decreasing level of loyalty in society |

Social and cultural fomentation refers to the ways in which social and cultural factors contribute to the acceptance or promotion of infidelity within a society or group. This can include things like social norms and values, attitudes towards relationships and sexuality, and the role that media and popular culture play in shaping these attitudes. It’s important to note that while infidelity is a common issue in all cultures and societies, the ways in which it is perceived and treated can vary greatly.

3.2. Definition of Spirituality and Religion in The Mental Health and Human Behavior Literature

Spiritual health consists of religious and existential health. Religious health represents one’s relationship with God or an unlimited source of infinite power. It is one’s relationship with others, environment, oneself, and Divine existence that creates the capacity to integrate its dimensions with different life choices (25, 30). It is a fundamental human dimension whose gradual growth begins in childhood. It can be positively or negatively affected or interrupted, and it can be vulnerable and become traumatized (31).

Lack of spirituality leads to spiritual distress, loneliness, depression, and loss of meaning and self-esteem (32). Personal communications are hampered by uncertainty about the future, especially when adaptation mechanisms are inadequate. Spiritual turmoil can destroy positive motivation. Being spiritually upset and anxious may induce greater suffering caused by low self-esteem, loneliness, weakness, anger, and hopelessness (33). In addition, a lack of meaning in life produces an inadequate understanding of the philosophy of life and a feeling of insecurity (34, 35). People with more spiritual health feel less loneliness and are more socially skilled, self-confident, and religiously committed (36).

3.3. Spirituality as a Therapy

In the last few decades, more mental health therapists have focused on spiritual (biological-psychological-social) health to increase well-being (37). In fact, spirituality is an inseparable dimension of human existence and should be taken seriously along with other mental frameworks. Mental health trauma leads to spiritual trauma. Considering the intertwining nature of religiosity, spirituality, and mental health and their interactions, special attention should be given to spiritual counseling (38).

There is a positive relationship between spirituality, religion, and mental and physical health (39). Many therapists have identified faith and spirituality as important sources of health and well-being and have tried to initiate conversations about patients’ spirituality (37, 40). Furthermore, if they enhance their spiritual and religious healing skills, they will gain the trust of their clients and empathize with them more easily (41). Neglect of the religious and spiritual beliefs of clients by therapists diminishes the effectiveness of counseling and therapy and often results in the untimely termination of treatment (42).

Religious beliefs and activities, such as praying, attending religious ceremonies, and communicating with God, have a positive impact on one’s health, mental well-being (43), and quality of life (44). There is a significant relationship between religiosity, power of adaptation, and a sense of meaning (45, 46).

Through spiritual therapy, clients affirm their identity and seek God’s guidance to help them evaluate and cope with their life problems, heal, grow, improve, evaluate, identify, and modify their ineffective and irrational beliefs, assess their existential doubts, and make efforts to resolve them. Forgiving others and making amends for one’s own past mistakes are positive outcomes of religiosity and spirituality that lead to freedom from suffering. (41). Incorporating one’s beliefs in this way positively modifies cognitive assessments, enabling coping processes to evaluate negative events in a transcendental way and create a stronger sense of internal and external control (47). Therefore, they will be less affected by difficult conditions and maintain their mental health (48).

The International Human Rights Network has pointed out that there is universal interest in spiritual and religious issues. Moreover, there is a positive relationship between spirituality, religion, and mental and physical health. Furthermore, due to the accumulation of spirituality and mental health research, the American Psychological Association (APA) has devoted a separate handbook to spiritual and religious research to motivate more coherence and integration in this field. The International Human Rights Network has pointed out that there is a universal interest in spiritual and religious issues (39).

3.4. Assessing Spirituality in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Assessing spirituality in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) involves 4 stages: Orientation, functional assessment, collaboration, and monitoring. These stages aim to gather information about the client’s religious and spiritual beliefs, explore the connection between religion/spirituality and their problems, integrate CBT techniques with their spiritual framework, and evaluate the impact of incorporating religion and spirituality into therapy. By incorporating religion and spirituality into CBT, therapists can enhance clients’ motivation and engagement, make CBT concepts more accessible, and potentially improve treatment outcomes. This approach also allows therapists to address various issues such as behavioral activation, exposure therapy, intolerance of uncertainty, fear of negative evaluations, and perfectionism. By considering the spiritual aspects of clients’ lives, therapists can provide a more comprehensive and holistic approach to treatment (49, 50).

3.5. Spirituality Integrated into The Cognitive-Behavioral Approach

The integration of religion and spirituality with CBT can enhance clients’ motivation and engagement in therapy, leading to better treatment outcomes (51). By structuring therapy according to religious/spiritual directives and using religious/spiritual texts, clients can understand CBT concepts more easily. Additionally, incorporating spiritual elements can help clients participate in social, enjoyable, and nurturing activities to enhance their emotional capacities. Techniques such as cognitive restructuring, yoga, coping statements, spiritual and religious stories, guided meditation, mindfulness, gratitude exercises, and forgiveness exercises can be used to promote mental focus, calmness, physical comfort, and spiritual growth. These techniques aim to provide a holistic approach that addresses both psychological and spiritual well-being (49, 50).

Numerous studies have shown that cognitive therapies based on spirituality are as important and effective as conventional cognitive therapies (37, 52). Individual spiritual and psychological interventions for female sexual assault victims have demonstrated that spirituality-based interventions are at least as effective as standard nonreligious approaches to treatment for patients who believe in them (53). Integrative religious psychotherapy was more effective in reducing depression and had a more lasting effect on drug treatment over the 6-month follow-up (31). Cognitive-behavioral group therapy with a religious orientation can be effective in marital satisfaction as well (54, 55).

3.6. The Role of Spirituality as A Deterrent to Extramarital Infidelity

Almost all religions believe that sex outside marriage is abusive. People who tend to EMI typically have some specific personality traits. With weak faith and ethical restraints, not only do these people fail to adapt to the framework of marital commitment, they try to avoid it in various ways (56). Spirituality has an important role in improving marital commitment, enhancing the quality of marital life, and the sustainability of marriage. Faith, prayer, mysticism, Divine attachment, faithful commitment, spiritual chastity, and other forms of religiosity and spiritual inclination strengthen and enhance the quality of marital relationships and seem to shield the marriage from EMI (2).

It encourages ethical behaviors such as fairness to the spouse, internal or external adherence to family foundations, and strengthening of self-control as deterrents to infidelity. Participating in religious ceremonies, along with self-awareness and a religious mindset, are potential contributing factors in controlling negative behavioral tendencies (56). People’s attitude towards EMI is an important indicator in predicting their desire and tendency to engage in these relationships. Religious and spiritual beliefs and values can encourage or prohibit involvement in EMI. People who are lax in their beliefs are more likely to be involved in EMI (28).

4. Treatment Framework

4.1. Extramarital Infidelity Therapy Based on A Spiritual Attitude

Couples’ religious beliefs and practices help them have marital commitment (57). The mental health of couples depends on their attitude towards the world, their spouse, their family, and their own duties and perceived needs. In other words, people with religious backgrounds have higher marital commitment and a lower tendency to be involved in EMI (2, 58, 59).

What strengthens marital life is sound ethics, piety, kindness, chastity, good fellowship, mutual respect, forgiveness, tolerance, and loving words. Accordingly, therapists are encouraged to non-judgmentally explore spiritual issues associated with improving and restoring the client’s mental health (58) to increase marital satisfaction and well-being and reduce the couple’s anxiety and conflict (60-62).

Religiosity is negatively associated with harmful behaviors such as heavy abuse of alcohol and other substances, risky or illegal sexual activity, and committing a crime (56). Adherence to church and spiritual beliefs is associated with a lower probability of marital infidelity (63). Marital infidelity is predicted by high neuroticism and low religiosity (64). Being religious significantly causes one to view flirtatious conversations as sexual infidelity (65).

Spiritual well-being in the family can be effective in preventing many problems in the family environment, including conflicts, disagreements, and dissatisfaction, all of which are risk factors of EMI. Spiritual health plays an important role in improving the quality of interpersonal relationships in different social contexts and giving meaning to life (66). Note that conversations about spirituality with clients should be made in a non-judgmental, respectful atmosphere full of compassion (67).

4.2 Extramarital Infidelity Therapy Based on Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions

Cognitive behavioral therapy, as a skill-based approach, helps people enhance their cognitive, problem-solving, conflict resolution, and communication skills and learn the principles of proper behavior to bring about change in marital life. It encourages them to reconsider their interpretations of events in marital life and brings about purposeful behavior, the appropriate expression of inner emotions, a better understanding of individual differences, the revision of sexual performance, the criticism of personal behavior, and the creation of intimacy (68).

Destructive relationships occur when people have irrational beliefs about themselves, their spouses, and their relationships. When marital life is not in line with their irrational expectations, negative evaluations and tendencies are produced, causing them to experience intense negative emotions and leading them to behave negatively towards their spouse. Cognitive behavioral therapy challenges their false beliefs, guides them to find and replace irrational ideas, and makes them confront their involuntary thoughts (23).

It helps individuals achieve a different perspective on their marital problems by changing their thinking process, combating negative feelings, replacing them with positive and rational thoughts, and enabling them to communicate better with their spouses (23). These factors reduce the predisposing factors of EMI.

5. Summary

Spirituality can have a positive effect on the behavior of women, marital life, and cultural and social conditions and can thus prevent situations that may lead to EMI. Extramarital infidelity involves unethical behaviors through which people reveal the problematic or psychologically harmed or abused aspects of their own personality without committing an obvious criminal offense (54). Despite the prevalence of these relationships in the community, there are few therapeutic approaches in experimental research that have proven effective in dealing with it; most therapists describe this as a big lack of evidence-based approaches to EMI (66), including interaction analysis, narrative-focused and couple-based therapies, reality therapy, and other cognitive-behavioral interventions (23, 25, 55, 60-62, 66).

Of course, we know no therapeutic approach is effective for all clients and all problems, and given some limitations in each of these approaches, various studies have shown that eclectic or integrative approaches can provide a better point of view for addressing patient-specific problems. Additionally, this issue is more prominent in EMI, which is a complex psycho-socio-spiritual event. It is important to select a way to detect the disturbed mechanisms of self-control and avoidance that lead people to infidelity to improve therapeutic efficacy and efficiency (55).

Cognitive-behavioral techniques help individuals achieve a different perspective on their problems and improve their communication with their spouses by changing their thinking processes and replacing cognitive distortions with rational thoughts (23). Spirituality helps clients confront their problems and change and grow as a result (69). Spirituality is an aspect of human life, and when those who engage in such relationships go into therapy, they do not leave their spiritual dimension behind but bring along their spiritual beliefs, practices, experiences, values, relationships, and spiritual challenges into the sessions (70, 71). Also, a similar review study showed that spiritually-based interventions are often effective. In addition, some clients tend to have their therapist use spiritual therapy in sessions. For many religious/spiritual clients, this can be done by both religious and secular therapists. Therefore, therapists must also address the client’s concerns regarding spirituality (72).

Spirituality is a significant element of human life that can influence thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. The spiritual dimension is considered foundational to all other dimensions of human experience and is in a holistic relationship with them. Using a CBT approach during therapy with religious/spiritual clients can be beneficial as it focuses on core beliefs and assumptions, emphasizes education, and is often viewed favorably by religious clients. Spiritually-oriented CBT has strengths such as providing social support, building Divine coping resources, and increasing spiritual motivation. However, it also has weaknesses, such as belief imposition and the possibility of offending or straining the client. It is important to consider these strengths and weaknesses when implementing spiritually oriented-CBT to ensure effective therapy (49).

Given that EMI is a social and familial taboo, research in this area is particularly problematic. A low level of disclosure is common among those who have experienced EMI and those who have committed EMI themselves. Application of the spiritual realm as an aid for coping with the desire for unethical sexual relationships, reinforced by cognitive-behavioral techniques, maybe a suitable method to approach this complicated phenomenon.

Creating a range of spiritually-focused therapy techniques, structured programs, and applications that consider the religious and spiritual specificities of Iran is crucial. It is also important for psychological counselors working in this field to participate in training programs on religious/spiritual counseling skills in addition to their general therapy education. This will enable them to provide effective therapy that considers the spiritual and religious aspects of their client’s lives and provides a more holistic approach to treatment.

.jpeg)